California Native Grasslands: a Historical Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural and Paleontological Resources

LSA ASSOCIATES, INC EBRPD WILDFIRE HAZARD REDUCTION AND RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN EIR JULY 2009 IV. SETTING, IMPACTS, AND MITIGATION E. CULTURAL AND PALEONTOLOGICAL RESOURCES E. CULTURAL AND PALEONTOLOGICAL RESOURCES This section provides an overview of the potential presence of cultural and paleontological resources in the Study Area of the East Bay Regional Parks District’s (EBRPD’s) Wildfire Hazard Reduction and Resource Management Plan (Plan) the proposed project. Also included is a discussion of potential impacts to such resources as a result of project implementation, as well as mitigation recommendations, as warranted. LSA Associates, Inc., provided EBRPD with a more detailed report concerning cultural and paleontological resources that is available for review at EBRPD’s Administrative Headquarters 2950 Peralta Oaks Court, Oakland CA. The lands managed by EBRPD are home to a wide range of cultural and paleontological resources. These resources contribute to the diverse historical and geological background of the San Francisco Bay Area, and are unique, nonrenewable community assets. Such resources on EBRPD lands include, but are not limited to, prehistoric and historical archaeological sites, historical buildings and structures, areas of traditional or religious value to contemporary communities, and fossiliferous geological deposits. 1. Setting This subsection describes the existing conditions for cultural and paleontological resources in the Study Area. The subsection begins with a description of the methods used to obtain background information, followed by an overview of the Study Area’s prehistory, ethnography, history, and paleontology/geology. A summary of recorded cultural and paleontological resources in the Study Area follows. Finally, the legislative context for cultural and paleontological resources is presented. -

And Others Environment

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 063 989 RC 006 197 AUTHOR Lundstrom, Donald; And Others TITLE Environment--A Way of Teaching (Grades K-12). INSTITUTION Alameda County ScLool Dept., Hayward, Calif. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 99p- AVAILABLE FROMCurriculum Library, Alameda County School Department, 224 West Winton Ave., Hayward, Calif. 94544 ($2.50) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Activity Learning; Agencies; Conservation Education; *Curriculum Guides; Fcology; Educational Legislation; Enrichment Activities; *Environmental Education; Librar,7 Materials; Mental Health; *Outdoor Education; PhysicIl Education; *Resource Materials; *Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS California ABSTRACT Resource information and ideas for curriculum programs related to thestudy of the environment are presented in tnis resource guile for elementary and secondary teachers.Activities in the oitioors ani action programsrepresentative of recent district and county activities in Alameda County, California, arediscussed. A list of resources, agencies, organizations, and programs,and a bibliography ot library materials are also provided. Theappendices include (I)the california State Education Code and (2)Federal and state laws anJ regulations pertaining to theenvironment. (NQ) 4 1 a U S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. _ EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF CC/LIGATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG INATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFI( IAL OFFICE OF EDU CATION POSITION CR POLICY 111IMMI=1.11. a 1.- I A ,z a i That whichcanbest be learned inside the classroom should be learn-6'd 11-i6t that whichcanbest be learned through direct experience outside the classroom, indirectcontact with the environment and life situations, should be learned there. -

Where's the Hayward Fault? a Green Guide to the Fault

Where's the Hayward Fault? A Green Guide to the Fault By Philip W. Stoffer This report describes self-guided field trips to one of North America's most dangerous earthquake faults—the Hayward Fault. Locations were chosen because of their easy access using mass transit and/or their significance relating to the natural and cultural history of the East Bay landscape. Open-File Report 2008-1135 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia 2008 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod/ Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Suggested citation: Stoffer, Philip W., 2008, Where’s the Hayward Fault? A green guide to the fault: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2008-1135, 88 p. [http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2008/1135/]. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. ii Table of Contents Introduction to This Guide .............................................................................................................1 -

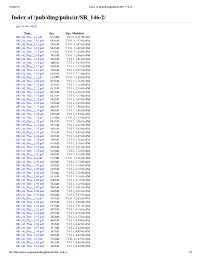

Aggregate Materials in the San Francisco-Monterey Bay Area

2/5/2019 Index of /pub/dmg/pubs/sr/SR_146-2/ Index of /pub/dmg/pubs/sr/SR_146-2/ [parent directory] Name Size Date Modified SR-146_Plate_2.1.pdf 3.0 MB 7/1/11, 2:11:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.10.pdf 638 kB 7/1/11, 12:47:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.11.pdf 250 kB 7/1/11, 12:47:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.12.pdf 662 kB 7/1/11, 12:48:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.13.pdf 628 kB 7/1/11, 12:50:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.14.pdf 743 kB 7/1/11, 12:50:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.15.pdf 534 kB 7/1/11, 1:01:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.16.pdf 480 kB 7/1/11, 1:03:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.17.pdf 660 kB 7/1/11, 1:19:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.18.pdf 730 kB 7/1/11, 2:07:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.19.pdf 645 kB 7/1/11, 2:12:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.2.pdf 2.0 MB 7/1/11, 12:24:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.20.pdf 477 kB 7/1/11, 2:16:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.21.pdf 361 kB 7/1/11, 2:18:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.22.pdf 612 kB 7/1/11, 2:35:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.23.pdf 427 kB 7/1/11, 2:36:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.24.pdf 642 kB 7/1/11, 2:47:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.25.pdf 542 kB 7/1/11, 2:49:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.26.pdf 665 kB 7/1/11, 2:53:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.27.pdf 596 kB 7/1/11, 2:56:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.28.pdf 542 kB 7/1/11, 2:56:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.29.pdf 699 kB 7/1/11, 2:57:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.3.pdf 1.8 MB 7/1/11, 12:32:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.30.pdf 683 kB 7/1/11, 2:58:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.31.pdf 512 kB 7/1/11, 3:03:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.32.pdf 483 kB 7/1/11, 3:03:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.33.pdf 371 kB 7/1/11, 3:08:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.34.pdf 515 kB 7/1/11, 3:09:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.35.pdf 440 kB 7/1/11, 3:10:00 AM SR-146_Plate_2.36.pdf 633 kB 7/1/11, 3:10:00 -

East Bay Regional Park District Resolution

N^ MASTER PLAN 1997 W EAST BAY REGIONAL PARK DISTRICT • •v * - • MASTER PLAN 1997 EAST BAY REGIONAL PARK DISTRICT & % dS- T^LtLT Adopted: December 17, 1996 • Resolution No: 1996-12-349 • • EBRPD Headquarters 2950 Peralta Oaks Court P.O. Box 538 I • Oakland, California 94605 — Dear Friends, It is with great pleasure that the Board of Directors presents the 1 997 East Bay Regional Park District Master Plan. This Master Plan pledges the continued implementation of the visions and ideals of the public spirited citizens who formed the District in 1 934 and dedicates this continued effort to those who have worked selflessly over the past 63 years to create and care for this extraordinary Regional Park System. The 1997 District Master Plan will guide us for the next decade, well into the 21st Century. Our hopes and dreams for the future of the East Bay Regional Park District are embodied in this plan. The Master Plan recognizes the two primary duties of the District: the conservation of our scenic, natural, and open space resources and the provision of needed recreation opportunities, and describes the process to find a proper balance between these responsibilities. The Master Plan also recognizes the need to expand our parks, trails, and services as a proper response to the need of our dynamic, diverse, and growing region. Many citizens worked countless hours on the preparation and review of this Master Plan. The Board of Directors deeply appreciates this public participation and we commit ourselves to continue to work with you, our neighbors and friends to provide the highest standard of resource conservation and recreational service for the citizens of Alameda and Contra Costa counties. -

Guide to Visiting California's Grasslands

Guide to Visiting California's Grasslands Guide to Visiting California's Grasslands California's native grasslands are incredibly diverse and biologically important ecosystems. Yet grasslands remain one of the most under-protected of California's vegetation types, and native grasslands have undergone the greatest percentage loss of any habitat type in the state--including much-publicized losses in wetland and riparian systems. The individual profiles in this Guide to Visiting California's Grasslands are written to open the readers' eyes to the diversity and natural beauty of native grasslands, to provide specific information about each site's ecology and management, and to make it possible for you to visit native grasses in the ground. All of the locations included are publicly accessible grasslands. The profiles will tell you how to reach the site, best times to visit, what to look for, and where you may find similar sites. You are encouraged to print the profile and take it with you when you visit. Elements of this guide were developed with the assistance of a LEGACI Grant from the Great Valley Center. Table of Contents Page 1… Alkali Sacaton Grassland--San Luis National Wildlife Refuge Complex, Kesterson Unit 4… Coastal Grassland--Tilden and Wildcat Canyon Regional Parks 7… Inner Coast Range Prairie--Bear Creek Botanical Management Area 10… Native Dune Grasslands--Asilomar State Beach 14… Purple Needlegrass Grassland--Lake Chabot Regional Park, Fairmont Ridge 17… Purple Needlegrass Grassland--Pacheco State Park, Pig Pond 20… Santa Rosa Plateau Ecological Reserve--Southwestern Riverside County 23… Serpentine Grassland--Redwood Regional Park, Skyline Serpentine Prairie 26… Tufted Hairgrass Grassland--Point Reyes National Seashore, "F" Ranch 28… Vernal Pool Grassland--Pixley Vernal Pools Preserve 31… Wagon Creek Research Natural Area--Los Padres National Forest Visiting Alkali Sacaton Grassland San Luis National Wildlife Refuge Complex, Kesterson Unit Location The San Luis National Wildlife Refuge is near Los Banos in the central San Joaquin Valley. -

Board Meeting Packet

August 10, 2021 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Board Meeting Packet SPECIAL NOTICE REGARDING PUBLIC PARTICIPATION AT THE EAST BAY REGIONAL PARK DISTRICT BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING SCHEDULED FOR TUESDAY, AUGUST 10, 2021 at 1:30 pm Pursuant to Governor Newsom’s Executive Order No. N-29-20, the East Bay Regional Park District Headquarters will not be open to the public and the Board of Directors and staff will be participating in the Board meetings via phone/video conferencing. Members of the public can listen and view the meeting in the following way: Via the Park District’s live video stream which can be found at https://youtu.be/eXBPpCkQmA4 Public comments may be submitted one of three ways: 1. Via email to Yolande Barial Knight, Clerk of the Board, at [email protected]. Email must contain in the subject line public comments – not on the agenda or public comments – agenda item #. It is preferred that these written comments be submitted by Monday, August 9, 2021 at 3:00 pm. 2. Via voicemail at (510) 544-2016. The caller must start the message by stating public comments – not on the agenda or public comments – agenda item # followed by their name and place of residence, followed by their comments. It is preferred that these voicemail comments be submitted by Monday, August 9, 2021 at 3:00 pm. 3. Live via zoom. If you would like to make a live public comment during the meeting this option is available through the virtual meeting platform: *Note: this virtual meeting platform link will let you into the https://zoom.us/j/89210940636 virtual meeting for the purpose of providing a public comment. -

Getting Settled in Berkeley

1. Getting Settled In Berkeley Getting to and around the Bay Area ............................................................................................2 California Resident Information ..................................................................................................5 (Register your vehicle, get a driver’s license or ID card, register to vote Exploring Berkeley…………. .......................................................................................................6 Bay Area Opportunities for Recreation and Reflection .............................................................7 Local Entertainment ......................................................................................................................9 Local Farmers’ Markets..............................................................................................................10 1 Getting to and around the Bay Area Getting to JST JST is located in Berkeley, California and is accessible by car, the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) subway system, and several AC Transit bus lines. Visitors arriving at San Francisco International Airport (SFO) or Oakland International Airport (OAK) may find Lyft or Uber their most convenient option (see page 4 for more details). BART is another good option that is also economical. From SFO, take BART directly from the airport’s SFO station. From the Oakland Airport, take the automated people-mover across from the arrivals gate to the BART Coliseum station. To reach your final destination, you may need to take an -

California Faces: Selections from the Bancroft Library Portrait Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf4z09p0qg Online items available California Faces: Selections from The Bancroft Library Portrait Collection Processed by California Heritage Digital Image Access Project staff in The Bancroft Library. The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. California Faces: Selections from Various 1 The Bancroft Library Portrait Collection California Faces: Selections from The Bancroft Library Portrait Collection Collection number: Various The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] Finding Aid Author(s): Processed by California Heritage Digital Image Access Project staff in The Bancroft Library. Finding Aid Encoded By: GenX Copyright 1997 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: California Faces: Selections from The Bancroft Library Portrait Collection Collection Number: Various Physical Description: 1,648 images selected from The Bancroft Library's Portrait Collection ; various sizes1648 digital objects (1,659 images) Repository: The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] Languages Represented: Collection materials are in English Access Collection is available for use. Publication Rights Some materials in these collections may be protected by the U.S. Copyright Law (Title 17, U.S.C.). In addition, the reproduction of some materials may be restricted by terms of University of California gift or purchase agreements, donor restrictions, privacy and publicity rights, licensing and trademarks. -

BANG MSS 95/76 C

BANG MSS 95/76 c Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Donated Oral Histories Collection JOYCE E. BURR: Memories of Years Preceding and During the Formation of the California Native Plant Society 1947-1966 An Interview Conducted By Mary Mead 1992 [In fulfillment of requirements for the Advanced Class in Oral History Methods and Techniques Vista College, Berkeley Instructor: Elaine Dorfman] Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Donated Oral Histories Collection JOYCE E. BURR: Memories of Years Preceding and During the Formation of the California Native Plant Society 1947-1966 An Interview Conducted By Mary Mead 1992 [In fulfillment of requirements for the Advanced Class in Oral History Methods and Techniques Vista College, Berkeley Instructor: Elaine Dorfman] University of California Berkeley JOYCE EIERMAN BURR 1992 Photograph taken by Mary Mead TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Planning Materials iii B. Introduction viii C. Interview History ix D. Transcript of Interviews 1 I. Joyce Burr: Personal Background 1 a. Early Childhood Memories 1 b. College Years at the University of Wisconsin. 3 c. Joyce Meets 'Doc' Burr 4 d. The Burrs Move to California 6 e. The Burrs Settle in El Cerrito 7 II. Activities Leading to the Development of CNPS . ... 9 a. The Tilden Botanic Garden and James Roof ... 9 b. Plans to Move the Botanic Garden 11 c. Groups Form in Defense of the Botanic Garden. 13 d. Mott Becomes Park District Manager 14 e. Mott's Vision for a New Botanic Garden Site . 15 f. James Roof 17 g. -

A Vision Achieved : Fifty Years of East Bay Regional Park District

AVISION ACHIEVED FiftyYears of East Bay Regional Park District Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/visionachievedfiOOstei AVISION ACHIEVED AVISION ACHIEVED FiftyYears of East Bay Regional Park District by Mimi Stein EAST BAY REGIONAL PARK DISTRICT Copyright © 1984 East Bay Regional Park District All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechan- ical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Published by the East Bay Regional Park District for its Fiftieth Anniversary. Printed in the United States of America by Braun-Brumfield, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan Design and Production: Matrix Productions Typesetting: Vera Allen Composition East Bay Regional Park District is grateful to the many photog- raphers who photographed the parks over the years. Credit for some of the photos used in this book could not be determined, but those photographers who can be credited include: Sal Brom- berger, p. 84: Jack Chinn, p. 50; M.L. Cohen, pp. 18, 24; Martin J. Cooney, pp. 53, 63, 67, 69, 74, 104; Cecil Davis, p. 68; A.J. Edwards, p. 38 bottom; Charles Haacker, pp. 72, 97; Andrew Ham, p. 25 bottom; Albert "Kayo" Harris, pp. 19 top, 21 left, 32, 35 bottom, 40 left and right, 42, 44; Ed Kirwan, p. 66 bottom; James La Cunha, p. 117; Luther Linkhart, p. 71: Nancy McKay, frontispiece, pp. 29, 58, 61-62, 75, 78, 82, 88-89, 94-95, 98, 100, 102-103, 105, 1 19; F.J. -

Mineral Land Classification : Aggregate Materials in the San Francisco

iilllll f i 5 iflillllllP! : iiSSiSi^ flip 111 P Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/minerallandclassOOstin ^ PHYSICAL SCIENCES MINERAL LAND CLASSIFICAT LIBRARY UC DAVIS I AGGREGATE MATERIALS IN THE SAN FRANCISCO-MONTEREY BAY AREA 1987 CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION DIVISION OF MINES AND GEOLOGY SPECIAL REPORT 146 Part II Classification of Aggregate Resource Areas SOUTH SAN FRANCISCO BAY PRODUCTION-CONSUMPTION REGION THE RESOURCES AGENCY STATE OF CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION GORDON K. VAN VLECK GEORGE DEUKMEJIAN RANDALL M. WARD SECRETARY FOR RESOURCES GOVERNOR DIRECTOR DIVISION OF MINES AND GEOLOGY JAMES F. DAVIS STATE GEOLOGIST SPECIAL REPORT 146 MINERAL LAND CLASSIFICATION: AGGREGATE MATERIALS IN THE SAN FRANCISCO - MONTEREY BAY AREA Part II Classification of Aggegate Resource Areas South San Francisco Bay Production-Consumption Region By Melvin C. Stinson Michael W. Manson and John J. Plappert Assisted by Edward J. Bortugno E. Levis Russell V. Miller Ralph V. Loyd Michael A. Silva Under the Direction of James F. Davis, Rudolph G. Strand, and David J. Beeby 1987 CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION DIVISION OF MINES AND GEOLOGY 1416 Ninth Street, Room 1341 Sacramento, CA 95814 FOREWORD Special Report 146, "Mineral Land Classification of the San Francisco-Monterey Bay Area," is the first analysis of mineral resources in the San Francisco-Monterey Bay area to be developed by the Division of Mines and Geology under authority of the Surface Mining and Reclamation Act of 1975 (SMARA). This classification is provided to the State Mining and Geology Board for transmittal to the local governments which regulate land use in this region, and for consideration of areas, if any, to be designated as regionally significant.