Economic Sociology in Israel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOI Number: 10.30520/Tjsosci.655840 SOCIO

Year:4, Volume:4, Number:7 / 2020 DOI Number: 10.30520/tjsosci.655840 SOCIO-ECONOMIC VARIABLES AND TAX COMPLIANCE IN THE SCOPE OF FISCAL SOCIOLOGY: A RESEARCH ON THE EUROPEAN UNION AND OECD* Rana DAYIOĞLU ERUL** ABSTRACT Fiscal sociology investigates financial events from a sociological point of view and explores the effects of tax and spending policies on society and also the role and influence of the elements that constitute society in defining these policies. As the tax system and policies of each country reflect the characteristics of the country's social, political, cultural and economic structure, tax systems differ according to the characteristics of the structure of the society. Tax systems that are in line with the social structure ensure that tax compliance is achieved at a high level. From this point of view, aim of the study is defined as investigating the level of interaction of the structural elements with tax compliance. In this respect, tax compliance and socio-economic variables that affect the structure of the society are included in the study and they are analyzed using panel data analysis covering the 2008-2016 time period by making comparisons between the European Union and OECD countries. As a result of the analysis, the main point in increasing tax compliance is that the tax policies are adopted by the society, for this reason it is concluded that implementations that reflect the society need to be taken as a basis while making the regulations on the tax system. Key Words: Fiscal sociology, tax compliance, panel data analysis, socio-economic variables. -

Redistribution & the New Fiscal Sociology: Race and The

Redistribution & the New Fiscal Sociology: Race and the Progressivity of State and Local Taxes Rourke O’Brien, Harvard University1 Abstract: States redistribute wealth through two mechanisms: spending and taxation. Yet, efforts to delineate the determinants of redistribution often focus exclusively on social spending. This article aims to explore how one important determinant of redistributive social spending—racial composition—influences preferences for and the structure of tax systems. First, using fixed- effects regression analyses and unique data on state and local tax systems, we demonstrate that changes in racial composition are associated with changes in the progressivity of state and local tax systems. Specifically, between 1995 and 2007, an increase in the percentage of Latinos in a state is associated with more regressive state and local tax systems as well as higher tax burdens on the poor. Second, using evidence from a nationally representative survey experiment, we find that individual preferences for taxation are actively shaped by the changing racial composition of the community. Finally, we show that in-group preference—or feeling “solidarity” with neighbors—is a key mechanism through which racial threat shapes preferences for taxation. By providing empirical evidence that racial composition drives preferences for taxation at the individual level as well as the structure of tax systems at the state and local levels, this paper serves as an important contribution to our understanding of welfare state policy and the determinants of redistribution as well as the broader project of the new fiscal sociology. 1 Direct all correspondence to Rourke O’Brien, Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies ([email protected]). -

The Classics in Economic Sociology

I The Classics in Economic Sociology There exists a rich and colorful tradition of economic sociology, which roughly began around the turn of the twentieth century and continues till today. This tradition has generated a number of helpful concepts and ideas as well as interesting research results, which this and the following chapter seek to briefly present and set in perspective. Economic soci- ology has peaked twice since its birth: in 1890–1920, with the founders of sociology (who were all interested in and wrote on the economy), and today, from the early 1980s and onward. (For the history of economic sociology, see Swedberg 1987, 1997; Gislain and Steiner 1995). A small number of important works in economic sociology—by economists as well as sociologists—was produced during the time between these two periods, from 1920 to the mid-1980s. The main thesis of this chapter, and of this book as a whole, is as follows: in order to produce a powerful economic sociology we have to combine the analysis of economic interests with an analysis of social relations. From this perspective, institutions can be understood as dis- tinct configurations of interests and social relations, which are typically of such importance that they are enforced by law. Many of the classic works in economic sociology, as I shall also try to show, hold a similar view of the need to use the concept of interest in analyzing the economy. Since my suggestion about the need to combine interests and social relations deviates from the existing paradigm in economic sociology, a few words will be said in the next section about the concept of interest as it has been used in social theory. -

Mind, Society, and Fiscal Sociology Richard E. Wagner Department Of

States and the Crafting of Souls: Mind, Society, and Fiscal Sociology Richard E. Wagner Department of Economics, 3G4 George Mason University Fairfax, VA 22030 USA [email protected] http://mason.gmu.edu/~rwagner Abstract For the most part, the theory of public finance follows economic theory in taking individual preferences as given. The resulting analytical agenda revolves around the ability of different fiscal institutions to reflect and aggregate those preferences into collective outcomes. This paper explores the possibility that to some extent fiscal institutions can influence and shape what are commonly referred to as preferences. Statecraft thus becomes necessarily a branch of soulcraft, in that the state is inescapably involved in shaping preferences through its impact on the moral imagination, and not just in reflecting or representing them. This paper first explores some general conceptual issues and then examines some particular illustrations. Keywords: endogenous preferences, fiscal institutions, constitutional economics, public enterprise States and the Crafting of Souls: Mind, Society, and Fiscal Sociology For the most part, the theory of public finance follows economic theory in taking individual preferences as given. The resulting analytical agenda revolves around the ability of different fiscal institutions to reflect and aggregate those preferences into collective outcomes. This paper explores the possibility that to some extent fiscal institutions, and the fiscal practice that those institutions generate, can influence and shape what are commonly referred to as preferences. In standard public finance, the activities of the state simply represent offerings by alternative vendors to those that exist in private markets. Hence, shoppers buy some things from public goods stores and other things from private goods stores. -

Taxes and Fiscal Sociology Isaac William Martin and Monica Prasad

Taxes and Fiscal Sociology Isaac William Martin and Monica Prasad 2014 Archived prepublication draft Posted with permission from the Annual Review of Sociology, Volume 40, copyright by Annual Reviews, http://www.annualreviews.org. When citing this paper, please cite to the final version of record: Martin IW, Prasad M. 2014. Taxes and fiscal sociology. Annu. Rev. Soc. 40: 331-345. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043229 The final version of record may be retrieved from this URL: http://arjournals.annualreviews.org/eprint/yYhz4GgQvV8WzZpkuhbH/full/10.1146/annurev- soc-071913-043229 INTRODUCTION Taxation is hardly a peripheral subject in sociology. Our canonical texts describe taxation as one of the most important factors that can foster or impede capitalist economic development and the reproduction of class inequality (Marx & Engels 2012 [1848], Weber 1978). Sociologists today regularly assign our students nineteenth-century texts that recommend progressive taxation as a means of “revolutionizing the mode of production” (Marx & Engels 2012 [1848], p. 60) or ameliorating the “abnormal” division of labor (Durkheim 1984 [1893], p. 310). Yet few of us train our students to follow these leads. It is not an exaggeration to say that the fields of development studies and stratification research ignored taxation altogether as they developed in twentieth-century American sociology (cf. Grusky 2008). This neglect not only severed sociology from some of its theoretical traditions, it also marginalized sociological discourse about poverty and inequality by cutting it off from the most salient policy debates about these issues in our time. Our goal in this review is to introduce sociologists to important contributions of the recent empirical literature on taxation. -

The Economic Sociology of Capitalism

1 THE ECONOMIC SOCIOLOGY OF CAPITALISM: AN INTRODUCTION AND AGENDA by Richard Swedberg Cornell University [email protected] revised version July 27, 2003 2 Capitalism is the dominant economic system in today’s world, and there appears to be no alternatives in sight.1 Socialism, its main competitor, has been weakened immeasurably by the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. Where socialism still prevails, such as in the People’s Republic of China, serious attempts are made to turn the whole economic system in a capitalist direction so that it will operate in a more efficient manner. “It doesn’t matter if the cat is white or black as long as it catches mice”, to cite Deng Xiaping (e.g. Becker 2000:52-3). While the superiority of capitalism as an economic system and growth machine has fascinated economists for centuries, this has not been the case with sociologists. For sociologists capitalism has mainly been of interest for its social effects – how it has led to class struggle, anomie, inequality and social problems in general. Capitalism as an economic system in its own right has been of much less interest. Some of this reaction has probably to do with the unfortunate division of labor that developed between economists and sociologists in the 19th century: economists studied the economy, and the sociologists society minus the economy. In this respect, as in so many others, sociology has essentially been a “left-over science” (Wirth 1948). 1 For inspiration to write this chapter I thank Victor Nee and for comments and help with information Mabel Berezin, Patrik Aspers, Filippo Barbera, Mark Chavez, Philippe Steiner and two anonymous reviewers. -

El Eterno Retorno De La Asabiyyah. Ibn Jaldún Y La Teología Política Contemporánea

Daimon. Revista Internacional de Filosofía, nº 76, 2019, pp. 139-153 ISSN: 1130-0507 (papel) y 1989-4651 (electrónico) http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/daimon/281091 El eterno retorno de la Asabiyyah. Ibn Jaldún y la teología política contemporánea The eternal return of the Asabiyyah. Ibn Khaldun and contemporary political theology GIOVANNI PATRIARCA* Resumen: Los profundos cambios geopolíticos Abstract: The geopolitical changes of recent de las últimas décadas, el papel destabilizador de decades, the consequences of the “Arab Spring”, las “primaveras árabes”, el proceso en curso de the ongoing process of rearrangement in the reestructuración del Oriente Medio han desviado Middle East have diverted public attention la atención general hacia el pensamiento político towards Islamic political thought. In a context islámico. En un contexto de crisis y desorienta- of crisis and confusion, the concept of asabiyyah ción, el concepto de la asabiyyah y una lectura and a contemporary reading of the philosophy of contemporánea de la filosofía de Ibn Jaldún son Ibn Khaldun play a significant role in the name fundamentales en el nombre de una interpretación of a modern interpretation of classical political moderna de la teología política clásica. theology. Palabras claves: Ciencia política, Historia de la Keywords: Political Science, Islamic Philosophy, filosofía islámica, Historia del pensamiento eco- History of Economic Thought, Comparative Phi- nómico, Filosofía de la historia, Filosofía compa- losophy, Political Theology. rada, Teología política. Introducción El valor ambivalente de las “primaveras árabes” —con su papel desestabilizador en todo el mundo islámico1— ha dado vida a procesos de reforma y contrarreforma, provocando una serie interminable de luchas internas en el intento de una “reformulación democrática” de la sociedad2. -

Towards a Critical Sociology and Political Economy of Public Finance

TOWARDS A CRITICAL SOCIOLOGY AND POLITICAL ECONOMY OF PUBLIC FINANCE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY CEYHUN GÜRKAN IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY SEPTEMBER 2010 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Meliha Altunışık Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. Ayşe Saktanber Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. Ahmet H. Köse Prof. Dr. H. Ünal Nalbantoğlu Co-Supervisor Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. H. Ünal Nalbantoğlu Prof. Dr. Ahmet H. Köse Assoc. Prof. Dr. Sibel Kalaycıoğlu Assist. Prof. Dr. Galip Yalman Assist. Prof. Dr. Nilgün Erdem I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Signature : iii ABSTRACT TOWARDS A CRITICAL SOCIOLOGY AND POLITICAL ECONOMY OF PUBLIC FINANCE Gürkan, Ceyhun Ph.D., Department of Sociology Supervisor : Prof. Dr. Hasan Ünal Nalbantoğlu Co-Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ahmet Haşim Köse September 2010, 305 pages The exploration of this thesis on public finance proceeds on two axes. -

Summer 2007) Page 2

VVVooolll... 666 ||| IIIsss... 333 ||| SSSuuummmmmmeeerrr 222000000777 AAccccoouunnttss AASSAA Eccoonnoommiicc Soocciioollooggyy Seeccttiioonn Neewwsslleetttteerr What’s in this issue? Welcome to the pre-ASA issue of Accounts! Crossing Disciplinary We hope that this issue of Accounts finds you well and enjoying both a restful and produc- Boundaries: tive summer. Feminist Economics and ES In this issue, we are pleased to continue a central discussion from previous newsletters— (Julie Nelson)……...……… 2 how economic sociologists jump over disciplinary fences and interact with other social sci- ence disciplines. In the first article, feminist economist, Julie Nelson, makes economic sociol- Economic Sociology Meets ogy’s criticism of economics look timid as she argues for incorporating feminist insights into Science and Technology our definition of economy. She argues that economic sociology shares too tight a connection Studies (Trevor Pinch)……..3 with neoclassical economics in terms of the subject matter on which it focuses. Next, Trevor Fiscal Sociology Conference Pinch calls for exploring the common ground between economic sociology and science and at Northwestern (Martin, technology studies. By sharing his research on synthesizers, Pinch makes clear how the two Mehrotra, and Prasad) …......4 fields need each other to shed light on both the material and social aspects underlying techno- Econ Soc at the World Bank: logical processes. Third, Isaac Martin, Ajay Mehrotra, and Monica Prasad report on a recent an Interview with Dr. Michael conference on fiscal sociology they helped put together at Northwestern. Fiscal sociology Woolcock (Chris Yenkey) …5 itself is composed of an array of social sciences—sociology, economics, anthropology, politi- cal science, history, and law. -

UNCORRECTED PROOF Original Article Explaining the Anti-Soviet Revolutions by State Breakdown Theory and Geopolitical Theory

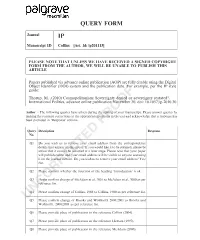

QUERY FORM Journal IP Manuscript ID Collins [Art. Id: ip201115] PLEASE NOTE THAT UNLESS WE HAVE RECEIVED A SIGNED COPYRIGHT FORM FROM THE AUTHOR, WE WILL BE UNABLE TO PUBLISH THIS ARTICLE Papers published via advance online publication (AOP) are fully citable using the Digital Object Identifier (DOI) system and the publication date. For example, per the IP style guide: Thorup, M. ,(2010) Cosmopolitanism: Sovereignty denied or sovereignty restated?. International Politics, advance online publication November 30, doi: 10.1057/ip.2010.30 Author :- The following queries have arisen during the editing of your manuscript. Please answer queries by making the requisite corrections at the appropriate positions in the text and acknowledge that a response has been provided in ‘Response’ column. Query Description Response No. Q1 Do you wish us to remove your email address from the correspondence details that appear on this proof? If you would like it to be retained, please be aware that it cannot be removed at a later stage. Please note that your paper will publish online and your email address will be visible to anyone accessing it on the journal website. Do you wish us to remove your email address? Yes/ No. Q2 Please confirm whether the insertion of the heading ‘Introduction’ is ok. Q3 Please confirm change of McAdam et al, 2001 to McAdam et al, 2000 as per reference list. Q4 Please confirm change of Collins, 1986 to Collins, 1980 as per reference list. UNCORRECTEDQ5 Please confirm change of Brooks and Wohlforth PROOF 2000/2001 to Brooks and Wolhforth, 2000/2001 as per reference list. -

Fiscal Sociology and Veblen's Critique of Capitalism: Insights for Social

ISSN: 1305-5577 DOI: 10.17233/sosyoekonomi.2020.01.17 Sosyoekonomi RESEARCH Date Submitted: 23.02.2019 ARTICLE Date Revised: 01.10.2019 2020, Vol. 28(43), 295-311 Date Accepted: 20.01.2020 Fiscal Sociology and Veblen’s Critique of Capitalism: Insights for Social Economics and the 2008 Crisis Ceyhun GÜRKAN (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8048-7175), Department of Public Finance, Ankara University, Turkey; e-mail: [email protected] Mali Sosyoloji ve Veblen’in Kapitalizm Eleştirisi: Sosyal İktisat ve 2008 Krizi için Düşünceler Abstract The purpose of this paper is to review fiscal sociology and Veblen’s critique of capitalism with an eye to developing new insights for social economics and the 2008 crisis. The paper adopts an interdisciplinary approach that blends history, political economy, politics, sociology, social philosophy, and ethics. The article demonstrates how old and new strands of fiscal sociology and Veblen’s economic sociology can be employed to develop a comprehensive understanding of history, present conditions and future of neoliberalism as well as its current crisis. The paper concludes that fiscal sociology and Veblen’s sociological and critical institutional economics have the great potential to develop new insights into critical social economics and the fiscal crisis of the state. Keywords : Fiscal Sociology, Veblen, 2008 Crisis, Capitalism, Neoliberalism. JEL Classification Codes : A14, B15, H00, Z1. Öz Bu yazı sosyal iktisada ve 2008 krizine dair yeni düşünceler geliştirmek üzere mali sosyolojiyi ve Veblen’in kapitalizm eleştirisini gözden geçirmektedir. Yazı tarihi, politik iktisadı, siyaset bilimini, toplumsal felsefeyi ve etiği harmanlayan disiplinlerarası bir yaklaşım benimsemektedir. Yazı mali sosyolojinin eski ve yeni tarzları ile Veblen’in iktisat sosyolojisinin neoliberalizmin tarihini, bugünkü koşullarını ve geleceğini ve ayrıca krizini anlamada nasıl kullanılabileceğinin yolunu göstermektedir. -

The New Fiscal Sociology

Dedicated to the memory of Charles Titly The New Fiscal Sociology TAXATION IN COMPARATIVE AND HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Edited by Isaac William Martin University of California, San Diego Ajay K. Mehrotra Indiana University - Bloomington Monica Prasad Northwestern University HiH CAMBRIDGE Qp ururwRsrrY PRESS 100 Christopher Howard PART TWO. TAXPAYER CONSENT workers with tax-favored dollars, those insurers develop a stake in tax expenditures. Employers themselves benefit because tax breaks for health and pension benefits help their companies attract and keep skilled workers, and may reduce demand for higher wages. The EITC picks up support from the National Restaurant Association and the American Hotel and Motel Association, whose members employ many low-wage workers. For these companies, the EITC acts like awagesubsidS paid by of Demanding Sacrifice: Applying taxpayers (Geewax 2005; Howard 1997; pierce 2005). 6 The Politics Thken together, all four chapters in this section prove that political and economic Insights from Fiscal sociology to the Study of AIDS elites have been central to tax policy in the United States since at least the 1930s. Policy and State Capacity The bigger change has been in the role of ordinary citizens. compared to the middle of the twentieth century, the public pays more attention to taxation, and EVAN S. LIEBERMAN elected officials care more about what the public thinks (campbell, chapter 3). The politics of taxation is no longer limited to the rich and powerful; it involves the entire population, with special attention to those who are politically active. INTRODUCTION: INSIGHTS FROM THE TAX STATE "the of a people, |oseph Schumpeter's stirring conclusion in a 1918 text, that spirit its cultural level, its social structure, the deeds its policy may prepare - all this and more is written in its fiscal history," serves as a mantra for alarge body of fiscal sociological scholarship.l However, the statement is, of course, hyperbole.