Writing in the Key of Life: Inquiry Into Writing Processes and Pedagogies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FHSST Physics

The Free High School Science Texts: A Textbook for High School Students Studying Physics. FHSST Authors1 August 5, 2005 1See http://savannah.nongnu.org/projects/fhsst Copyright c 2003 \Free High School Science Texts" Permissionis granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front- Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled \GNU Free Documentation License". i Contents I Physics 1 1 Units 3 1.1 PGCE Comments . 3 1.2 `TO DO' LIST . 3 1.3 Introduction . 3 1.4 Unit Systems . 4 1.4.1 SI Units (Systeme International d'Unit¶es) . 4 1.4.2 The Other Systems of Units . 5 1.5 The Importance of Units . 6 1.6 Choice of Units . 7 1.7 How to Change Units| the \Multiply by 1" Technique . 7 1.8 How Units Can Help You . 8 1.8.1 What is a `sanity test'? . 8 1.9 Temperature . 8 1.10 Scienti¯c Notation, Signi¯cant Figures and Rounding . 9 1.11 Conclusion . 10 2 Waves and Wavelike Motion 11 2.1 What are waves? . 11 2.1.1 Characteristics of Waves : Amplitude . 11 2.1.2 Characteristics of Waves : Wavelength . 12 2.1.3 Characteristics of Waves : Period . 12 2.1.4 Characteristics of Waves : Frequency . 13 2.1.5 Characteristics of Waves : Speed . 13 2.2 Two Types of Waves . -

Perkins Institution

SEVENTY-THIRD ANNUAL REPORT THE TRUSTEES Perkins Institution Massachusetts School for the Blind, FOR THE YEAR ENDING August 31, 1904. BOSTON Press of Geo. H. Ellis Co., 272 Congress Street 1905 CommontDealti^ of QpasJjsaci^ujsett^, Perkins Institution and Massachusetts School for the Bund, South Boston, October 17, 1904. To the Hon. Wm. M. Olin, Secretary of State, Boston. Dear Sir: — I have the honor to transmit to you, for the use of the legislature, a copy of the seventy-third annual report of the trustees of this institution to the corporation thereof, together with that of the treasurer and the usual accompanying documents. Respectfully, MICHAEL ANAGNOS, Secretary. OFFICERS OF THE CORPORATION I 904- I 905. FRANCIS H. APPLETON, President. AMORY A. LAWRENCE, Vice-President. WILLIAM ENDICOTT, Jr., Treasurer. MICHAEL ANAGNOS, Secretary. BOARD OF TRUSTEES. FRANCIS H. APPLETON. J. THEODORE HEARD, M.D. WM. LEONARD BENEDICT. EDWARD JACKSON. WILLIAM ENDICOTT. GEORGE H. RICHARDS. Rev. PAUL REVERE FROTHINGHAM. WILLIAM L. RICHARDSON, M.D. CHARLES P. GARDINER. RICHARD M. SALTONSTALL. N. P. HALLOWELL. S. LOTHROP THORNDIKE, Chairman. STANDING COMMITTEES. Monthly Visiting Committee, whose duty it is to visit and inspect the Institution at least once in each month. 1905. 1905. January, . Francis H. Appleton. July, ... J. Theodore Heard. February, . Wm. L. Benedict. .\ugust, . Edward Jackson. March, . William Endicott. September. George H. Richards. April, . Paul R. Froth incham October, . William L. Richardson. May, . Charles P. Gardiner. November, . Richard M. Saltonstall. June, . N. P. Hallowell. December, . S. Lothrop Thorndike. Committee on Education. House Committee. George H. Richards. William L. Richardson, M.D. Rev. Paul Revere Frothingham. -

Wade Park Pharmacy

Mi JS mSSSESkL EMXfix: PMHCT^ ^ Foreword n^HIS, our Silver Jubilee Annual, displays the earnest efforts of the editors to record the progress of an other eventful year in the history of our Alma Mater. We have devoted part of this volume to the achieve ments of those who have been graduated from East dur ing the twenty-five years of her existence. We hope that in the future our efforts may help to recall many pleasant memories of the years spent here. In presenting the Jubilee Annual we ask only your consideration for our shortcomings. ^ J* <* <* <* The Editors If" T."" "•jfM»'>««'—*«t^jnit(n»'*iin*tu """M*ur|||l*"<*iir||JJ|Iinj||i||l"'u ,T"',n||IJlrJ|••*-•»»»»JJl^»^'*•"filf|r|r^JrrJ(*»",J•»«rt/rj|lJr»^1lll^•»*,,"*""J*^(^,,1 """«i'ii'»,i.""'qiii"»"""H/ti'1' ''iiiiii«''''»'","i«i'i|||| 1 |N),,:::•;..... \\./(-'Vi ^ \i "j,"-':: i,'- ,.y^..tfy& 73y} --•' i""" (""'• ':.'•"•.. jjUllllliilitiilUiiiii Illi.< ln.nMilli,,,! i, mlllllllu,,, ,iilllllllllllin»..,.„„n„lli.„,iih»illliii*lli ...nllk.M.ilIiiii/Nliilllliilllmi,.. .*<">"' ) ( r1' \ 'X,0* K. \ iEaat l|tgtj ilubilee Annual "!A \ ) :"/ > > (ttonttnta w['rtA« Dedication 5 Annual Board 8 V.iiihiiniiiHii,,,^ Faculty 10 ''ifiili '"M! "'l""H I'llllS Seniors 19 ill" I Graduates 47 ••..' III"" 3 I i'| 12B Class 58 lllNllll Juniors 71 11/ l'-v, 10A Class 83 I 10B Class 86 'wN., Clubs , 89 Student Council 121 \ v.. Blue and Gold 127 Military Training 129 11 iiH I'll! ""i Debating 133 Music 137 Athletics 149 '>i The Story Teller 161 p:u Dramatics 179 Alumni 187 wi •••';' Jokes 201 v ' l ''' Calendar 211 v p v V. -

1991 Collegian

it*. , . J ‘ *"■ Ky.' ' 'w^w»SE:r. *:m8§§i ^feJlPP PMMMS IK* ,;U . -.V'* ■■ :. mm fmgmm >- * . * ' aBeSflft ‘%v’ i . iinHP? 'w* Up (f|is sJSfikii'Sf'i J*^®**^ | «>. >i CP 4 ‘ ' 'f'-:irW'y 'i > '-tv * '' -* «**«*#•’*■ .-■'*■*'*! wfcWwjf *•> • ,4t, *' . •** mm P ■ V-a.f’,' ? && MlililNHHHHBiSilHH m iCffiiBiHiiil EDITORIAL With aspirations to become the next Nancy Wake, Phillip Adams and Miriam Borthwick the Collegian Committee began mm its gruelling task of producing this wondrous manuscript. At the beginning our naiviety led us to believe that reports miraculously land in the ‘in’ file, photos are taken by themselves and the final magazine arrives in all its splendour out of thin air. After two weeks, this illusory belief was shattered, thanks to Mrs. Shepherd’s constant reminders and imposed deadlines, the Collegian Committee set about performing its actual task. People owning reports were hounded and harassed (by the secret Collegian Force) photography sessions were ruled with an iron fist and the school body was subjected to the revolutionary 'A-:-- torture, technique of Collegian Committee advertising (thanks Mrs. Pyett for the loan of your sunnies). Through these trials and tribulations the Collegian Committee has brought about several changes as you will no doubt notice. We hope that these alterations improve the overall effect of the 1991 Collegian. Finally as the year draws to an end, I would like to thank Mrs. Shepherd plus Mr. Thompson for their invaluable help and the entire Collegian Committee for their tireless work. I am sure that they’d all agree that working on the Collegian was a rewarding and enjoyable experience. -

Psaudio Copper

Issue 142 AUGUST 2ND, 2021 Is there a reader among us who doesn’t dig ZZ Top? We mourn the passing of Joseph Michael “Dusty” Hill (72), bassist, vocalist and keyboardist for the tres hombres. Blending blues, boogie, bone-crushing rock, born-for-MTV visuals, humor and outrageousness – they once took a passel of live animals on stage as part of their 1976 – 1977 Worldwide Texas Tour – Hill, drummer Frank Beard and guitarist Billy F. Gibbons have scorched stages worldwide. As a friend said, “it’s amazing how just three guys could make that much sound.” Rest in peace, Mr. Hill. In this issue: Anne E. Johnson gets inspired by the music of Renaissance composer William Byrd, and understands The Animals. Wayne Robins reviews Native Sons, the superb new album from Los Lobos. Ray Chelstowski interviews The Immediate Family, featuring studio legends Waddy Wachtel, Lee Sklar, Russ Kunkel and others, in an exclusive video interview. I offer up more confessions of a record collector. Tom Gibbs finds much to like in some new SACD discs. John Seetoo winds up his coverage of the Audio Engineering Society’s Spring 2021 AES show. Ken Sander travels through an alternate California reality. WL Woodward continues his series on troubadour Tom Waits. Russ Welton interviews cellist Jo Quail, who takes a unique approach to the instrument. In another article, he ponders what's needed for sustaining creativity. Adrian Wu looks at more of his favorite analog recordings. Cliff Chenfeld turns us on to some outstanding new music in his latest Be Here Now column. -

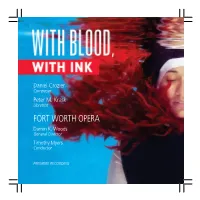

FORT WORTH OPERA Darren K

Daniel Crozier Composer Peter M. Krask Librettist FORT WORTH OPERA Darren K. Woods General Director Timothy Myers Conductor PREMIERE RECORDING WITH BLOOD, WITH INK Music...........................................Daniel Crozier Libretto.......................................Peter M. Krask Translations of poems of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz by Margaret Sayers Peden as published in Sor Juana, or The Traps of Faith by Octavio Paz, used by arrangement with Harvard University Press. Conductor...................................Timothy Myers Stage Director.......................... Dona D. Vaughn Producing Director.........................Kurt Howard Director of Production...............Adam Schwartz Scenic Designer................................Erhard Rom Costume Designer.......................Austin Scarlett Lighting Designer............................Sean Jeffries Makeup / Wig Designer..................Steven Bryant Stage Manager.............................Joe Gladstone Assistant Director.......................David Gutierrez Chorus Master.............................Stephen Carey CAST: Dying Juana..................................Sandra Lopez Young Juana..............................Vanessa Becerra María Luisa...............................Audrey Babcock Padre Antonio..................................Ian McEuen Archbishop Seijas...........................Jesse Enderle PROGRAM NOTES.............by Peter M. Krask Sor Isabel...................................Corrie Donovan “I spoke the truth. I spoke the truth but none Sor Rosa........................................Clara -

Artist 5Th Dimension, the 5Th Dimension, the a Flock of Seagulls

Artist 5th Dimension, The 5th Dimension, The A Flock of Seagulls AC/DC Ackerman, William Adam and the Ants Adam Ant Adam Ant Adam Ant Adams, Bryan Adams, Bryan Adams, Ryan & the Cardinals Aerosmith Aerosmith Alice in Chains Allman, Duane Amazing Rhythm Aces America America April Wine Arcadia Archies, The Asia Asleep at the Wheel Association, The Association, The Atlanta Rhythm Section Atlanta Rhythm Section Atlanta Rhythm Section Atlanta Rhythm Section Atlanta Rhythm Section Atlanta Rhythm Section Atlanta Rhythm Section Autry, Gene Axe Axton, Hoyt Axton, Hoyt !1 Bachman Turner Overdrive Bad Company Bad Company Bad Company Bad English Badlands Badlands Band, The Bare, Bobby Bay City Rollers Beach Boys, The Beach Boys, The Beach Boys, The Beach Boys, The Beach Boys, The Beach Boys, The Beatles, The Beatles, The Beatles, The Beatles, The Beaverteeth Bennett, Tony Benson, George Bent Left Big Audio Dynamite II Billy Squier Bishop, Elvin Bishop, Elvin Bishop, Stephen Black N Blue Black Sabbath Blind Faith Bloodrock Bloodrock Bloodrock Bloodstone Blue Nile, The Blue Oyster Cult !2 Blue Ridge Rangers Blues Brothers Blues Brothers Blues Brothers Blues Pills Blues Pills Bob Marley and the Wailers Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys BoDeans Bonham Bonoff, Karla Boston Boston Boston Boston Symphony Orchestra Bowie, David Braddock, Bobby Brickell, Edie & New Bohemians Briley, Martin Britny Fox Brown, Clarence Gatemouth Brown, Toni & Garthwaite, Terry Browne, Jackson Browne, Jackson Browne, Jackson Browne, Jackson Browne, Jackson Browne, Jackson Bruce -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Gifts of Divine Love Messages from Sathya Sai Baba to Bhagavan Sri

Gifts of Divine Love Messages from Sathya Sai Baba Received by Carol Riddell. Dedicated with Love and Reverence To Bhagavan Sri Sathya Sai Baba. I asked Bhagavan Baba to bless the text of this book for publication on the Darshan Line at Prasanthi Nilayam Ashram. He laid His hand on the typescript and said, "Yes, I'll Bless." All the messages were signed 'Sai Baba' when they were received. Copyright , Carol Riddell, 1998. All rights reserved. The Messages. Contents. Taking Part in Change. / My Grace is with You. / World Transformation. / The Great Adventure. Find the Highest Quality. / The Days of Transformation. / Who is Important? / A Parting of the Ways. The Source of Beauty. / I am always with You. / Turning on the Light. / I Am Love, I Am Bliss. My Way. / Easter Message - 1. / The Hymn of Praise. / Your Are Part of Me. The Energy of a New Humanity. / I Am Going to be Recognised Everywhere. / All Heaven Is Happy. / Playing in Harmony. Surrender to the Creator. / The Journey to Oneness. / Truth Hidden in Every Form. / The Door That Opens. / See the Large Picture of Yourselves. Love Brought You Here. / The Salt of the Earth. / At the Eye of the Storm. / Develop Vision. Let Me Take Responsibility. / Easter Message - 2. (Parts 1 - 4) / The Play of Life. / Nothing Is Local Anymore. Trust Your Inner Wealth. / Only the Inner Ground is Firm. (Parts 1 & 2) / I'm Here to Help! / Discover Continents in Yourselves. Each of You Is a Special Soul. (Parts 1 & 2) / Let Us Experience Re-union. / To Heal, You Must Be Healed. -

The Electric Light Orchestra ELO 2 Mp3, Flac

The Electric Light Orchestra E.L.O. 2 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: E.L.O. 2 Country: France Style: Symphonic Rock, Classic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1424 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1596 mb WMA version RAR size: 1232 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 553 Other Formats: AA WAV MIDI AAC ASF AU AIFF Tracklist Hide Credits 1 In Old England Town (Boogie No. 2) 6:52 2 Mama... 6:59 Roll Over Beethoven 3 7:02 Written-By – Chuck Berry 4 From The Sun To The World (Boogie No. 1) 8:17 5 Kuiama 11:14 Bonus Tracks: 6 Showdown 4:10 7 In Old England Town (Instrumental) 2:42 8 Baby I Apologise 3:42 Previously Unreleased: "The Elizabeth Lister Observatory Sessions" 9 "Auntie" (Ma-Ma-Ma Belle/Take 1) 1:19 10 "Auntie" (Ma-Ma-Ma Belle/Take 2) 4:03 11 "Mambo" (Dreaming Of 4000/Take 1) 5:01 12 Everyone's Born To Die 4:37 Roll Over Beethoven (Take 1) 13 8:16 Written-By – Chuck Berry Credits Bass, Vocals [Vocal Harmonies] – Michael D'Albuquerque Cello – Colin Walker , Mike Edwards Design [Cover Design] – Hipgnosis Engineer – John Middleton Liner Notes – 岩本晃市郎* Percussion – Bev Bevan Producer, Vocals, Guitar, Synthesizer [Moog], Harmonium – Jeff Lynne Synthesizer [Moog], Piano, Guitar, Harmonium, Vocals [Vocal Harmonies] – Richard Tandy Violin – Wilf Gibson Written-By – Jeff Lynne (tracks: 1, 2, 4 to 12) Notes ℗1973, 2003 EMI Records Ltd. Digitally remastered Comes in a CD sized papersleeve album replica (gatefold), with obi-strip, printed inner-sleeve and insert of notes mostly in Japanese. -

'Em All Together: African American Marxist Approaches to Colson

39 Lumpen ‘Em All Together: African American Marxist Approaches to Colson Whitehead’s John Henry Days By Tarrell R. Campbell Abstract: In Colson Whitehead’s John Henry Days, the psychological wounds of the novel’s pro- tagonist––J. Sutter––foreshadow the physical wounds that he will experience, ultimately resulting in his death. I examine Sutter’s abhorrence of the American South and locate such psychic scar- ring in the history of Black bodies in America. As a result of the hoped-for racial progress ushered in by the Brown decision, Sutter is represented as an exemplary member of the List. The List functions as a metaphor for the colorblind society suggested by Brown. In furthering the desires of those who control the List, Sutter must confront his fears associated with traveling from the North to the South. Geographical location signifies a sense of woundedness and a sense of loss in some African American Marxist literary traditions centered on generative uses of the lumpenproletariat and transience. I examine the costs of such migratory movement within and without the South in John Henry Days. For Sutter, the movement South from the North leads to death. I juxtapose Sut- ter’s transience and death with the lumpen literary schema espoused by Richard Wright, Margaret Walker, and Ralph Ellison. I argue that the the destruction of J. Sutter’s body signifies that the Dream––the myth––of African American full enfranchisement and integration into the fabric of American society remains deferred in many respects. Such an understanding may be instructive in these more recent times when the destruction of Black bodies is routinely disseminated on visual platforms to whet voyeuristic appetites of an American populace whose hunger is seemingly never satisfied. -

Eagles Bonus CD 1 CD 10 Desperado 1 CD 10 Eagles 1 CD 10 Greatest

Eagles Bonus CD 1 CD 10 Desperado 1 CD 10 Eagles 1 CD 10 Greatest hits volume 2 1 CD 31 Hotel California 1 CD 10 Live 2 CD 2 On the border 1 CD 10 One of these nights 1 CD 10 The complete greatest hits 2 CD 2 Their greatest hits 1 CD 31 The legend of 1 CD 18 The long run 1 CD 10 Unplugged (second night) 2 CD 162 Eakes, Bobbie & Jeff Trachta Bold and beautiful duets 1 CD 18 Earth & Fire 50 jaar Nederpop classic bands - 2008 1 CD 156 Andromeda girl - 1981 1 LP 175 Atlantis - 1973 1 LP 156 Diamond star collection 1 CD 69 Earth & fire 1 CD 52 + 69 Gate to infinity 1 LP 240 Originals 1 CD 69 Reality fills fantasy 1 CD 62 Song of the marching children - Atlantis - 1971 - 1973 1 CD 69 The singles 1 CD 69 To the world of the future 1 CD 164 Earth Wind & Fire All 'n all - 1999 1 CD 114 Avatar 1 CD 28 Dance trax - 1988 1 CD 41 Dutch collection 2 CD 98 Earth Wind & fire 1 CD 7 Electric universe 1 CD 7 Faces 1 CD 28 Gold - 1991 1 CD 125 Gratitude - 1975 1 LP 164 Heritage tour live at the Tokyo dome - 1990 1 CD 125 I am - 1979 1 LP 164 In concert 1 CD 28 In the name of love 1 CD 7 Last day and time 1 CD 7 Live by request - 1996 1 CD 125 Live in Atlanta - 1989 1 LP 125 Live in Budokan hall Tokyo - 1994 1 CD 125 Live in Florida - EWF & Chicago 1 CD 41 Live in Liverpool - 1975 1 LP 125 Live in Oakland coliseum - 1981 1 LP 125 Millennium 1 CD 16 Open our eyes 1 CD 7 Plugged in and live 1 CD 7 Spirit 1 CD 7 That's the way of the world 1 CD 7 The promise 1 CD 7 The very best - 1994 1 CD 70 Touch the world live in Spain - 1988 1 LP 125 Easton, Sheena Madness,