Forms of Time: Unity in Plurality Jirˇ´I Wackermann Dept

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ijet.V14i18.10763

Paper—Anytime Autonomous English MALL App Engagement Anytime Autonomous English MALL App Engagement https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v14i18.10763 Jason Byrne Toyo University, Tokyo, Japan [email protected] Abstract—Mobile assisted language learning (MALL) apps are often said to be 'Anytime' activities. But, when is 'Anytime' exactly? The objective of the pa- per is to provide evidence for the when of MALL activity around the world. The research method involved the collection and analysis of an EFL app’s time data from 44 countries. The findings were surprising in the actual consistency of us- age, 24/7, across 43 of the 44 countries. The 44th country was interesting in that it differed significantly in terms of night time usage. The research also noted differences in Arab, East Asian and Post-Communist country usage, to what might be construed to be a general worldwide app time usage norm. The results are of interest as the time data findings appear to inform the possibility of a po- tentially new innovative pedagogy based on an emerging computational aware- ness of context and opportunity, suggesting a possible future language learning niche within the Internet of Things (IoT), of prompted, powerful, short-burst, mobile learning. Keywords—CALL, MALL, EFL, IoT, Post-Communist, Saudi Arabia. 1 Introduction 'Learning anytime, anywhere' is one of the most well-known phrases used to de- scribe learning technology [1]. A review of the Mobile Assisted Language Learning (MALL) literature will rapidly bring forth the phrase 'Anytime and anywhere.' But, when exactly is anytime? Is it really 24/7? Or, is it more nuanced? For example, does it vary from country to country, day by day or hour by hour? The literature simply does not provide answers. -

Simulating Dynamic Time Dilation in Relativistic Virtual Environment

International Journal of Computer Theory and Engineering, Vol. 8, No. 5, October 2016 Simulating Dynamic Time Dilation in Relativistic Virtual Environment Abbas Saliimi Lokman, Ngahzaifa Ab. Ghani, and Lok Leh Leong table showing all related activities needed to produce the Abstract—This paper critically reviews several Special objective simulation which is a dynamic Time Dilation effect Relativity simulation applications and proposes a method to in relativistic virtual environment. dynamically simulate Time Dilation effect. To the authors’ knowledge, this has not yet been studied by other researchers. Dynamic in the context of this paper is defined by the ability to persistently simulate Time Dilation effect based on specific II. LITERATURE ON TIME DILATION SIMULATION parameter that can be controlled by user/viewer in real-time A lot of effort to visualize Special Relativity using interactive simulation. Said parameter is the value of speed graphical computerize simulation have been done throughout from acceleration and deceleration of moving observer. In recent years [1]-[7]. Most of them focused on visualizing relativistic environment, changing the speed’s value will also change the Lorentz Factor value thus directly affect the Time relativistic environment from the effect of Lorentz Dilation value. One can simply calculate the dilated time by Transformation. Although it is rare, there is also an attempt to using Time Dilation equation, however if the velocity is not simulate Lorentz Transformation effect in “real world” constant (from implying Special Relativity), one must setting by warping real world camera captured images [8]. repeatedly calculate the dilated time considering the changing Time Dilation however did not get much attention. -

BAR926HG.Pdf

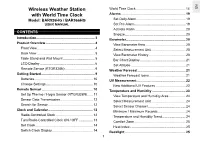

Wireless Weather Station World Time Clock .....................................................14 EN with World Time Clock Alarms ..................................................................... 19 Model: BAR926HG / BAR966HG Set Daily Alarm ..................................................... 19 USER MANUAL Set Pre-Alarm ....................................................... 19 Activate Alarm ...................................................... 20 CONTENTS Snooze ................................................................. 20 Introduction ............................................................... 3 Barometer ................................................................ 20 Product Overview ..................................................... 4 View Barometer Area ........................................... 20 Front View .............................................................. 4 Select Measurement Unit ..................................... 20 Back View .............................................................. 5 View Barometer History ....................................... 20 Table Stand and Wall Mount .............................. 5 Bar Chart Display ................................................. 21 LCD Display ........................................................... 6 Set Altitude ........................................................... 21 Remote Sensor (RTGR328N) ................................ 9 Weather Forecast ................................................... 21 Getting Started ......................................................... -

Kronosync® Transmitter Operations Guide

KRONOsync Transmitter System Operations Guide 11869 Teale St. Culver City, CA 90230 Tech Support: 888-608-0125 www.InnovationWireless.com System Operations Guide Thank You for Purchasing the KRONOsync GPS/NTP Wireless Clock System from Innovation Wireless. We appreciate having you as a customer and wish you many years of satisfied use with your KRONOsync clock system. Innovation Wireless has incorporated our 40+ years of experience in clock manufacturing with the best of today’s innovative technology into the KRONOsync system. The result being an accurate, reliable, ‘Plug and Play’, wireless clock system for your facility. Please read this manual thoroughly before making any connections and powering up the transmitter. Following these instructions will enable you to obtain optimum performance from the KRONOsync Wireless Clock System. If you have any questions during set-up, please contact Technical Support at 1-888-608-0125. Thank you again for your purchase. From all of us at Innovation Wireless 2 | P a g e Innovation Wireless System Operations Guide System Operations Guide Table of Contents KRONOsync Transmitter Set-up .................................................................................................................... 4 Mounting the GPS Receiver .......................................................................................................................... 4 Connecting the NTP Receiver........................................................................................................................ 4 Power -

User Guide 2.0

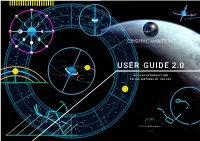

NORTH CELESTIAL POLE Polaris SUN NORTH POLE E Q U A T O R C SOUTH POLE E L R E S T I A L E Q U A T O EARTH’S AXIS EARTH’S SOUTH CELESTIAL POLE USER GUIDE 2.0 WITH AN INTRODUCTION 23.45° TO THE MOTIONS OF THE SKY meridian E horizon W rise set Celestial Dynamics Celestial Dynamics CelestialCelestial Dynamics Dynamics CelestialCelestial Dynamics Dynamics 2019 II III Celestial Dynamics Celestial Dynamics FULLSCREEN CONTENTS SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS VI SKY SETTINGS 24 CONSTELLATIONS 24 HELP MENU INTRODUCTION 1 ZODIAC 24 BASIC CONCEPTS 2 CONSTELLATION NAMES 24 CENTRED ON EARTH 2 WORLD CLOCKASTRONOMYASTROLOGY MINIMAL STAR NAMES 25 SEARCH LOCATIONS THE CELESTIAL SPHERE IS LONG EXPOSURE 25 A PROJECTION 2 00:00 INTERSTELLAR GAS & DUST 25 A FIRST TOUR 3 EVENTS & SKY GRADIENT 25 PRESETS NOTIFICATIONS LOOK AROUND, ZOOM IN AND OUT 3 GUIDES 26 SEARCH LOCATIONS ON THE GLOBE 4 HORIZON 26 CENTER YOUR VIEW 4 SKY EARTH SOLAR PLANET NAMES 26 SYSTEM ABOUT & INFO FULLSCREEN 4 CONNECTIONS 26 SEARCH LOCATIONS TYPING 5 CELESTIAL RINGS 27 ADVANCED SETTINGS FAVOURITES 5 EQUATORIAL COORDINATES 27 QUICK START QUICK VIEW OPTIONS 6 FAVOURITE LOCATIONS ORBITS 27 VIEW THE USER INTERFACE 7 EARTH SETTINGS 28 GEOCENTRIC HOW TO EXIT 7 CLOUDS 28 SCREENSHOT PRESETS 8 HI -RES 28 POSITION 28 HELIOCENTRIC WORLD CLOCK 9 COMPASS CELESTIAL SPHERE SEARCH LOCATIONS TYPING 10 THE MOON 29 FAVOURITES 10 EVENTS & NOTIFICATIONS 30 ASTRONOMY MODE 15 SETTINGS 31 VISUAL SETTINGS ASTROLOGY MODE 16 SYSTEM NOTIFICATIONS 31 IN APP NOTIFICATIONS 31 MINIMAL MODE 17 ABOUT 32 THE VIEWS 18 ADVANCED SETTINGS 32 SKY VIEW 18 COMPASS ON / OFF 19 ASTRONOMICAL ALGORITHMS 33 EARTH VIEW 20 SCREENSHOT 34 CELESTIAL SPHERE ON / OFF 20 HELP 35 TIME CONTROL SOLAR SYSTEM VIEW 21 FINAL THOUGHTS 35 GEOCENTRIC / HELIOCENTRIC 21 TROUBLESHOOTING 36 VISUAL SETTINGS 22 CONTACT 37 CLOCK SETTINGS 22 ASTRONOMICAL CONCEPTS 38 ECLIPTIC CLOCK FACE 22 EQUATORIAL CLOCK FACE 23 IV V INTRODUCTION SYSTEM REQUIREMENTS The Cosmic Watch is a virtual planetarium on your mobile device. -

The World's Finest Timepiece Tells More Than Just Time

The world’s finest timepiece tells more than just time. The Geochro n® World Clock. {It also tells the world something about you.} They have adorned the offices of the world’s largest organisations. The walls of private yachts and aircraft. The homes of the wealthy. They are the prized possession of discerning individuals who need to know more than just the local time. Handmade, each Geochron is a moving masterpiece. It shows you at a glance the current time of the world — every country and city — within a mesmerising display of the progression of daylight around the Earth. A Geochron is your world view of day and night, the precise time, the date and day of the week — even the solstices and equinoxes. All without a single digital component. Each clock is carefully crafted and calibrated for unparalleled accuracy and precision. Beautiful, unique, pristine and of the highest quality, a Geochron is much more than a clock. You’ll be the owner of what the Smithsonian Institution calls “the last significant contribution in time keeping.” Map – Each world map is made Minute dial – (Optional) Offers using state-of-the-art lithographic the time to the minute in any printing designed to ensure the city in the world. map’s vibrancy and sharpness for the lifetime of the clock. Terminator line – Displays true moment of sunrise and sunset worldwide. Time scale – The “watch” of the timepiece. As the map rotates, numbers reveal the corresponding time in each of 40 time zones. Day of week band – Find the day of the week in any region by using Calendar – More than just a calendar, this band along with the map’s this feature allows you to determine international date line. -

INTERNATIONAL CENTRE for L L \ / ! / THEORETICAL PHYSICS

IC/88/215 ( i ^ INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR ll\ /!/ THEORETICAL PHYSICS / / GENERALIZATION OF THE TEST THEORY OF RELATIVITY TO NONINERTIAL FRAMES G.H. Abolghasem M.R.H. Khajehpour INTERNATIONAL and ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY R. Mansouri UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION IC/88/215 1. INTRODUCTION International Atomic Energy Agency In the theory of relativity, one usually synchronises the clocks by the so-called and Einstein's procedure using light signals. An alternative procedure, which has also been, United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation widely discussed, is the synchronisation by "slow transport* of clocks. The equivalence INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR THEORETICAL PHYSICS of the two procedures in inertial frames was first shown by Eddington (1963). In non- inertial frames the problem is a bit more subtle and it has recently been the subject of several articles with conflicting results. Cohen et al. (1983) have claimed that the two synchronisation methods are not equivalent, while Ashby and Allan (1984) have made a careful analysis of the problem and have established the equivalence of the two procedures. GENERALIZATION OF THE TEST THEORY To realise the practical importance of this problem, one needs only to consider the degree of OP RELATIVITY TO NONINERTIAL FRAMES * accuracy in time and frequency measurements obtained in the last two decades (lO~*»ec). (See Ashby and Allan (1984) and Allan (1983)). G.H. Abolghasero In this paper we approach the problem in the framework of the test theory of Department of Physics, Sharif University of Technology, Tehran, Iran special relativity suggested by Mansouri and Sexl (1077) (see also Mansouri (1988)). -

Partial List of Silent Auction Items Bidding Will Be Held in the School Gymnasium Saturday from 6:00 – 9:00 P.M., and Sunday from 9:00 A.M

Partial List of Silent Auction Items Bidding will be held in the school gymnasium Saturday from 6:00 – 9:00 p.m., and Sunday from 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. • "A Splash of Fall " Wreath • "Vintage" Fall Basket • "All About Christmas" Basket • "Winter Wayside" Framed Artwork • "Beach Front Villa" Artwork • "Wisconsin Finest" Photo • "Best Friends" Statue & Wash Your Hands • 1935 Mack Type 75BX Toy Firetruck Plaque • 1977 Ducks Unltd Jim Beam Decanter • "Bless This House" Wall Art • 1982 Ducks Unltd Whiskey Decanter • "Blessed Are They" Basket • 20" Boys Ambush Bike • "Broil', "Bake" & "Roast" Pan • A Trio of Wooden Frames • "Brothers" Watercolor Print • Aaron Rodgers Photo • "Christmas Delight" Wreath • Advanced Hair Design $25 Gift Certificate • "Crate & Barrel Baking Set" • Agritec Model Agricola Tractor • "Eiffel Tower" Wine or Towel Holder • All You Need For School Book Bag • "Hocus Pocus" Picture • American Girl Doll "Josephina" • "I Hate to Cook" Basket • American Girl Doll "Skylar" • "Lanie Holland" American Girl Doll • Ann's Coffee Cake • "Men's" Basket • Antique Marx Tin Doll House • "Old World Clock" • Antique Sled • "Opportunity" Framed Poster • Antique Wheelbarrow , • "Perfect Angel" Picture • Area Restaurants Gift Certificates • "Phyllis" Prestige Doll • Around the World Beer Basket • "Pieta" Statue • Autumn is Here Basket • "Rose" Collector Doll • Autumn Spectacle - Wood Ducks Picture • "Shauna" Porcelain Doll • Babysitting By Amanda • "Something For Everyone" Holiday Basket • Barbie's Basket • "Tea 4 - 2" Basket • Bedside Water -

7:00-8:30PM EST (World Clock) Title: Analyzing Street Crossings, Part 2

7:00-8:30PM EST (World Clock) Title: Analyzing Street Crossings, Part 2 Facilitator: Dona Sauerburger, Certified Orientation and Mobility Specialist, United States Presenters: Dr. Gene Bourquin, Orientation and Mobility Specialist Vickie Anderson, Client Services (Metro) Team Leader, O&M Specialist, Guide Dogs Queensland [Type text] Description: This is Part 2 of this two part presentation. Join a panel of hosts as we analyze intersections from all over the world! After a short introduction to standard street-crossing strategies, we will discuss as a group how effective those strategies would be at each intersection with its unique challenges, and how students could reduce the risks of crossing there. This part of the two part series will focus on signalized intersections from the following locations: • Thailand • Australia Table of Contents Dona Sauerburger, United States – Part 2 ............................................. 1 Dr. Gene Bourquin, Orientation and Mobility Specialist – Thailand ...... 20 DEFINITIONS ....................................................................................... 33 Overview of Robinson Rd West (minor road) and ................................ 35 Gympie Rd (major road) in Aspley, QLD .............................................. 35 Straight from the Traffic Engineer ......................................................... 37 Gympie & Robinson Signal Operations ................................................ 40 RISK ANALYSIS for Situations of Uncertainty ...................................... 44 -

Relativistic Rotation: a Comparison of Theories

Relativistic Rotation: A Comparison of Theories by Robert D. Klauber 1100 University Manor Dr., 38B Fairfield, Iowa 52556 rklauber[AT]iowatelecom.net or rklauber[AT]netscape.net Alternative theories of relativistic rotation considered viable as of 2004 are compared in the light of experiments reported in 2005. En route, the contentious issue of simultaneity choice in rotation is resolved by showing that only one simultaneity choice, the one possessing continuous time, gives rise, via the general relativistic equation of motion, to the correct Newtonian limit Coriolis acceleration. In addition, the widely dispersed argument purporting Lorentz contraction in rotation and the concomitant curved surface of a rotating disk is analyzed and argued to be lacking for more than one reason. It is posited that not by theoretical arguments, but only via experiment can we know whether such effect exists in rotation or not. The Coriolis/simultaneity correlation, and the results of the 2005 experiments, support the Selleri theory as being closest to the truth, though it is incomplete in a more general applicability sense, because it does not provide a global metric. Two alternatives, a modified Klauber ap- proach and a Selleri-Klauber hybrid, are presented which are consistent with recent experiment and have a global metric, thereby making them applicable to rotation problems of all types. Keywords: Relativistic; rotation; rotating frame; Sagnac; time discontinuity arXiv:gr-qc/0604118v2 16 Dec 2006 1 Introduction The recent book Relativity in Rotating Frames[1], edited by Rizzi and Ruggiero, acknowledged the little recognized lack of a universally accepted theory of relativistic rotation and presented several different theories by various invited contributors. -

Arxiv:Gr-Qc/0002017 V3 24 Feb 2000 \\ Obtained

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CERN Document Server \\ Title : Acceleration and Special Relativity. Author:Erez M.Yahalomi. Comments: html errors corrected, .gif files for equations and figures were added, a paragraph of an experimental evidence added ,correction of typing errors in eq 8, 3 fig, 18 pages Report-no :Bar Ilan University BIU-00-01 Subj-class:general relativity \\ The integration of acceleration over time before reaching the uniform velocity turns out to be the source of all the special relativity effects. It explains physical phenomena like clocks comparisons. The equations for space-time, mass and energy are presented. This phenomenon complements the explanation for the twins paradox. A Universal reference frame is obtained. \\ arXiv:gr-qc/0002017 v3 24 Feb 2000 2 ACCELERATION AND SPECIAL RELATIVITY E.M. Yahalomi Department of Physics, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat-Gam 52900, ISRAEL ABSTRACT The integration of acceleration over time before reaching the uniform velocity turns out to be the source of all the special relativity effects. It explains physical phenomena like clocks comparisons. The equations for space-time, mass and energy are presented. This phenomenon complements the explanation for the twins' paradox. A Universal inertial frame is obtained. *E mail : [email protected] 3 I. INTRODUCTION The basic equations of the special relativity concern time measurement in different moving frames. Assume the velocity of a moving frame is v, t is the time in the inertial frame and t' is the time in the moving reference frame,c is the velocity of light.The coordinates in the inertial and the reference frame are x and x' respectively. -

World Clock V1.0

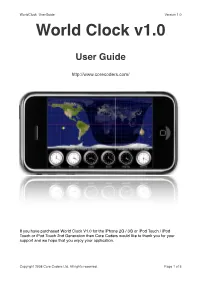

WorldClock_UserGuide Version 1.0 World Clock v1.0 User Guide http://www.corecoders.com/ If you have purchased World Clock V1.0 for the iPhone 2G / 3G or iPod Touch / iPod Touch or iPod Touch 2nd Generation then Core Coders would like to thank you for your support and we hope that you enjoy your application. Copyright 2008 Core Coders Ltd, All rights reserved. Page 1 of 5 WorldClock_UserGuide Version 1.0 Introduction The World Clock application displays the Earth and the position of the sun and where daylight and night are. As the seasons progress you will see the ever changing patterns of the Day Night display as the Earth orbits the Sun. The World Clock application has the following features: ★ 6 Independent clocks showing different times at different cities. ★ Clocks change colour depending on time. ★ Sun position display. ★ Equator display. ★ Latitude / Longitude Grid (15°) ★ Date display. ★ 1400+ City Database. ★ Landscape/Portrait animated changes. ★ Sort clocks in order or longitude. In addition the World Clock has the following addition features: ★ Low Power Mode (When screen is off) Diagram above gives a quick overview of the display, the clocks are updated every second and the Earth Day Night display is animated every minute. All animations are turned off when the phone is in standby mode so you will not notice any change in battery performance while leaving World Clock running. Copyright 2008 Core Coders Ltd, All rights reserved. Page 2 of 5 WorldClock_UserGuide Version 1.0 Change a City When the World Clock is initialised it comes with the following Cities pre-setup: Los Angeles, New York City, London, Moscow, Hong Kong, Melbourne Included within World Clock application is a database of cities (currently 1400+), that you can select by touching the specific clock you wish to change when in portrait mode.