The Neo-Fisher Effect: Econometric Evidence from Empirical and Optimizing Models

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Fisher Effect: a Review

Munich Personal RePEc Archive On The Fisher Effect: A Review Bosupeng, Mpho University of Botswana 2016 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/77916/ MPRA Paper No. 77916, posted 27 Mar 2017 14:07 UTC On The Fisher Effect: A Review Author Name: Mpho Bosupeng On The Fisher Effect: A Review Abstract The Fisher effect proposes that in the long run, nominal interest rates trend positively with inflation. In numerous studies the long run Fisher effect has been proved several times as compared to the short run Fisher effect phenomenon. The reason is in the long run, interest rates exhibit minimum volatility therefore resulting in the long run association. Even though the literature has been impressive in terms of validating the hypothesis, many central banks and policy makers have been lost in the lurch regarding the overall standpoint of the Fisher parity. This paper reviews the Fisher effect and examines factors that impinge on the hypothesis namely: inflation targeting, data set range and the regulation of the financial system. JEL: E43 KEYWORDS: Fisher effect; interest rates; inflation Introduction The Fisher effect is an equilibrium relation every central bank values and appreciates. The theory postulates that nominal interest rates rise together with inflation in the long run while real interest rates remain indifferent to this transaction following Fisher (1930). Many central banks securities such as certificates and bonds usually have fixed real interest rates. In practical terms, real interests are not always stagnant. In effect, the direct relationship between nominal interest rates and inflation changes over time which impinges on the Fisher effect. -

Testing the Fisher Hypothesis in the Presence of Structural Breaks and Adaptive Inflationary Expectations: Evidence from Nigeria

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Uyaebo, Stephen O. U. et al. Article Testing the Fisher hypothesis in the presence of structural breaks and adaptive inflationary expectations: Evidence from Nigeria CBN Journal of Applied Statistics Provided in Cooperation with: The Central Bank of Nigeria, Abuja Suggested Citation: Uyaebo, Stephen O. U. et al. (2016) : Testing the Fisher hypothesis in the presence of structural breaks and adaptive inflationary expectations: Evidence from Nigeria, CBN Journal of Applied Statistics, ISSN 2476-8472, The Central Bank of Nigeria, Abuja, Vol. 07, Iss. 1, pp. 333-358 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/191679 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

Nber Working Paper Series Searching for Irving Fisher

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES SEARCHING FOR IRVING FISHER Kris James Mitchener Marc D. Weidenmier Working Paper 15670 http://www.nber.org/papers/w15670 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 January 2010 We thank Michael Bordo, Richard Burdekin, Andy Rose, Eric Swanson, and participants at UC Berkeley, the San Francisco Fed, and the ASSA meetings for comments and suggestions. Mitchener acknowledges the generous financial support of the Hoover Institution while in residence as the W. Glenn Campbell and Rita Ricardo-Campbell National Fellow. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2010 by Kris James Mitchener and Marc D. Weidenmier. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Searching for Irving Fisher Kris James Mitchener and Marc D. Weidenmier NBER Working Paper No. 15670 January 2010 JEL No. E4,G1,N2 ABSTRACT There is a long-standing debate as to whether the Fisher effect operated during the classical gold standard period. We break new ground on this question by developing a market-based measure of general inflation expectations during the gold standard. Since the gold-silver price ratio was widely used to track inflation during the gold standard period, we are able to derive a measure of inflation expectations using the interest-rate differential between Austrian silver and gold perpetuity bonds with identical terms. -

Threshold Cointegration Test of the Fisher Effect Biyong Xu Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2004 Threshold cointegration test of the Fisher effect Biyong Xu Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Finance Commons, and the Finance and Financial Management Commons Recommended Citation Xu, Biyong, "Threshold cointegration test of the Fisher effect " (2004). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 1207. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/1207 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Threshold cointegration test of the Fisher effect by Biyong Xu A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Economics Program of Study Committee: Barry Falk, Major Professor Helle Bunzel Wayne Fuller Peter Orazem John Schroeter Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2004 Copyright © Biyong Xu, 2004. All rights reserved. UMI Number: 3158382 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

The Early History of the Real/Nominal Interest Rate Relationship

THE EARLY HISTORY OF THE REAL/NOMINAL INTEREST RATE RELATIONSHIP Thomas M. Humphrey The proposition that the real rate of interest equals century classical and neoclassical monetary theorists, the nominal rate minus the expected rate of inflation (3) that it was presented in its modern form by the (or alternatively, the nominal rate equals the real end of the century, and therefore (4) that the notion rate plus expected inflation) has a long history ex- that it is a 20th century invention is totally erroneous. tending back more than 240 years. William Douglass In documenting these points, the article traces the articulated the idea as early as the 1740s to explain pre-20th century evolution of the real/nominal rate how the overissue of colonial currency and the re- analysis from its earliest origins to its culmination in sulting depreciation of paper money relative to coin Fisher’s Appreciation and Interest. As a preliminary raised the yield on loans denominated in paper com- step, however, it is necessary to sketch the basic pared to the yield on loans denominated in silver coin. outlines of this traditional analysis in order to demon- In 1811 Henry Thornton used the same notion to ex- strate how earlier writers contributed to it. plain how an inflation premium was incorporated into and generated a rise in British interest rates during Key Propositions the Napoleonic wars. Jacob de Haas, writing in 1889, employed the real/nominal rate idea to account for the As usually presented; the real/nominal interest “third (inflationary) element” in interest rates, the rate relationship expresses the nominal rate as the other two being a reward for capital and a payment sum of the real rate and a premium for expected for risk. -

'Ecozone': Implications for Monetary Models of Exchange Rate Determinati

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Validity Assessments of International Parity in the ‘Ecozone’: Implications for Monetary Models of Exchange Rate Determination Mogaji, Peter Kehinde University of Sunderland in London 10 June 2019 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/98945/ MPRA Paper No. 98945, posted 11 Mar 2020 13:06 UTC Validity Assessments of International Parity in the ‘Ecozone’: Implications for Monetary Models of Exchange Rate Determination by Peter Kehinde Mogaji University of Sunderland in London Abstract In proposing monetary integration, the fifteen-member Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) resolved to evolve and adopt a single currency, ‘eco’ across the African sub-continent by January 2020.This proposed monetary region is consequently styled by this author as ‘proposed Ecozone’. This paper appraised the international parity conditions in the proposed monetary union with specific focus on purchasing power parity (PPP), international Fisher Effect (IFE) and uncovered interest parity (UIP). The examination of simultaneous validity of these postulations and theories in the cases of the 15-countries were performed through the investigation of directions of bilateral relationship of the countries of the Ecozone. Monthly, quarterly and annual data spanning averagely over a period of 28 years between 1990 and 2017 were employed in this study. Residual-based cointegration test methods of Engle-Granger, Philip-Ouliaris and Park’s Added Variable and the Johansen cointegration tests were applied in evaluating these parity conditions. Results generated by various empirical estimations generally revealed that the international parity theoretical propositions of absolute PPP, relative PPP, international Fisher Effects and the uncovered interest parity are hugely not valid across the proposed ‘Ecozone’. -

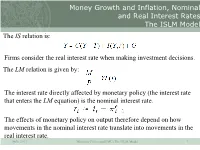

Money Growth and Inflation, Nominal and Real Interest Rates the ISLM Model the IS Relation Is

Money Growth and Inflation, Nominal and Real Interest Rates The ISLM Model The IS relation is: Firms consider the real interest rate when making investment decisions. The LM relation is given by: The interest rate directly affected by monetary policy (the interest rate that enters the LM equation) is the nominal interest rate. The effects of monetary policy on output therefore depend on how movements in the nominal interest rate translate into movements in the real interest rate. SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: The ISLM Model 1 Figure: Nominal and Real One-Year T-Bill Rates in the United States since 1978 SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: The ISLM Model 2 Figure: Expected and actual inflation rates for Germany, 1972 -2005 SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: The ISLM Model 3 Money Growth and Inflation, Nominal and Real Interest Rates The ISLM Model • Higher money growth leads to lower nominal interest rates in the short run but to higher nominal interest rates in the medium run. • Higher money growth leads to lower real interest rates in the short run but has no effect on real interest rates in the medium run. SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: The ISLM Model 4 Figure: Equilibrium Output and Interest Rates The ISLM Model The equilibrium level of output and the equilibrium nominal interest rate are given by the intersection of the IS curve and the LM curve. The real interest rate equals the nominal interest rate minus expected inflation. SuSe 2013 Monetary Policy and EMU: The ISLM Model 5 Figure: The Short-Run Effects of an Increase in Money Growth The ISLM Model An increase in money growth increases the real money stock (M/P) in the short run. -

Redalyc.INTEREST RATES, FISHER EFFECT and ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT in TURKEY, 1989-2011

Revista Galega de Economía ISSN: 1132-2799 [email protected] Universidade de Santiago de Compostela España Güris, Selahattin; Güris, Burak; Ün, Turgut INTEREST RATES, FISHER EFFECT AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN TURKEY, 1989-2011 Revista Galega de Economía, vol. 25, núm. 2, 2016, pp. 79-84 Universidade de Santiago de Compostela Santiago de Compostela, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=39148510008 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative INTEREST RATES, FISHER EFFECT AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN TURKEY, 1989-2011 Prof. Dr. Selahattin GÜRİŞ1 Assoc. Prof. Dr. Burak GÜRİŞ2 Assist. Prof. Dr. Turgut ÜN3 1,3Mármara University and 2 Istambul University, Turkey Abstract: This paper investigates the validity of the Fisher Hypothesis in Turkey covering the period 2003 – 2012. To test validity of Fisher Hypothesis, this paper uses an Autoregressive Distributed Lag test for threshold cointegration recently introduced in the literature by Li and Lee (2010). The empirical results which are obtained from this paper indicate that Fisher hypothesis is valid for Turkey, meaning nominal interest rates would be an important leading indicator for inflation. Keywords: ADL threshold cointegration test, Fisher hypothesis JEL: C32, E43 1. Introduction A linkage between nominal interest rate and inflation, known as the Fisher hypothesis, has attracted the attention of both economists and policy makers. The Fisher hypothesis, introduced by Fisher (1930), states that the expected nominal asset returns should move one for one with expected inflation. -

A Study of the Fisher Effect

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES THENON-ADJUSTMENT OF NOMINAL INTEREST RATES: A STUDY OF THE FISHER EFFECT Lawrence H. Summers Working Paper No. 836 NATIONALBUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge MA. 02138 January 1982 This paper was presented at the NBER Conference on Inflation and Financial Markets, Cambridge, Massachusetts, May 15—16, 1981. It was also presented at the Arthur Okun Memorial Conference at Columbia University on September 25, 1981. I am indebted to George Fenn and Robert Barsky for extremely capable research assistance and many useful discussions. The research reported here is part of the NBER's research program in Taxation. Any opinions expressed are those of the author and not those of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER Working Paper #836 January 1982 The Non—Adjustment of Nominal Interest Rates: A Study of the Fisher Effect ABSTRACT This paper critically re—examines theory and evidence on the relation- ship between interest rates and inflation. It concludes that there is no evidence that interest rates respond to inflation in the way that classical or Keynesian theories suggest. For the period 1860—1940, it does not appear that inflationary expectations had any significant impact on rates of inflation in the short or long run. During the post—war period interest rates do appear to be affected by inflation. However, the effect is much smaller than any theory which recognizes tax effects would predict. Further- more,all the power in the inflation interest rate relationship comes from the 1965—1971 period. Within the 1950's or 1970's, the relationship is both statistically and substantively insignificant. -

An Examination of Fisher Effect for Selected New EU Member States

International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues Vol. 4, No. 4, 2014, pp.956-959 ISSN: 2146-4138 www.econjournals.com An Examination of Fisher Effect for Selected New EU Member States Harun UCAK Mugla Sitki Kocman University, Fethiye Faculty of Business, Mugla, Turkey. Email: [email protected] Ilhan OZTURK Cag University, Faculty of Economics and Business, 33800, Mersin, Turkey. Tel: +90 324 6514828, Email: [email protected] Alper ASLAN Nevsehir University, Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, 50300, Nevsehir, Turkey. Tel: +90 3842281110 Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT: The relationship between interest rates and inflation which is called Fisher effect has been investigated in both theoretical and empirical economics in vast literature. The contribution of this paper to the literature is to test the Fisher effect for the selected four transition economies that are also new EU member states. The empirical analysis is conducted by allowing for a structural break that takes place in year 2004. In this study, a case-wise bootstrap approach empirical method which developed by Hatemi-J and Hacker (2005) is used and the results support a tax adjusted Fisher effect in the presence of a structural break. Keywords: Fisher Effect; New EU Member States; Monetary Policy; Transition Economies. JEL Classifications: E40; E43; E47; F36; P24 1. Introduction The fisher effect hypothesis was formalized by Fisher (1930) and it states that a permanent change in the rate of expected inflation will cause an equal change in the nominal interest rate in the long run. Thereby, the real interest rate would remain unchanged in response to a monetary shock if the Fisher effect holds. -

An Empirical Evidence of Fisher Effect in Bangladesh: a Time- Series Approach

An Empirical Evidence of Fisher Effect in Bangladesh: A Time- Series Approach Md. Gazi Salah Uddin Lecturer School of Business Presidency University Dhaka, Bangladesh Email: [email protected] Md. Mahmudul Alam Deputy Manager Customer Relationship Management Brands, Commercial Division Grameenphone Ltd. Dhaka, Bangladesh Email: [email protected] Kazi Ashraful Alam Assistant Professor Faculty of Business ASA University Bangladesh Dhaka, Bangladesh Email: [email protected] Citation Reference: Uddin, M.G.S, Alam, M.M., and Alam, K.A. 2008. An Empirical Evidence of Fisher Effect in Bangladesh: A Time-Series Approach, ASA University Review, 2(1), 1-8. (ISSN 1997-6925; Publisher- ASA University, Bangladesh) This is a pre-publication copy. The published article is copyrighted by the publisher of the journal. 0 An Empirical Evidence of Fisher Effect in Bangladesh: A Time- Series Approach Md. Gazi Salah Uddin 1, Md. Mahmudul Alam 2, Kazi Ashraful Alam 3 Abstract This paper is an attempt to trace the relationship between interest rates and rates of inflation in the economy of Bangladesh. In view of this, a time series approach is considered to examine the empirical evidence of Fisher’s effect in the country. By applying OLS and Unit Root test, the estimated value is used to determine the casual relationship between interest rates and inflation for the monthly sample period of August 1996 to December 2003. The empirical results suggest that there does not exist any co- movement of inflation with interest rates and the relationship between the variables is also not significant for Bangladesh. Further, the trends advocate that the inflation premium, equal to expected inflation that investors add to real-risk free rate of return, is ineffective in the country. -

The Fisher Effect and the Financial Crisis of 2008

The Fisher Effect and the Financial Crisis of 2008 David Glasner MERCATUS WORKING PAPER All studies in the Mercatus Working Paper series have followed a rigorous process of academic evaluation, including (except where otherwise noted) at least one double-blind peer review. Working Papers present an author’s provisional findings, which, upon further consideration and revision, are likely to be republished in an academic journal. The opinions expressed in Mercatus Working Papers are the authors’ and do not represent official positions of the Mercatus Center or George Mason University. David Glasner. “The Fisher Effect and the Financial Crisis of 2008.” Mercatus Working Paper, Mercatus Center at George Mason University, Arlington, VA, 2018. Abstract This paper uses the Fisher equation relating the nominal interest rate to the real interest rate and expected inflation to provide a deeper explanation of the financial crisis of 2008 and the subsequent recovery than attributing it to the bursting of the housing-price bubble. The paper interprets the Fisher equation as an equilibrium condition in which expected returns from holding real assets and cash are equalized. When inflation expectations decline, the return to holding cash rises relative to holding real assets. If nominal interest rates are above the zero lower bound, equilibrium is easily restored by adjustments in nominal interest rates and asset prices. But at the zero lower bound, nominal interest rates cannot fall, forcing the entire adjustment onto falling asset prices, thereby raising the expected real return from holding assets. Such an adjustment seems to have triggered the financial crisis of 2008, when the Federal Reserve delayed reducing nominal interest rates out of a misplaced fear of inflation in the summer of 2008 when the economy was already contracting rapidly.