AVAILABLE from a Teacher's Notebook: Mathematics, K-9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE GEOMETRY of PYRAMIDS One of the More Interesting Solid

THE GEOMETRY OF PYRAMIDS One of the more interesting solid structures which has fascinated individuals for thousands of years going all the way back to the ancient Egyptians is the pyramid. It is a structure in which one takes a closed curve in the x-y plane and connects straight lines between every point on this curve and a fixed point P above the centroid of the curve. Classical pyramids such as the structures at Giza have square bases and lateral sides close in form to equilateral triangles. When the closed curve becomes a circle one obtains a cone and this cone becomes a cylindrical rod when point P is moved to infinity. It is our purpose here to discuss the properties of all N sided pyramids including their volume and surface area using only elementary calculus and geometry. Our starting point will be the following sketch- The base represents a regular N sided polygon with side length ‘a’ . The angle between neighboring radial lines r (shown in red) connecting the polygon vertices with its centroid is θ=2π/N. From this it follows, by the law of cosines, that the length r=a/sqrt[2(1- cos(θ))] . The area of the iscosolis triangle of sides r-a-r is- a a 2 a 2 1 cos( ) A r 2 T 2 4 4 (1 cos( ) From this we have that the area of the N sided polygon and hence the pyramid base will be- 2 2 1 cos( ) Na A N base 2 4 1 cos( ) N 2 It readily follows from this result that a square base N=4 has area Abase=a and a hexagon 2 base N=6 yields Abase= 3sqrt(3)a /2. -

Lateral and Surface Area of Right Prisms 1 Jorge Is Trying to Wrap a Present That Is in a Box Shaped As a Right Prism

CHAPTER 11 You will need Lateral and Surface • a ruler A • a calculator Area of Right Prisms c GOAL Calculate lateral area and surface area of right prisms. Learn about the Math A prism is a polyhedron (solid whose faces are polygons) whose bases are congruent and parallel. When trying to identify a right prism, ask yourself if this solid could have right prism been created by placing many congruent sheets of paper on prism that has bases aligned one above the top of each other. If so, this is a right prism. Some examples other and has lateral of right prisms are shown below. faces that are rectangles Triangular prism Rectangular prism The surface area of a right prism can be calculated using the following formula: SA 5 2B 1 hP, where B is the area of the base, h is the height of the prism, and P is the perimeter of the base. The lateral area of a figure is the area of the non-base faces lateral area only. When a prism has its bases facing up and down, the area of the non-base faces of a figure lateral area is the area of the vertical faces. (For a rectangular prism, any pair of opposite faces can be bases.) The lateral area of a right prism can be calculated by multiplying the perimeter of the base by the height of the prism. This is summarized by the formula: LA 5 hP. Copyright © 2009 by Nelson Education Ltd. Reproduction permitted for classrooms 11A Lateral and Surface Area of Right Prisms 1 Jorge is trying to wrap a present that is in a box shaped as a right prism. -

Pentagonal Pyramid

Chapter 9 Surfaces and Solids Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. Pyramids, Area, and 9.2 Volume Copyright © Cengage Learning. All rights reserved. Pyramids, Area, and Volume The solids (space figures) shown in Figure 9.14 below are pyramids. In Figure 9.14(a), point A is noncoplanar with square base BCDE. In Figure 9.14(b), F is noncoplanar with its base, GHJ. (a) (b) Figure 9.14 3 Pyramids, Area, and Volume In each space pyramid, the noncoplanar point is joined to each vertex as well as each point of the base. A solid pyramid results when the noncoplanar point is joined both to points on the polygon as well as to points in its interior. Point A is known as the vertex or apex of the square pyramid; likewise, point F is the vertex or apex of the triangular pyramid. The pyramid of Figure 9.14(b) has four triangular faces; for this reason, it is called a tetrahedron. 4 Pyramids, Area, and Volume The pyramid in Figure 9.15 is a pentagonal pyramid. It has vertex K, pentagon LMNPQ for its base, and lateral edges and Although K is called the vertex of the pyramid, there are actually six vertices: K, L, M, N, P, and Q. Figure 9.15 The sides of the base and are base edges. 5 Pyramids, Area, and Volume All lateral faces of a pyramid are triangles; KLM is one of the five lateral faces of the pentagonal pyramid. Including base LMNPQ, this pyramid has a total of six faces. The altitude of the pyramid, of length h, is the line segment from the vertex K perpendicular to the plane of the base. -

Module-03 / Lecture-01 SOLIDS Introduction- This Chapter Deals with the Orthographic Projections of Three – Dimensional Objects Called Solids

1 Module-03 / Lecture-01 SOLIDS Introduction- This chapter deals with the orthographic projections of three – dimensional objects called solids. However, only those solids are considered the shape of which can be defined geometrically and are regular in nature. To understand and remember various solids in this subject properly, those are classified & arranged in to two major groups- Polyhedron- A polyhedron is defined as a solid bounded by planes called faces, which meet in straight lines called edges. Regular Polyhedron- It is polyhedron, having all the faces equal and regular. Tetrahedron- It is a solid, having four equal equilateral triangular faces. Cube- It is a solid, having six equal square faces. Octahedron- It is a solid, having eight equal equilateral triangular faces. Dodecahedron- It is a solid, having twelve equal pentagonal faces. Icosahedrons- It is a solid, having twenty equal equilateral triangular faces. Prism- This is a polyhedron, having two equal and similar regular polygons called its ends or bases, parallel to each other and joined by other faces which are rectangles. The imaginary line joining the centre of the bases is called the axis. A right and regular prism has its axis perpendicular to the base. All the faces are equal rectangles. 1 2 Pyramid- This is a polyhedron, having a regular polygon as a base and a number of triangular faces meeting at a point called the vertex or apex. The imaginary line joining the apex with the centre of the base is known as the axis. A right and regular pyramid has its axis perpendicular to the base which is a regular plane. -

Apollonius of Pergaconics. Books One - Seven

APOLLONIUS OF PERGACONICS. BOOKS ONE - SEVEN INTRODUCTION A. Apollonius at Perga Apollonius was born at Perga (Περγα) on the Southern coast of Asia Mi- nor, near the modern Turkish city of Bursa. Little is known about his life before he arrived in Alexandria, where he studied. Certain information about Apollonius’ life in Asia Minor can be obtained from his preface to Book 2 of Conics. The name “Apollonius”(Apollonius) means “devoted to Apollo”, similarly to “Artemius” or “Demetrius” meaning “devoted to Artemis or Demeter”. In the mentioned preface Apollonius writes to Eudemus of Pergamum that he sends him one of the books of Conics via his son also named Apollonius. The coincidence shows that this name was traditional in the family, and in all prob- ability Apollonius’ ancestors were priests of Apollo. Asia Minor during many centuries was for Indo-European tribes a bridge to Europe from their pre-fatherland south of the Caspian Sea. The Indo-European nation living in Asia Minor in 2nd and the beginning of the 1st millennia B.C. was usually called Hittites. Hittites are mentioned in the Bible and in Egyptian papyri. A military leader serving under the Biblical king David was the Hittite Uriah. His wife Bath- sheba, after his death, became the wife of king David and the mother of king Solomon. Hittites had a cuneiform writing analogous to the Babylonian one and hi- eroglyphs analogous to Egyptian ones. The Czech historian Bedrich Hrozny (1879-1952) who has deciphered Hittite cuneiform writing had established that the Hittite language belonged to the Western group of Indo-European languages [Hro]. -

Triangulations and Simplex Tilings of Polyhedra

Triangulations and Simplex Tilings of Polyhedra by Braxton Carrigan A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama August 4, 2012 Keywords: triangulation, tiling, tetrahedralization Copyright 2012 by Braxton Carrigan Approved by Andras Bezdek, Chair, Professor of Mathematics Krystyna Kuperberg, Professor of Mathematics Wlodzimierz Kuperberg, Professor of Mathematics Chris Rodger, Don Logan Endowed Chair of Mathematics Abstract This dissertation summarizes my research in the area of Discrete Geometry. The par- ticular problems of Discrete Geometry discussed in this dissertation are concerned with partitioning three dimensional polyhedra into tetrahedra. The most widely used partition of a polyhedra is triangulation, where a polyhedron is broken into a set of convex polyhedra all with four vertices, called tetrahedra, joined together in a face-to-face manner. If one does not require that the tetrahedra to meet along common faces, then we say that the partition is a tiling. Many of the algorithmic implementations in the field of Computational Geometry are dependent on the results of triangulation. For example computing the volume of a polyhedron is done by adding volumes of tetrahedra of a triangulation. In Chapter 2 we will provide a brief history of triangulation and present a number of known non-triangulable polyhedra. In this dissertation we will particularly address non-triangulable polyhedra. Our research was motivated by a recent paper of J. Rambau [20], who showed that a nonconvex twisted prisms cannot be triangulated. As in algebra when proving a number is not divisible by 2012 one may show it is not divisible by 2, we will revisit Rambau's results and show a new shorter proof that the twisted prism is non-triangulable by proving it is non-tilable. -

SOLID GEOMETRY CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Eon^On: FETTER LANE, E.G

QA UC-NRLF 457 ^B 557 i35 ^ Ml I 9^^ soLiTf (itlOMK'l'RV BY C. GODFREY, HEAD M STER CF THE ROY I ^1 f i ! i-ORMERI.Y ; EN ;R MAI :: \: i^;. ; \MNCHEST1-R C(.1J,E(;E an:; \\\ A. SIDDON , MA :^1AN r MASTER .AT ..\:--:: : ', l-ELLi)V* i OF JESL'S COI.' E, CAMf. ^'ambridge : at tlie 'Jniversity Press 191 1 IN MEMORIAM FLORIAN CAJORI Q^^/ff^y^-^ SOLID GEOMETRY CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Eon^on: FETTER LANE, E.G. C. F. CLAY, Manager (fFtjinfturgi) : loo, PRINCES STREET iSerlin: A. ASHER AND CO. ILjipjig: F. A. BROCKHAUS ^tia lork: G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS iSombas anU Calcutta: MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd. A /I rights resei'ved SOLID GEOMETRY BY C. GODFREY, M.V.O. ; M.A. w HEAD MASTER OF THE ROYAL NAVAL COLLEGE, OSBORNE FORMERLY SENIOR MATHEMATICAL MASTER AT WINCHESTER COLLEGE AND A. W. SIDDONS, M.A. ASSISTANT MASTER AT HARROW SCHOOL LATE FELLOW OF JESUS COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE Cambridge : at the University Press 191 1 Camfariljge: PRINTED BY JOHN CLAY, M.A. AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS. CAJORl PREFACE "It is a great defect in most school courses of geometry " that they are entirely confined to two dimensions. Even *' if solid geometry in the usual sense is not attempted, every ''occasion should be taken to liberate boys' minds from "what becomes the tyranny of paper But beyond this "it should be possible, if the earlier stages of the plane "geometry work are rapidly and effectively dealt with as "here suggested, to find time for a short course of solid " geometry. -

Properties of Quadrilaterals If a Quadrilateral Is a

Properties of Quadrilaterals If a quadrilateral is a .... Parallelogram Rhombus Kite Isosceles Rectangle Square Trapezoid Then... Opposite sides are Opposite sides are Opposite sides are Opposite sides are parallel Two disjoint pairs of The legs are congruent. parallel parallel parallel consecutive sides are All sides are congruent. congruent. The bases are parallel. Opposite sides are Opposite sides are All sides are congruent. congruent congruent All angles are right angles. The diagonals are The lower base angles Opposite angles are perpendicular are congruent. Opposite angles are Diagonals bisect each congruent. Diagonals bisect each other. congruent. other One diagonal is the The upper base angles Diagonals bisect each The diagonals are perpendicular bisector of are congruent. Diagonals bisect each Any pair of consecutive other. perpendicular. the other. other angles are The diagonals are supplementary Any pair of consecutive The diagonals bisect the One of the diagonals congruent Any pair of consecutive . angles are angles of the square. bisects a pair of opposite angles are All angles are right supplementary. angles. Any lower base angle is supplementary. angles. Any pair of consecutive supplementary to any The diagonals are angles are supplementary. One pair of opposite upper base angle. The diagonals are perpendicular. angles are congruent. congruent. The diagonals are The diagonals bisect the congruent. angles of the rhombus. The diagonals divide the The diagonals divide the square into four congruent rhombus into four isosceles right triangles. congruent right triangles. . -

Geometry for Drafting Section 5.1 Applied Geometry for Board Drafting Section 5.2 Applied Geometry for CAD Systems

5 Geometry for Drafting Section 5.1 Applied Geometry for Board Drafting Section 5.2 Applied Geometry for CAD Systems Chapter Objectives • Identify geometric shapes and construc- tions used by drafters. • Construct various geometric shapes. • Solve technical and mathematical prob- lems through geomet- ric constructions using drafting instruments. • Solve technical and mathematical prob- lems through geomet- ric constructions using a CAD system. • Use geometry to reduce or enlarge a drawing or to change its proportions. Defying Convention It has been said that Zaha Hadid has built a career on defying convention—conventional ideas of architectural space, and of construction. What do you see in the building shown here that defi es convention? 132 Drafting Career Zaha Hadid, Architect Architect Zaha Hadid’s designs for the Cincinnati Contemporary Art Center were “like a rollercoaster, a little scary, but exhilarating,” says Center direc- tor Charles Desmarais. Critics said “she was a paper architect, someone who had great respect as a theo- rist and as a thinker about architecture but who hadn't had the opportunity to build.” “She totally got what we were trying to do,” said Desmarais, “which was to try and bridge that sort of gap between the inside and the outside, between the world and the museum.” She certainly did. Zaha Hadid is the fi rst woman in the world to design a museum and to win the prestigious Pritzker Architec- ture Prize. Academic Skills and Abilities • Math • Computer sciences • Business management skills • Verbal and written communication skills • Organizing and planning skills Career Pathways There is a wealth of opportunities outside the classroom for expanding your drafting knowledge. -

Find the Volume of Each Prism. 1. SOLUTION

12-4 Volumes of Prisms and Cylinders Find the volume of each prism. 1. SOLUTION: The volume V of a prism is V = Bh, where B is the area of a base and h is the height of the prism. 3 The volume is 108 cm . ANSWER: 108 cm3 2. SOLUTION: The volume V of a prism is V = Bh, where B is the area of a base and h is the height of the prism. ANSWER: 3 396 in 3. the oblique rectangular prism shown at the right eSolutions Manual - Powered by Cognero Page 1 SOLUTION: If two solids have the same height h and the same cross-sectional area B at every level, then they have the same volume. So, the volume of a right prism and an oblique one of the same height and cross sectional area are same. ANSWER: 26.95 m3 4. an oblique pentagonal prism with a base area of 42 square centimeters and a height of 5.2 centimeters SOLUTION: If two solids have the same height h and the same cross-sectional area B at every level, then they have the same volume. So, the volume of a right prism and an oblique one of the same height and cross sectional area are same. ANSWER: 3 218.4 cm Find the volume of each cylinder. Round to the nearest tenth. 5. SOLUTION: ANSWER: 206.4 ft3 6. SOLUTION: If two solids have the same height h and the same cross-sectional area B at every level, then they have the same volume. -

Askdrcallahan Algebra I Teacher's Guide

AskDrCallahan Algebra I Teacher’s Guide 5th Edition rev09072012 Cassidy G. Callahan, Instructor Dale Callahan, Ph.D., P.E. Lea Callahan, MSEE, P.E. Copyright © 2012 AskDrCallahan, LLC v5-r09072012 2 Welcome to AskDrCallahan Algebra 1 Start Here! 1. Make sure you have all of the following. • Elementary Algebra, by Harold R. Jacobs. ISBN: 0716710471 • Solutions Manual for Elementary Algebra. ISBN: 0615315011 • Scientific calculator (TI-30 style or better)** • DVD set of five (5) DVDs * 2. Course Introduction. Both the teacher and the student should put in the first DVD and play the course introduction. Watch this section together. 3. Review the syllabus. If you are new to using a syllabus, we have posted a Syllabus Tutorial on our website to help you navigate the syllabus format. You may also contact Homework Help for support. The syllabus is essentially an outline of pace and sequence for the course. The syllabus is also the place where we assign the homework problems for your student. Many parents find it useful to make a copy of the syllabus and add some dates to help you plan. The syllabus is designed like most college courses, so using it will be excellent preparation for further education. 4. Begin the student working in the Introduction and Chapter 1. Using the syllabus as a guide, allow the student to move at a comfortable pace making sure they understand the material. You may customize the syllabus and move faster or slower to achieve the optimal learning environment for your student. 5. You have FREE Homework Help! If you need help, start with a visit to the website at www.askdrcallahan.com and go to Homework Help. -

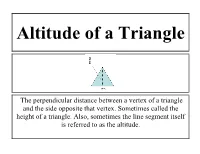

The Perpendicular Distance Between a Vertex of a Triangle and the Side Opposite That Vertex

Altitude of a Triangle The perpendicular distance between a vertex of a triangle and the side opposite that vertex. Sometimes called the height of a triangle. Also, sometimes the line segment itself is referred to as the altitude. Base (of a Polygon) For two-dimensional figures, any side can be a base. Typically, however, the bottom side, on which the polygon ‘sits,’ is called the base. Coordinate Plane A two-dimensional surface on which points are plotted and located by their x and y coordinates. Coordinate Point of a Plane A pair of numbers defining the position of a point on a two- dimensional plane. Cone A three dimensional figure with a circular or elliptical base and one vertex. Converse of Pythagorean Theorem If the square of the length of the longest side of a triangle is equal to the sum of the squares of the lengths of the other two sides, the triangle is a right triangle. Cubed Root One of three identical factors of a number that is the product of those factors. Cylinder A three dimensional object with two parallel, congruent, circular bases. Deductive Reasoning The process by which one makes conclusions using known facts, definitions, rules, or properties. Diameter The distance across a circle through its center. The line segment that includes the center and whose endpoints lie on the circle. Distance Formula An application of the Pythagorean Theorem based on the distance between two points. Geometric Solid The collective term of all bounded three dimensional geometric figures. Height of Solids The vertical height (or altitude) which is the perpendicular distance from the top down to the base.