Divine Law and Philosophy in Plato and Maimonides

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Philosophical Counseling As a Philosophical Caretaking Practice

On Philosophical Counseling as a Philosophical Caretaking Practice A THESIS SUBMITTED ON THE 23'd DAY OF JULY OF 2014 TO THE DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE SCHOOL OF LmERAL ARTS OF TULANE UNIVERSITY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY Gilberto Vargas-Gonzalez APPROVED: &~ 4. Ronna Burger, Ph.D., Director /hv VJvf!Jy-- Richard Velkley, Ph.D. ~.PhD -" On Philosophical Counseling as a Philosophical Caretaking Practice AN ABSTRACT SUBMITTED ON THE 23 rd DAY OF JULY OF 2014 TO THE DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE SCHOOL OF LffiERAL ARTS OF TULANE UNIVERSITY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY Gilberto Vargas-Gonzalez APPROVED: --+ffi-",/lvlJ.,--",-",,-,~c:.=.>p>~_ Ronna Burger, Ph.D., Director y~~ Richard Velkley, Ph.D. ~- Michael Zimmerman, Ph.D. While “philosophical counseling” emerged in the 1980’s as a new form of caretaking practice, it can be understood as an attempt to re-embrace a tradition that goes back to the ancients, with their conception of philosophy as a “way of life.” This study discusses elements of that tradition in order to provide a theoretical-historical framework for the modern practice of philosophical counseling. The central figure for this philosophic tradition is Socrates. The present study focused on his notion of the “the examined life,” while considering some doctrines in Hellenistic philosophy as further expressions of the Socratic tradition. As represented in the Platonic dialogues, Socrates exhibits “the examined life” by engaging in the practice of philosophy as some kind of “care of the soul.” Though he speaks on occasion of the “conversion” that may be required for the commitment to this philosophic practice, it is carried out, in dialogical settings, through the rational-cognition dimension of reason and argument, undertaken with a basic critical stance. -

Spring 2019 Volume 45 Issue 2

Spring 2019 Volume 45 Issue 2 155 Ian Dagg Natural Religion in Montesquieu’s Persian Letters and The Spirit of the Laws 179 David N. Levy Aristotle’s “Reply” to Machiavelli on Morality 199 Ashleen Menchaca-Bagnulo “Deceived by the Glory of Caesar”: Humility and Machiavelli’s Founder Reviews Essays: 223 Marco Andreacchio Mastery of Nature, edited by Svetozar Y. Minkov and Bernhardt L. Trout 249 Alex Priou The Eccentric Core, edited by Ronna Burger and Patrick Goodin 269 David Lewis Schaefer The Banality of Heidegger by Jean-Luc Nancy Book Reviews: 291 Victor Bruno The Techne of Giving by Timothy C. Campbell 297 Jonathan Culp Orwell Your Orwell by David Ramsay Steele 303 Fred Erdman Becoming Socrates by Alex Priou 307 David Fott Roman Political Thought by Jed W. Atkins 313 Steven H. Frankel The Idol of Our Age by Daniel J. Mahoney 323 Michael Harding Leo Strauss on Nietzsche’s Thrasymachean-Dionysian Socrates by Angel Jaramillo Torres 335 Marjorie Jeffrey Aristocratic Souls in Democratic Times, edited by Richard Avramenko and Ethan Alexander-Davey 341 Peter Minowitz The Bleak Political Implications of Socratic Religion by Shadia B. Drury 347 Charles T. Rubin Mary Shelley and the Rights of the Child by Eileen Hunt Botting 353 Thomas Schneider From Oligarchy to Republicanism by Forrest A. Nabors 357 Stephen Sims The Legitimacy of the Human by Rémi Brague ©2019 Interpretation, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the contents may be reproduced in any form without written permission of the publisher. ISSN 0020-9635 Editor-in-Chief Timothy W. Burns, Baylor University General Editors Charles E. -

Western Religious Beliefs and Environment: Personal Reflections on the Religion and Environment

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2000 Western religious beliefs and environment: Personal reflections on the religion and environment Varya Petrosyan The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Petrosyan, Varya, "Western religious beliefs and environment: Personal reflections on the eligionr and environment" (2000). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5525. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5525 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University o fMONTANA Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ** Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature ** Yes, I grant permission 1/ No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature t ^ Date 03 Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. QtfPestem (s&elifpaus (R eliefs and GLnviranment Personal (dReflectiaw an the G&eligian and (SLnviranment by Varya Petrosyan B.A. Georgian Academy of Sciences, Institute of Ecology, Environmental Protection and Agribusiness, 1998 presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science The University of Montana 2000 Approved by: Chairperson s Dean, Graduate School Date UMI Number: EP40989 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

A Philosophical and Historical Analysis of Cosmology from Copernicus to Newton

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2017 Scientific transformations: a philosophical and historical analysis of cosmology from Copernicus to Newton Manuel-Albert Castillo University of Central Florida Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Castillo, Manuel-Albert, "Scientific transformations: a philosophical and historical analysis of cosmology from Copernicus to Newton" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5694. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5694 SCIENTIFIC TRANSFORMATIONS: A PHILOSOPHICAL AND HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF COSMOLOGY FROM COPERNICUS TO NEWTON by MANUEL-ALBERT F. CASTILLO A.A., Valencia College, 2013 B.A., University of Central Florida, 2015 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the department of Interdisciplinary Studies in the College of Graduate Studies at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2017 Major Professor: Donald E. Jones ©2017 Manuel-Albert F. Castillo ii ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to show a transformation around the scientific revolution from the sixteenth to seventeenth centuries against a Whig approach in which it still lingers in the history of science. I find the transformations of modern science through the cosmological models of Nicholas Copernicus, Johannes Kepler, Galileo Galilei and Isaac Newton. -

An Atheistic Argument from Ugliness

AN ATHEISTIC ARGUMENT FROM UGLINESS SCOTT F. AIKIN & NICHOLAOS JONES Vanderbilt University University of Alabama in Huntsville Author posting. (c) European Journal of Philosophy of Religion 7.1 (Spring 2015). This is the author's version of the work. It is posted here for personal use, not for redistribution. The definitive version is available at http://www.philosophy-of- religion.eu/contents19.html This is a penultimate draft. Please cite only the published version. Abstract The theistic argument from beauty has what we call an ‘evil twin’, the argument from ugliness. The argument yields either what we call ‘atheist win’, or, when faced with aesthetic theodicies, ‘agnostic tie’ with the argument from beauty. 1 AN ATHEISTIC ARGUMENT FROM UGLINESS I. EVIL TWINS FOR TELEOLOGICAL ARGUMENTS The theistic argument from beauty is a teleological argument. Teleological arguments take the following form: 1. The universe (or parts of it) exhibit property X 2. Property X is usually (if not always) brought about by the purposive actions of those who created objects for them to be X. 3. The cases mentioned in Premise 1 are not explained (or fully explained) by human action 4. Therefore: The universe is (likely) the product of a purposive agent who created it to be X, namely God. The variety of teleological arguments is as broad as substitution instances for X. The standard substitutions have been features of the universe (or it all) fine-tuned for life, or the fact of moral action. One further substitution has been beauty. Thus, arguments from beauty. A truism about teleological arguments is that they have evil twins. -

Some Strictures Upon the Sacred Story Recorded in the Book of Esther (1775)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Electronic Texts in American Studies Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 1775 Some Strictures upon the Sacred Story Recorded in the Book of Esther (1775) Oliver Noble M.A. Pastor of a Church in Newbury (Mass.) Reiner Smolinski , Editor Georgia State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/etas Part of the American Studies Commons Noble, Oliver M.A. and Smolinski, Reiner , Editor, "Some Strictures upon the Sacred Story Recorded in the Book of Esther (1775)" (1775). Electronic Texts in American Studies. 43. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/etas/43 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Texts in American Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Oliver Noble his majesty’s faithful colonists (Mordecai and Queen Esther) Some Strictures upon the Sacred Story through the infamous Stamp Act (Haman’s injunction against Recorded in the Book of Esther (1775) the Israelites). With such obvious parallels from the Good Book, Noble thundered against Haman’s greed but also proph- esied that the present crisis will soon pass over and America be O N (1733/4–92). Born in Hebron, Connecticut, LIVER OBLE vindicated in the eyes of King George. Noble graduated from Yale in 1757, but stayed on as a tutor un- Most interesting in this context is that Noble presented til he received his second degree in 1759. -

Against the Heteronomy of Halakhah: Hermann Cohen's Implicit Rejection of Kant's Critique of Judaism

Against the Heteronomy of Halakhah: Hermann Cohen’s Implicit Rejection of Kant’s Critique of Judaism George Y. Kohler* “Moses did not make religion a part of virtue, but he saw and ordained the virtues to be part of religion…” Josephus, Against Apion 2.17 Hermann Cohen (1842–1918) was arguably the only Jewish philosopher of modernity whose standing within the general philosophical developments of the West equals his enormous impact on Jewish thought. Cohen founded the influential Marburg school of Neo-Kantianism, the leading trend in German Kathederphilosophie in the second half of the nineteenth and the first decade of the twentieth century. Marburg Neo-Kantianism cultivated an overtly ethical, that is, anti-Marxist, and anti-materialist socialism that for Cohen increasingly concurred with his philosophical reading of messianic Judaism. Cohen’s Jewish philosophical theology, elaborated during the last decades of his life, culminated in his famous Religion of Reason out of the Sources of Judaism, published posthumously in 1919.1 Here, Cohen translated his neo-Kantian philosophical position back into classical Jewish terms that he had extracted from Judaism with the help of the progressive line of thought running from * Bar-Ilan University, Department of Jewish Thought. 1 Hermann Cohen, Religion der Vernunft aus den Quellen des Judentums, first edition, Leipzig: Fock, 1919. I refer to the second edition, Frankfurt: Kaufmann, 1929. English translation by Simon Kaplan, Religion of Reason out of the Sources of Judaism (New York: Ungar, 1972). Henceforth this book will be referred to as RR, with reference to the English translation by Kaplan given after the German in square brackets. -

The Teleological Argument Looks at the Purpose of Something and from That

The teleological argument looks at the purpose of something and Cosmological arguments start with observations about the way The Third Way: contingency and necessity William Paley (1742 – 1805) observed that complex objects work from that he reasons that God must exist. Aquinas (1224 – 1274) the universe works and from there these try to explain why the with regularity, (seasons, gravity, etc). This order seems to be the gave five ‘ways’ of proving God exists and this, his teleological universe exists. Aquinas gives three versions of the cosmological Aquinas’ point here is that everything in the universe is result of the work of a designer who has put this regularity and arguments, starting with three different (although similar) argument, is the fifth of his five ways. contingent – it relies on something to have brought it into order into place deliberately and with purpose. For example, the observations: motion, causation and contingency. Aquinas, influenced by Aristotle, believed that all things have a existence and also things to let it continue to exist. eye is constructed perfectly to see. For Palely, all of this pointed to purpose, but we cannot achieve that purpose without something The First Way: the unmoved mover a designer, who is God. In nature, there are things that are possible ‘to be’ and to make it happen – some sort of guide, which is God. Inspired by Aristotle, Aquinas noticed that the ways in which things ‘not to be’ (contingent beings) The analogy of the watch move or change (changing state is a form of motion) must mean These things could not always have existed because that something has made that motion take place. -

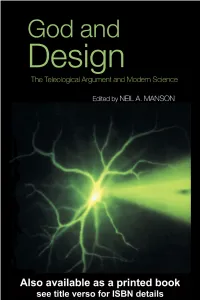

God and Design: the Teleological Argument and Modern Science

GOD AND DESIGN Is there reason to think a supernatural designer made our world? Recent discoveries in physics, cosmology, and biochemistry have captured the public imagination and made the design argument—the theory that God created the world according to a specific plan—the object of renewed scientific and philosophical interest. Terms such as “cosmic fine-tuning,” the “anthropic principle,” and “irreducible complexity” have seeped into public consciousness, increasingly appearing within discussion about the existence and nature of God. This accessible and serious introduction to the design problem brings together both sympathetic and critical new perspectives from prominent scientists and philosophers including Paul Davies, Richard Swinburne, Sir Martin Rees, Michael Behe, Elliott Sober, and Peter van Inwagen. Questions raised include: • What is the logical structure of the design argument? • How can intelligent design be detected in the Universe? • What evidence is there for the claim that the Universe is divinely fine-tuned for life? • Does the possible existence of other universes refute the design argument? • Is evolutionary theory compatible with the belief that God designed the world? God and Design probes the relationship between modern science and religious belief, considering their points of conflict and their many points of similarity. Is God the “master clockmaker” who sets the world’s mechanism on a perfectly enduring course, or a miraculous presence continually intervening in and altering the world we know? Are science and faith, or evolution and creation, really in conflict at all? Expanding the parameters of a lively and urgent contemporary debate, God and Design considers the ways in which perennial questions of origin continue to fascinate and disturb us. -

Developing and Strengthening Belief in God I

DEVELOPING AND STRENGTHENING BELIEF IN GOD I First Cause (Cosmological) and Design (Teleological) Arguments he cornerstone of Jewish belief is that God created the universe ex nihilo with Tthe Torah as His Divine plan and that He continually guides and supervises His creation. Nevertheless, there are many people who do not share this belief, or at least question it. There is a need, therefore, to present a range of approaches to developing and strengthening belief in God. The traditional Jewish approach to belief in God is based on the Exodus from Egypt and hashgachah pratit (Divine Providence). These approaches are discussed in the Morasha classes on Passover, Torah M’Sinai, and Hashgachah Pratit. The goal of this series of classes is to present additional approaches to belief – those based on logic and science – to help strengthen one’s belief in God. Specifically, this series will present three arguments for the existence of God. The first class, after defining the aim of the series on the whole, will explore two deductive arguments for the existence of God, namely the First Cause or Cosmological Argument, and the Design or Teleological Argument. The second class in the series will explore the inductive approach, focusing on the Moral Argument. In order to help students digest the logical force of the arguments presented, the series will conclude with an exploration of the decision making process. In this first class we will explore the following questions: Where did the world come from? Does it make sense that the world always existed? What does modern science have to say about the subject? Does the design found in nature imply that there is a Divine Designer? Does the Theory of Evolution explain this phenomenon? 1 Core Beliefs DEVELOPING & STRENGTHENING BELIEF I Class Outline: Section I. -

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title The anthropology of incommensurability Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3vx742f4 Journal Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, 21(2) ISSN 0039-3681 Author Biagioli, M Publication Date 1990 DOI 10.1016/0039-3681(90)90022-Z Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California MARIO BIAGIOLP’ THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF INCOMMENSURABILITY I. Incommensurability and Sterility SINCE IT entered the discourse of history and philosophy of science with Feyerabend’s “Explanation, Reduction, and Empiricism” and Kuhn’s The Structure of Scient$c Revolutions, the notion of incommensurability has problematized the debate on processes of theory-choice.’ According to Kuhn, two scientific paradigms competing for the explanation of roughly the same set of natural phenomena may not share a global linguistic common denominator. As a result, the possibility of scientific communication and dialogue cannot be taken for granted and the process of theory choice can no longer be reduced to the simple picture presented, for example, by the logical empiricists. By analyzing the dialogue (or rather the lack of it) between Galileo and the Tuscan Aristotelians during the debate on buoyancy in 1611-1613, I want to argue that incommensurability between competing paradigms is not just an unfortunate problem of linguistic communication, but it plays an important role in the process of scientific change and paradigm-speciation. The breakdown of communication during the -

Salomon Maimon and the Metaphorical Nature of Language

zlom2 12.11.2009 16:02 Stránka 167 Pol Capdevila SALOMON MAIMON AND THE METAPHORICAL NATURE OF LANGUAGE LUCIE PARGAČOVÁ This article is concerned with the metaphorical nature of language in the conception of Salomon Maimon (1753–1800), one of the most distinctive figures of post-Kantian philosophy. He was continuously challenging the theories that attributed a metaphorical character to language, which were widespread in eighteenth-century British, French, and German philosophy. Particularly notable was his attack on Johann Georg Sulzer (1720–1779). The core of the dispute concerned different views on the relationship between the sphere of the senses and the sphere of the intellect. Whereas Sulzer understood them simply as analogical, Maimon dissolved the disparity, convinced that each stems, albeit separately, from the transcendental activity of consciousness. He applied this method of argumentation also in essays on literal meaning and figurative meaning. Salomon Maimon und der metaphorische Charakter der Sprache Der Aufsatz beschäftigt sich mit dem metaphorischen Charakter der Sprache im Denken von Salomon Maimon (1753–1800). Dieser herausragende Vertreter post-kantianischer Philosophie polemisierte wiederholt mit in der britischen, französischen und deutschen Philosophie des 18. Jahrhunderts verbreiteten Theorien, die der Sprache metaphorischen Charakter zuschrieben. Maimons Angriff richtete sich vor allem gegen Johann Georg Sulzer (1720–1779). Der Konflikt drehte sich um verschiedene Auffassungen der Beziehung zwischen dem Bereich des Sinnlichen und dem des Intelligiblen: Während Sulzer diese Bereiche unproblematisch als einander analog verstand, löste Maimon ihre Unterschied- lichkeit auf, da er überzeugt war, dass beide der transzendentalen Tätigkeit des Bewusst- seins entspringen. Diese Argumentationlinie verfolgte er auch in seinen Überlegungen zur eigentlichen und uneigentlichen Bedeutung.