Effect and Implementation Experience of Intensive Adherence Counseling in a Public Hiv Care Center in Uganda: a Mixed-Methods Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program of the 4Th Scientific Conference

Makerere University College of Health Sciences Program for the 7th Annual Scientific Conference 20th – 22nd September 2011; Speke Resort Munyonyo Kampala, Uganda 20th SEPTEMBER 2011 Abstract No. Time Presentation 8.00-8.30 Arrival and registration PLENARY Chair: Dr Rhoda Wanyenze; Co-Chair: Dr. Freddie Bwanga 8.30 - 9.00 Key note address – All for Health – One Health: Dr. Jane Aceng Director General MOH PLENARY Health Systems, Health Policy & Healthcare Chair: Prof Fredrick Wabwire-Mangen; Co-Chair: Prof. David Guwatudde PP1001_20 9.00-9.10 Health Systems, Governance and Health Outcome: Dr. Freddie Ssengoba PP1002_20 9.10-9.20 Challenges and Future Systems in Uganda to Ensure Delivery of Quality Care: Dr. Robert Basaza PP1003_20 9.20-9.30 Transforming Education to Strengthen Health Systems in an Inter-department World: Prof. David Serwadda 9.30-9:40 DISCUSSION PP1004_20 9:40-9:50 Role of Cultural Institutions in Healthcare Delivery, Disease Prevention and Health Promotion: Dr. Nelson Kawalya PP1005_20 9:50-10:00 Impact of Private for Profit Institutions in Healthcare Delivery and Health Systems Strengthening: Dr. Ian Clarke PP1006_20 10:00-10:10 HIV/AIDS programming through District based technical assistance programme: Experience from STAR-EC: Dr. Samson Kironde 10:10-10:20 DISCUSSION 10:20-10:50 TEA BREAK OFFICIAL OPENING CEREMONY: MC – Prof. Harriet Mayanja; Co-MC: Mr. Gerald Makumbi 10:50-10.55 Welcome remarks by Chair, 7ASC Organising Committee MakCHS: Dr. Freddie Bwanga 10.55-11.10 Announcement of the Bill & Melinda Gates Research Grant for Africa: Dr. Wong 11.10-11.10 Remarks on Translating Research into Policy and Healthcare Delivery by Chair, Research College of Health Sciences Makerere University: Prof. -

Lab Resources

Institution: Makerere University College of Health Sciences [MakCHS] and Makerere School of Public Health [MakSPH] Kampala, Uganda http://chs.mak.ac.ug/ Contact: Jacinta Oyella [MakCHS] Physician [email protected] [email protected] Dr. Rhoda Wanyenze [MakSPH] Director, MakSPH Fellowship Program [email protected] & Dr. Professor William Bazeyo Dean, MakSPH [email protected] LAB RESOURCES Please describe the laboratory facilities available in your research institute, including the items listed below (if applicable): Lab space and equipment (general): Adequate BSL-2 lab space and equipment: Adequate BSL-3 lab space and equipment: Provided by CDC through Makerere- Mbarara joint AIDS program; Rakai Health Science Program (RHSP) Flow cytometry equipment: Provided by CDC through Makerere- Mbarara joint AIDS program; RHSP Other: Viral load provided by Infectious Diseases Institute/Kampala at a cost; RHSP Please list the research groups in your institute, including the size and areas of expertise for each group: Infectious Diseases Institute/Kampala: HIV/AIDS research MJAP: AIDS research Baylor College: HIV/AIDS Case Western Reserve University: TB program Makerere University School of Pubic Health: Monitoring and Evaluation Technical Assistance (UCSF) and CDC Fellowship Program, and collaboration with Rakai Health Sciences Program (RHSP) BIOLOGICAL SPECIMEN REPOSITORY Please describe the biological specimens stored at your institute Blood Does your institute have a database of stored samples: Yes Please provide details on methods -

Conference Programme

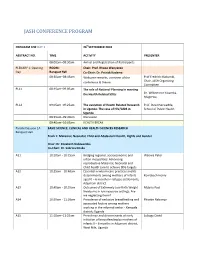

JASH CONFERENCE PROGRAM PROGRAM FOR DAY 1 26thSEPTEMBER 2018 ABSTRACT NO. TIME ACTIVITY PRESENTER 08:00am–08:30am Arrival and Registration of Participants PLENARY 1: Opening ROOM: Chair: Prof. Rhoda Wanyenze Day Banquet Hall Co-Chair: Dr. Patrick Kadama 08:30am–08:45am Welcome remarks, overview of the Prof Fredrick Makumbi, conference & theme Chair, JASH Organizing Committee PL11 08:45am–09:05am The role of National Planning in meeting the Health Related SDGs Dr. Wilberforce Kisamba- Mugerwa, PL12 09:05am–09:25am The evolution of Health Related Research Prof. David Serwadda, in Uganda: The case of HIV/AIDS in School of Public Health Uganda 09:25am–09:40am Discussion 09:40am–10:05am HEALTH BREAK Parallel Session 1A BASIC SCIENCE, CLINICAL AND HEALTH SCIENCES RESEARCH Banquet Hall Track 1: Maternal, Neonatal, Child and Adolescent Health, Rights and Gender Chair: Dr. Elizabeth Nabiwemba Co-Chair: Dr. Sabrina Kitaka A11 10:10am - 10:25am Bridging regional, socioeconomic and Waiswa Peter urban inequalities: Advancing reproductive Maternal, Neonatal and Child health care to achieve SDG targets. A12 10:25am - 10:40am Essential newborn care practices and its determinants among mothers of infants Komakech Henry aged 0 – 6 months in refugee settlements, Adjumani district A13 10:40am - 10:55am Outcomes of Extremely Low Birth Weight Mubiru Paul Newborns in low resource settings: Are we neglecting them? A14 10:55am - 11:10am Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding and Phoebe Nabunya associated factors among mothers working in the informal sector - Kampala district; Uganda A15 11:10am–11:25am Prevalence and determinants of early Lubogo David initiation of breastfeeding by mothers of infants 0 – 6 months in Adjumani district, West Nile, Uganda PROGRAM FOR DAY 1 26thSEPTEMBER 2018 ABSTRACT NO. -

Mak Research Report 2018

RESEARCH AT MAKERERE UNIVERSITY Copyright 2018 RESEARCH AT MAKERERE UNIVERSITY 3 Table of Contents MESSAGE FROM THE VICE CHANCELLOR 4 MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR, DIRECTORATE OF RESEARCH AND 6 GRADUATE TRAINING INSTITUTIONAL BACKGROUND 8 RESEARCH AT MAKERERE UNIVERSITY 10 DIRECTORATE OF RESEARCH AND GRADUATE TRAINING 16 GRADUATE TRAINING STATISTICS 18 RESEARCH FUNDING AND RESEARCH COLLABORATION AT DRGT 27 HUMAN RESOURCES AND CAPACITY BUILDING IN RESEARCH 33 HIGHLIGHTS OF RESEARCH AND INNOVATIONS IN COLLEGES 40 COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES (CAES) 41 COLLEGE OF BUSINESS AND MANAGEMENT SCIENCES (COBAMS) 76 COLLEGE OF COMPUTING AND INFORMATION SCIENCES (COCIS) 86 COLLEGE OF EDUCATION AND EXTERNAL STUDIES (CEES) 95 COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING, DESIGN, ART AND TECHNOLOGY (CEDAT) 114 COLLEGE OF HEALTH SCIENCES (CHS) 124 COLLEGE OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES 168 COLLEGE OF NATURAL SCIENCES (CONAS) 187 COLLEGE OF VETERINARY MEDICINE, ANIMAL RESOURCES AND 201 BIOSECURITY (COVAB) SCHOOL OF LAW 215 4 RESEARCH AT MAKERERE UNIVERSITY 2018 Message from the Message from the Vice Chancellor I am pleased to introduce this year’s Annual Research Report, which illustrates Makerere University’s shared commitment to advancing excellence in education, research, and scholarship. It takes a team to build a great university. As I research into solutions to societal problems. review the details of this report it is clear that the We act with full conscious that as a public accomplishments recounted here are the result of research university, fulfilling our mission extraordinary teamwork by the University’s most requires research and scholarship that address important asset — its people. The Directorate the significant challenges we face in our of Research and Graduate Training, the faculty, communities, across the nation and around the the staff and most importantly, our students: region. -

Year Book for 2006

Makerere University Institute of Public Health IPH-CDC HIV/AIDS FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM Fellows October 2004-2006 Year Book - C H D P C I HIV/AIDS Developing y Pr cit ogr apa am Management C In Uganda 1 CONTENTS Forward ................................................................................2 Acknowledgments...............................................................3 Fellowship Brief ...................................................................4 Short Courses .......................................................................5 Host Institution Profiles................................................. 6-16 Fellows October 2004 - 2006 ....................................... 17- 30 Alumni News ............................................................... 31-33 Contacts ............................................................................ 34 2 Forward With the 4th intake of IPH-CDC Fellows, the program has been able to further expand its geographical coverage, serve new target groups and engage in new activities. Some of our new ventures during the tenure of the October 2004 - 2006 Fellows were working with rural conflict affected communities in Bundibugyo, Apac and Katakwi; underserved urban poor in Mbuya Kampala; uniformed personnel in the Uganda Peoples Defense Forces; counseling and psychosocial support plus interventions related to orphans and vulnerable children at national and district level. The varied activities undertaken by the Fellows indicated heightened organizational interest in aspects related to -

Annual Report 2012 - 2013

MUSPH Annual Report Makerere University School of Public Health Annual Report 2012 - 2013 01 MUSPH Annual Report The Vision: “To be a centre of excellence providing leadership in Public Health” The Mission: “To promote the attainment of better health for the people of Uganda and beyond through Public Health Training, Research and Community service, with the guiding principles of Quality, Relevance, Responsiveness, Equity and Social Justice”. Values: ¡ Integrity; ¡ Openness; and, ¡ Team Spirit. 02 MUSPH Annual Report 2012 - 2013 MUSPH Annual Report Contents Teaching and Learning.................. 1 Research and Innovations ....... 8 Service to Community ................. 23 Publications ...................................... 29 Financial Report ........................... 32 MUSPH Annual Report 2012 - 2013 iii MUSPH Annual Report Dean’s Over view Dear Reader, am delighted to, once again, share with you this documentation of our achievements at the School of Public Health (MakSPH). The School of Public Health prides itself in being a leader in the field of public health research and training, in the East and Central African Iregion. The year 2012-2013 has been very productive and eventful at the School of Public Health. In academics and training, we have registered increased enrollment and improved performance for our undergraduate students. On the postgraduate front, we have seen the establishment of new programmes; the Master of Public Health Disaster Management received the much-anticipated nod of approval from the relevant bodies. While two existing programmes; Master of Public Health and Master of Health Services Research also had their curricula reviewed. Our CDC-funded HIV/AIDS Fellowship programme has continued to grow stronger, attracting more fellows and institutions interested in the fellows. -

MNCH Centre 2018 Annual Report

MAKERERE UNIVERSITY CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE FOR MATERNAL NEWBORN AND CHILD HEALTH Contact us:- Dr Peter Waiswa - Associate Professor and Centre Team Leader Email: [email protected], Tel: +256 772405357/0414530291 Contents Abbreviations ........................................................................ 2 From our Leaders ................................................................ 3 Achievements for 2018 ....................................................... 5 Advancing research and innovation in key priority MNCH areas ......................................................................... 8 Research ................................................................................. 8 Communications .................................................................. 9 Centre in the media ........................................................... 9 Social media engagement: ................................................... 9 Conferences, Seminars and presentations ......................... 10 Policy engagement..............................................................12 A regional approach to improving MNCH quality ..... 14 World Prematurity Day commemoration in Uganda 16 Publications ...........................................................................................20 Partners ..................................................................................................21 Annual Report 2018 1 Abbreviations EQUIST Equitable Impact Sensitive Tool MaKSPH Makerere University School of Public Health MDGs Millennium -

Preventing Ebola in Uganda: Case Study from the Makerere University School of Public Health and the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security

PREVENTING EBOLA IN UGANDA: CASE STUDY FROM THE MAKERERE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH AND THE JOHNS HOPKINS CENTER FOR HEALTH SECURITY By Lucia Mullen (i), Steven Ssendagire (ii), Christina Potter (i), Rhoda Wanyenze (ii), Alex Ario Riolexus (ii), Doreen Tuhebwe (ii), Susan Babirye (ii), Rebecca Nuwematsiko (ii), Jennifer Nuzzo (i) (see institutional affiliations) Introduction The Kivu Ebola epidemic began on August 1, 2018, when four cases were confirmed in North Kivu Province in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). 1 To date, the epidemic has led to over 3,400 confirmed and suspected cases in the DRC and over 2,200 deaths. Because there is frequent movement from North Kivu across the border into Uganda, including a regular influx of refugees, the Ugandan government and its partners put themselves on high alert and mobilized resources to prevent the importation of cases, detect imported disease quickly, contain the spread of imported disease, and treat sick people appropriately. In June 2019 the virus reached Uganda, but only four imported cases have been reported as of May 2020 and no in-country transmission has occurred. 2 Uganda has focused on preventing an outbreak and detecting cases. Prevention activities included assembling a multisectoral team and establishing robust coordinating mechanisms, running simulation exercises to assess the country’s readiness, and implementing a prophylactic vaccination effort among frontline workers and contacts of suspected cases. Detection activities included health communications and messaging and cross-border surveillance in collaboration with officials from the DRC. These accomplishments, despite foundational challenges facing Uganda’s health system, prompted Makerere University School of Public Health and the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security to conduct this study, based on an in-depth gray literature review and key informant interviews. -

(IFEH) WORLD ACADEMIC and 16Th MAKERERE UNIVERSITY

3rd INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION OF ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH (IFEH) WORLD ACADEMIC AND 16th MAKERERE UNIVERSITY ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH STUDENTS’ ASSOCIATION (MUEHSA) SCIENTIFIC CONFERENCE THEME - ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH: A CORNERSTONE TO ACHIEVING THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS 9th - 11th April 2019 Hotel Africana, Kampala, Uganda PROGRAMME MONDAY (8thAPRIL 2019) EARLY ONSITE REGISTRATION OF CONFERENCE PARTICIPANTS (14:00 – 18:00) DAY 1 (TUESDAY 9thAPRIL 2019) TIME SESSION 1 SESSION 2 SESSION 3 SESSION 4 08:00 - 08:30 Arrival and registration of participants 08:30 - 09:15 KEY NOTE ADDRESS 1 (NILE HALL) Topic: Environmental Health Training in the era of the Sustainable Development Goals Presenter: Prof. John Opuda-Asibo (Former Executive Director, National Council for Higher Education, Uganda) Moderator: Dr. John Ssempebwa (Makerere University, Uganda) 09:15 - 10:30 PANEL DISCUSSION 1 (NILE HALL) Topic: Engineering Environmental Health training and practice to tackle global health challenges Chair: Dr. Lisa Bricknell (Central Queensland University, Australia) Panellists 1. Overview of Environmental Health in Uganda with a focus on sanitation and hygiene – Ms. Julian Kyomuhangi (Ministry of Health, Uganda) 2. The Africa Academy of Environmental Health – Dr. David Musoke (Makerere University, Uganda) 3. Environmental Health training in the US – Dr. Jason W. Marion (Eastern Kentucky University, USA) 10:30 - 11:00 TEA BREAK / POSTER PRESENTATIONS 11:00 - 13:00 CONFERENCE OPENING (NILE HALL) Moderator: Dr. Juliet Babirye (Makerere University, Uganda) 11:00 - 11:30 Anthems / Entertainment Secretariat 11:30 - 11:40 Overview of conference – Conference Chair, Makerere University School of Public Health, Uganda Dr. David Musoke 11:40 - 11:50 Background to Makerere University Environmental Health Students’ Association (MUEHSA) – Conference Co- Mr. -

I Would Like to Be Part of the Team Distributing The

“I would like to be part of the team distributing the kits because I have all the qualities” Formative research to inform the development of a peer-led HIV self-testing intervention to improve HIV testing uptake and linkage to HIV care among young people and adult men in Kasensero shing community, Rakai, Uganda Joseph KB Matovu ( [email protected] ) Makerere University School of Public Health https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6480-2940 Aminah Nambuusi Makerere University School of Medicine Scovia Nakabirye Makerere University School of Public Health David Serwadda Makerere University School of Public Health Rhoda Wanyenze Makerere University School of Public Health Research Keywords: Peer-led, HIV, self-testing, shing community Posted Date: May 19th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-28819/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/19 Abstract Background Despite efforts to improve HIV testing and linkage to HIV care among young people and adult men, uptake rates remain below global targets. We conducted formative research to generate data necessary to inform the design of a peer-led HIV self-testing (HIVST) intervention intended to improve HIV testing uptake and linkage to HIV care among young people and adult men in Kasensero shing community in rural Uganda. Methods This was a cross-sectional, qualitative study conducted in three study communities in Kasensero shing community in Rakai district, Uganda, between May 6 – 10, 2019. Six single-sex focus group discussions (FGDs) comprising 7-8 participants were conducted with young men (15-24 years), young women (15-24 years) and adult men (25+ years). -

Makerere University College of Health Sciences School of Public Health

MAKERERE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF HEALTH SCIENCES SCHOOL OF PUBLIC HEALTH MakSPH - CDC FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM LONG-TERM FELLOWS 2013 - 2014 YEAR BOOK MAKERERE UNIVERSITY TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Foreword Word from the Principal Investigator 4 Fellowship Program Brief 5 FELLOWS: FEBRUARY 2013 – NOVEMBER 2014 6 Daniel Mwanja-Mumpe 6 Francis Lwanga 10 Joan Kabayambi 14 Michael Kasusse 18 Sharon Nakanwagi 21 Vincent Kiberu 25 Elizabeth Margret Asiimwe 28 Rosette Mugumya 32 Sharon Ahumuza 35 David Roger Walugembe 38 Michael Owor Odoi 42 Anne Nabukenya Mulindwa 45 Stephen Galla Alege 48 Matthew Lukwiya Award Winners 52 Program staff contacts 53 pg 2 MakSPH-CDC Fellowship Program Year Book 2014 FOREWORD Twelve years ago, the Fellowship Program was launched at In 2012 the Fellowship Program received additional funding Makerere University School of Public Health. Since that time, from the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention this program has created a great impact on health workforce (CDC), for another five-year phase, and this in itself is a vote development. As I write, we have so far trained 107 long-term of confidence from the funders, that we should be proud of. Fellows and 207 Medium-term Fellows, majority of whom This funding will continue to support existing Fellowships and are employed in high-level positions in government and non- graduate training at the School of Public Health. In this new government organizations in Uganda and elsewhere. In the phase we are exploring further adjustments that will ensure first five years, the program focused on supporting Fellows relevance and continued contribution to the strengthening of to acquire skills in managing HIV/AIDS programs. -

Maksph Newsletter 1St Edition 2021

MakSPH QUARTERLY PUBLICATION Issue 1 Vol. 1 JANUARY-MARCH 2021 Jhpiego Ranks MakSPH High in Latest Capacity Assessment Message From Dean Hello and welcome to our quarterly newsletter covering the months of January to March 2021. I hope all of you are safe and well amidst the uncertain times of COVID-19. In this issue, we bring you a snapshot of what we have been able to do in the past 3 months. You will hear more of our progress in terms of research outputs, our teaching and innovations as the leader in Public Members and Heads of Units at MakSPH in a group photo with a team from Jhpiego nd Health education and research in Sub- after sharing results of the 2 OCA in February 2021. Photo by Davidson Ndyabahika Saharan Africa. akerere University School of Public Health How Faith Atai Obtained Also, we are making good progress on scored highly during the 2nd Organizational M First Class Degree at infrastructure development project and I Capacity Assessment (OCA), conducted by 6 School of Public Health am happy to share that the construction of Jhpiego, an international, non-profit health our new home is taking shape. We expect organization and an affiliate of The Johns CHS-MakSPH, Family TV to receive a complete structure of our Hopkins University. Uganda Partnership Give 10 modern auditorium in May this year. This Birth to a Health Show milestone brings us even closer to providing As per the Jhpiego Organizational Capacity (JOC) the population with evidence in complex toolkit, organisations implementing projects Uganda’s Home-grown emerging issues in public health in Uganda, globally undergo thorough capacity assessment trials for coronavirus drug 15 Africa and beyond.