Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brevard Indian Classical Music Society Presents Sitar, Santoor & Tabla

brEVard iNdiaN ClaSSiCal MUSiC SoCiEty PrESENtS Sitar, SaNtoor & tabla Sponsored by BIMDA Event Chair: Subhash Rege, Mahesh Soni, Gladwyn Kurian SaNtoor Sitar tabla Nandkishor Muley Dr. Kanada Narahari Shankh Lahiri VENUE Brevard Hindu Mandir 1517 Avenida del Rio Melbourne, FL 32901 Date: Saturday, April 10th Program Starts: 4:30 pm Dinner: 7:45 pm MANDATORY Covid-19 Vaccination required to attend ... FREE to all Members PLEASE RSVP > BIMDA Email Invitation Brevard IndIan ClassICal MusIC soCIety Presents Nandkishor Muley SaNtoor Santur (Santoor) maestro Nandkishor Muley is considered the leading performer of this ancient, delicate instrument from the vibrant land of India. Nandkishor comes from a long lineage of musicians. Educated early in vocals and Tabla from his father Dattatraya and uncle Shrikant Muley. He is holding Masters degree in Indian music and Kathak dance from M.S. University of Baroda. Nandkishor had already received acclaim in India before entering study on the Santur with Pundit Shivkumar Sharma, which led to his current high esteem as a principal figure in Indian music. Nandkishor has been accredited with German Grammy Award, the famous ìSurmaniî award, the Excellence Art and Cultural Educator award from United Arts of Florida (USA), just to name a few. Nandkishor is widely travels different parts of world for his musical performances. His lectures and workshops on Indian Vocal & Instrumental classical music are highly educative to enrich learners & artists. He is an adjunct professor of Indian music and dance at Stetson University and University Of Central Florida (UCF) in Orlando. Florida. Brevard IndIan ClassICal MusIC soCIety Presents Dr. Kanada Narahari Sitar Dr Kanada Narahari (Kanada Raghava) was born in Manchikeri, a small village in western ghats, Karnataka, India to his illustrious parents, Vidvan Narahari Keshava Bhat and Sumangala Bhat. -

Stephen M. Slawek Curriculum Vitae

Stephen M. Slawek Curriculum Vitae 10008 Sausalito Drive Butler School of Music Austin, TX 78759-6106 The University of Texas at Austin (512) 794-2981 Austin, TX. 78712-0435 (512) 471-0671 Education 1986 Ph.D. (Ethnomusicology) University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1978 M.A. (Ethnomusicology) University of Hawaii at Manoa 1976 M. Mus. (Sitar) Banaras Hindu University 1974 B. Mus. (Sitar) Banaras Hindu University 1973 Diploma (Tabla) Banaras Hindu University 1971 B.A. (Biology) University of Pennsylvania Employment 1999-present Professor of Ethnomusicology, The University of Texas at Austin 2000 Visiting Professor, Rice University, Hanzsen and Lovett College 1989-1999 Associate Professor of Ethnomusicology and Asian Studies, The University of Texas at Austin 1985-1989 Assistant Professor of Ethnomusicology and Asian Studies, The University of Texas at Austin 1983-1985 Instructor of Ethnomusicology and Asian Studies, The University of Texas at Austin 1983 Visiting Lecturer of Ethnomusicology, University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign 1982 Graduate Assistant, School of Music, University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign 1978-1980 Archivist, Archives of Ethnomusicology, School of Music, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Scholarship and Creative Activities Books under contract The Classical Music of India: Going Global with Ravi Shankar. New York and London: Routledge Press. 1997 Musical Instruments of North India: Eighteenth Century Portraits by Baltazard Solvyns. Delhi: Manohar Publishers. Pp. i-vi and 1-153. (with Robert L. Hardgrave) SLAWEK- curriculum vitae 2 1987 Sitar Technique in Nibaddh Forms. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, Indological Publishers and Booksellers. Pp. i-xix and 1-232. Articles in scholarly journals 1996 In Raga, in Tala, Out of Culture?: Problems and Prospects of a Hindustani Musical Transplant in Central Texas. -

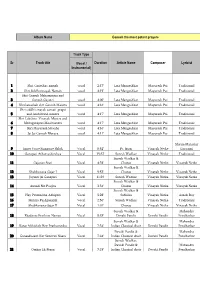

Album Name Ganesh the Most Potent Prayers Sr Track Title Track Type

Album Name Ganesh the most potent prayers Track Type Sr Track title (Vocal / Duration Artiste Name Composer Lyricist Instrumental) 1 Shri Ganeshay namah vocal 2:17' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional 2 Shri Siddhivinayak Naman vocal 4:15' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional Shri Ganesh Mahamantra and 3 Ganesh Gayatri vocal 4:00' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional 4 Kleshanashak shri Ganesh Mantra vocal 4:16' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional Shri siddhivinayak santati-prapti 5 and Aashirvaad mantra vocal 4:17' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional Shri Lakshmi-Vinayak Mantra and 6 Mahaganapati Moolmantra vocal 4:17' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional 7 Shri Mayuresh Stavaha vocal 4:16' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional 8 Jai Jai Ganesh Moraya vocal 4:11' Lata Mangeshkar Mayuresh Pai Traditional Shyam Manohar 9 Inner Voice Signature Shlok Vocal 0:52' Pt. Jasraj Vinayak Netke Goswami 10 Ganapati Atharvashirshya Vocal 15:37' Suresh Wadkar Vinayak Netke Traditional Suresh Wadkar & 11 Gajanan Stuti Vocal 4:35' Chorus Vinayak Netke Vinayak Netke Suresh Wadkar & 12 Shubhanana Gajar I Vocal 5:53' Chorus Vinayak Netke Vinayak Netke 13 Jayanti jai Ganapati Vocal 11:39' Suresh Wadkar Vinayak Netke Vinayak Netke Suresh Wadkar & 14 Anaadi Nit Poojita Vocal 3:34' Chorus Vinayak Netke Vinayak Netke Suresh Wadkar & 15 Hey Prarambha Adhipati Vocal 5:28' Sabhiha Vinayak Netke Ashok Roy 16 Mantra Pushpaanjali Vocal 2:56' Suresh Wadkar Vinayak Netke Traditional 17 Shubhanana Gajar II Vocal 1:01' Chorus Vinayak Netke -

APL Details Unclaimed Unpaid Interim Dividend F.Y. 2019-2020

ALEMBIC PHARMACEUTICALS LIMITED STATEMENT OF UNCLAIMED/UNPAID INTERIM DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2019‐20 AS ON 6TH APRIL, 2020 (I.E. DATE OF TRANSFER TO UNPAID DIVIDEND ACCOUNT) NAME ADDRESS AMOUNT OF UNPAID DIVIDEND (RS.) MUKESH SHUKLA LIC CBO‐3 KA SAMNE, DR. MAJAM GALI, BHAGAT 200.00 COLONEY, JABALPUR, 0 HAMEED A P . ALUMPARAMBIL HOUSE, P O KURANHIYOOR, VIA 900.00 CHAVAKKAD, TRICHUR, 0 RAJESH BHAGWATI JHAVERI 30 B AMITA 2ND FLOOR, JAYBHARAT SOCIETY 3RD ROAD, 750.00 KHAR WEST MUMBAI 400521, , 0 NALINI NATARAJAN FLAT NO‐1 ANANT APTS, 124/4B NEAR FILM INSTITUTE, 1000.00 ERANDAWANE PUNE 410004, , 0 ANURADHA SEN C K SEN ROAD, AGARPARA, 24 PGS (N) 743177, , 0 900.00 SWAPAN CHAKRABORTY M/S MODERN SALES AGENCY, 65A CENTRAL RD P O 900.00 NONACHANDANPUKUR, BANACKPUR 743102, , 0 PULAK KUMAR BHOWMICK 95 HARISHABHA ROAD, P O NONACHANDANPUKUR, 900.00 BARRACKPUR 743102, , 0 JOJI MATHEW SACHIN MEDICALS, I C O JUNCTION, PERUNNA P O, 1000.00 CHANGANACHERRY, KERALA, 100000 MAHESH KUMAR GUPTA 4902/88, DARYA GANJ, , NEW DELHI, 110002 250.00 M P SINGH UJJWAL LTD SHASHI BUILDING, 4/18 ASAF ALI ROAD, NEW 900.00 DELHI 110002, NEW DELHI, 110002 KOTA UMA SARMA D‐II/53 KAKA NAGAR, NEW DELHI INDIA 110003, , NEW 500.00 DELHI, 110003 MITHUN SECURITIES PVT LTD 1224/5 1ST FLOOR SUCHET CHAMBS, NAIWALA BANK 50.00 STREET, KAROL BAGH, NEW DELHI, 110005 ATUL GUPTA K‐2,GROUND FLOOR, MODEL TOWN, DELHI, DELHI, 1000.00 110009 BHAGRANI B‐521 SUDERSHAN PARK, MOTI NAGAR, NEW DELHI 1350.00 110015, NEW DELHI, 110015 VENIRAM J SHARMA G 15/1 NO 8 RAVI BROS, NR MOTHER DAIRY, MALVIYA 50.00 -

More Than Just a Tabla Wizard

«» FR1DAYREV1EW SPOTLIGHT FRIDAY, JANUARY 25, 2019 ft **3C In 1974, he formed the group Traya with his sons Nayan and Druba (a sarangi player), and per formed and conducted lec-dems at universities across the globe. "During his extensive travels, he developed a close rapport with iconic musicians such as Ye- hudi Menuhin, Benjamin Britten, Larry Adler, Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and Dave Bru- beck," says Nayan. Wide perspective More than "My father would make us (sister Tulika is a trained vocalist) listen to Beethoven, Bach and Ameri can Country music. He hated just a tabla building boundaries around art. He would say open-mindedness is the way forward in life. Some one who believed in wholesome wizard development of personality, he didn't let us give up academics because we were into music. He Pt Nikhil Ghosh was a even encouraged us to pursue arati, originally known as Arun gan on December 11 with the in er's versatility. Known more as a sports. He was an athlete, while vocalist, percussionist, Sangeetalaya, was established in imitable Ustad Zakir Hussain's sitar and tabla exponent, Nayan my uncle (Pannalal Ghosh) was a educator, author and 1956. Twelve years later, it moved Taalanjali at the Nehru Centre in Ghosh is an equally skilled vocal researcher. The maestro's to the present premises. Mumbai, followed by Kathak ace ist, who also plays the surbahar Last week (January 17 to 20), Pt. Birju Maharaj's performance. and pakhawaj. Nayan's son Ish- musician-son Nayan Ghosh Sangeet Mahabharati bustled Born in Barisal in East Bengal aan is also a tabla artiste. -

Booklet (Adobe Acrobat Format)

N G L A A C M : M G RAGA RECORDS Nayan Ghosh on Shree Rag Ira Landgarten: People sometimes have different descriptions or interpretations of a rag — it’s implications, it’s mood, the way it’s performed — that’s why we’d like to hear specifically about Shree rag directly from you. Nayan Ghosh: Shree rag is definitely one of the most revered among ragas. It has a gravity, an intensity that is really difficult to match. The rag itself has a very strong inherent strength. It is a dusk-time rag. My uncle (Pannalal Ghosh) was one of the two or three artists who were almost synonymous with Shree Rag; the others being Ustad Ali Akbar Khan and D.V. Paluskar. My father used to mention about his meetings with Mamman Khan, the uncle of the Sarangi legend Bundu Khan. Mamman Khan always brought in references of Shree Rag to whatever he spoke about. That was everything for him. The Shree Rag as my father taught me — he used to teach me more the alaps and the actual rag, and the first time I received my training in Shree Rag was very interesting. It was at a hill station near Bombay; no cars go up it, you have to walk all over the hill station. There are ponies and hand-pulled rickshaws and all that. It’s a beautiful hill station and one evening he took us to an edge of that hill station, on the cliff, and we were facing the west side and in front of us between our mountain and the opposite one was a deep valley down. -

Dual Edition

YEARS # 1 Indian American Weekly : Since 2006 VOL 15 ISSUE 13 ● NEW YORK / DALLAS ● MAR 26 - MAR 25 - APR 01, 2021 ● ENQUIRIES: 646-247-9458 ● [email protected] www.theindianpanorama.news THE INDIAN PANORAMA ADVT. FRIDAY MARCH 26, 2021 YEARS 02 We Wish Readers a Happy Holi YEARS # 1 Indian American Weekly : Since 2006 VOL 15 ISSUE 13 ● NEW YORK / DALLAS ● MAR 26 - MAR 25 - APR 01, 2021 ● ENQUIRIES: 646-247-9458 ● [email protected] www.theindianpanorama.news VAISAKHI SPECIAL EDITIONS Will Organize Summit of will bring out a special edition tomarkVAISAKHIon April 9. Democracies, says Biden Advertisementsmay please be booked by April 2, andarticles for publication may please besubmitted by March 30 to [email protected] "We've got to prove democracy works," he said. I.S. SALUJA First historic Mars WASHINGTON (TIP): President Joe Biden shared with media persons his helicopter flight on April 8: thoughts on a wide range of issues, and NASA also candidly answered their questions, March 25, at his first press conference The flight since assuming office on January model of NASA's 20.2021. Ingenuity During the press conference, Mr. Mars Biden remarked on and responded to Helicopter - questions regarding migrants at the Image: NASA / JPL U.S.-Mexico border, the COVID-19 contd on page 48 WASHINGTON (TIP): NASA will U.S. President Joe Biden holds his first formal attempt to fly Ingenuity mini << news conference as president in the East helicopter, currently attached to the Room of the White House in Washington, U.S., belly of Perseverance rover, on Mars March 25, 2021. -

DU MA Percussion Music

DU MA Percussion Music Topic:- DU_J19_MA_PM 1) Which of the following is not a Yati? इनमे से कौन यत नहं ह? [Question ID = 213] 1. Pipilika / पपीलका [Option ID = 850] 2. Mridanga / मदृ ंगा [Option ID = 849] 3. Anagat / अनागत [Option ID = 852] 4. Sama / समा [Option ID = 851] Correct Answer :- Mridanga / मदृ ंगा [Option ID = 849] 2) Which artist was famous for ‘Dance Accompaniment? नयृ के साथ संगत करने म कौन से कलाकार स थे? [Question ID = 186] 1. Pt. Pagal Das / पं. पागल दास [Option ID = 742] 2. Pt. Birju Maharaj / पं. बरज ू महाराज [Option ID = 743] 3. Pt. Kudau Singh / पं. कु दऊ सहं [Option ID = 744] 4. Pt. Kishan Maharaj / पं. कशन महाराज [Option ID = 741] Correct Answer :- Pt. Kishan Maharaj / पं. कशन महाराज [Option ID = 741] 3) Which gharana plays with variation of ‘Theka’ ? ‘ठेके ’ के वतार के साथ कस घराने का वादन होता है:- [Question ID = 215] 1. Delhi gharana / दल घराना [Option ID = 857] 2. Ajrada Gharana / अजराड़ा घराना [Option ID = 858] 3. Banaras Gharana / बनारस घराना [Option ID = 860] 4. Lucknow gharana / लखनऊ घराना [Option ID = 859] Correct Answer :- Delhi gharana / दल घराना [Option ID = 857] 4) Which Gharana is influenced by the compositions of Pakhawaj ? कौन सा घराना पखावज़ क बंदश से भावत है? [Question ID = 249] 1. Delhi / दल [Option ID = 993] 2. Ajrada / अजराड़ा [Option ID = 996] 3. -

Performing Modernity Musicophilia in Bombay/Mumbai

TISS Working Paper No. 3 March 2013 PERFORMING MODERNITY MUSICOPHILIA IN BOMBAY/MUMBAI TEJASWINI NIRANJANA Research and Development Tata Institute of Social Sciences © Tata Institute of Social Sciences TISS Working Paper No. 3, March 2013 Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................1 Musicophilia and Modernity .............................................................................................................3 Studying Music in Bombay ...............................................................................................................5 Theatre and Hindustani Music ..........................................................................................................6 Musical Pedagogy ..............................................................................................................................7 Lingua Musica ...................................................................................................................................9 References .......................................................................................................................................11 Additional Data Sources ..................................................................................................................13 Appendix I ......................................................................................................................................14 iii iv ABSTRACT This -

Detailed Catalog

Last Update QUESTZ WORLD January 2017 Address : K304 Binayak Enclave, 59 K C G Road, Kolkata 700050 Mobile : (+91) 90516-72666 Email : [email protected] / [email protected] Web : www.questz.world Corporate Web : www.w2n.co PRODUCT ARTISTS PRODUCT TITLES TRACK DETAILS CODES MRP (INR) MRP (USD) # Indian Classical Music ## SITAR Nikhil Banerjee (Sitar) & Sankha Chatterjee (Tabla) Hemant Alap, Jor, Jhala Q-MI-CJ-010 200 15 Vilambit & Drut In Teen Taal Nikhil Banerjee (Sitar) & Swapan Chaudhuri (Tabla) Gauri Manjari Alap, Jor, Jhala Q-MI-CJ-038 200 15 Vilambit In Teen Taal Drut In Ek Taal Nikhil Banerjee (Sitar) & Anindo Chatterjee (Tabla) Lalita Gauri Alap, Jor, Jhala QW-IC-007 200 15 Vilambit In Pancham Sawari Taal Drut In Teen Taal Vilayat Khan (Sitar) & Sankha Chatterjee (Tabla) Aftab-E-Sitar Bageshri (Alap, Jor, Jhala, Gats In Teen Taal) Q-MI-CJ-028 200 15 Tilok Kamod & Bihari (Alap In Tilok Kamod, Gats In Bihari In Teen Taal) Vilayat Khan (Sitar) & Samta Prasad (Tabla) Yamani Alap, Jor, Jhala QW-IC-009 200 15 Vilambit In Teen Taal Drut In Teen Taal Mushtaq Ali Khan (Sitar+Surbahar) & Keramutulla Khan (Tabla) + Video Documentary On Him Birth Centenary Tribute (CD+DVD) Shudh Basant (Surbahar) Q-MI-CA-039 300 21 Kedar (Sitar) Hindol (Sitar) Video Documentary In DVD Mushtaq Ali Khan (Sitar) & Keramutulla Khan (Tabla) Sitar Sudhakar Darbari Kanada Q-MI-CJ-040 200 15 Bihag Bhairavi Santosh Banerjee (Sitar+Surbahar) & Amit Banerjee (Tabla) Lilting Legacy (Double Audio-CD) Surbahar CD - Abhogi Kanada Q-MI-CJ-048 300 21 Surbahar CD - Darbari Kanada Sitar -

Jamshed Bhabha Memorial Lecture an Ode to the Arts

August 2019 ON Stagevolume 9 • issue 1 Jamshed Bhabha Memorial Lecture An ode to the arts NCPA BANDISH A Tribute to Legendary Composers AUTUMN 2019 SEASON Stravinsky and Tchaikovsky Cover Final.indd 1 16/07/19 4:58 PM NCPA Chairman Khushroo N. Suntook Editorial Director Radhakrishnan Nair Editor-in-Chief Oishani Mitra Contents Consulting Editor Vipasha Aloukik Pai Editorial Co-ordinator 18 Hilda Darukhanawalla Art Director Tanvi Shah Associate Art Director Hemali Limbachiya Advertising Anita Maria Pancras ([email protected]; 66223835) Tulsi Bavishi ([email protected]; 9833116584) Senior Digital Manager Jayesh V. Salvi Produced by Editorial Office 4th Floor, Todi Building, Mathuradas Mills Compound, Senapati Bapat Marg, Lower Parel, Mumbai - 400013 Printer Spenta Multimedia, Peninsula Spenta, Mathuradas Mill Compound, N. M. Joshi Marg, Lower Parel, Features Mumbai – 400013 Materials in ON Stage cannot be reproduced in part or whole without the written permission shine the spotlight on the legacies of the publisher. Views and opinions expressed 08 of two trailblazing artistes – Kumar in this magazine are not necessarily those of Reflections Gandharva and Jnan Prakash Ghosh. the publisher. All rights reserved. Statues of Limitations. By Anil Dharker We try to find out how both these NCPA Booking Office men had the impulse, as musicians, to 2282 4567/6654 8135/6622 3724 follow the heart instead of the rules. www.ncpamumbai.com 10 By Reshma O. Pathare A Commemorative Conclave Dr. Jamshed Bhabha’s life was one filled with and dedicated to the arts. Fittingly, the NCPA has decided to have an annual 18 lecture series on his birthday that focusses An orchestra for all seasons on art and culture. -

Working-PDF Converter.Xlsx

Hospital Active list for Good Health Insurance TPA Limited as on 19th Aug 2021. Sr. No State City Hospital Name Address Pin Code Contact 1 Andaman And Nicobar Port Blair Dr. Agarwal's Eye Hospital LTD Near Radha Govind Temple, Rgt Road, 744106 03192-244222 12-2-939, Beside State Bank of India,3rd Cross Sai 2 Andhra Pradesh Anantapur Hrudaya Childrens Hospital 515001 0855-4274471 Nagar, 3 Andhra Pradesh Anantapur S V hospital (A unit of Ameya Healthcare Alliance) 14-327, Kamala Nagar, 515001 08554-221966 13-3-510, Opp. Ganga Gowri Cine Complex,Khaja 4 Andhra Pradesh Anantapur Snehalatha Hospitals 515001 08554-277077 Nagar, Ananthapuram District, D.No.11/1/234,3Rd Cross Aravinda 5 Andhra Pradesh Anantapur Sree Amaravathi Multi Speciality Hospital 515001 08554-231567 Nagar,Ananthapuramu, 13-3-488, Near Ganga-Gowricine 6 Andhra Pradesh Anantapur Sreenivasa Childrens Hospital 515001 0855-4241104 Complex,Sreekantan Circle, 7 Andhra Pradesh Anantapur Vasan Eye Care Hospital - Anantapur Street Raju Road ,Anantapur, 515001 0855-4222445/302100 8 Andhra Pradesh Anantapuram Dr Ysr Memorial Hospital 1ST Cross, Sai Nagar, 515001 8554232727 9 Andhra Pradesh Badvel Padmavathi Hospital D No, 6-2-4/1, Sumithra Nagar,Siddavatam Road, 516227 08569266533 10 Andhra Pradesh Bhimavaram Varma Hospitals JP Road, Suryanarayana puram, 534202 9848699996 11 Andhra Pradesh Chilakaluripeta Rama krishna Memorial Nursing Home Bhaskar Theatre Centre, Chilakaluripeta, 522616 9912300697 1-653/3, Opp Kannan Kalyanamandapam, 12 Andhra Pradesh Chittoor Aashraya Multi specialty Hospital 517001 08572-246544 Kattamanchi, Chittoor, 13 Andhra Pradesh Eluru Andhra Hospital (Eluru) Pvt. Ltd. D No 23A 8-8 ,Behndaprdari street,R.