Rave Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Course Syllabus Live-Performance Disc Jockey Techniques 3 Credits

Course Syllabus Live-Performance Disc Jockey Techniques 3 Credits MUC135, Section 33575 Scottsdale Community College, Department of Music Fall 2015 (September 1 to December 18, 2015) Tuesday Evenings 6:30 PM - 9:10 PM (Room MB-136) Instructor: Rob Wegner, B.S., M.A. ([email protected] or [email protected]); Cell: 480-695-6270 Office Hours: Monday’s 6:00 - 7:30PM (Room MB-139) Recommended Text: How to DJ Right: The Art and Science of Playing Records by Bill Brewster and Frank Broughton (Grove Press, 2003). ISBN: 0-8021- 3995-7 Groove Music: The Art and Culture of the Hip-Hop DJ by Mark Katz (Oxford University Press, 2012). ISBN-10: 0195331125 Recommended DVD: Scratch: A Film by Doug Prey by Doug Prey (Palm Pictures, 2001). Required Gear: Headphones (for labs) Additional Suggested Reading: Off the Record by Doug Shannon (1982), Pacesetter Publishing House. Last Night A DJ Saved My Life, The History of the Disc Jockey by Bill Brewster & Frank Broughton (2000), Grove Press. On The Record: The Scratch DJ Academy Guide by Phil White & Luke Crisell (2009), St. Martin’s Griffin. Looking for the Perfect Beat by Kurt B. Reighley (2000), Pocket Books. How to Be a DJ by Chuck Fresh (2001), Brevard Marketing. DJ Culture by Ulf Poschardt (1995), Quartet Books Limited. The Mobile DJ Handbook, 2nd Edition by Stacy Zemon (2003), Focal Press. Turntable Basics by Stephen Webber (2000), Berklee Press. Course Objectives Upon successful completion of this course, you should be able to: explain the historical innovations that led to the evolution of -

The Indigent's Right to Counsel in Civil Cases

The Indigent's Right To Counsel In Civil Cases A man whose life or liberty is jeopardized by a felony charge has a constitutional right to a lawyer.' When his property - is at stake, in a civil case, he may have a lawyer too-but only if he can afford to hire one.3 This gap between the rights of poor criminal defendants and poor civil litigants was left undisturbed by the Supreme Court in October 1966, when it denied certiorari in the case of Sandoval v. Rattikin.4 Matias and Teresa Sandoval, an indigent and illiterate Texas couple, had sought to reverse a civil judgment on the ground that the state's failure to appoiiit counsel for them violated the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment. In a trespasst9-try-title action, the Sandovals had lost the two-room house in which they ha-lived since 1945 with their nine children. Two weeks before thek.trial, thei lawyer withdrew because they could not pay his fee, so they turned to the Nueces County legal aid attorney. He spoke only English and did'no attempt to confer with his clients, who spoke only Spanish. His perfunctory preparation did not inform him that the "deed" on which plaintiff based his claim to the Sandovals' land was actually a mortgage, which under Texas homestead law could not confer title.5 As the Sandovals' plight indicates, the actual concerns of the poor do not reflect the law's sharp distinction between civil and criminal liti- gants. Poverty only magnifies the importance of protecting one's prop- erty from seizure by legal process. -

Authenticity in Electronic Dance Music in Serbia at the Turn of the Centuries

The Other by Itself: Authenticity in electronic dance music in Serbia at the turn of the centuries Inaugural dissertation submitted to attain the academic degree of Dr phil., to Department 07 – History and Cultural Studies at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz Irina Maksimović Belgrade Mainz 2016 Supervisor: Co-supervisor: Date of oral examination: May 10th 2017 Abstract Electronic dance music (shortly EDM) in Serbia was an authentic phenomenon of popular culture whose development went hand in hand with a socio-political situation in the country during the 1990s. After the disintegration of Yugoslavia in 1991 to the moment of the official end of communism in 2000, Serbia was experiencing turbulent situations. On one hand, it was one of the most difficult periods in contemporary history of the country. On the other – it was one of the most original. In that period, EDM officially made its entrance upon the stage of popular culture and began shaping the new scene. My explanation sheds light on the fact that a specific space and a particular time allow the authenticity of transposing a certain phenomenon from one context to another. Transposition of worldwide EDM culture in local environment in Serbia resulted in scene development during the 1990s, interesting DJ tracks and live performances. The other authenticity is the concept that led me to research. This concept is mostly inspired by the book “Death of the Image” by philosopher Milorad Belančić, who says that the image today is moved to the level of new screen and digital spaces. The other authenticity offers another interpretation of a work, or an event, while the criterion by which certain phenomena, based on pre-existing material can be noted is to be different, to stand out by their specificity in a new context. -

Turntablism and Audio Art Study 2009

TURNTABLISM AND AUDIO ART STUDY 2009 May 2009 Radio Policy Broadcasting Directorate CRTC Catalogue No. BC92-71/2009E-PDF ISBN # 978-1-100-13186-3 Contents SUMMARY 1 HISTORY 1.1-Defintion: Turntablism 1.2-A Brief History of DJ Mixing 1.3-Evolution to Turntablism 1.4-Definition: Audio Art 1.5-Continuum: Overlapping definitions for DJs, Turntablists, and Audio Artists 1.6-Popularity of Turntablism and Audio Art 2 BACKGROUND: Campus Radio Policy Reviews, 1999-2000 3 SURVEY 2008 3.1-Method 3.2-Results: Patterns/Trends 3.3-Examples: Pre-recorded music 3.4-Examples: Live performance 4 SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM 4.1-Difficulty with using MAPL System to determine Canadian status 4.2- Canadian Content Regulations and turntablism/audio art CONCLUSION SUMMARY Turntablism and audio art are becoming more common forms of expression on community and campus stations. Turntablism refers to the use of turntables as musical instruments, essentially to alter and manipulate the sound of recorded music. Audio art refers to the arrangement of excerpts of musical selections, fragments of recorded speech, and ‘found sounds’ in unusual and original ways. The following paper outlines past and current difficulties in regulating these newer genres of music. It reports on an examination of programs from 22 community and campus stations across Canada. Given the abstract, experimental, and diverse nature of these programs, it may be difficult to incorporate them into the CRTC’s current music categories and the current MAPL system for Canadian Content. Nonetheless, turntablism and audio art reflect the diversity of Canada’s artistic community. -

1 "Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music S

"Disco Madness: Walter Gibbons and the Legacy of Turntablism and Remixology" Tim Lawrence Journal of Popular Music Studies, 20, 3, 2008, 276-329 This story begins with a skinny white DJ mixing between the breaks of obscure Motown records with the ambidextrous intensity of an octopus on speed. It closes with the same man, debilitated and virtually blind, fumbling for gospel records as he spins up eternal hope in a fading dusk. In between Walter Gibbons worked as a cutting-edge discotheque DJ and remixer who, thanks to his pioneering reel-to-reel edits and contribution to the development of the twelve-inch single, revealed the immanent synergy that ran between the dance floor, the DJ booth and the recording studio. Gibbons started to mix between the breaks of disco and funk records around the same time DJ Kool Herc began to test the technique in the Bronx, and the disco spinner was as technically precise as Grandmaster Flash, even if the spinners directed their deft handiwork to differing ends. It would make sense, then, for Gibbons to be considered alongside these and other towering figures in the pantheon of turntablism, but he died in virtual anonymity in 1994, and his groundbreaking contribution to the intersecting arts of DJing and remixology has yet to register beyond disco aficionados.1 There is nothing mysterious about Gibbons's low profile. First, he operated in a culture that has been ridiculed and reviled since the "disco sucks" backlash peaked with the symbolic detonation of 40,000 disco records in the summer of 1979. -

MEDIA KIT M K E D I a Audio SOUL PROJECT

AL MA KEEPING IT UNREAL SINCE 1991 I Z IC I F F O MEDIA KIT ASP AUDIO I T SOUL PROJECT M K E D I A AUDIO SOUL PROJECT A prolific producer, Mazi Namvar has written Recordings, Cates & dPL’s “Through The or remixed over 200 records in 15 years Weekend” on OM Records, Alexander time. He works under several pseudonyms Maier’s “Sahara Rain” on Mood Music, Nick the most popular of which is Audio Soul and Danny Chatelain’s “Sube Conmigo” Project. Current original ASP releases have on NRK, Chaim’s “C Factor” on Missive appeared on Dessous, Systematic, Circle Recordings and Matthias Vogt’s “Roofs” on Music, SAW, Mood Music and Ovum. Fresh Meat. His latest production “Traditionalist” for Systematic recordings was featured on that A DJ for 18 years, Mazi has visited clubs label’s 5 vinyl box set entitled “5YSYST” like Fabric in London, Crystal in Istanbul, Q and reached the top 10 Deep House chart in Zürich, Avalon in Los Angeles, Masai in on Beatport.com. His music has recently Varna, Level in Bahrain, Red Light in Paris appeared on compilations such as Loco and Simoon in Tokyo. He still finds time to Dice “The Lab01” on NRK Music, Darren play in Chicago, DJ’ing or performing live Emerson’s “Bogota GU36” on Global at local venues like Spy Bar, Moonshine, Underground, Ralph Lawson’s “Fabric 33” Zentra, Vision and Smart Bar. mix, Sander Kleinenberg’s edition of the famous “This Is” Renaissance series and on As an A & R executive, Mazi presides over the 9th volume of the “KM5 Ibiza” series on his label Fresh Meat Records which he co- Belgium’s impeccable NEWS label. -

Electronically Filed Supreme Court SCAP-13-0000029 21-DEC-2015 08:48 AM

*** NOT FOR PUBLICATION IN WEST’S HAWAI#I REPORTS AND PACIFIC REPORTER *** Electronically Filed Supreme Court SCAP-13-0000029 21-DEC-2015 08:48 AM SCAP-13-0000029 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF HAWAI#I STATE OF HAWAI#I, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. FAALAGA TOMA, Defendant-Appellant. APPEAL FROM THE CIRCUIT COURT OF THE FIRST CIRCUIT (CAAP-13-0000029; CR. NO. 11-1-0452) MEMORANDUM OPINION (By: Recktenwald, C.J., Nakayama, McKenna, and Pollack, JJ., and Circuit Judge Nacino, in place of Wilson, J., recused) Part I (By: Nakayama, J., with whom Recktenwald, C.J., and Circuit Judge Nacino, join, and Pollack, J., dissenting separately, with whom McKenna, J., joins) Part II (By: Pollack, J., with whom Recktenwald, C.J., and McKenna, J., join, and Nakayama, J., dissenting separately, with whom Circuit Judge Nacino J., joins) INTRODUCTION This appeal arises out of defendant-appellant Faalaga Toma’s (Toma) conviction of assault in the second degree in the Circuit Court of the First Circuit (circuit court). Toma was *** NOT FOR PUBLICATION IN WEST’S HAWAI#I REPORTS AND PACIFIC REPORTER *** charged with assault in the second degree on April 5, 2011. At the end of trial, the circuit court allowed the jury to be instructed with accomplice liability over the defense’s objection, and the jury found Toma guilty as an accomplice to the assault. On appeal, Toma argues that the circuit court erred in giving the complicity instruction because the felony information charged him as a principal and did not give him adequate notice that he could be convicted as an accomplice. -

Microsoft Office Outlook

Eliot I. Bernstein Full Name: Above and Beyond First Name: Above and Beyond Job Title: James Grant - Manager Business: 44 20 8742 4950 E-mail: enquiries Categories: call ultrafest 09 20090319 cmb sent email to 20090319 cmb per recept not manager James Grant Media Ltd 94 Strand On The Green Chiswick London W4 3NN tel: 020 8742 4950 fax: 020 8742 4951 email: enquiries James Grant Music Management was formed in the early part of 2005 by Nick Worsley and Simon Hargreaves and is a joint venture with long established TV Management Company James Grant Media. Heading up the company are two former Sony Music Entertainment Executives - Nick Worsley who was Head of Radio Promotions and Simon Hargreaves who was Head Of Press and Publicity. Bringing together over 20 years of music industry experience across both Major labels and the Independent sector - James Grant Music delivers a fresh and extremely potent force in the Music Business and is already breaking new ground in the Music Management arena. 1 Eliot I. Bernstein Full Name: Alina First Name: Alina E-mail: [email protected] E-mail Display As: Alina ([email protected]) Categories: call ultrafest 09 20090319 cmb sent email to the email above AFFILIATION: Sequence Production BOOKING CONTACT: [email protected] BIOGRAPHY Alina Sequence career has begun in 1994 when it has started to work as the assistant to the arranger in a sound studio. Greater support was rendered by Andrey Ivanov (Triplex), having given many useful knowledge in the field of electronic tools, becoming first producer Alina. In 1997 Alina Sequence bases under the beginning a promo-label " Sequence Records " which is engaged in producing of young electronic musicians, and also release of releases of Russian electronic music. -

Automation: from Consoles to Daws

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 12-2016 Automation: From Consoles to DAWs Christian Ekeke California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all Part of the Music Education Commons Recommended Citation Ekeke, Christian, "Automation: From Consoles to DAWs" (2016). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 41. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes_all/41 This Capstone Project (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects and Master's Theses at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Christian Ekeke 12/19/16 Capstone 2 Dr. Lanier Sammons Automation: From Consoles to DAWs Since the beginning of modern music there has always been a need to implement movement into a mix. Whether it is bringing down dynamics for a classic fade out or a filter sweep slowly building into a chorus, dynamic activity in a song has always been pleasing to the average music listeners. The process that makes these mixing techniques possible is automation. Before I get into details about automation in regards to mixing I will explain common ways automation is used. Automation in a nutshell is the use of various techniques, method, and system of operating or controlling a process by highly automatic means generally through electronic devices. In music however, automation is simply the use of a combination of multiple control devices to alter parameters in real time while a mix is being played. -

Acid Pro a Guide for the Beginner, by Alex C for Boot Camp Clique

Acid Pro A Guide for the beginner, by Alex C for Boot Camp Clique 1 Where can I get Acid or Acid Pro? That’s an excellent question, and if you’ve not got Acid yet – one you should most definitely be asking! A quick Google search for “acid pro” will give you a few sites, and most importantly www.sonicfoundry.com which is the company who used to make Acid. Since they were taken over by Sony however, you’re not going to get far with that link. Where you should really go is to http://www.sonymediasoftware.com where you can click on ‘software’ and then ‘ACID’ - taking you to precisely the right place. Sony are now the company which manufacture and develop Acid, and at the time of writing this article they are on version 6. Acid Pro 6. Now, Sony will let you download a free trial, to get your fix, but you should really take the plunge and purchase this masterpiece. If you’re serious about music production – and in particular bootlegs and mash-ups, then it’s worth forking out the $374.96 that they’re charging on the site. Following that, you can relax in the knowledge that you own a monster package for making your tunes. 2 OK, it’s installed. What now? After all the downloading, purchasing and installing gubbins – which you should be able to work out yourself (after all this isn’t a lesson on downloading software or installing such stuff) we can move on to the intro. Acid is primarily a piece of ‘sequencing’ software. -

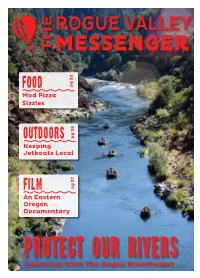

Protect Our Rivers Interview with the Rogue Riverkeeper 2

Volume 4, Issue 14 // July 6 - July 19, 2017 FOOD pg 22 Mod Pizza Sizzles OUTDOORS pg 26 Keeping Jetboats Local FILM pg 27 An Eastern Oregon Documentary Protect our rivers Interview With The Rogue Riverkeeper 2 / WWW.ROGUEVALLEYMESSENGER.COM SUMMER EXHIBITIONS Tofer Chin: 8 Amir H. Fallah: Unknown Voyage Ryan Schneider: Mojave Masks Liz Shepherd: East-West: Two Streams Merging Wednesday, June 14 through Saturday, September 9, 2017 The Summer exhibitions are funded in part by a generous donation from Judy Shih and Joel Axelrod. MUSEUM EVENTS Tuesday Tours: IMAGES (LEFT TO RIGHT, TOP TO BOTTOM, DETAILS): Tofer Chin, Overlap No. 3, 2016, Acrylic on canvas, 48 x 34” Free Docent-led Tours of the Exhibitions Amir H. Fallah, Unknown Voyage, 2015, Acrylic, colored pencil and collage on paper mounted on canvas, 48 x 36” Ryan Schneider, Many Headed Owl, 2016, Oil on canvas, 60 x 48” Liz Shepherd, Mount Shasta at Dawn, 2012, Watercolor on riches paper, 19.5 x 27.5” Tuesdays at 12:30 pm MUSEUM HOURS: MONDAY – SATURDAY, 10 AM TO 4 PM • FREE AND OPEN TO THE PUBLIC mailing: 1250 Siskiyou Boulevard • gps: 555 Indiana Street Ashland, Oregon 97520 541-552-6245 • email: [email protected] web: sma.sou.edu • social: @schneidermoa PARKING: From Indiana Street, turn left into the metered lot between Frances Lane and Indiana St. There is also limited parking behind the Museum. JULY 6 – JULY 19, 2017 / THE ROGUE VALLEY MESSENGER / 3 The Rogue Valley Messenger PO Box 8069 | Medford, OR 97501 CONTENTS 541-708-5688 page page roguevalleymessenger.com FEATURE FOOD [email protected] Rivers are the lifeblood Mod Pizza is a THE BUSINESS END OF THINGS that flows throughout Seattle-based chain. -

Richie Hawtin Has Always Been at the Leading Edge of Innovation in All Aspects of Electronic Music. Now More Than Ever, He's S

RICHIE HAWTIN WordsRichie Richie Hawtin and Thomas H Green Photos www.alexanderkoch.com 0123456789 Hawtin 0123456789 new horizons Richie Hawtin has always been at the leading edge of innovation in all aspects R e of electronic music. Now more than ever, he’s searching for fresh horizons and new MM joe pli worlds to conquer. Who better to launch the first ever Mixmag Live? [[1L]] MARCH 2012 RICHIE HAWTIN Plastikman @ Brixton Academy, London from his lively blue eyes. He’s in dance music’s warlock, derive from his family’s move on November premier league these days, an immediately 14 1979 from the Northamptonshire village of recognisable name atop bills at clubs, raves and Middleton Cheney to LaSalle, Ontario, Canada, festivals and someone who is these days recognised when he was nine years old. even in the least likely of places. “My main memory of Middleton Cheney is a R te “I took a vacation on the coast of Morocco with strong sense of extended family, cousins, aunts, S ee my girlfriend,” he says in his relaxed Canadian uncles, a very close-knit family, everyone getting M accent, “walking though streets without pavements, together regularly,” he says. “That’s why the Canadian eule so far away from our world – and someone was like, move was such a big change: becoming isolated, M ‘Are you Richie Hawtin? Can I get your autograph?’.” introverted. The ‘DJ Richie Hawtin’ aspect of me Ann De : He laughs – “But it’s alright, people who come up are reflects what I remember of myself before I went S long term fans, not ‘I know that guy’s face from a to Canada: having all these people around, being boot D 0123456789 n 0123456789 A magazine.’ It’s a nicer sort of fame.” in elementary school, the cool kid in class who CH As Richie Hawtin he is the DJ who brings techno everyone talked to.