Suffolk Coast Otter Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Species Knowledge Review: Shrill Carder Bee Bombus Sylvarum in England and Wales

Species Knowledge Review: Shrill carder bee Bombus sylvarum in England and Wales Editors: Sam Page, Richard Comont, Sinead Lynch, and Vicky Wilkins. Bombus sylvarum, Nashenden Down nature reserve, Rochester (Kent Wildlife Trust) (Photo credit: Dave Watson) Executive summary This report aims to pull together current knowledge of the Shrill carder bee Bombus sylvarum in the UK. It is a working document, with a view to this information being reviewed and added when needed (current version updated Oct 2019). Special thanks to the group of experts who have reviewed and commented on earlier versions of this report. Much of the current knowledge on Bombus sylvarum builds on extensive work carried out by the Bumblebee Working Group and Hymettus in the 1990s and early 2000s. Since then, there have been a few key studies such as genetic research by Ellis et al (2006), Stuart Connop’s PhD thesis (2007), and a series of CCW surveys and reports carried out across the Welsh populations between 2000 and 2013. Distribution and abundance Records indicate that the Shrill carder bee Bombus sylvarum was historically widespread across southern England and Welsh lowland and coastal regions, with more localised records in central and northern England. The second half of the 20th Century saw a major range retraction for the species, with a mixed picture post-2000. Metapopulations of B. sylvarum are now limited to five key areas across the UK: In England these are the Thames Estuary and Somerset; in South Wales these are the Gwent Levels, Kenfig–Port Talbot, and south Pembrokeshire. The Thames Estuary and Gwent Levels populations appear to be the largest and most abundant, whereas the Somerset population exists at a very low population density, the Kenfig population is small and restricted. -

England Coast Path Report 2 Sizewell to Dunwich

www.gov.uk/englandcoastpath England Coast Path Stretch: Aldeburgh to Hopton-on-Sea Report AHS 2: Sizewell to Dunwich Part 2.1: Introduction Start Point: Sizewell beach car park (grid reference: TM 4757 6300) End Point: Dingle Marshes south, Dunwich (grid reference: TM 4735 7074) Relevant Maps: AHS 2a to AHS 2e 2.1.1 This is one of a series of linked but legally separate reports published by Natural England under section 51 of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949, which make proposals to the Secretary of State for improved public access along and to this stretch of coast between Aldeburgh to Hopton-on-Sea. 2.1.2 This report covers length AHS 2 of the stretch, which is the coast between Sizewell and Dunwich. It makes free-standing statutory proposals for this part of the stretch, and seeks approval for them by the Secretary of State in their own right under section 52 of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. 2.1.3 The report explains how we propose to implement the England Coast Path (“the trail”) on this part of the stretch, and details the likely consequences in terms of the wider ‘Coastal Margin’ that will be created if our proposals are approved by the Secretary of State. Our report also sets out: any proposals we think are necessary for restricting or excluding coastal access rights to address particular issues, in line with the powers in the legislation; and any proposed powers for the trail to be capable of being relocated on particular sections (“roll- back”), if this proves necessary in the future because of coastal change. -

Guide Price £100,000 Marsh Land, Eastbridge, IP16

Marsh Land, Eastbridge, IP16 4SL Guide Price £100,000 Property Summary Opportunity to acquire your own private 17 acre nature reserve which is brimming with wildlife and birdsong. It is in a great location on the edge of Eastbridge, which abuts Minsmere and is a short drive from the glorious Heritage Coast. Property Features The land is in the region of 17 acres It is accessed via a five bar gate off Chapel Road on the edge of Eastbridge Set on a quiet lane within walking distance of the Eels foot Inn public house This pretty marsh/woodland offers a peaceful setting Complete with natural pond Perfect Sanctuary for wildlife/nature lovers Property Description Directions This private haven is a pure delight to those seeking From the Eels Foot Inn, on the right take the lane on the their own secluded marsh/woodland to enjoy and left into Chapel Road and wind through the house for experience nature first hand. At present, there are 300/400 yards. At the knoll continue on the right hand grazing rights to enable the grass land to be utilised at side. Once there are fields on either side of road, the certain times of the year (Please enquire for further land can be accessed via a 5 bar gate on the right hand details). All in all, a perfect spot for peace, tranquillity & side with notice 'Private Road' and the Druce 'For Sale' beauty, all within a few minutes’ walk of a popular sign. meeting place and watering hole. Viewings About The Area By accompanied appointment with a member of staff. -

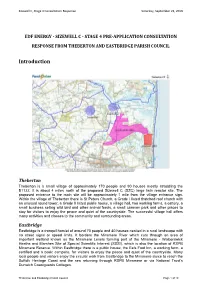

Introduction

Sizewell C, Stage 4 Consultation Response Saturday, September 21, 2019 EDF ENERGY - SIZEWELL C - STAGE 4 PRE-APPLICATION CONSULTATION RESPONSE FROM THEBERTON AND EASTBRIDGE PARISH COUNCIL Introduction Theberton Theberton is a small village of approximately 170 people and 90 houses mostly straddling the B1122. It is about 4 miles north of the proposed Sizewell C (SZC) large twin reactor site. The proposed entrance to the main site will be approximately 1 mile from the village entrance sign. Within the village of Theberton there is St Peters Church, a Grade I listed thatched roof church with an unusual round tower, a Grade II listed public house, a village hall, two working farms, a cattery, a small business selling wild bird and other animal feeds, a small caravan park and other places to stay for visitors to enjoy the peace and quiet of the countryside. The successful village hall offers many activities and classes to the community and surrounding areas. Eastbridge Eastbridge is a tranquil hamlet of around 70 people and 40 houses nestled in a rural landscape with no street signs or speed limits. It borders the Minsmere River which cuts through an area of important wetland known as the Minsmere Levels forming part of the Minsmere - Walberswick Heaths and Marshes Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), which is also the location of RSPB Minsmere Reserve. Within Eastbridge there is a public house, the Eels Foot Inn, a working farm, a certified and a basic campsite, for visitors to enjoy the peace and quiet of the countryside. Many local people and visitors enjoy the circular walk from Eastbridge to the Minsmere sluice to reach the Suffolk Heritage Coast and the sea returning through RSPB Minsmere or via National Trust’s Dunwich Coastguards Cottages. -

Introduction 1. Relevant Representation

SCOTTISH POWER DEVELOPMENT CONSENT ORDER WRITTEN REPRESENTATION OF THEBERTON AND EASTBRIDGE PARISH COUNCIL (T&EPC) Introduction Theberton Theberton is a small village of approximately 170 people and 90 houses mostly straddling the B1122. It is about 4 miles north of the proposed Sizewell C (SZC) twin reactor site. The proposed entrance to the main site will be approximately 1 mile from the village. Within the village of Theberton there is St Peters Church, a Grade I listed thatched roof church with an unusual round tower, a Grade II listed public house, a village hall, two working farms, a cattery, a small business selling wild bird and other animal feeds, a small caravan park and other places to stay for visitors to enjoy the peace and quiet of the countryside. The successful village hall offers many activities and classes to the community, surrounding areas and hosts Duke of Edinburgh Award Scheme events. Eastbridge Eastbridge is a tranquil hamlet of around 70 people and 40 houses nestled in a rural landscape with no street signs or speed limits. It borders an area of important wetland known as the Minsmere Levels forming part of the Minsmere - Walberswick Heaths and Marshes Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), which is the location for RSPB Minsmere. Within Eastbridge there is a public house, the Eels Foot Inn, a working farm, a certified and a basic campsite, for visitors to enjoy the dark skies, the peace and quiet of the countryside. Many local people and visitors enjoy the circular walk from Eastbridge to the Minsmere sluice to reach the Suffolk Heritage Coast and the sea returning through RSPB Minsmere or via the National Trust’s Dunwich Coastguard Cottages. -

Dunwich & Minsmere

Suffolk Coast & Heaths Cycle Explorer Guide The Suffolk Coast & Heaths AONB The Suffolk Coast & Heaths Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) is one of Britain’s finest landscapes. It extends from the Stour estuary in the south to the eastern fringe of Ipswich and then north to Kessingland. The AONB Dunwich covers 403 square kilometres, including wildlife-rich wetlands, ancient heaths, windswept shingle beaches and historic towns and villages. Minsmere How to get to Dunwich Beach & car park or Darsham Station Cycle Explorer Guide Ordnance Survey Explorer Map No. 231 (Southwold and Bungay). In partnership with No. 212 (Woodbridge and Saxmundham) for part of route. Dunwich Beach car park: access via the B1122, the B1125 and unclassified roads from the A12. The car park gets very busy on summer Sundays and bank holidays. Darsham Station: the car park is very small, so only rail access is possible. Dunwich Beach car park: IP17 3EN Darsham Station is on the East Suffolk Line (hourly service Ipswich to Lowestoft). Train information: www.nationalrail.co.uk or call 08457 484950 Public transport information: www.suffolkonboard.com or call 0345 606 6171 www.traveline.info or call 0871 200 2233 Visitor information from www.thesuffolkcoast.co.uk Suffolk Coast & Heaths AONB 01394 445225 © Crown copyright and www.suffolkcoastandheaths.org database rights 2015 Ordnance Survey 100023395. This route visits the ancient parish of Dunwich The Dunwich & Minsmere Cycle Explorer Guide has been produced with the as well as the RSPB’s famous nature reserve at generous support of Adnams. They also Minsmere and the National Trust’s beautiful sponsor a number of cycling events across the region. -

Dunwich and Minsmere Cycling Explorers

Suffolk Coast & Heaths Cycle Explorer Guide The Suffolk Coast & Heaths AONB The Suffolk Coast & Heaths Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) is one of Britain’s finest landscapes. It extends from the Stour estuary in the south to the eastern fringe of Ipswich and then north to Kessingland. The AONB Dunwich covers 403 square kilometres, including wildlife-rich wetlands, ancient heaths, windswept shingle beaches and historic towns and villages. Minsmere How to get to Dunwich Beach & car park or Darsham Station Cycle Explorer Guide Ordnance Survey Explorer Map No. 231 (Southwold and Bungay). In partnership with (No. 212 (Woodbridge and Saxmundham for part of route). Dunwich Beach car park: access via the B1122, the B1125 and unclassified roads from the A12. The car park gets very busy on summer Sundays and bank holidays. Darsham Station: the car park is very small, so only rail access is possible. Dunwich Beach car park: IP17 3EN Darsham Station is on the East Suffolk Line (hourly service Ipswich to Lowestoft). Train information: www.nationalrail.co.uk or call 08457 484950 Public transport information: www.suffolkonboard.com or call 0845 606 6171 www.traveline.info or call 0871 200 2233 Aldeburgh Tourist Information: www.suffolkcoastal.gov.uk/ yourfreetime/tics/ or call 01728 453637 Suffolk Coast & Heaths AONB 01394 445225 © Crown copyright and www.suffolkcoastandheaths.org database rights 2015 Ordnance Survey 100023395. This route visits the ancient parish of Dunwich The Dunwich & Minsmere Cycle Explorer Guide has been produced with the as well as the RSPB’s famous nature reserve at generous support of Adnams. They also Minsmere and the National Trust’s beautiful sponsor a number of cycling events across the region. -

8A Minsmere Rise, Middleton, Saxmundham, Suffolk IP17 3PA Price £345,000

8A Minsmere Rise, Middleton, Saxmundham, Suffolk IP17 3PA Price £345,000 SOUTHWOLD SAXMUNDHAM T: 01502722065 T: 01728 605511 www.jennie-jones.com E: [email protected] E: [email protected] A beautifully presented modern single storey house which is well planned and offers a great deal of style and character. The property, which benefits from a pretty rear garden overlooking open pasture at the back, also features a driveway which affords good off street parking in front of the integral garage. The garage could be converted into additional living space if required, subject to the usual consents. The property is centrally heated by oil-fired radiators and is dou- ble glazed. It benefits from a smart kitchen/dining room and a sitting room which opens out to the garden. There are three double bedrooms served by a family shower room and ensuite bathroom. The property also benefits from a large roof space, lit by gable windows, which may offer scope for conversion subject to usual consents. Minsmere Rise is ideally located for access to the attractions of the Suffolk Heritage Coast and particu- larly RSPB Minsmere and Dunwich heath and beach. The property lies within a short walk of the village pub and primary school. Middleton village has its own pub, farm shop, garage and primary school. There are wonderful walks in this part of Suffolk at Dunwich Heath, Tunstall Forest, Iken Cliff and Blaxhall Common. There are ancient castles to explore at Orford and Framlingham and wonderful nature reserves at Minsmere, Havergate Island and North Warren. The nearby market town of Saxmundham has both Waitrose and Tesco supermarkets. -

Minsmere Pond

Welcome to our meetings For further information please visit us on 4 September Get close to the beasties in the Minsmere pond. www.rspb.org.uk/groups/minsmerewex or contact: 2 October Explore where in the woods mini beasts live. Louise Gregory Minsmere Wildlife Explorers, Group Leader MINSMERE 6 November c/o RSPB Minsmere nature reserve Westleton RSPB Wildlife Explorers Find out which habits nocturnal animals have. Saxmundham Autumn - Winter 2010/11 programme Suffolk 4 December IP17 3BY Celebrate with us, it’s Christmas party time! Tel: 01728 648 281 or [email protected] 1 January Join in the 2011 Minsmere wildlife race with staff If you would like to talk to someone about the way your and volunteers all over the reserve. group is run and how you are treated, please call the RSPB on 0800 9178566. Call betwen 9am and 5pm Monday to Friday to 5 February speak to someone. There is an answerphone at all other times. Build a home for wildlife. Child safety and welfare The RSPB takes all practicable steps to safeguard We hope to welcome you, your family, and many of your the safety and welfare of children and young people friends at our wonderful RSPB Minsmere nature reserve while they are in contact with the Society, observing the on the Suffolk coast near Westleton very soon. recomendations of the Home Office code of practise covering Scotland and Northern Ireland, and conforming with all the relevent legislation. RSPB Wildlife Explorers is for junior members of the RSPB. The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) is a registered charity: England and Wales no. -

Minsmere Nature Reserve – November 2012 to October 2013 Report to the Council of Europe

Minsmere Nature Reserve – November 2012 to October 2013 Report to the Council of Europe Country: United Kingdom Name of reserve: Minsmere Nature Reserve Central authority: The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds The Lodge, Sandy, Bedfordshire, SG19 2DL tel: 00 44 1767 680551 www.rspb.org.uk Minsmere Manager: Adam Rowlands Minsmere Nature Reserve Westleton, Saxmundham, Suffolk, IP17 3BY tel: 00 44 1728 648780 fax: 00 44 1728 648770 email: [email protected] www.rspb.org.uk/reserves/guide/m/minsmere/index.aspx Reserves Manager: Jon Haw RSPB East Anglia Regional Office Stalham House, 65 Thorpe Road, Norwich, NR1 1UD tel: 00 44 1603 660066 fax: 00 44 1603 660088 email: [email protected] I. GENERAL INFORMATION 1 Natural heritage 1.1 Environment The Environment Agency through their contractor continues to monitor the internal flood defence bank and the sluice structure against tolerances agreed in the designs. Divers replaced the seals in the sluice in February 2013 after leakage rates became unacceptable. This work appears to have resolved the issue. The Environment Agency have commenced a project in October 2012 to refurbish the main tidal sluice and raise embankments along the New Cut River which will reduce flooding into the southern reedbed areas and fen meadows. The Project experienced several delays including substantial rainfall over the spring and summer leading to the flooding of the Sluice Trail which was the main works access. Completed works from Phase I included: The establishment of the main compound near the Minsmere work centre and a satellite compound near the Tidal Sluice. -

The Sizewell C Project

Post Open Floor Hearing submission for the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds and Suffolk Wildlife Trust Submitted for Deadline 2 2 June 2021 Planning Act 2008 (as amended) In the matter of: Application by NNB Generation Company (SZC) Limited for an Order Granting Development Consent for The Sizewell C Project Planning Inspectorate Ref: EN010012 RSPB Registration Identification Ref: 20026628 Suffolk Wildlife Trust Registration Identification Ref: 20026359 The RSPB and SWT Open Floor hearing speech, delivered during OFH 8, Thursday, 20th May Good afternoon Sir. I am Adam Rowlands, Suffolk Area Manager for the RSPB and representing RSPB and Suffolk Wildlife Trust today. I would also like to acknowledge Ben McFarland from Suffolk Wildlife Trust who compiled this presentation with me. I have worked for the RSPB for 30 years and was the Senior Site Manager at RSPB Minsmere from 2004 for 14 years. Thank you for this opportunity to speak today. I will be briefly covering: The history of RSPB and Suffolk Wildlife Trust’s involvement in this area The importance for protected sites and species The wider ecological importance, and; Visitor numbers and wider economic benefits. The RSPB has a long history of involvement with the Suffolk Coast around Sizewell and owns two very significant reserves. North Warren to the south (first purchased in 1939) and Minsmere to the north (where RSPB management commenced in 1947 and land purchase began in 1977). The RSPB currently manages over 1,600 hectares of land for conservation and visitors between Aldeburgh and Walberswick. Minsmere is famous as the site where avocets returned to breed in the UK after a 100 year absence and was also the only site where bearded tits bred in the UK in 1947 and marsh harriers in 1971. -

SBRC Heathland Suffolk State of Nature

Suffolk State of Nature Heathland S.B.R.C. Suffolk State of Nature Heathland 1 Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 2 PART 1: Heathlands 2. Definition of heathland ......................................................................................... 3 3. The Suffolk BAP targets for heathland ................................................................ 4 Definition of terms – maintain, restore, (re)create. 4. The present extent of heathland, and past losses ............................................... 5 Present extent Historical losses – Brecks & Sandlings Parcel size & fragmentation Designation Relationship with other habitats Threats 5. Restoration and re-creation ............................................................................... 14 Present figures on condition of heathland Known restoration and creation projects Lack of reporting / monitoring systems Mapping projects to target creation (Lifescapes & EEHOMP) 6. Monitoring .......................................................................................................... 20 Mapping / monitoring extent Monitoring quality of heathlands (incl species) Monitoring restoration and creation projects / extent BARS 7. Assessment of BAP progress ............................................................................ 22 Summary of key data PART 2: Heathland BAP Species BAP Species associated with Heathland Adder ........................................ Vipera berus ......................................................