The Case of Rose Bird: Gender, Politics, and the California Courts / Kathleen A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CSCHS News Spring/Summer 2015

California Supreme Court Historical Society newsletter · s p r i n g / summer 2015 Righting a WRong After 125 Years, Hong Yen Chang Becomes a California Lawyer Righting a Historic Wrong The Posthumous Admission of Hong Yen Chang to the California Bar By Jeffrey L. Bleich, Benjamin J. Horwich and Joshua S. Meltzer* n March 16, 2015, the 2–1 decision, the New York Supreme California Supreme Court Court rejected his application on Ounanimously granted Hong the ground that he was not a citi- Yen Chang posthumous admission to zen. Undeterred, Chang continued the State Bar of California. In its rul- to pursue admission to the bar. In ing, the court repudiated its 125-year- 1887, a New York judge issued him old decision denying Chang admission a naturalization certificate, and the based on a combination of state and state legislature enacted a law per- federal laws that made people of Chi- mitting him to reapply to the bar. The nese ancestry ineligible for admission New York Times reported that when to the bar. Chang’s story is a reminder Chang and a successful African- of the discrimination people of Chi- American applicant “were called to nese descent faced throughout much sign for their parchments, the other of this state’s history, and the Supreme students applauded each enthusiasti- Court’s powerful opinion explaining cally.” Chang became the only regu- why it granted Chang admission is Hong Yen Chang larly admitted Chinese lawyer in the an opportunity to reflect both on our United States. state and country’s history of discrimination and on the Later Chang applied for admission to the Califor- progress that has been made. -

Becoming Chief Justice: the Nomination and Confirmation Of

Becoming Chief Justice: A Personal Memoir of the Confirmation and Transition Processes in the Nomination of Rose Elizabeth Bird BY ROBERT VANDERET n February 12, 1977, Governor Jerry Brown Santa Clara County Public Defender’s Office. It was an announced his intention to nominate Rose exciting opportunity: I would get to assist in the trials of OElizabeth Bird, his 40-year-old Agriculture & criminal defendants as a bar-certified law student work- Services Agency secretary, to be the next Chief Justice ing under the supervision of a public defender, write of California, replacing the retiring Donald Wright. The motions to suppress evidence and dismiss complaints, news did not come as a surprise to me. A few days earlier, and interview clients in jail. A few weeks after my job I had received a telephone call from Secretary Bird asking began, I was assigned to work exclusively with Deputy if I would consider taking a leave of absence from my posi- Public Defender Rose Bird, widely considered to be the tion as an associate at the Los Angeles law firm, O’Mel- most talented advocate in the office. She was a welcom- veny & Myers, to help manage her confirmation process. ing and supportive supervisor. That confirmation was far from a sure thing. Although Each morning that summer, we would meet at her it was anticipated that she would receive a positive vote house in Palo Alto and drive the short distance to the from Associate Justice Mathew Tobriner, who would San Jose Civic Center in Rose’s car, joined by my co-clerk chair the three-member for the summer, Dick Neuhoff. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

Publication and Depublication of California Court of Appeal Opinions: Is the Eraser Mightier Than the Pencil? Gerald F

Santa Clara Law Santa Clara Law Digital Commons Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 1-1-1992 Publication and Depublication of California Court of Appeal Opinions: Is the Eraser Mightier than the Pencil? Gerald F. Uelmen Santa Clara University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/facpubs Recommended Citation 26 Loy. L. A. L. Rev. 1007 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PUBLICATION AND DEPUBLICATION OF CALIFORNIA COURT OF APPEAL OPINIONS: IS THE ERASER MIGHTIER THAN THE PENCIL? Gerald F. Uelmen* What is a modem poet's fate? To write his thoughts upon a slate; The critic spits on what is done, Gives it a wipe-and all is gone.' I. INTRODUCTION During the first five years of the Lucas court,2 the California Supreme Court depublished3 586 opinions of the California Court of Ap- peal, declaring what the law of California was not.4 During the same five-year period, the California Supreme Court published a total of 555 of * Dean and Professor of Law, Santa Clara University School of Law. B.A., 1962, Loyola Marymount University; J.D., 1965, LL.M., 1966, Georgetown University Law Center. The author would like to acknowledge the assistance of Patrick Martucci, J.D., 1993, Santa Clara University School of Law, in the research for this Article. -

2019 Guide to the Wisconsin Supreme Court and Judicial Evaluation Fourth Edition: 2018-19 Term

2019 Guide to the Wisconsin Supreme Court and Judicial Evaluation Fourth Edition: 2018-19 Term November 2019 2019 GUIDE TO THE WISCONSIN SUPREME COURT AND JUDICIAL EVALUATION Prepared By: Paige Scobee, Hamilton Consulting Group, LLC November 2019 The Wisconsin Civil Justice Council, Inc. (WCJC) was formed in 2009 to represent Wisconsin business inter- ests on civil litigation issues before the legislature and courts. WCJC’s mission is to promote fairness and equi- ty in Wisconsin’s civil justice system, with the ultimate goal of making Wisconsin a better place to work and live. The WCJC board is proud to present its fourth Guide to the Wisconsin Supreme Court and Judicial Evalua- tion. The purpose of this publication is to educate WCJC’s board members and the public about the role of the Supreme Court in Wisconsin’s business climate by providing a summary of the most important decisions is- sued by the Wisconsin Supreme Court affecting the Wisconsin business community. Board Members Bill G. Smith Jason Culotta Neal Kedzie National Federation of Independent Midwest Food Products Wisconsin Motor Carriers Business, Wisconsin Chapter Association Association Scott Manley William Sepic Matthew Hauser Wisconsin Manufacturers & Wisconsin Automobile & Truck Wisconsin Petroleum Marketers & Commerce Dealers Association Convenience Store Association Andrew Franken John Holevoet Kristine Hillmer Wisconsin Insurance Alliance Wisconsin Dairy Business Wisconsin Restaurant Association Association Brad Boycks Wisconsin Builders Association Brian Doudna Wisconsin Economic Development John Mielke Association Associated Builders & Contractors Eric Borgerding Gary Manke Wisconsin Hospital Association Midwest Equipment Dealers Association 10 East Doty Street · Suite 500 · Madison, WI 53703 www.wisciviljusticecouncil.org · 608-258-9506 WCJC 2019 Guide to the Wisconsin Supreme Court Page 2 and Judicial Evaluation Executive Summary The Wisconsin Supreme Court issues decisions that have a direct effect on Wisconsin businesses and individu- als. -

Hastings Law News Vol.18 No.2 UC Hastings College of the Law

University of California, Hastings College of the Law UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Hastings Law News UC Hastings Archives and History 11-1-1984 Hastings Law News Vol.18 No.2 UC Hastings College of the Law Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/hln Recommended Citation UC Hastings College of the Law, "Hastings Law News Vol.18 No.2" (1984). Hastings Law News. Book 132. http://repository.uchastings.edu/hln/132 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the UC Hastings Archives and History at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Law News by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hastings College of the Law Nov. Dec. 1984 SUPREME COURT'S SEVEN DEADLY SINS "To construe and build the law - especially constitutional law - is 4. Inviting the tyranny of small decisions: When the Court looks at a prior decision to choose the kind of people we will be," Laurence H. Tribe told a and decides it is only going a little step further a!ld therefore doing no harm, it is look- ing at its feet to see how far it has gone. These small steps sometimes reduce people to standing-room-only audience at Hastings on October 18, 1984. Pro- things. fessor Tribe, Tyler Professor of Constitutional Law at Harvard, gave 5. Ol'erlooking the constitutil'e dimension 0/ gOl'ernmental actions and what they the 1984 Mathew O. Tobriner Memorial Lecture on the topic of "The sa)' about lIS as a people and a nation: Constitutional decisions alter the scale of what Court as Calculator: the Budgeting of Rights." we constitute, and the Court should not ignore this element. -

IRA MARK ELLMAN Professor and Willard H. Pedrick Distinguished Research Scholar Sandra Day O'connor College of Law Arizona

IRA MARK ELLMAN Professor and Willard H. Pedrick Distinguished Research Scholar Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law Arizona State University Tempe, Arizona 85287-7906 (480) 965-2125 http://www.law.asu.edu/HomePages/Ellman/ EDUCATION: J.D. Boalt Hall School of Law, University of California, Berkeley (June, 1973). Head Article Editor, California Law Review. Order of the Coif. M.A. Psychology, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois (October, 1969). National Institute of Mental Health Fellowship. B.A. Psychology, Reed College, Portland, Oregon (May, 1967). Nominated, Woodrow Wilson Fellowship. JUDICIAL CLERKSHIPS: Associate Justice William O. Douglas United States Supreme Court, 1973-74. Associate Justice Mathew Tobriner, California Supreme Court, 1/31/72 through 6/5/72. PERMANENT AND VISITING AFFILIATIONS: 5/81 to Present: Professor of Law and (since 2001) Willard H. Pedrick Distinguished Research Scholar, Arizona State University. 9/2003 to Present Affiliate Faculty Member, Center for Child and Youth Policy, University of California at Berkeley. 9/2010 to 12/2010 Visiting Fellow Commoner, Trinity College, University of Cambridge 6/2007 to 12/2007 Visiting Scholar, Center for the Study of Law and Society, U.C. Berkeley 8/2006 to 12/2006 Visiting Professor of Law, Brooklyn Law School 10/95 to 5/2001 Chief Reporter, American Law Institute, for Principles of the Law of Family Dissolution. Justice R. Ammi Cutter Reporter, from June, 1998. (Reporter, 10/92-10/95; Associate Reporter, 2/91 to 10/92). 8/2005 to 12/2005 Visiting Scholar, School of Social Welfare, University of California, Berkeley 8/2004 to 12/2004 Visiting Scholar, Center for Law and Society, University of California, Berkeley 8/2003 to 12/2003 Visiting Scholar, Center for Law and Society, University of California, Berkeley 8/2000 to 5/2002 Visiting Professor, Hastings College of The Law, University of California. -

How Do Judges Decide School Finance Cases?

HOW DO JUDGES DETERMINE EDUCATIONAL RIGHTS? Ethan Hutt,* Daniel Klasik,† & Aaron Tang‡ ABSTRACT There is an old riddle that asks, what do constitutional school funding lawsuits and birds have in common? The answer: every state has its own. Yet while almost every state has experienced hotly-contested school funding litigation, the results of these suits have been nearly impossible to predict. Scholars and advocates have struggled for decades to explain why some state courts rule for plaintiff school children—often resulting in billions of dollars in additional school spending—while others do not. If there is rough agreement on anything, it is that “the law” is not the answer: variation in the strength of state constitutional education clauses is uncorrelated with the odds of plaintiff success. Just what factors do explain different outcomes, though, is anybody’s guess. One researcher captured the academy’s state of frustration aptly when she suggested that whether a state’s school funding system will be invalidated “depends almost solely on the whimsy of the state supreme court justices themselves.” In this Article, we analyze an original data set of 313 state-level school funding decisions using multiple regression models. Our findings confirm that the relative strength of a state’s constitutional text regarding education has no bearing on school funding lawsuit outcomes. But we also reject the judicial whimsy hypothesis. Several variables— including the health of the national economy (as measured by GDP growth), Republican control over the state legislature, and an appointment-based mechanism of judicial selection—are significantly and positively correlated with the odds of a school funding system being declared unconstitutional. -

Famous Cases of the Wisconsin Supreme Court

In Re: Booth 3 Wis. 1 (1854) What has become known as the Booth case is actually a series of decisions from the Wisconsin Supreme Court beginning in 1854 and one from the U.S. Supreme Court, Ableman v. Booth, 62 U.S. 514 (1859), leading to a final published decision by the Wisconsin Supreme Court in Ableman v. Booth, 11 Wis. 501 (1859). These decisions reflect Wisconsin’s attempted nullification of the federal fugitive slave law, the expansion of the state’s rights movement and Wisconsin’s defiance of federal judicial authority. The Wisconsin Supreme Court in Booth unanimously declared the Fugitive Slave Act (which required northern states to return runaway slaves to their masters) unconstitutional. The U.S. Supreme Court overturned that decision but the Wisconsin Supreme Court refused to file the U.S. Court’s mandate upholding the fugitive slave law. That mandate has never been filed. When the U.S. Constitution was drafted, slavery existed in this country. Article IV, Section 2 provided as follows: No person held to service or labor in one state under the laws thereof, escaping into another, shall in consequence of any law or regulation therein, be discharged from such service or labor, but shall be delivered up on claim of the party to whom such service or labor may be due. Based on this provision, Congress in 1793 passed a law that permitted the owner of any runaway slave to arrest him, take him before a judge of either the federal or state courts and prove by oral testimony or by affidavit that the person arrested owed service to the claimant under the laws of the state from which he had escaped; if the judge found the evidence to be sufficient, the slave owner could bring the fugitive back to the state from which he had escaped. -

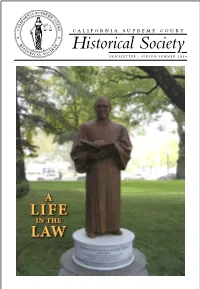

Highlights from a New Biography of Justice Stanley Mosk by Jacqueline R

California Supreme Court Historical Society newsletter · s p r i n g / summer 2014 A Life in The LAw The Longest-Serving Justice Highlights from a New Biography of Justice Stanley Mosk By Jacqueline R. Braitman and Gerald F. Uelmen* undreds of mourners came to Los Angeles’ future allies. With rare exceptions, Mosk maintained majestic Wilshire Boulevard Temple in June of cordial relations with political opponents throughout H2001. The massive, Byzantine-style structure his lengthy career. and its hundred-foot-wide dome tower over the bustling On one of his final days in office, Olson called Mosk mid-city corridor leading to the downtown hub of finan- into his office and told him to prepare commissions to cial and corporate skyscrapers. Built in 1929, the historic appoint Harold Jeffries, Harold Landreth, and Dwight synagogue symbolizes the burgeoning pre–Depression Stephenson to the Superior Court, and Eugene Fay and prominence and wealth of the region’s Mosk himself to the Municipal Court. Jewish Reform congregants, includ- Mosk thanked the governor profusely. ing Hollywood moguls and business The commissions were prepared and leaders. Filing into the rows of seats in the governor signed them, but by then the cavernous sanctuary were two gen- it was too late to file them. The secre- erations of movers and shakers of post- tary of state’s office was closed, so Mosk World War II California politics, who locked the commissions in his desk and helped to shape the course of history. went home, intending to file them early Sitting among less recognizable faces the next morning. -

The California Recall History Is a Chronological Listing of Every

Complete List of Recall Attempts This is a chronological listing of every attempted recall of an elected state official in California. For the purposes of this history, a recall attempt is defined as a Notice of Intention to recall an official that is filed with the Secretary of State’s Office. 1913 Senator Marshall Black, 28th Senate District (Santa Clara County) Qualified for the ballot, recall succeeded Vote percentages not available Herbert C. Jones elected successor Senator Edwin E. Grant, 19th Senate District (San Francisco County) Failed to qualify for the ballot 1914 Senator Edwin E. Grant, 19th Senate District (San Francisco County) Qualified for the ballot, recall succeeded Vote percentages not available Edwin I. Wolfe elected successor Senator James C. Owens, 9th Senate District (Marin and Contra Costa counties) Qualified for the ballot, officer retained 1916 Assemblyman Frank Finley Merriam Failed to qualify for the ballot 1939 Governor Culbert L. Olson Failed to qualify for the ballot Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Citizens Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot 1940 Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot 1960 Governor Edmund G. Brown Filed by Roderick J. Wilson Failed to qualify for the ballot 1 Complete List of Recall Attempts 1965 Assemblyman William F. Stanton, 25th Assembly District (Santa Clara County) Filed by Jerome J. Ducote Failed to qualify for the ballot Assemblyman John Burton, 20th Assembly District (San Francisco County) Filed by John Carney Failed to qualify for the ballot Assemblyman Willie L. -

Notes on Alums Jack Auhk ('581 Was Elected to the Bench Atlanta Firm of Hurt, Richardson, Garner, in Branch 4 of the Dane County, Wis., Todd & Cadenhead

15 Notes on Alums Jack AuHk ('581 was elected to the bench Atlanta firm of Hurt, Richardson, Garner, in Branch 4 of the Dane County, Wis., Todd & Cadenhead. Mr. Thrcott recently Circuit Court in April, and assumed his completed a tour of duty with the US new position in August. Aulik has prac- Marine Corps. ticed law and lived in Sun Prairie Paul ], Fisher ('60) has been since 1959. appointed General Counsel for Ariston Steven W. Weinke ('661was recently Capital Management and California elected Circuit Court Judge for Fond du Divisional Manager. Lac County, Wis. Weinke succeeds US District Judge John Reynolds Eugene F. McEssey ('491, who served the ('491, a member of the Law School's county for 24 years. Board of Visitors, has announced that he Pat Richter ('71) has been named will take senior status in the Eastern Dis- director of personnel for Oscar Mayer trict of Wisconsin. Judge Reynolds had Foods Corp., Madison. Richter was per- also served as Wisconsin Attorney sonnel manager for the beverages divi- General and Governor. sion of General Foods, White Plains, N.Y. David W. Wood ('81) has joined the Alan R. Post ('72) has become an Columbus, Ohio firm of Vorys, Sater, associate with the firm Sorling, Northrup, Seymour and Pease. Hanna, Cullen and Cochran, Ltd., Spring- Scott Jennings ('75) has been named field, Ill. Post had been with Illinois Bell, an Associate Editor of the Lawyers Coop- Chicago. erative Publishing Co., Rochester, NY. James H. Haberstroh ('751 became a For the past seven years, Mr. Jennings vice president of First Wisconsin Trust was with the US Department of Energy Co., Milwaukee.