View / Open Final Thesis-Vanhorneq.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

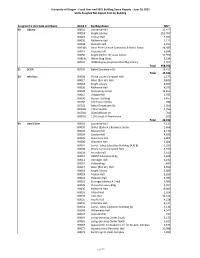

June 30, 2021 Units Assigned Net Square Feet by Building

University of Oregon - Fiscal Year-end 2021 Building Space Reports - June 30, 2021 Units Assigned Net Square Feet by Building Assigned To Unit Code and Name BLDG # Building Name NSF* 20 Library B0001 Lawrence Hall 12,447 B0018 Knight Library 261,767 B0019 Fenton Hall 7,924 B0030 McKenzie Hall 1,112 B0038 Klamath Hall 3,012 B0038A Allan Price Science Commons & Rsch Library 24,383 B0047 Cascade Hall 6,994 B0050 Knight (Wllm. W.) Law Center 31,592 B0814L White Stag Block 5,534 B0903 OIMB Rippey (Loyd and Dorothy) Library 3,997 Total 358,762 21 SCUA B0702 Baker Downtown Ctr 15,422 Total 15,422 30 Info Svcs B0008 Prince LUcien Campbell Hall 1,375 B0017 Allen (Eric W.) Hall 3,826 B0018 Knight Library 8,305 B0030 McKenzie Hall 4,973 B0039 CompUting Center 13,651 B0042 Oregon Hall 2,595 B0090 Rainier BUilding 3,457 B0156 Cell Tower Utility 288 B0702 Baker Downtown Ctr 1,506 B0726L 1715 Franklin 1,756 B0750L 1600 Millrace Dr 700 B0891L 1199 SoUth A WarehoUse 500 Total 42,932 99 Genl Clsrm B0001 Lawrence Hall 7,132 B0002 Chiles (Earle A.) BUsiness Center 2,668 B0003 Anstett Hall 3,176 B0004 Condon Hall 4,696 B0005 University Hall 6,805 B0006 Chapman Hall 3,404 B0007 Lorry I. Lokey EdUcation BUilding (A & B) 2,016 B0008 Prince LUcien Campbell Hall 6,339 B0009 Friendly Hall 2,610 B0010 HEDCO EdUcation Bldg 5,648 B0011 Gerlinger Hall 6,192 B0015 Volcanology 489 B0017 Allen (Eric W.) Hall 4,650 B0018 Knight Library 5,804 B0019 Fenton Hall 3,263 B0022 Peterson Hall 3,494 B0023 Esslinger (ArthUr A.) Hall 3,965 B0029 Clinical Services Bldg 2,467 B0030 McKenzie Hall 19,009 B0031 Villard Hall 1,924 B0034 Lillis Hall 24,144 B0035 Pacific Hall 4,228 B0036 ColUmbia Hall 6,147 B0041 Lorry I. -

Wildcats' Thomas Does It

SATURDAY, MARCH 27, 2021 • SECTION B Editor: Ryan Finley / [email protected] WILDCATS’ THOMAS DOES IT ALL UA needs stat-sheet-stuffing senior to step up in Saturday’s Sweet 16 game vs. Texas A&M PHOTO BY KELLY PRESNELL / ARIZONA DAILY STAR Hansen: Game a battle of Aggies must contend with Familiar faces joining SPORTS SECTION program-building coaches Wildcats’ sensational Sam new ones in Sweet 16 field STARTS ON B9 Arizona’s Barnes, A&M’s Blair crossed Four-year captain Thomas baffles opponents Early upsets have changed the calculus in Check out the Star’s UA paths on their way to the top. B2 with versaility, defensive tenacity. B6-7 a tournament that’s typically chalky. B8 football and softball coverage, and read up on Saturday’s NCAATournament games. B2 NCAA EXTRA SATURDAY, MARCH 27,2021 / ARIZONA DAILYSTAR RESTORATION SPECIALISTS BARNES, BLAIR MEET IN SATURDAY’S SWEET 16 he master builders of the Calipari. Arizona won the WNIT title You get the best shot from T women’s Sweet 16 are Barnes and Blair have every- a day later, Barnes went on to be the super-powers like A&M. Arizona’s Adia Barnes and thing and nothing in common. the Pac-10’s 1998 Player of the How good are the No. 2-seeded Texas A&M’s Gary Blair. They are Barnes is 43. Blair is 75. Barnes Year and the leading scorer in Aggies? They start three Mc- restoration specialists, no job too was a pro basketball player. Arizona history. Blair, then, 50, Donald’s All-Americans: Aaliyah big, too messy or too tiresome. -

Beal Outduels Wall, Wiz Top Rockets

ARAB TIMES, WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 17, 2021 SPORTS 15 Beal outduels Wall, Wiz top Rockets NBA Results/Standings WASHINGTON, Feb 16, (AP): Re- sults and standings from the NBA games on Monday. Washington 131 Houston 119 Chicago 120 Indiana OT 112 New York 123 Atlanta 112 Utah 134 Philadelphia 123 Brooklyn 136 Sacramento 125 LA Clippers 125 Miami 118 Golden State 129 Cleveland 98 Eastern Conference Atlantic Division W L Pct GB Philadelphia 18 10 .643 - Brooklyn 17 12 .586 1-1/2 Boston 13 13 .500 4 New York 14 15 .483 4-1/2 Toronto 12 15 .444 5-1/2 Southeast Division W L Pct GB Charlotte 13 15 .464 - Miami 11 16 .407 1-1/2 Atlanta 11 16 .407 1-1/2 Orlando 10 18 .357 3 Washington 8 17 .320 3-1/2 Central Division W L Pct GB Milwaukee 16 11 .593 - Indiana 14 14 .500 2-1/2 Chicago 11 15 .423 4-1/2 Cleveland 10 19 .345 7 Detroit 8 19 .296 8 Western Conference Southwest Division W L Pct GB San Antonio 16 11 .593 - Memphis 11 11 .500 2-1/2 Dallas 13 15 .464 3-1/2 New Orleans 11 15 .423 4-1/2 Houston 11 16 .407 5 Northwest Division W L Pct GB Utah 23 5 .821 - Portland 16 10 .615 6 Denver 15 11 .577 7 Oklahoma City 11 15 .423 11 Minnesota 7 20 .259 15-1/2 Pacifi c Division W L Pct GB LA Lakers 21 7 .750 - LA Clippers 21 8 .724 -1/2 Phoenix 17 9 .654 3 Golden State 15 13 .536 6 Brooklyn Nets guard Kyrie Irving, (left), keeps the ball out of the reach of Sacramento Kings guard De’Aaron Fox during the second half of an NBA basketball game in Sacramento, Sacramento 12 15 .444 8-1/2 California, on Feb 15. -

Eugene, Cascades & Coast | OREGON

Eugene, Cascades & Coast | OREGON Welcome to Eugene, Cascades & Coast, sports mecca of the Pacific Northwest! Steeped in sports tradition and excellence, we offer multipurpose indoor and outdoor venues, turf and grass fields, and natural outdoor venues with enough flexibility to support most events. Ample, friendly and affordable hotel options, no sales tax and strong local support for all sports makes us the perfect sports destination! PK Park Eugene, Oregon Need Assistance? Once you have selected the Eugene, Cascades & Coast region as your sports event destination, our Sports Services Department will be ready to assist you in planning a successful event. Our experienced staff offers a comprehensive array of services, most of which are complimentary. Promotional materials available include visitor guides, maps, video presentations, high-resolution images, customer web pages and web links for participants. Courtesy of Matthew Knight Arena & UO • Assistance in arranging ground transportation, centralized accommodations and auxiliary space for team meetings, meals and expos. Utilize our knowledge of local vendors for the best referrals from food vendors to printing services. • Permit application guidance • Access to our extensive database of volunteers and local officials • Knowledge of local resources available for use including walkie-talkies, fencing, signs,etc. • Pre- and post-event activities, suggestions and referrals Willamalane Swim Club by Matt Nicholson For personalized assistance, contact Sue Harshbarger Director of Sports Sales & Development [email protected] 541.743.8755 Eugene 08 by Dave Thomas Eugene, Cascades & Coast Sports • 754 Olive St • Eugene OR 97401 • 541.743.8755 • 800.547.5445 • EugeneCascadesCoast.org/sports (US & Canada) Eugene, Cascades & Coast | OREGON Savor Eugene, Cascades & Coast! Soak up the Northwest’s Did you know? laid-back culture with stress-free transportation, affordable • Matthew Knight Arena opened in adventures, plentiful entertainment and authentic experiences. -

Hopkins, DLS, Sauk Centre, Goodhue

WEEKLY ROUNDUP *Lindsay Whalen starred at Hutchinson but fame came later *We pick top 50 players in each class for girls *Transformed Timberwolves Volume 24 Issue No. 1 November 24 2017-2018 Girls No. 1 picks: Hopkins, DLS, Sauk Centre, Goodhue When we last saw the Hopkins girls basketball team, the Royals were battling Elk River in a rare clash of undefeated teams for the state Class 4A championship. Elk River’s senior-dominated lineup won that fierce duel 64-60, but Hopkins was loaded with underclass- men talent and looks like a good bet to cap- ture its seventh state title since 2004 next March. The Minnesota Bas- ketball News pre-sea- son No. 1 teams in the four classes are Hop- Goodhue, celebrating their 2017 title, is the kins, DeLaSalle, Sauk only defending champion ranked No. 1. Centre, and Goodhue. Class 4A Sauk Centre is a Traditional powerhouse Hopkins finds themselves in three-time runner-up, Sophomore star Paige familiar territory as the program to beat in AAAA. The including last year, Bueckers is one of many Royals return four starters from last year’s second- weapons for Hopkins. looking to capture place finisher. Paige Bueckers made the USA 16U Na- that first champion- tional team and traveled to Argentina for international ship. Goodhue will be looking for its third consecutive action this past summer. title. DeLaSalle hopes to recapture the glory of their three-peat of 2011-12-13. Senior veterans Angie Hammond and Raena Suggs along with junior Dlayla Chakolis are bound and deter- The MBBN girls rankings are formulated by Kevin mined to finish the season with gold around their necks. -

Download Magazine

MAGAZINE UCONNSUMMER 2021 finally! They commenced. The classes of 2020 and 2021 gathered at The Rent and made UConn history. In This Issue: FEEDING THE WORLD TURNING YOUR BECOMING THE FIRST AND WINNING THE CHILDHOOD OBSESSION BLACK AMERICAN TO CLIMB NOBEL PEACE PRIZE INTO A HIT PODCAST THE SEVEN SUMMITS SUMMER 2021 SNAP! Husky Home Base The new Husky Athletic Village and Rizza Performance Center includes from right: Elliot Ballpark, home of UConn baseball; Joseph J. Morrone Stadium, home of UConn soccer and lacrosse; Burrill Family Field, home of UConn softball; and shared practice fields. All were in good use this spring, along with indoor facilities, as pandemic rescheduling meant that all 18 UConn sports were actively practicing at the same time. UCONN MAGAZINE | MAGAZINE.UCONN.EDU SUMMER 2021 CONTENTS | SUMMER 2021 SUMMER 2021 | CONTENTS UConn Magazine FROM THE EDITOR VOL. 22 NO. 2 UConn Magazine is produced three times a year (Spring, Summer, and Fall) by University Communications, University of Connecticut. Editor Lisa Stiepock Art Director Christa Yung Photographer Peter Morenus Class Notes Grace Merritt Copy Editors Gregory Lauzon, Elizabeth Omara-Otunnu Designers Yesenia Carrero, Christa Yung UConn Magazine’s art director Christa Yung with her Kirsten doll, circa 2000 (left), and writer Julie Bartucca with her Samantha doll, circa 2021. University Communications 16 20 24 30 Vice President for Communications Tysen Kendig Acting Vice President for ALL DOLLED UP Communications Michael Kirk The pictures above are testament to the truth behind the answer art director Associate Vice President for Creative Christa Yung gave me when I asked her why she was so excited to work with Strategy & Brand Management writer, colleague, and friend Julie Bartucca ’10 (BUS, CLAS), ’19 MBA on the FEATURES SECTIONS Patricia Fazio ’90 (CLAS), ’92 MA American Girls podcast story that begins on page 26. -

Why Aren't You Watching?

“Thrilling WNBA Playoffs Only Given 3% of Sports Spotlight,” by Lindsay Gibbs and Tori Burstein, Power Plays / xx Covering the Coverage. October 22, 2020. xxi “7 Ways to Improve Coverage of Women’s Sports,” by Shira Springer, Nieman Reports. January 7, 2019. “Chasing Equity: The Triumphs, Challenges, and Opportunities in Sports for Girls and Women,” A Women’s Sports xxiii Foundation Research Report, January 2020. Women’s Sports “Basketball’s Growing Gender Wage Gap: The Evidence The WNBA Is Underpaying Players,” by David Berri, Forbes xxiv Magazine. September 20, 2017. xxv “The WNBA’s New CBA, Explained,” by Matt Ellentuck, SB Nation. January 14, 2020. Why Aren’t You Watching? xxvi “NWSL, Players’ Association Pursue First CBA,” AP News, April 7, 2021. xxvii “WNBA Teams Find Success Through Creative Partnerships,” by Bailey Knecht, Front Office Sports. October 10, 2018. “Budweiser’s New Call to Action to Support Women’s Hockey,” by David Brown, The Message: A New Voice for a xxviii New Age of Canadian Marketing. November 7, 2019. “NCAA Withheld Use of Powerful ‘March Madness’ Brand From Women’s Basketball,” By Rachel Bachman, Louise xxix Radnofsky and Laine Higgins, Wall Street Journal. March 22, 2021. “Forbes Top 100 Highest Paid Athletes in the World,” by Kurt Badenhausen, Christina Settimi and Kellen Becoats, xxx Forbes Magazine. May 21, 2020. xxxi “No WNBA Player Has Her Own Shoe, But Why?” by Kelly Whiteside, New York Times. August 26, 2017. xxxii “Becky Sauerbrunn on the first women’s soccer cleats (ever!)” by Megan Ann Wilson, ESPN.com. November 29, 2016. e know a lot has been written about This is a complex issue that will not be solved by women’s sports, especially pertaining one part of the industry. -

Brooks: with Ruffled Ducks Ahead, Buffs Can't Mope

2/11/13 Brooks: With Ruffled Ducks Ahead, Buffs Can’t Mope - CUBuffs.com - Official Athletics Web site of the University of Colorado CU senior Sabatino Chen says the Buffs must have sense of urgency over last nine games. Photo Courtesy: Joel Broida Brooks: With Ruffled Ducks Ahead, Buffs Can’t Mope Release: 02/06/2013 Courtesy: B.G. Brooks, Contributing Editor BOULDER - For most coaches, moving past losses usually requires a couple of days, provided they have a couple to spare. For Tad Boyle, getting rid of last weekend's loss at Utah appeared more of a chore - or so it seemed late Monday Game Notes at Oregon afternoon. He converses weekly (maybe daily during some weeks) with Maryland coach Mark Turgeon, a close friend, mentor and former boss. That Boyle spoke by phone with Turgeon following Colorado's insipid, uninspired 58- 55 loss on Saturday in Salt Lake City was as predictable as discord in Congress. Turgeon's advice to Boyle might seem generic, but after feeling CU's three-game winning streak crumpled and discarded by the Pac-12 Conference's last-place team, any words offered by a colleague/friend were appreciated. Turgeon to Boyle: "Don't get too high, don't get too low; stay even-keeled. That's what he said, and he's right. There were some things I was contemplating that I didn't do (in SLC). But I want our players to understand that the effort and the level of concentration, the level of focus and the level of execution that we displayed against Utah are unacceptable. -

Weed and Banking

LOCALLY OWNED AND OPERATED HAPPY CANNABIS ISSUE! - WE’LL BE YOUR SPOT ALL WEEK FOR - DANK FLOWER SPECIALS 30% OFF ALL REGULAR SHELF BUD COME TRY OUR FINEST STRAINS FOR BUDGET PRICES! $30 OUNCES, AND $3 GRAMS OF SELECT FLOWER, TAX INCLUDED! WHILE SUPPLIES LAST & DOPE DEALS ON CONCENTRATES $10 GRAMS OF SHATTER TAX INCLUDED! WHILE SUPPLIES LAST & $5O ELITE SELECT STRAIN PENTOPS ONLY AT EUGREEN HEALTH CENTER HIGHEST QUALITY LOWEST PRICES SPECIALS VALID MAY 3, 2018 - MAY 9, 2018 Do not operate a vehicle or machinery under the influence of this drug. For use by adults twenty one years of age and older. Keep out of the reach of children. 2 May 3, 2018 • eugeneweekly.com CONTENTS May 3-9, 2018 4 Letters 6 News 10 Slant 12 Cannabis 20 Calendar 29 Movies 30 Music 36 Classifieds 39 Savage Love MISSY SUICIDE WHO YOU GONNA BLAME? editorial Editor Camilla Mortensen Arts Editor Bob Keefer Senior Staff Writer Rick Levin Staff Writer/Web Editor Meerah Powell Calendar Editor Henry Houston Copy Editor Emily Dunnan Social Media Athena Delene Contributing Editor Anita Johnson Contributing Writers Blake Andrews, Ester Barkai, Aaron Brussat, Brett Campbell, Rachael Carnes, Tony Corcoran, Alexis DeFiglia, Jerry Diethelm, Emily Dunnan, Rachel Foster, Mark Harris, William Kennedy, Paul Neevel, Kelsey Anne Rankin, Carl Segerstrom, Ted Taylor, Molly Templeton, Max Thornberry, David Wagner, Robert Warren Interns Taylor Griggs, Taylor Perse Art Department Art Director/Production Manager Todd Cooper Technology/Webmaster James Bateman Graphic Artists Sarah Decker, Chelsea -

Upcoming Eugene Events 2015 Courtesy Reminder on Behalf Of: Hilton Eugene

Upcoming Eugene Events 2015 Courtesy Reminder on Behalf of: Hilton Eugene Eugene Saturday Market Downtown Eugene's First Friday ArtWalk Date(s): Apr 04, 2015 – Nov 14, 2015 Date(s): Jun 05, 2015 – Jul 02, 2015 Recurrence: Every Saturday Recurrence: Recurring daily Times: Saturdays, 10 a.m. - 5 p.m. Times: Daily Location: Downtown Park Blocks (a block away from the Location: Downtown Eugene Hilton) Address: 5th Street to Broadway, Eugene, OR 97401 Address: 126 E. 8th, Eugene, OR 97401 Admission: Free Admission: Free Contact: 541.485.2278 Contact: 541.686.8885 Website: Visit Website Website: Visit Website See displays from local artists all month long at downtown Saturday Market is a weekly celebration of local arts, food, Eugene galleries from 5th Street to Broadway. Visit music and everything Eugene. Over 250 artisans sell their MODERN (207 E 5th Ave), Studio Mantra Salon (40 E 5th handcrafted goods, 16 food booths serve up an international Ave), Belle Sorelle (488 Willamette St), The Lincoln Gallery array of foods, and the stage features 6 live music acts each (309 W 4th Ave), Area 51/50 Clothing (277 W 8th Ave), day. Open rain or shine, in a beautiful park setting. and Raven Frameworks Inc. (325 W 4th Ave). Annual Barrel Tour NCAA Outdoor Track & Field Championships Date(s): Jun 06, 2015 – Jun 20, 2015 Date(s): Jun 10, 2015 – Jun 13, 2015 Recurrence: Every Saturday Recurrence: Recurring daily Times: Saturday Times: Wednesday - Saturday, TBA Location: South Willamette Wineries Association Location: Hayward Field Venue: South Willamette Wineries Association Venue: Hayward Field Admission: TBD Address: 15th and Agate Street, Eugene, OR 97403 Website: Visit Website Admission: Varies Welcome to the Annual Barrel Tour, featuring three unique The nation's best Division I collegiate Track and Field tours of the South Willamette Valley Wineries. -

A All-Time USA Basketball Women's Alphabetical Roster with Affiliation & Results Through February 2020

All-Time USA Basketball Women’s Alphabetical Roster With Affiliation & Results Through February 2020 A NAME AFFILIATION EVENT RECORD / FINISH Katie Abrahamson Georgia 1985 USOF-North 1-3 / Bronze Karna Abram Indiana 1983 USOF-North 1-3 / Fourth Demetra Adams Florida C.C. 1987 USOF-South 2-2 / Silver Jayda Adams Mater Dei H.S. (CA) 2015 U16 4-1 / Bronze Jody Adams Tennessee 1990 JNT 2-2 / N/A 1990 USOF-South 0-4 / Fourth Jordan Adams Mater Dei H.S. (CA) 2011 U19 8-1 / Gold 2010 U17 8-0 / Gold 2009 U16 5-0 / Gold Candice Agee Penn State 2013 U19 9-0 / Gold Silverado H.S. (CA) 2012 U18 5-0 / Gold Valerie Agee Hawaii 1991 USOF-West 1-3 / Bronze Matee Ajavon Rutgers 2007 PAG 5-0 / Gold Malcom X Shabazz H.S. (NJ) 2003 YDF-East 5-0 / Gold Bella Alarie Princeton 2019 PAG 4-1 / Silver 2017 U19 6-1 / Silver Tawona Al-Haleem John A. Logan College 1993 USOF-North 2-2 / Bronze Moniquee Alexander IMG Academy (FL) 2005 YDF-Red 3-2 / Bronze Rita Alexander Hutcherson Flying Queens / 1957 WC 8-1 / Gold Wayland Baptist College 1955 PAG 8-0 / Gold Danielle Allen Harrison H.S. (AR) 2002 YDF-South 2-3 / Silver Lindsay Allen St. John's College H.S. (DC) 2012 U17 8-0 / Gold Sha'Ronda Allen Western Kentucky 1995 USOF-North 2-2 / Bronze Starretta Allen Independence H.S. (OH) 2004 YDF-North 2-3 / Silver Britney Anderson Meadowbrook H.S. (VA) 2002 YDF-East 3-2 / Bronze Chantelle Anderson Vanderbilt 2001 WUG 7-1 / Gold 2000 JCUP 4-0 / Gold 2000 SEL Lost / 97-31 Hudson Bay H.S. -

Duck Men's Basketball

ATHLETIC COMMUNICATIONS (MBB) Greg Walker [email protected] O: 541-346-2252 C: 541-954-8775 Len Casanova Center | 2727 Leo Harris Parkway | @OregonMBB | Facebook.com/OregonMBB | GoDucks.com 2020-21 SCHEDULE DUCK MEN’S BASKETBALL NOVEMBER RESULT SCORE No. 21 OREGON (9-2, 4-1) vs. OREGON STATE (7-5, 3-3) 25 Eastern Washington PPD PPD Date Saturday, January 23, 2021 Tip Time 7:35 p.m. PT DECEMBER RESULT SCORE Site / Stadium / Capacity Eugene, Ore. / Matthew Knight Arena / 12,364 2 vs. Missouri 1 L 75-83 Television Pac-12 Network 4 vs. Seton Hall 1 W 83-70 Ted Robinson, play-by-play; Don MacLean, analyst Radio Oregon Sports Network (95.3 FM KUJZ in Eugene/Springfi eld) 7 Eastern Washington W 69-52 Joey McMurry, play-by-play; Jerry Allen, analyst 9 Florida A&M W 87-66 Live Stats GoDucks.com Live Audio GoDucks.com 12 at Washington * W 74-71 Twitter @OregonMBB 17 San Francisco W 74-64 Internet tunein.com 19 Portland W 80-41 Satellite Radio Sirius ch. 146 / XM ch. 197 / Internet 959 23 UCLA * PPD PPD SERIES HISTORY 31 California * W 82-69 All-Time Oregon State leads, 190-164 Last Meeting Oregon 69, Oregon State 54, Feb. 27, 2020 (Eugene, Ore.) JANUARY TIME TV Current Streak Ducks +1 2 Stanford * W 73-56 Last Oregon Win Oregon 69, Oregon State 54, Feb. 27, 2020 (Eugene, Ore.) Last OSU Win Oregon State 63, Oregon 53, Feb. 8, 2020 (Corvallis, Ore.) 7 at Colorado * L 72-79 9 at Utah * W 79-73 THE STARTING 5 14 Arizona State * PPD PPD 16 Arizona * PPD PPD No.