Sound Synthesis, Representation and Narrative Cinema in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DSCH Journal No. 24

DOCUMENTARY III VARIANT AND VARIATION[1] IN THE SECOND MOVEMENT OF THE ELEVENTH SYMPHONY Lyudmila German The Eleventh Symphony, form, as it ‘resists’ develop- named Year 1905, is a pro- mental motif-work and frag- ach of Shostakovich’s gram work that relates the mentation. [2]” symphonies is unique in bloody events of the ninth of Eterms of design and January, 1905, when a large Indeed, if we look at the sec- structure. Despite the stifled number of workers carrying ond movement of the sym- atmosphere of censorship petitions to the Tsar were shot phony, for instance, we shall which imposed great con- and killed by the police in the see that its formal structure is strains, Shostakovich found Palace Square of St. Peters- entirely dependent on the nar- creative freedom in the inner burg. In order to symbolize rative and follows the unfold- workings of composition. the event Shostakovich chose ing of song quotations, their Choosing a classical form such a number of songs associated derivatives, and the original as symphony did not stultify with protest and revolution. material. This leads the com- the composer’s creativity, but The song quotations, together poser to a formal design that rather the opposite – it freed with the composer’s original is open-ended. There is no his imagination in regard to material, are fused into an final chord and the next form and dramaturgy within organic whole in a highly movement begins attacca. the strict formal shape of a individual manner. Some of The formal plan of the move- standard genre. -

The Creative Process

The Creative Process THE SEARCH FOR AN AUDIO-VISUAL LANGUAGE AND STRUCTURE SECOND EDITION by John Howard Lawson Preface by Jay Leyda dol HILL AND WANG • NEW YORK www.johnhowardlawson.com Copyright © 1964, 1967 by John Howard Lawson All rights reserved Library of Congress catalog card number: 67-26852 Manufactured in the United States of America First edition September 1964 Second edition November 1967 www.johnhowardlawson.com To the Association of Film Makers of the U.S.S.R. and all its members, whose proud traditions and present achievements have been an inspiration in the preparation of this book www.johnhowardlawson.com Preface The masters of cinema moved at a leisurely pace, enjoyed giving generalized instruction, and loved to abandon themselves to reminis cence. They made it clear that they possessed certain magical secrets of their profession, but they mentioned them evasively. Now and then they made lofty artistic pronouncements, but they showed a more sincere interest in anecdotes about scenarios that were written on a cuff during a gay supper.... This might well be a description of Hollywood during any period of its cultivated silence on the matter of film-making. Actually, it is Leningrad in 1924, described by Grigori Kozintsev in his memoirs.1 It is so seldom that we are allowed to study the disclosures of a Hollywood film-maker about his medium that I cannot recall the last instance that preceded John Howard Lawson's book. There is no dearth of books about Hollywood, but when did any other book come from there that takes such articulate pride in the art that is-or was-made there? I have never understood exactly why the makers of American films felt it necessary to hide their methods and aims under blankets of coyness and anecdotes, the one as impenetrable as the other. -

The Film Music of Edmund Meisel (1894–1930)

The Film Music of Edmund Meisel (1894–1930) FIONA FORD, MA Thesis submitted to The University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy DECEMBER 2011 Abstract This thesis discusses the film scores of Edmund Meisel (1894–1930), composed in Berlin and London during the period 1926–1930. In the main, these scores were written for feature-length films, some for live performance with silent films and some recorded for post-synchronized sound films. The genesis and contemporaneous reception of each score is discussed within a broadly chronological framework. Meisel‘s scores are evaluated largely outside their normal left-wing proletarian and avant-garde backgrounds, drawing comparisons instead with narrative scoring techniques found in mainstream commercial practices in Hollywood during the early sound era. The narrative scoring techniques in Meisel‘s scores are demonstrated through analyses of his extant scores and soundtracks, in conjunction with a review of surviving documentation and modern reconstructions where available. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) for funding my research, including a trip to the Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt. The Department of Music at The University of Nottingham also generously agreed to fund a further trip to the Deutsche Kinemathek, Berlin, and purchased several books for the Denis Arnold Music Library on my behalf. The goodwill of librarians and archivists has been crucial to this project and I would like to thank the staff at the following institutions: The University of Nottingham (Hallward and Denis Arnold libraries); the Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt; the Deutsche Kinemathek, Berlin; the BFI Library and Special Collections; and the Music Librarian of the Het Brabants Orkest, Eindhoven. -

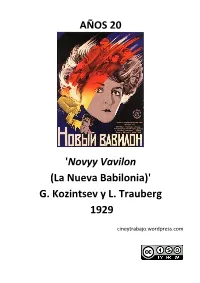

Novyy Vavilon (La Nueva Babilonia)' G

AÑOS 20 'Novyy Vavilon (La Nueva Babilonia)' G. Kozintsev y L. Trauberg 1929 cineytrabajo.wordpress.com Título original: Новый Вавилон/Novyy Vavilon; URSS, 1929; Productora: Sovkino; Director: Grigori Kozintsev y Leonid Trauberg. Fotografía: Andrei Moskvin (Blanco y negro); Guión: Grigori Kozintsev y Leonid Trauberg; Reparto: David Gutman, Yelena Kuzmina, Andrei Kostrichkin, Sofiya Magarill, A. Arnold, Sergei Gerasimov, Yevgeni Chervyakov, Pyotr Sobolevsky, Yanina Zhejmo, Oleg Zhakov, Vsevolod Pudovkin; Duración: 120′ “*...+¡La Comuna, exclaman, pretende abolir la propiedad, base de toda civilización! Sí, caballeros, la Comuna pretendía abolir esa propiedad de clase que convierte el trabajo de muchos en la riqueza de unos pocos. La Comuna aspiraba a la expropiación de los expropiadores.*...+” ¹ (Karl Marx) Sinopsis Ambientada en el París de 1870-1871, ‘La nueva Babilonia’ nos cuenta la historia de la instauración de la Comuna de París por parte de un grupo de hombres y mujeres que no quieren aceptar la capitulación del Gobierno de París ante Prusia en el marco de la guerra franco-prusiana. Louise, dependienta de los almacenes “La nueva Babilonia”, va a ser una de las más apasionadas defensoras de la Comuna hasta su derrocamiento en mayo de 1871. Comentario En 1929, Grigori Kozintsev y Leonid Trauberg, dos de los creadores y difusores de la Fábrica del Actor Excéntrico (FEKS), escribieron y dirigieron la que se considera su obra conjunta de madurez: ‘Novyy Vavilon (La nueva Babilonia)’. Como muchas otras obras soviéticas se sirven de un hecho histórico real para exaltar la Revolución, pero la peculiaridad de la película de Trauberg y Kozintsev reside en que no sólo se remontan muchos años atrás en el tiempo, sino que además cambian de ubicación, situando la acción en la época de la guerra franco-prusiana de 1870 y la instauración de la Comuna de París al año siguiente. -

Doi “Is Whispering Nothing?”: Anti-Totalitarian Implications in Grigori K

DOI https://doi.org/10.36059/978-966-397-199-5/126-158 “IS WHISPERING NOTHING?”: ANTI-TOTALITARIAN IMPLICATIONS IN GRIGORI KOZINTSEV’S HAMLET Nataliya M. Torkut Introduction In May 2016, Cultura.ru, a popular internet portal, released a video-lecture dedicated to the film adaptation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet directed by Grigori Kozintsev (1964)1. This 20-minute video is aimed at introducing the contemporary Russian teen audience to this masterpiece of the Soviet cinema. The lecturers are Sasha Frank, a renowned contemporary filmmaker, and professor Boris Lyubimov, an authoritative Russian theatrical expert. As an integral part of an ambitious project One Hundred Lectures. The History of Native Cinema, specifically designed for school students, this video lecture popularizes both, the most famous Shakespeare’s tragedy and its successful screen version made by the prominent Soviet film-maker. The lecturers see Grigori Kozintsev’s Hamlet as a powerful instrument of stimulating the young generation’s interest in Shakespeare. Appealing to the cinema in the process of teaching literature has become a popular strategy within the contemporary educational paradigm. As M. T. Burnet points out in his monograph with a self-explanatory title Filming Shakespeare in Global Marketplace, “Shakespeare films are widely taught in schools, colleges, and universities; indeed, they are increasingly the first port of call for a student encounter with the Bard2. R. Gibson offers convincing arguments about the effectiveness of using the so-called ‘active, critical viewing’ of films and videos in teaching Shakespeare. The scholar also outlines the purposes of this approach which “involves close study of particular scenes, actions or speeches”: “Student inquiry should focus on how a Shakespeare film has been constructed, how its meanings have been made, and whose interests are served by those meanings. -

National Gallery of Art Fall 2012 Film Program

FILM FALL 2012 National Gallery of Art 9 Art Films and Events 16 A Sense of Place: František Vláčil 19 Shostakovich and the Cinema 22 Chris Marker: A Tribute 23 From Tinguely to Pipilotti Rist — Swiss Artists on Film 27 Werner Schroeter in Italy 29 American Originals Now: James Benning 31 On Pier Paolo Pasolini 33 Marcel Carné Revived Journey to Italy p. 9 National Gallery of Art cover: Marina Abramović: The Artist Is Present p. 11 Films are screened in the Gallery’s East Building Audito- This autumn’s offerings celebrate work by cinematic rium, Fourth Street and Pennsylvania Avenue NW. Works pioneers, innovators, and master filmmakers. The ciné- are presented in original formats and seating is on a concert Alice Guy Blaché, Transatlantic Sites of Cinéma first-come, first-seated basis. Doors open thirty minutes Nouveau features films by this groundbreaking direc- before each show and programs are subject to change. tor, accompanied by new musical scores, presented in For more information, visit www.nga.gov/programs/film, association with a University of Maryland symposium. e-mail [email protected], or call (202) 842-6799. Other rare screenings include three titles from the 1960s by Czech filmmaker František Vláčil; feature films made in Italy by German Werner Schroeter; two programs of work by the late French film essayist Chris Marker; an illustrated lecture about, a feature by, and a portrait of Italian auteur Pier Paolo Pasolini; a series devoted to the film scores of composer Dmitri Shostakovich; highlights from the 2012 International Festival of Films on Art; and recent docu- mentaries on a number of Switzerland’s notable contem- porary artists. -

Associate Professor in Art and Music Honors Adviser

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE SCHOOL OF MUSIC HEARING VOICES IN SHOSTAKOVICH UNCOVERING HIDDEN MEANINGS IN THE FILM ODNA CAROLE CHRISTIANA SMITH Spring 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Music with honors in Music Reviewed and approved* by the following: Eric J. McKee Associate Professor of Music Thesis Supervisor Charles D. Youmans Associate Professor of Music Thesis Supervisor Mark E. Ballora Associate Professor in Art and Music Honors Adviser *Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. ABSTRACT While the concert works of Dmitri Shostakovich have been subject to much research and analysis by scholars, his works for film remain largely unknown and unappreciated. Unfortunately so, since Shostakovich was involved with many of the projects that are hallmarks of Soviet Cinema or that changed the course of the country‘s cinematic development. One such project, the film Odna (1931), was among the first sound films produced in the Soviet Union and exhibits the innovative methods of combining sound and image in order enhance to audience‘s understanding of the films message. This thesis will examine the use and representation of the human voice in the sound track of Odna and how its interaction with the visual track produces deeper levels of meaning. In designing the sound track, Shostakovich employs the voice in several contexts: recorded dialogue, songs, and vocal ―representations‖ whereby music mimics speech. These vocal elements will be examined through theoretical analysis in the case of music, and dramatic importance in the case of dialogue and sound effects. -

Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 an International Refereed/Peer-Reviewed English E-Journal Impact Factor: 3.019(IIJIF)

www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed/Peer-reviewed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 3.019(IIJIF) Shakespeare under the Soviet Bloc Oumeima Mouelhi Assistant Professor/ PhD holder in English Literature The High Institute of Human Sciences of Tunis Tunisia Abstract Under the Eastern European theatre, a number of allusions and inferences endeavored to raise the curtain of silence over the true character of totalitarian society. Situating Shakespeare within the ideological and cultural debates and conflicts of Eastern Europe, Shakespeare‟s plays were a politically subversive tool mirroring the absolutism of the state and the anxiety of the people namely in East Germany and the Soviet Bloc. Sometimes appropriating his works freely for the purpose, the new productions of Shakespeare were fraught with all kinds of contemporary allusions to political events subtly criticizing the political system, just to add a facet of “political Shakespeare”. This paper seeks to explore the appropriation of Shakespeare‟s play, Macbeth, in Ukraine in an avan-gardist production by Les Kurbas, a play that has proved, uncommonly, responsive to the circumstances of a torn country. Les Kurbas‟s appropriation was appropriated to reflect the political turmoil and the general unease hovering over the country during the obscure days of the Second World War. Key Words: Shakespeare, Eastern Europe, Soviet Bloc, appropriation, Les Kurbas‟s Macbeth. Vol. 4, Issue 3 (October 2018) Dr. Siddhartha Sharma Page 58 Editor-in-Chief www.TLHjournal.com Literary Herald ISSN: 2454-3365 An International Refereed/Peer-reviewed English e-Journal Impact Factor: 3.019(IIJIF) Shakespeare has been appropriated to the ever-changing circumstances finding an echo in almost every sphere of the world thanks to the very elasticity of his plays and their ability to adapt to various situations. -

Postclassical Ensemble Presents D.C. Area Premiere of Dmitri Shostakovich’S Score to Silent Film, the New Babylon

PostClassical Ensemble presents D.C. area premiere of Dmitri Shostakovich’s score to silent film, The New Babylon Conductor Angel Gil-Ordóñez leads PostClassical Ensemble as they perform Shostakovich’s first film score live to a screening at AFI Silver on March 30th and 31st, 2018 Washington, D.C. (March XX, 2017) – An astonishing achievement from the peak of the Soviet silent film era, The New Babylon was the first of composer Dimitri Shostakovich’s historic collaborations with filmmaker Grigori Kozintsev. PostClassical Ensemble, conducted by Angel Gil-Ordóñez, presents the D.C. area premiere of Shostakovich’s score, performing live to a screening of the 1929 film at AFI Silver Theatre and Cultural Center on Friday, March 30, 2018 at 8:30 p.m. and Saturday, March 31, 2018 at 2 p.m. Runtime of the film is 93 minutes. Tickets and information are available at www.postclassical.com. Both whimsical and tragic, The New Babylon is set during the Paris Commune, a socialist revolutionary government that ruled Paris for a short period in 1871. The film is centered around the forbidden romance between a department store shopgirl (Elena Kuzmina) and a young soldier (Pyotr Sobolevsky) who find themselves on opposing sides of the political turmoil. Originally banned for its excess and aesthetic frivolity, this energetic avant-garde extravaganza represents the apex of the experimental Factory of the Eccentric Actor (FEKS), founded by directors Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg, and was to be their final silent film. New Yorker music critic Alex Ross wrote of The New Babylon: “Kozintsev, together with Leonid Trauberg, aped the madcap pacing of the circus, the variety theater, and American movies, and Shostakovich followed suit.” The New Babylon was the beginning of a fruitful collaborative partnership between Shostakovich and the filmmaker Kozintsev, which continued through their epochal King Lear (1971). -

Download Booklet

572824-25 bk Babylon_572824-25 bk Babylon 28/08/2011 11:37 Page 20 www.chostakovitch.org Reproduced with the kind permission of Irina Antonovna Shostakovich 8.572824-25 20 572824-25 bk Babylon_572824-25 bk Babylon 28/08/2011 11:37 Page 2 Dmitry Shostakovich (1906-1975) Mark Fitz-Gerald Music for the film Mark Fitz-Gerald studied in London at the Royal College of Music, where his professors included NorMan Del Mar, winning all the Major prizes for both orchestral and operatic conducting. It was New Babylon (1929) during this tiMe that Henze invited hiM to take part in the first Cantiere Internazionale d!Arte in Montepulciano, as a result of CD 1 43:15 CD 2 48:08 which he was invited regularly to Switzerland as Guest Conductor of the basel sinfonietta. FroM 1983 to 1987 he was Artistic Director 1 Reel 1: 1 Reel 5: of the RIAS Jugendorchester (West Berlin) where his innovative General Sale. Versailles against Paris. FilMharMonic Concerts received Much acclaiM and were later !War – Death to the Prussians" 9:02 !Paris has stood for centuries" 10:21 Made available on CD. He returned there to continue the series with the Berlin Rundfunkorchester in 1992. Since then he has perforMed 2 Reel 2: 2 Reel 6: The Barricade. the very specialised task of accoMpanying silent filMs live with Head over Heels. !Paris" 10:01 !The 49th day of defence" 14:51 orchestra, with Much success in Many countries and festivals throughout the world. Described as “one of the indispensable 3 Reel 3: 3 Reel 7: To the Firing Squad. -

Jwsphamlet Copy

Klassiki Cinema on the Hop Tuesday 21 April 2020 Hamlet (1964) #Klassiki3 Directed by Grigori Kozintsev Shakespeare’s Hamlet is a tragedy perceived by many to be translation, which imbued Shakespeare with the beauty and about internality, inaction and inertia. Any yet, Grigori specificity of the Russian language. There were many letters Kozintsev’s adaptation is an active affair, zipping along at a exchanged between Kozintsev and Pasternak, as the director brief two hours and twenty minutes. The film boasts a castle used Pasternak’s insight as a translator to understand how to setting that could hold its own against contemporary adapt and reduce the screenplay. Moreover Shostakovich, a blockbusters, the Baltic shore as an elemental backdrop and a long time collaborator with Kozintsev, developed the score. dazzling Shostakovich score. These elements, which are largely The pieces Shostakovich wrote for the film (reworking a score inaccessible to a theatre production, juxtapose Hamlet’s he produced for a 1920s theatre production) range from interiority and illuminate what Kozintsev saw as the themes for characters, grand orchestral movements and quiet production’s major tension. He was determined to, ‘Not adapt moments of diagetic sound. Without doubt the stature of Shakespeare to the cinema, but the cinema to Shakespeare’, Kozinstev’s Hamlet, is due to the collaboration of three Russian thereby succeeding in making one of the great if not the Cultural greats, with Kozintsev marrying their insights and greatest film adaptations of Shakespeare in any language. contributions to make one perfect whole. The unique visual language of the film is beautiful, gothic and The shots in Kozintsev’s Hamlet demonstrate the play’s dark. -

The Shakespeare Films of Grigori Kozintsev

The Shakespeare Films of Grigori Kozintsev The Shakespeare Films of Grigori Kozintsev By Michael Thomas Hudgens The Shakespeare Films of Grigori Kozintsev By Michael Thomas Hudgens This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Michael Thomas Hudgens All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0317-8 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0317-5 For my grandchildren Come not between the dragon and his wrath. —Lear There could be no golden mean. —Kozintsev TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................................ ix Part I: King Lear Chapter One ................................................................................................. 3 ‘Make it new’ Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 25 Dramatis Personae Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 51 In the Eye of the Storm Chapter Four .............................................................................................. 63 A World Turned Topsy-turvy