Personal Reflections, and Implications for Replication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diana Davies Photograph Collection Finding Aid

Diana Davies Photograph Collection Finding Aid Collection summary Prepared by Stephanie Smith, Joyce Capper, Jillian Foley, and Meaghan McCarthy 2004-2005. Creator: Diana Davies Title: The Diana Davies Photograph Collection Extent: 8 binders containing contact sheets, slides, and prints; 7 boxes (8.5”x10.75”x2.5”) of 35 mm negatives; 2 binders of 35 mm and 120 format negatives; and 1 box of 11 oversize prints. Abstract: Original photographs, negatives, and color slides taken by Diana Davies. Date span: 1963-present. Bulk dates: Newport Folk Festival, 1963-1969, 1987, 1992; Philadelphia Folk Festival, 1967-1968, 1987. Provenance The Smithsonian Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections acquired portions of the Diana Davies Photograph Collection in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when Ms. Davies photographed for the Festival of American Folklife. More materials came to the Archives circa 1989 or 1990. Archivist Stephanie Smith visited her in 1998 and 2004, and brought back additional materials which Ms. Davies wanted to donate to the Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives. In a letter dated 12 March 2002, Ms. Davies gave full discretion to the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage to grant permission for both internal and external use of her photographs, with the proviso that her work be credited “photo by Diana Davies.” Restrictions Permission for the duplication or publication of items in the Diana Davies Photograph Collection must be obtained from the Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections. Consult the archivists for further information. Scope and Content Note The Davies photographs already held by the Rinzler Archives have been supplemented by two more recent donations (1998 and 2004) of additional photographs (contact sheets, prints, and slides) of the Newport Folk Festival, the Philadelphia Folk Festival, the Poor People's March on Washington, the Civil Rights Movement, the Georgia Sea Islands, and miscellaneous personalities of the American folk revival. -

Remni June 26

remembrance ni Lavender blooms at this time of year at Bouzincourt Ridge Cemetery this time of year RAF WW2 veteran enabled The Ports to do the double Jim Kerr was educated at the Model Primary School, Enniskillen and at Portora Royal. His first job was as an Page 1 accounts clerk with the local firm of T.P. Topping. When war broke out, Jim and six of his friends didn’t follow the deep-rooted Fermanagh tradition of joining the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers or the Royal Inniskilling Dragoon Guards – they plumped instead for the RAF, where he served from 1940 until he was demobbed in 1947. After training in England, Jim was posted to the Middle East and Africa. The ship convoy taking him to his posting in North Africa with the Germans in command of the Mediterranean, and an ever-present threat of U-boats, had to sail round South Africa to the Suez Canal. As a leading aircraftman, he was stationed in Alexandria and Egypt, and they were involved in various battles, until the war ended. His service continued back home in Aldergrove and dismantling the flying boats back in Killadeas, Fermanagh. He ended his RAF service in France. Jim had sad memories of the war, losing many friends in action, and he vividly remembered the day when he witnessed an RAF transport plane crash at Lydda Airport, with the loss of 150 souls. After the war, Jim Kerr took up employment as a clerical officer in the Fermanagh County Surveyor’s Office in Enniskillen. With his typically caring attitude, he involved himself in voluntary welfare work in the area, with ex-service personnel. -

Simple Minds

MERCOLEDì 12 FEBBRAIO 2020 I Simple Minds celebrano 40 anni di carriera con un colossale tour mondiale, che li porterà anche in Italia per 5 show in luoghi altrettanto iconici: al Pistoia Blues l'11 luglio, alla Cavea dell'Auditorium Parco della Simple Minds: la band festeggia Musica in Roma il 15, al Teatro D'Annunzio per Pescara Jazz e Songs il 16, 40 anni di hit con 5 grandi concerti al Teatro Antico di Taormina il 18 e infine all'Arena di Verona martedì 4 in Italia agosto, per un concerto che si preannuncia davvero memorabile: infatti la band torna ad esibirsi qui trent'anni dopo la sua prima e unica volta precedente, quando, durante il tour di "Street Fighting Years", la serata fu così indimenticabile da essere immortalata per il DVD "Seen The Lights". ANTONIO GALLUZZO Il "40 Years of HITS Tour 2020", oltre 60 date attraverso 14 Paesi solo nella prima parte in Europa, debutta il prossimo 28 febbraio in Norvegia. L'annuncio di un tour celebrativo per la band fondata e guidata da 40 anni da Jim Kerr e Charlie Burchill segue l'uscita di "40: The Best Of - 1979-2019", una raccolta che ripercorre i quaranta anni di carriera della band che ha letteralmente rivoluzionato la musica a partire dagli [email protected] anni '80, con l'aggiunta di una traccia inedita: una cover di 'For One SPETTACOLINEWS.IT Night Only' di King Creosote. Dall'esordio con Life In A Day del 1979 i Simple Minds sono diventati fra le più popolari icone della musica del nostro tempo con canzoni entrate nella storia come New Gold Dream, Up On The Catwalk, Speed Your Love To Me, Waterfront, Glittering Prize, Don't You (Forget About Me), Alive and Kicking, Sanctify Yourself, Belfast Child, She's a River, Mandela Day, per citarne solo alcune. -

ARET(I) JACKSON FIVE, "LOOKIN' THROUGH the WIN- (Pundit,BMI)

DEDICATED TO THE NEEDS OF THE MUSIC/RECORD INDUSTRY ONE DOLLAR eoo, MAY27, 1972 ciif , WHO IN THE WORLD 04, Southern Gentleman Sonny James, s. - t' 3 0 4 Left, Has Signed A Long -Term 4 34' o Contract With Columbia Records, ti 47,27(. 4 Where, No Doubt, He Will Add 41 To His String Of 28 Consecutive Number One Country Singles. On Right Is Columbia President Clive Davis, Who Flew To Nashville To Announce The Signing. For More Details, Turn To Page 3. HITS T HA FRANKLIN,"ALLTHE KING'S HORSES." cg CANDI STATON, "IN THE GHETTO."(Screen 1.11ARET(i) JACKSON FIVE, "LOOKIN' THROUGH THE WIN- (Pundit,BMI). The latest from the Gems-Columbia/ElvisPresley,BMI). DOWS." The Jacksons,firmlyentrenchedin O undisputedQueenofSoul isas Pa Even though this Mac Davis -penned althe minds of the public, consistently come up different from "Day Dreaming" as w songishardly anoldie,theper- 'elwith winning efforts. Huge sales must be ex- that was from her earlier works. An - formance here is convincing enough pected,sincethisgiftedfamily alwaysde- co other assured smash. Atlantic 2883. tomake ithappenagain.Fame livers."LittleBittyPrettyOne"included. 91000 (UA). Motown M750L. NILSSON, "COCONUT." (Blackwood, BMI). Follow- FLASH, "SMALL BEGINNINGS."(Colgems/Black- THE BEACH BOYS, "PET SOUNDS/CARL AND THE upto "JumpInto The Fire"isa claw, ASCAP). Flash, very much like PASSIONS -SOTOUGH." Applausetoeveryone whimsical story from the outstand- Yes,should makeiton AM just concerned for this specially -priced doubleal- ing"Nilsson Schmilsson."Terrific, as they will on FM. This should be bum. "Pet Sounds," recordedin1966, was a and commercial enoughtogoall thefirsthitfromthebestnew recent purchase from Capitol. -

Central Florida Future, Vol. 18 No. 40, April 3, 1986

University of Central Florida STARS Central Florida Future University Archives 4-3-1986 Central Florida Future, Vol. 18 No. 40, April 3, 1986 Part of the Mass Communication Commons, Organizational Communication Commons, Publishing Commons, and the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Central Florida Future by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation "Central Florida Future, Vol. 18 No. 40, April 3, 1986" (1986). Central Florida Future. 622. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/centralfloridafuture/622 • he Central Florida Future Volume 18 Number 40 University of Central Florida/Orlando Thursday April 3, 1986 Moorehead . T_HE STUDENT GOVERNMENT VOTE not a hawk or a dove by Mike Carr CENTRAL FLORIDA FUTURE A former Iranian hostage * . * *· * * * . * . wants UCF students to play his terrorist video game . • The object of Moorhead Kennedy's game isn't to blast the bad guys; it's to understand them. "If you use excessive force or give into the terrorists' demands, The Central Florida • the game Future conducted an tilts," exit poll of voters in Kennady this week's election. said. Subjects were asked Crisis, the college of their the major and who they Kennedy computer voted for. The survey game, won't come on the market for another year, but was an informal one Kennedy was delivering its and is not meant to ·foreign ·policy message while represent a scientific, speaking at the student random sampling of center and engineering the students who auditorium on Tuesday. -

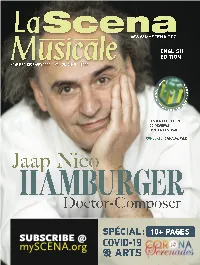

Myscena.Org Sm26-3 EN P02 ADS Classica Sm23-5 BI Pxx 2020-11-03 8:23 AM Page 1

SUBSCRIBE @ mySCENA.org sm26-3_EN_p02_ADS_classica_sm23-5_BI_pXX 2020-11-03 8:23 AM Page 1 From Beethoven to Bowie encore edition December 12 to 20 2020 indoor 15 concerts festivalclassica.com sm26-3_EN_p03_ADS_Ofra_LMMC_sm23-5_BI_pXX 2020-11-03 1:18 AM Page 1 e/th 129 saison/season 2020 /2021 Automne / Fall BLAKE POULIOT 15 nov. 2020 / Nov.ANNULÉ 15, 2020 violon / violin CANCELLED NEW ORFORD STRING QUARTET 6 déc. 2020 / Dec. 6, 2020 avec / with JAMES EHNES violon et alto / violin and viola CHARLES RICHARD HAMELIN Blake Pouliot James Ehnes Charles Richard Hamelin ©Jeff Fasano ©Benjamin Ealovega ©Elizabeth Delage piano COMPLET SOLD OUT LMMC 1980, rue Sherbrooke O. , Bureau 260 , Montréal H3H 1E8 514 932-6796 www.lmmc.ca [email protected] New Orford String Quartet©Sian Richards sm26-3_EN_p04_ADS_udm_OCM_effendi_sm23-5_BI_pXX 2020-11-03 8:28 AM Page 1 SEASON PRESENTER ORCHESTRE CLASSIQUE DE MONTRÉAL IN THE ABSENCE OF A LIVE CONCERT, GET THE LATEST 2019-2020 ALBUMS QUEBEC PREMIER FROM THE EFFENDI COLLECTION CHAMBER OPERA FOR OPTIMAL HOME LISTENING effendirecords.com NOV 20 & 21, 2020, 7:30 PM RAFAEL ZALDIVAR GENTIANE MG TRIO YVES LÉVEILLÉ HANDEL’S CONSECRATIONS WONDERLAND PHARE MESSIAH DEC 8, 2020, 7:30 PM Online broadcast: $15 SIMON LEGAULT AUGUSTE QUARTET SUPER NOVA 4 LIMINAL SPACES EXALTA CALMA 514 487-5190 | ORCHESTRE.CA THE FACULTY IS HERE FOR YOUR GOALS. musique.umontreal.ca sm26-3_EN_p05_ADS_LSM_subs_sm23-5_BI_pXX 2020-11-03 2:32 PM Page 1 ABONNEZ-VOUS! SUBSCRIBE NOW! Included English Translation Supplément de traduction française inclus -

SIMPLE MINDS Celebrating 40 Years of Hits Tour 2022

DO 17.03.2022, 20:00 Uhr | Freiburg, Musikklub/SICK-Arena DI 29.03.2022, 20:00 Uhr | Ravensburg, OberschwabenKlub SIMPLE MINDS Celebrating 40 Years Of Hits Tour 2022 Ein 40-jähriges Bühnenjubiläum gehört gebührend gefeiert – live und mit Fans! Deshalb freuen wir uns, dass es den Simple Minds gelungen ist, die komplette Tournee in einem Kraftakt auf 2022 zu schieben. Alle 15 Deutschland-Konzerte sollen nachgeholt werden, darunter Freiburg am 17.03.22 und Ravensburg am 29.03.22. Die Simple Minds planten ihre Jubiläums-Welttournee „Celebrating 40 Years Of Hits“ ursprünglich für 2020 und in einem zweiten Anlauf für 2021. Aufgrund der anhaltenden COVID-19-Pandemie konnte natürlich keines dieser Konzerte stattfinden. Tickets für die Termine aus 2020/21 behalten ihre Gültigkeit für die Tournee 2022. Die Simple Minds sind musikalische Pioniere – und das seit 40 Jahren. Sie haben die Post-Punk-Ära bestimmend geprägt, als der wütende Krach von 1977 in tausenderlei Sounds zersplitterte. Sie haben den stylischen Art-Rock von David Bowie genauso organisch in ihre Sounds übernommen wie das elektronische Disco-Geplucker von Donna Summer. Sie haben sich und ihre Musik vielfach gedreht, verwandelt und erneuert. Die Simple Minds wurden zu einer der größten Bands des Planeten, standen mit dem Überhit „Don’t You (Forget About Me)“ an der Spitze der US-Charts und mit fünf ihrer Alben in Großbritannien auf Platz eins. Sie haben 60 Millionen Platten verkauft und die größten Stadien der Welt bis auf den letzten Platz ausverkauft. Oder um es mit den Worten von -

Remni Life Stories 1

remembrance ni World War 2 Life stories Church bell ringer awarded DSM for his part in naval action Petty Officer Norman Matson was a keen bellringer and was a member of St. Thomas's Bell-Ringers Society on Belfast’s Lisburn Road. On the morning of Sunday, 15th November 1940, across the United Kingdom a "firing peal" of bells was rung in honour of the first offensive victory by the Allied forces. Norman who was home on leave at the time, was given the honour of the Society by being assigned the biggest bell, the tenor. In 1940 Norman was serving on board HMS Carnarvon Castle. Built by Harland and Wolff, the Carnarvon… Page !1 Bellringers of St Thomas’ Church, Belfast who took part in the Victory Peel. Norman Matson is to the extreme right. Photo - Larne Times, 19/11/1942. …Castle was a passenger ship operated by the Union- Castle Mail line. Requisitioned by the Admiralty in September 1939 while in Cape Town, she was converted into an armed merchant cruiser and commissioned in October 1939. On the 5th December 1940, while off the coast of Brazil, she encountered the German auxiliary cruiser Thor. In a five- hour running battle with her the Carnarvon Castle suffered Page !2 heavy damage, sustaining 27 hits causing 4 dead and 27 wounded. For his part in the action Norman was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal. Carnarvon Castle put into Montevideo for repairs. She was repaired with steel plate reportedly salvaged from the German cruiser Admiral Graf Spee. Norman Leslie Matson was born in Belfast on the 17th November 1903. -

PP Bliss, His Life & Life Work

www.WholesomeWords.org edition 2010 P. P. Bliss, His Life & Life Work Edited by Major Whittle and W. Guest Contents Introduction by D. L. Moody Prefactory by William Guest Chapter 1 Mr. Bliss's Ancestry—His Father, John Bliss—His Early Days—Love for Music— First Sight of a Piano— Connection with the Church—Influence of a Pious Father's Example—First Musical Instruction—W. B. Bradbury; and Mr. Bliss's Tribute to his Memory. Chapter 2 Teaching in Rome, Pa.—Acquaintance with and Marriage to Lucy Young—Her Character— Working upon the Farm and Teaching Music—Letter from Rev. Darwin Cook—Mr. Bliss in his new Home—His Father 's Last Days —"Grandfather's Bible." Chapter 3 Mr. Bliss's First Musical Composition—Twelve Years' Song Writing—Removes to Chicago—First Meeting with Mr. Moody—Memorial by Dr. Goodwin—Mr. Bliss as a Clorister, and Sunday School Superintendent. Chapter 4 His Evangelistic Work—Mr. Moody's Appeal to Mr. Bliss— The Turning Point—An Experimental Meeting at Waukegan—Bliss's Consecration of Himself to God's Service—His Faith and Self-denial—Working for the Young—An Incident—His Methods of Teaching. Chapter 5 Mr. Bliss as a Composer and Author—His first Sunday- school Hymns—His Habits and Manner of Writing— Incidents that suggested his Hymns—Letter from Mr. Sankey—Last Hymn he Wrote. Chapter 6 The Work of an Evangelist—Gospel Meetings—Visit to Kenesaw Mountain—At Chicago—At Home—Philadelphia Exhibition—Night Scene—Dr. Vincent's Tribute. Chapter 7 The Last Earthly Labours—In Chicago with Evangelists— In Michigan—Impressive Scenes in Farwell Hall, Chicago. -

A Metaphorical Analysis of John Mayer's Album Continuum By

Stop this Train: A Metaphorical Analysis of John Mayer’s Album Continuum by Joshua Beal A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Major Subject: Communication West Texas A&M University Canyon, Texas August 2017 ABSTRACT John Mayer’s album Continuum is his third studio album and includes some of his best work. This analysis used a five-step metaphorical approach, as referenced to Ivie (1987), to understand the rhetorical invention of Mayer’s album Continuum and to interpret the metaphorical concepts employed by Mayer. This analysis discovered six tenors: Peace, Spirit, Darkness, Hope, Violence, and Cruelty and their accompanying vehicles. Rhetorical techniques in Mayer’s lyrics can be associated to references to nature, contrasting abstract with concrete terms, and the use of opposites (God/Devil terms). Continuum is an album that incorporates the trials and tribulations of romantic relationships using a combination of blues, soul, and contemporary pop music to underscore the lyrics. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my thesis chair, Dr. Trudy Hanson, and her constant efforts to guide me through an adventure that I will never forget. This experience is as rewarding as it is special to me and I couldn’t have done this without you. I would also like to express my appreciation to the members of my committee, Dr. Jessica Mallard, and Randy Ray. My experience as a graduate student is an experience that I will cherish, and the memories I have collected are priceless. I would also like to express my gratitude to my parents, Raymond and Mary Laura Beal, and my brother, Austin Beal, for their continued support throughout this journey. -

Billy Joel's Turn and Return to Classical Music Jie Fang Goh, MM

ABSTRACT Fantasies and Delusions: Billy Joel’s Turn and Return to Classical Music Jie Fang Goh, M.M. Mentor: Jean A. Boyd, Ph.D. In 2001, the release of Fantasies and Delusions officially announced Billy Joel’s remarkable career transition from popular songwriting to classical instrumental music composition. Representing Joel’s eclectic aesthetic that transcends genre, this album features a series of ten solo piano pieces that evoke a variety of musical styles, especially those coming from the Romantic tradition. A collaborative effort with classical pianist Hyung-ki Joo, Joel has mentioned that Fantasies and Delusions is the album closest to his heart and spirit. However, compared to Joel’s popular works, it has barely received any scholarly attention. Given this gap in musicological work on the album, this thesis focuses on the album’s content, creative process, and connection with Billy Joel’s life, career, and artistic identity. Through this thesis, I argue that Fantasies and Delusions is reflective of Joel’s artistic identity as an eclectic composer, a melodist, a Romantic, and a Piano Man. Fantasies and Delusions: Billy Joel's Turn and Return to Classical Music by Jie Fang Goh, B.M. A Thesis Approved by the School of Music Gary C. Mortenson, D.M.A., Dean Laurel E. Zeiss, Ph.D., Graduate Program Director Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music Approved by the Thesis Committee Jean A. Boyd, Ph.D., Chairperson Alfredo Colman, Ph.D. Horace J. Maxile, Jr., Ph.D. -

Diana Davies Photographs, 1963-2009

Diana Davies photographs, 1963-2009 Stephanie Smith, Joyce Capper, Jillian Foley, and Meaghan McCarthy 2004-2005 Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage 600 Maryland Ave SW Washington, D.C. [email protected] https://www.folklife.si.edu/archive/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Biographical/Historical note.............................................................................................. 2 General note.................................................................................................................... 3 Arrangement note............................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 6 Series 1: Newport Folk Festival, 1964-1992, undated............................................. 6 Series 2: Philadelphia Folk Festival, 1967 - 1987.................................................. 46 Series 3: Broadside