The Republic of Trinidad and Tobago in the Court Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Directory

MEDIA DIRECTORY The media is an essential outlet for NGOs and civil society organizations to inform the general public, funders, clients and other key stakeholders about their organisation’s programs, events, projects and more. Sponsored by the JB Fernandes Memorial Trust II, the T&T NGO Professionals Media Directory includes contact information on the major print newspapers, television stations, community newspapers, and digital publications in Trinidad and Tobago. Stay updated on NGO and civil society organisation news in Trinidad & Tobago online at: Website: www.ttngonews.com Facebook: www.facebook.com/ttngonews Twitter: www.twitter.com/ttngonews TABLE OF CONTENTS TRINIDAD & TOBAGO PRINT NEWSPAPERS ................................................................................................................ 2 TELEVISION STATIONS ............................................................................................................ 4 COMMUNITY PRINT NEWSPAPERS (Trinidad Only) .................................................................. 6 MAGAZINES ............................................................................................................................. 6 DIGITAL PUBLICATIONS ........................................................................................................... 7 NEWS RADIO STATIONS .......................................................................................................... 8 TOBAGO PRINT NEWSPAPERS ............................................................................................................... -

Harvard Business School Tourism in Trinidad and Tobago

Harvard Business School Microeconomics of Competitiveness Tourism in Trinidad and Tobago Basilia Yao, Jan Krutzinna, Jennifer Chen, Kwabena Osei-Boateng, Tanveer Abbas May 5, 2006 Disclosure Note: Kwabena and Jan traveled to Trinidad for leisure/tourism during the project period. Introduction This paper analyzes the economy of Trinidad and Tobago and provides a strategic plan for developing the tourism cluster. Using the diamond model for competitiveness developed by Professor Michael Porter, we examine the strengths and weaknesses of the national economy, identify opportunities for improving the tourism cluster, and provide a set of policy recommendations to capture these opportunities. Macro-economic overview of Trinidad and Tobago Trinidad and Tobago (“T&T”) is a small energy-rich Caribbean economy. It has a population of 1,065,842 and a land area of 5,128 sq km (smaller than Delaware). The country came under British control in the 19th century and gained its independence in 1962. The ethnic mix of the country is approximately 40% Indian, 37.5% African, and about 21% mixed. The judicial system is based on English common law and the country has a bicameral Parliament which consists of the Senate and Tourism in Trinidad and Tobago Page 1 of 31 the House of Representatives.1 The Energy Curse The country is one of the most prosperous in the Caribbean because of its energy reserves. It has the world’s 43rd largest proven oil reserves and the world’s 33rd largest proven natural gas reserves.2 The oil and gas sector currently accounts for about 40 percent of GDP and 80 percent of exports. -

Non-Revenue (Airline Staff) Travel by Kerwin Mckenzie

McKenzie Ultimate Guides: A Guide to Non-Revenue (Airline Staff) Travel By Kerwin McKenzie McKenzie Ultimate Guides: Non-Revenue (Airline Staff) Travel Copyright Normal copyright laws are in effect for use of this document. You are allowed to make an unlimited number of verbatim copies of this document for individual personal use. This includes making electronic copies and creating paper copies. As this exception only applies to individual personal use, this means that you are not allowed to sell or distribute, for free or at a charge paper or electronic copies of this document. You are also not allowed to forward or distribute copies of this document to anyone electronically or in paper form. Mass production of paper or electronic copies and distribution of these copies is not allowed. If you wish to purchase this document please go to: http://www.passrider.com/passrider-guides. First published May 6, 2005. Revised May 10, 2005. Revised October 25, 2009. Revised February 3, 2010. Revised October 28, 2011. Revised November 26 2011. Revised October 18 2013. © 2013 McKenzie Ultimate Guides. All Rights Reserved. www.passrider.com © 2013 – MUG:NRSA Page 1 McKenzie Ultimate Guides: Non-Revenue (Airline Staff) Travel Table of Contents Copyright ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 About the Author ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

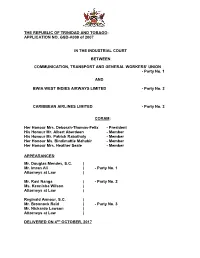

The Republic of Trinidad and Tobago: Application No

THE REPUBLIC OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO: APPLICATION NO. GSD-A009 of 2007 IN THE INDUSTRIAL COURT BETWEEN COMMUNICATION, TRANSPORT AND GENERAL WORKERS’ UNION - Party No. 1 AND BWIA WEST INDIES AIRWAYS LIMITED - Party No. 2 CARIBBEAN AIRLINES LIMITED - Party No. 3 CORAM: Her Honour Mrs. Deborah-Thomas-Felix - President His Honour Mr. Albert Aberdeen - Member His Honour Mr. Patrick Rabathaly - Member Her Honour Ms. Bindimattie Mahabir - Member Her Honour Mrs. Heather Seale - Member APPEARANCES: Mr. Douglas Mendes, S.C. ) Mr. Imran Ali ) - Party No. 1 Attorneys at Law ) Mr. Ravi Nanga ) - Party No. 2 Ms. Kennisha Wilson ) Attorneys at Law ) Reginald Armour, S.C. ) Mr. Bronnock Reid ) - Party No. 3 Mr. Nickardo Lawson ) Attorneys at Law ) DELIVERED ON 4TH OCTOBER, 2017 JUDGMENT This application has some history before the Industrial Court. There have been a number of interlocutory hearings and a ruling on a preliminary point by the Court of Appeal before the commencement of the actual hearing. Final submissions were filed on 31st May, 2017 and we can now give a determination on the issues at hand. 1. The Communication, Transport and General Workers’ Union (the “Union”) is a registered Trade Union and the Recognised Majority Union for some of the bargaining units of BWIA West Indies Airways Limited (“BWIA”). BWIA is a Company registered under the Companies Act, Chapter 81:01, and was the national airline and “flag carrier” of Trinidad and Tobago until 31st December, 2006. Its principal shareholder was the Government of Trinidad and Tobago. Caribbean Airlines Limited (“CAL”) is a Company also registered under the Companies Act, Chapter 81:01. -

Bwia West Indies Airways Limited

BWIA WEST INDIES AIRWAYS LIMITED REGISTERED OFFICE: Sunjet House 30 Edward Street Port of Spain Trinidad & Tobago TELEPHONE: (868) 627-2942 (868) 625-1845 WEBSITE: www.bwee.com E-MAIL: [email protected] ADMINISTRATION OFFICES: Administration Building Golden Grove Road Piarco Trinidad & Tobago TELEPHONE: (868) 669-3000 FAX: (868) 669-1680 BWIA 2004-11 BWIA WEST INDIES AIRWAYS LIMITED REGISTRAR: BWIA West Indies Airways Limited Golden Grove Road Piarco Trinidad & Tobago DIRECTORS: Lawrence A. Duprey, CMT – Chairman Charles Anthony Jacelon, SC – Dep. Chairman Krishna Narinesingh, CMT Captain John O’Brien Rodney Sastri Prasad Michael Small Neil Parsanlal GENERAL MANAGER: Nelson Tom Yew SECRETARY: Nicole Richards BANKERS: RBTT Bank Limited Citibank N.A Royal Court 111 Wall Street, New York 19 – 21 Park Street New York, 10043 Port of Spain United States of America. Trinidad and Tobago BWIA 2004-11 BWIA WEST INDIES AIRWAYS LIMITED ATTORNEYS-AT-LAW: Pollonais, Blanc, de la Bastide & Jacelon 17 - 19 Pembroke Street Port of Spain Trinidad &Tobago SUBSIDIARIES: West Indies Aircraft Limited (Cayman Islands) - 100.00% West Indies Aircraft Limited 2 (Cayman Islands) - 100.00% Allied Caterers Limited (Trinidad & Tobago) - 55.00% Tobago Express Limited (Trinidad & Tobago) – 49.00% ASSOCIATED COMPANY: LIAT (1974) Limited (Antigua) – 23.60% AUDITORS: PricewaterhouseCoopers 11-13 Victoria Avenue Port of Spain Trinidad & Tobago BWIA 2004-11 BWIA WEST INDIES AIRWAYS LIMITED HISTORY AND BUSINESS: The Company traces its origins to British West Indian Airways, a privately owned airline which served the routes of Trinidad, Barbados and Tobago. The original airline was founded in 1940. By the 1950s, these routes had expanded to include services to Miami, Florida, USA, Venezuela, and Jamaica. -

Caribbean Regional Sustainable Tourism Development Programme

Caribbean Regional Sustainable Tourism Development Programme Project No. 8 ACP RCA 035 FINAL REPORT: CARIBBEAN AIR TRANSPORT STUDY FOR CARIBBEAN TOURISM ORGANISATION - LOT 1 RESEARCH CAPACITY 26July 2006 Caribbean Regional Sustainable Tourism Development Programme Project No. 8 ACP RCA 035 FINAL REPORT: CARIBBEAN AIR TRANSPORT STUDY FOR CARIBBEAN TOURISM ORGANISATION - LOT 1 RESEARCH CAPACITY 26July 2006 © PA Knowledge Limited 2006 PA Consulting Group 123 Buckingham Palace Road Prepared by: Ian Bertrand London SW1W 9SR Air Transportation Tel: +44 20 7730 9000 Consultant Fax: +44 20 7333 5050 www.paconsulting.com Version: 4.0 Caribbean Regional Sustainable Tourism Development Programme 28/7/06 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary 1-1 1.1 APPROACH TO THE STUDY 1-2 1.2 SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS 1-3 1.3 INTERNATIONAL ‘OPEN SKIES’ AGREEMENTS 1-4 1.4 INTRA-REGIONAL ‘OPEN SKIES’ 1-5 1.5 STRENGTHENING THE DOMICILE AIRLINES 1-5 2. Introduction 2-1 2.1 OBJECTIVE OF THE STUDY 2-1 2.2 APPROACH TO THE STUDY 2-2 3. Situational Analysis 3-1 3.1 THE CONCEPT OF RISK MITIGATION 3-1 3.2 CURRENT STATUS OF RISK MITIGATION 3-1 3.3 CARIFORUM AIRLINES 3-3 3.4 NON-CARIFORUM CTO MEMBERS 3-3 4. Optimising the Liberalisation Mechanism 4-1 4.1 THE LATIN AMERICAN/CARIBBEAN EXPERIENCE 4-2 4.2 INTERNATIONAL ‘OPEN SKIES’ 4-2 4.3 THE CARIFORUM STATUS 4-3 4.4 INTRA-REGIONAL ‘OPEN SKIES’ 4-4 5. Strengthening the Domicile Airlines 5-1 5.1 RECOMMENDATIONS 5-1 Appendices APPENDIX A: Preliminary Report - The Current Aviation Environment in the Caribbean A-1 APPENDIX B: Interim -

Caribbean Aviation Meetup June 14 – 16, 2006, Dominica

Caribbean Air Transport: The Struggle for a local long term sustainable airline business model continuous. Since the 1950’s, a long term sustainable business model has been illusive like the search for the Holy Grail. Too many airlines have tried and failed and even today, the few that survive are just that, surviving at best, but why ? In Search of a Long Term Sustainable Airline Business Model in the Caribbean Caribbean Aviation Meetup June 14 – 16, 2006, Dominica Presented by Tomas Chlumecky www.AviationDoctor.wordpress.com Some of the 60+ Caribbean Airlines out of business since 1981 Aero Wings Cardinal Airlines Carib Express Carib Aviation BWIA Air BVI Caribbean Star Tobago Express British Caribbean Airways RedJet Helen Air St. Lucia Airways Trans Island Air 2000 Curacao Excel Seagreen Air Transport Air Monserrat Dominair Avia Air Air Caribbean Dominica Fly Aruba Air Calypso Nomad Air Aruba Express Air Aruba Dutch Caribbean Express Antilles Air Boats Air d’Ayiti Dorado Air Aero Virgin Islands Air Jamaica Eagle Air Carib Air EC Express V.I. Seaplane Shuttle Laker Airways Air ALM Guyana Airways Maya Airways Nature Island Express Air Jamaica Express Prinair Global Airline Start-ups and Bankruptcies In 2015, there were 58 new start-up airlines and 55 airline failures. e.g. Canjet, Transaero, Estonian Air, Freedom Air In 2014 there were 83 start-ups and 44 failures. Average number of new start ups was 26 in the 1970’s, 40 in the 1980’s, and 81 in the 1990’s. 2002 to 2004 saw 120+ new start-ups per year. Failures peaked at 123 in 2008. -

Tobago, the University of the West Soaring Price of Oil in 2008 Is a Double- Indies at St Augustine

2008/9 i ii From the editor “Things look different depending on “extraordinarily high energy costs and where you sit or stand.” That was a recessionary trends in the world’s largest favourite saying of the late Dr Herb economy, the Unites States of America, Addo, who was a lecturer which could affect industrial output in at the Institute of countries around the world.” International Relations, For Trinidad and Tobago, the University of the West soaring price of oil in 2008 is a double- Indies at St Augustine. edged sword, he said, driving up prices In Trinidad and for goods and services, while increasing Tobago, the adage seems national revenue. In June, inflation apt. Some see Trinidad crossed from single to double digits for and Tobago simply as the first time in 2008, as the price of a booming, prosperous food and other crucial products kept country, the tiger of the increasing. Caribbean. For others, Internally, the issue of crime is caution is the name of still a primary concern, especially for the game; they question the business community. Ian Collier, the sustainability of president of the Trinidad and Tobago the current economic Chamber of Commerce, warned situation, given the in June that business leaders were volatile prices of oil migrating because of crime, despite the and gas and the the government’s determination to promote Ryder Scott audit the country as an international financial which puts proven gas centre. reserves at only 13 years It is against this backdrop that the at the present rate of 2008/9 issue of the Trinidad and Tobago extraction. -

Crime, Violence and Development: Trends, Costs, and Policy Options In

Report No. 37820 Crime, Violence, and Development: Trends, Costs, and Policy Options in the Caribbean March 2007 A Joint Report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and the Latin America and the Caribbean Region of the World Bank ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ADR Alternative Dispute Resolution CEM Country Economic Memorandum CFATF Caribbean Financial Action Task Force CGNAA COSAT Guard for the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba CONANI Consejo Nacional de la Niñez CPI Corruption Perceptions Index CPTED Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design CTS Crime Trends Surveys – United Nations DALYs Disability-Adjusted Life Years DHS Department of Homeland Security EBA Educación Básica para Adultos y Jóvenes ECLAC Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean ENHOGAR Encuesta Nacional de Hogares de Propósitos Múltiples EU/LAC European Union/Latin American and the Caribbean FARC Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia GDP Gross Domestic Product ICS Investment Climate Survey ICVS International Crime Victims Survey LAC Latin America and Caribbean OECS Organization of Eastern Caribbean States PATH Program for Appropriate Technology in Health RNN Royal Navy of the Netherlands RSS Regional Security System RTFCS Regional Task Force on Crime and Security UNODC United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime WDR World Development Report WHO World Health Organization Vice President: Pamela Cox Country Director: Caroline Anstey PREM Director: Ernesto May Sector Manager: Jaime Saavedra Chanduvi Lead Economist: Antonella Bassani Task Managers: -

Caribbean Airlines Limited

5th REPORT OF THE on An Inquiry into the Administration and Operations of Caribbean Airlines Limited. September 2017 1 5th Report, JSC State Enterprises - CAL An electronic copy of this report can be found on the Parliament website: www.ttparliament.org The Joint Select Committee on State Enterprises Contact the Committees Unit Telephone: 624-7275 Extensions 2828/2309/2283, Fax: 625-4672 Email: [email protected] 2 5th Report, JSC State Enterprises - CAL Joint Select Committee on State Enterprises An Inquiry into the Administration and Operations of Caribbean Airlines Limited Fifth Report 2016/2017 Session, Eleventh Parliament Report, together with Minutes Ordered to be printed Date Laid Date Laid H.o.R: Senate: Published on ________ 201__ 3 5th Report, JSC State Enterprises - CAL 4 5th Report, JSC State Enterprises - CAL The Joint Select Committee on State Enterprises Establishment 1. The Joint Select Committee on State Enterprises was appointed pursuant to the directive encapsulated at section 66A of the Constitution of the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago. The House of Representatives and the Senate on Friday November 13, 2015 and Tuesday November 17, 2015, respectively agreed to a motion, which among other things, established this Committee to inquire into and report to Parliament on State Enterprises falling under its purview with regard to: their administration; the manner of exercise of their powers; their methods of functioning; and any criteria adopted by them in the exercise of their powers and functions. Current Membership 2. The following Members were appointed to serve on the Committee: Mr. David Small Dr. Lester Henry Mrs. -

(Enterprises) Committee

Second Report of the Public Accounts (Enterprises) Committee, Third Session, 10th Parliament on Caribbean Airlines Limited [Examination of the Audited Financial Statements for the year ended December 31, 2008.] Ordered to be printed in the House of Representatives and Senate Table of Contents Page Members of the PA(E)C ……………………………………………. 3 Executive Summary ……………………………………………. 5 Chapter 1 – The Committee .…………………………………………… 6 Chapter 2 - Report on Entity Examined …………………………………… 8 Chapter 3 - Specific Recommendations ………………………………….. 12 Chapter 4 - General Recommendations …………………………………… 13 Appendix A – Minutes of Meeting Appendix B – Verbatim Notes of Meetings Appendix C –Meeting Attendence 2 MEMBERS OF THE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS (ENTERPRISES) COMMITTEE – TENTH PARLIAMENT, REPUBLIC OF TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO Mr. Fitzgerald Hinds - Chairman Mr. Rudranath Indarsingh - Member Mr. Errol McLeod - Member Mr. Herbert Volney - Member Mr. Colm Imbert - Member Mrs. Paula Gopee-Scoon - Member Ms. Marlene Coudray - Member Mr. Fazal Karim - Member Mr. Embau Moheni - Member Dr. Rolph Balgobin - Member 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Second Report of the Public Accounts (Enterprises) Committee (P.A.(E).C) of the Tenth Parliament examines the following entity: The Caribbean Airlines Limited on its audited financial statements for the year ended December 31, 2008; Chapter 1 presents details of the Public Accounts (Enterprises) Committee established in the Tenth Republican Parliament, the Election of a Chairman and determination of the Committee’s Quorum. It also includes the particulars of Meetings held with the entity under report and the Staff of the Committee. The work undertaken by your Committee, including the main issues, findings and recommendations of your Committee in respect of Caribbean Airlines Limited are contained within Chapter 2 of this Report. -

Caribbean Airlines: Two Years and Counting by Ken Donohue KEN DONOHUE

Caribbean Airlines: Two Years and Counting by Ken Donohue KEN DONOHUE Three years ago, the two-island “In the end, the government was in favor of giving the industry another opportunity to prove it could Caribbean nation of Trinidad and succeed in Trinidad and Tobago,” says Philip Saunders, CEO of Caribbean Airlines. On December 31, 2006, the doors were closed at BWIA, and a day later a new Tobago faced the prospect of having no era began with the launch of Caribbean Airlines (IATA: BW/ICAO: BWA). air service to call its own. BWIA West Saunders spent 13 years at British Airways before joining Brussels Airlines, the incarnation of SN Brussels Indies Airways (Airways, November Airlines (Airways, January 2008 & September 2003), as commercial director. Most recently, he was VP commercial 2002), which had been the country’s at the Star Alliance. Peter Davies, who was once the head of SN Brussels when Saunders was there, was the national airline for more than 40 years, transitional CEO at BWIA, and he alerted Saunders to the opening at Caribbean. “I have always sought opportunity was floundering and on the verge of and challenge,” remarks Saunders. “My time at Caribbean has been a fascinating journey.” collapse. ‘BWee’ was losing a lot of The government was very clear in its mandate to the ‘new BWee’ that it wanted to see a profitable operation. money, especially on long-haul routes. To this end, route consolidation was one of the first things on the agenda. Caribbean has a rigid standard for its network: if it doesn’t make economic sense, the route The government did an analysis of the won’t be flown.