Regular Expressions and Automata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theory of Computer Science

Theory of Computer Science MODULE-1 Alphabet A finite set of symbols is denoted by ∑. Language A language is defined as a set of strings of symbols over an alphabet. Language of a Machine Set of all accepted strings of a machine is called language of a machine. Grammar Grammar is the set of rules that generates language. CHOMSKY HIERARCHY OF LANGUAGES Type 0-Language:-Unrestricted Language, Accepter:-Turing Machine, Generetor:-Unrestricted Grammar Type 1- Language:-Context Sensitive Language, Accepter:- Linear Bounded Automata, Generetor:-Context Sensitive Grammar Type 2- Language:-Context Free Language, Accepter:-Push Down Automata, Generetor:- Context Free Grammar Type 3- Language:-Regular Language, Accepter:- Finite Automata, Generetor:-Regular Grammar Finite Automata Finite Automata is generally of two types :(i)Deterministic Finite Automata (DFA)(ii)Non Deterministic Finite Automata(NFA) DFA DFA is represented formally by a 5-tuple (Q,Σ,δ,q0,F), where: Q is a finite set of states. Σ is a finite set of symbols, called the alphabet of the automaton. δ is the transition function, that is, δ: Q × Σ → Q. q0 is the start state, that is, the state of the automaton before any input has been processed, where q0 Q. F is a set of states of Q (i.e. F Q) called accept states or Final States 1. Construct a DFA that accepts set of all strings over ∑={0,1}, ending with 00 ? 1 0 A B S State/Input 0 1 1 A B A 0 B C A 1 * C C A C 0 2. Construct a DFA that accepts set of all strings over ∑={0,1}, not containing 101 as a substring ? 0 1 1 A B State/Input 0 1 S *A A B 0 *B C B 0 0,1 *C A R C R R R R 1 NFA NFA is represented formally by a 5-tuple (Q,Σ,δ,q0,F), where: Q is a finite set of states. -

Cs 61A/Cs 98-52

CS 61A/CS 98-52 Mehrdad Niknami University of California, Berkeley Mehrdad Niknami (UC Berkeley) CS 61A/CS 98-52 1 / 23 Something like this? (Is this good?) def find(string, pattern): n= len(string) m= len(pattern) for i in range(n-m+ 1): is_match= True for j in range(m): if pattern[j] != string[i+ j] is_match= False break if is_match: return i What if you were looking for a pattern? Like an email address? Motivation How would you find a substring inside a string? Mehrdad Niknami (UC Berkeley) CS 61A/CS 98-52 2 / 23 def find(string, pattern): n= len(string) m= len(pattern) for i in range(n-m+ 1): is_match= True for j in range(m): if pattern[j] != string[i+ j] is_match= False break if is_match: return i What if you were looking for a pattern? Like an email address? Motivation How would you find a substring inside a string? Something like this? (Is this good?) Mehrdad Niknami (UC Berkeley) CS 61A/CS 98-52 2 / 23 What if you were looking for a pattern? Like an email address? Motivation How would you find a substring inside a string? Something like this? (Is this good?) def find(string, pattern): n= len(string) m= len(pattern) for i in range(n-m+ 1): is_match= True for j in range(m): if pattern[j] != string[i+ j] is_match= False break if is_match: return i Mehrdad Niknami (UC Berkeley) CS 61A/CS 98-52 2 / 23 Motivation How would you find a substring inside a string? Something like this? (Is this good?) def find(string, pattern): n= len(string) m= len(pattern) for i in range(n-m+ 1): is_match= True for j in range(m): if pattern[j] != string[i+ -

Use Perl Regular Expressions in SAS® Shuguang Zhang, WRDS, Philadelphia, PA

NESUG 2007 Programming Beyond the Basics Use Perl Regular Expressions in SAS® Shuguang Zhang, WRDS, Philadelphia, PA ABSTRACT Regular Expression (Regexp) enhance search and replace operations on text. In SAS®, the INDEX, SCAN and SUBSTR functions along with concatenation (||) can be used for simple search and replace operations on static text. These functions lack flexibility and make searching dynamic text difficult, and involve more function calls. Regexp combines most, if not all, of these steps into one expression. This makes code less error prone, easier to maintain, clearer, and can improve performance. This paper will discuss three ways to use Perl Regular Expression in SAS: 1. Use SAS PRX functions; 2. Use Perl Regular Expression with filename statement through a PIPE such as ‘Filename fileref PIPE 'Perl programm'; 3. Use an X command such as ‘X Perl_program’; Three typical uses of regular expressions will also be discussed and example(s) will be presented for each: 1. Test for a pattern of characters within a string; 2. Replace text; 3. Extract a substring. INTRODUCTION Perl is short for “Practical Extraction and Report Language". Larry Wall Created Perl in mid-1980s when he was trying to produce some reports from a Usenet-Nes-like hierarchy of files. Perl tries to fill the gap between low-level programming and high-level programming and it is easy, nearly unlimited, and fast. A regular expression, often called a pattern in Perl, is a template that either matches or does not match a given string. That is, there are an infinite number of possible text strings. -

Lecture 18: Theory of Computation Regular Expressions and Dfas

Introduction to Theoretical CS Lecture 18: Theory of Computation Two fundamental questions. ! What can a computer do? ! What can a computer do with limited resources? General approach. Pentium IV running Linux kernel 2.4.22 ! Don't talk about specific machines or problems. ! Consider minimal abstract machines. ! Consider general classes of problems. COS126: General Computer Science • http://www.cs.Princeton.EDU/~cos126 2 Why Learn Theory In theory . Regular Expressions and DFAs ! Deeper understanding of what is a computer and computing. ! Foundation of all modern computers. ! Pure science. ! Philosophical implications. a* | (a*ba*ba*ba*)* In practice . ! Web search: theory of pattern matching. ! Sequential circuits: theory of finite state automata. a a a ! Compilers: theory of context free grammars. b b ! Cryptography: theory of computational complexity. 0 1 2 ! Data compression: theory of information. b "In theory there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice there is." -Yogi Berra 3 4 Pattern Matching Applications Regular Expressions: Basic Operations Test if a string matches some pattern. Regular expression. Notation to specify a set of strings. ! Process natural language. ! Scan for virus signatures. ! Search for information using Google. Operation Regular Expression Yes No ! Access information in digital libraries. ! Retrieve information from Lexis/Nexis. Concatenation aabaab aabaab every other string ! Search-and-replace in a word processors. cumulus succubus Wildcard .u.u.u. ! Filter text (spam, NetNanny, Carnivore, malware). jugulum tumultuous ! Validate data-entry fields (dates, email, URL, credit card). aa Union aa | baab baab every other string ! Search for markers in human genome using PROSITE patterns. aa ab Closure ab*a abbba ababa Parse text files. -

Regular Languages and Finite Automata for Part IA of the Computer Science Tripos

N Lecture Notes on Regular Languages and Finite Automata for Part IA of the Computer Science Tripos Prof. Andrew M. Pitts Cambridge University Computer Laboratory c 2012 A. M. Pitts Contents Learning Guide ii 1 Regular Expressions 1 1.1 Alphabets,strings,andlanguages . .......... 1 1.2 Patternmatching................................. .... 4 1.3 Somequestionsaboutlanguages . ....... 6 1.4 Exercises....................................... .. 8 2 Finite State Machines 11 2.1 Finiteautomata .................................. ... 11 2.2 Determinism, non-determinism, and ε-transitions. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 14 2.3 Asubsetconstruction . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ..... 17 2.4 Summary ........................................ 20 2.5 Exercises....................................... .. 20 3 Regular Languages, I 23 3.1 Finiteautomatafromregularexpressions . ............ 23 3.2 Decidabilityofmatching . ...... 28 3.3 Exercises....................................... .. 30 4 Regular Languages, II 31 4.1 Regularexpressionsfromfiniteautomata . ........... 31 4.2 Anexample ....................................... 32 4.3 Complementand intersectionof regularlanguages . .............. 34 4.4 Exercises....................................... .. 36 5 The Pumping Lemma 39 5.1 ProvingthePumpingLemma . .... 40 5.2 UsingthePumpingLemma . ... 41 5.3 Decidabilityoflanguageequivalence . ........... 44 5.4 Exercises....................................... .. 45 6 Grammars 47 6.1 Context-freegrammars . ..... 47 6.2 Backus-NaurForm ................................ -

Deterministic Finite Automata 0 0,1 1

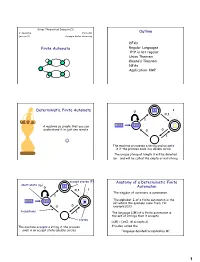

Great Theoretical Ideas in CS V. Adamchik CS 15-251 Outline Lecture 21 Carnegie Mellon University DFAs Finite Automata Regular Languages 0n1n is not regular Union Theorem Kleene’s Theorem NFAs Application: KMP 11 1 Deterministic Finite Automata 0 0,1 1 A machine so simple that you can 0111 111 1 ϵ understand it in just one minute 0 0 1 The machine processes a string and accepts it if the process ends in a double circle The unique string of length 0 will be denoted by ε and will be called the empty or null string accept states (F) Anatomy of a Deterministic Finite start state (q0) 11 0 Automaton 0,1 1 The singular of automata is automaton. 1 The alphabet Σ of a finite automaton is the 0111 111 1 ϵ set where the symbols come from, for 0 0 example {0,1} transitions 1 The language L(M) of a finite automaton is the set of strings that it accepts states L(M) = {x∈Σ: M accepts x} The machine accepts a string if the process It’s also called the ends in an accept state (double circle) “language decided/accepted by M”. 1 The Language L(M) of Machine M The Language L(M) of Machine M 0 0 0 0,1 1 q 0 q1 q0 1 1 What language does this DFA decide/accept? L(M) = All strings of 0s and 1s The language of a finite automaton is the set of strings that it accepts L(M) = { w | w has an even number of 1s} M = (Q, Σ, , q0, F) Q = {q0, q1, q2, q3} Formal definition of DFAs where Σ = {0,1} A finite automaton is a 5-tuple M = (Q, Σ, , q0, F) q0 Q is start state Q is the finite set of states F = {q1, q2} Q accept states : Q Σ → Q transition function Σ is the alphabet : Q Σ → Q is the transition function q 1 0 1 0 1 0,1 q0 Q is the start state q0 q0 q1 1 q q1 q2 q2 F Q is the set of accept states 0 M q2 0 0 q2 q3 q2 q q q 1 3 0 2 L(M) = the language of machine M q3 = set of all strings machine M accepts EXAMPLE Determine the language An automaton that accepts all recognized by and only those strings that contain 001 1 0,1 0,1 0 1 0 0 0 1 {0} {00} {001} 1 L(M)={1,11,111, …} 2 Membership problem Determine the language decided by Determine whether some word belongs to the language. -

Practical Experiments with Regular Approximation of Context-Free Languages

Practical Experiments with Regular Approximation of Context-Free Languages Mark-Jan Nederhof German Research Center for Arti®cial Intelligence Several methods are discussed that construct a ®nite automaton given a context-free grammar, including both methods that lead to subsets and those that lead to supersets of the original context-free language. Some of these methods of regular approximation are new, and some others are presented here in a more re®ned form with respect to existing literature. Practical experiments with the different methods of regular approximation are performed for spoken-language input: hypotheses from a speech recognizer are ®ltered through a ®nite automaton. 1. Introduction Several methods of regular approximation of context-free languages have been pro- posed in the literature. For some, the regular language is a superset of the context-free language, and for others it is a subset. We have implemented a large number of meth- ods, and where necessary, re®ned them with an analysis of the grammar. We also propose a number of new methods. The analysis of the grammar is based on a suf®cient condition for context-free grammars to generate regular languages. For an arbitrary grammar, this analysis iden- ti®es sets of rules that need to be processed in a special way in order to obtain a regular language. The nature of this processing differs for the respective approximation meth- ods. For other parts of the grammar, no special treatment is needed and the grammar rules are translated to the states and transitions of a ®nite automaton without affecting the language. -

Perl Regular Expressions Tip Sheet Functions and Call Routines

– Perl Regular Expressions Tip Sheet Functions and Call Routines Basic Syntax Advanced Syntax regex-id = prxparse(perl-regex) Character Behavior Character Behavior Compile Perl regular expression perl-regex and /…/ Starting and ending regex delimiters non-meta Match character return regex-id to be used by other PRX functions. | Alternation character () Grouping {}[]()^ Metacharacters, to match these pos = prxmatch(regex-id | perl-regex, source) $.|*+?\ characters, override (escape) with \ Search in source and return position of match or zero Wildcards/Character Class Shorthands \ Override (escape) next metacharacter if no match is found. Character Behavior \n Match capture buffer n Match any one character . (?:…) Non-capturing group new-string = prxchange(regex-id | perl-regex, times, \w Match a word character (alphanumeric old-string) plus "_") Lazy Repetition Factors Search and replace times number of times in old- \W Match a non-word character (match minimum number of times possible) string and return modified string in new-string. \s Match a whitespace character Character Behavior \S Match a non-whitespace character *? Match 0 or more times call prxchange(regex-id, times, old-string, new- \d Match a digit character +? Match 1 or more times string, res-length, trunc-value, num-of-changes) Match a non-digit character ?? Match 0 or 1 time Same as prior example and place length of result in \D {n}? Match exactly n times res-length, if result is too long to fit into new-string, Character Classes Match at least n times trunc-value is set to 1, and the number of changes is {n,}? Character Behavior Match at least n but not more than m placed in num-of-changes. -

Unicode Regular Expressions Technical Reports

7/1/2019 UTS #18: Unicode Regular Expressions Technical Reports Working Draft for Proposed Update Unicode® Technical Standard #18 UNICODE REGULAR EXPRESSIONS Version 20 Editors Mark Davis, Andy Heninger Date 2019-07-01 This Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr18/tr18-20.html Previous Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr18/tr18-19.html Latest Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr18/ Latest Proposed http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr18/proposed.html Update Revision 20 Summary This document describes guidelines for how to adapt regular expression engines to use Unicode. Status This is a draft document which may be updated, replaced, or superseded by other documents at any time. Publication does not imply endorsement by the Unicode Consortium. This is not a stable document; it is inappropriate to cite this document as other than a work in progress. A Unicode Technical Standard (UTS) is an independent specification. Conformance to the Unicode Standard does not imply conformance to any UTS. Please submit corrigenda and other comments with the online reporting form [Feedback]. Related information that is useful in understanding this document is found in the References. For the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see [Unicode]. For a list of current Unicode Technical Reports, see [Reports]. For more information about versions of the Unicode Standard, see [Versions]. Contents 0 Introduction 0.1 Notation 0.2 Conformance 1 Basic Unicode Support: Level 1 1.1 Hex Notation 1.1.1 Hex Notation and Normalization 1.2 Properties 1.2.1 General -

1 Alphabets and Languages

1 Alphabets and Languages Look at handout 1 (inference rules for sets) and use the rules on some exam- ples like fag ⊆ ffagg fag 2 fa; bg, fag 2 ffagg, fag ⊆ ffagg, fag ⊆ fa; bg, a ⊆ ffagg, a 2 fa; bg, a 2 ffagg, a ⊆ fa; bg Example: To show fag ⊆ fa; bg, use inference rule L1 (first one on the left). This asks us to show a 2 fa; bg. To show this, use rule L5, which succeeds. To show fag 2 fa; bg, which rule applies? • The only one is rule L4. So now we have to either show fag = a or fag = b. Neither one works. • To show fag = a we have to show fag ⊆ a and a ⊆ fag by rule L8. The only rules that might work to show a ⊆ fag are L1, L2, and L3 but none of them match, so we fail. • There is another rule for this at the very end, but it also fails. • To show fag = b, we try the rules in a similar way, but they also fail. Therefore we cannot show that fag 2 fa; bg. This suggests that the state- ment fag 2 fa; bg is false. Suppose we have two set expressions only involving brackets, commas, the empty set, and variables, like fa; fb; cgg and fa; fc; bgg. Then there is an easy way to test if they are equal. If they can be made the same by • permuting elements of a set, and • deleting duplicate items of a set then they are equal, otherwise they are not equal. -

Context Free Languages II Announcement Announcement

Announcement • About homework #4 Context Free Languages II – The FA corresponding to the RE given in class may indeed already be minimal. – Non-regular language proofs CFLs and Regular Languages • Use Pumping Lemma • Homework session after lecture Announcement Before we begin • Note about homework #2 • Questions from last time? – For a deterministic FA, there must be a transition for every character from every state. Languages CFLs and Regular Languages • Recall. • Venn diagram of languages – What is a language? Is there – What is a class of languages? something Regular Languages out here? CFLs Finite Languages 1 Context Free Languages Context Free Grammars • Context Free Languages(CFL) is the next • Let’s formalize this a bit: class of languages outside of Regular – A context free grammar (CFG) is a 4-tuple: (V, Languages: Σ, S, P) where – Means for defining: Context Free Grammar • V is a set of variables Σ – Machine for accepting: Pushdown Automata • is a set of terminals • V and Σ are disjoint (I.e. V ∩Σ= ∅) •S ∈V, is your start symbol Context Free Grammars Context Free Grammars • Let’s formalize this a bit: • Let’s formalize this a bit: – Production rules – Production rules →β •Of the form A where • We say that the grammar is context-free since this ∈ –A V substitution can take place regardless of where A is. – β∈(V ∪∑)* string with symbols from V and ∑ α⇒* γ γ α • We say that γ can be derived from α in one step: • We write if can be derived from in zero –A →βis a rule or more steps. -

Regular Expressions with a Brief Intro to FSM

Regular Expressions with a brief intro to FSM 15-123 Systems Skills in C and Unix Case for regular expressions • Many web applications require pattern matching – look for <a href> tag for links – Token search • A regular expression – A pattern that defines a class of strings – Special syntax used to represent the class • Eg; *.c - any pattern that ends with .c Formal Languages • Formal language consists of – An alphabet – Formal grammar • Formal grammar defines – Strings that belong to language • Formal languages with formal semantics generates rules for semantic specifications of programming languages Automaton • An automaton ( or automata in plural) is a machine that can recognize valid strings generated by a formal language . • A finite automata is a mathematical model of a finite state machine (FSM), an abstract model under which all modern computers are built. Automaton • A FSM is a machine that consists of a set of finite states and a transition table. • The FSM can be in any one of the states and can transit from one state to another based on a series of rules given by a transition function. Example What does this machine represents? Describe the kind of strings it will accept. Exercise • Draw a FSM that accepts any string with even number of A’s. Assume the alphabet is {A,B} Build a FSM • Stream: “I love cats and more cats and big cats ” • Pattern: “cat” Regular Expressions Regex versus FSM • A regular expressions and FSM’s are equivalent concepts. • Regular expression is a pattern that can be recognized by a FSM. • Regex is an example of how good theory leads to good programs Regular Expression • regex defines a class of patterns – Patterns that ends with a “*” • Regex utilities in unix – grep , awk , sed • Applications – Pattern matching (DNA) – Web searches Regex Engine • A software that can process a string to find regex matches.