3 the Informal Settlements in Metro Manila 12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 16Th Congress

CongressWatch Report No. 176 Report No. 176 17 June 2013 The 16th Congress In the Senate The 16th Congress will open on 22 July, the same day that President Benigno Aquino III delivers his fourth State-of-the-Nation Address (SONA). The Senate will likely have a complete roster for the first time since the 12th Congress. It may be recalled that during the 2001 elections, 13 senators were elected, with the last placer serving the unfinished term of Sen. Teofisto Guingona who was then appointed as vice president. The chamber had a full roll of 24 senators for only a year, due to the appointment of Sen. Blas Ople as Foreign Affairs Secretary on 23 July 2002, and due to the passing of Sen. Renato Cayetano on 25 June 2003. The 11th, 13th, 14th, and 15th Congresses did not have full membership, primarily because a senator did not complete the six-year term due to being elected to another post.1 In the 2013 midterm elections last May, all of the six senators seeking re-election made it to the top 12, while two were members of the House of Representatives in the 15th Congress. The twelve senators-elect are: SENATOR PARTY PREVIOUS POSITION 1. ANGARA, Juan Edgardo M. LDP Representative (Aurora, lone) 2. AQUINO, Paolo Benigno IV A. LP Former chairperson, National Youth Commission 3. BINAY-ANGELES, Nancy S. UNA 4. CAYETANO, Alan Peter S. NP Outgoing senator 5. EJERCITO, Joseph Victor G. UNA Representative (San Juan City, lone) 6. ESCUDERO, Francis Joseph G. Independent Outgoing senator 7. -

Comprehensive Land Use Plan 2016 - 2025

COMPREHENSIVE LAND USE PLAN 2016 - 2025 PART 3: SECTORAL PROFILE 3.1. INFRASTRUCTURE, FACILITIES AND UTILITIES 3.1.1. Flood Control Facilities 3.1.1.1. “Bombastik” Pumping Stations Being a narrow strip of land with a relatively flat terrain and with an aggregate shoreline of 12.5 kilometers that is affected by tidal fluctuations, flooding is a common problem in Navotas City. This is aggravated by pollution and siltation of the waterways, encroachment of waterways and drainage right-of-ways by legitimate and informal settlers, as well as improper waste disposal. The perennial city flooding inevitably became a part of everyday living. During a high tide with 1.2 meter elevation, some parts of Navotas experience flooding, especially the low-lying areas along the coast and riverways. As a mitigating measure, the city government - thru the Local Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Office - disseminates information about the heights of tides for a specific month. This results in an increased awareness among the residents on the time and date of occurrence of high tide. During rainy days, flooding reach higher levels. The residents have already adapted to this situation. Those who are well-off are able to install their own preventive measures, such as upgrading their floorings to a higher elevation. During the term of the then Mayor and now Congressman, Tobias M. Tiangco, he conceptualized a project that aims to end the perennial flooding in Navotas. Since Navotas is surrounded by water, he believed that enclosing the city to prevent the entry of water during high tide would solve the floods. -

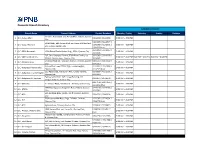

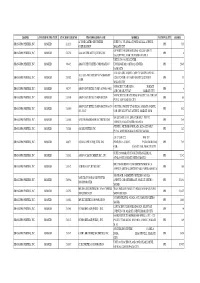

Domestic Branch Directory BANKING SCHEDULE

Domestic Branch Directory BANKING SCHEDULE Branch Name Present Address Contact Numbers Monday - Friday Saturday Sunday Holidays cor Gen. Araneta St. and Aurora Blvd., Cubao, Quezon 1 Q.C.-Cubao Main 911-2916 / 912-1938 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 912-3070 / 912-2577 / SRMC Bldg., 901 Aurora Blvd. cor Harvard & Stanford 2 Q.C.-Cubao-Harvard 913-1068 / 912-2571 / 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Sts., Cubao, Quezon City 913-4503 (fax) 332-3014 / 332-3067 / 3 Q.C.-EDSA Roosevelt 1024 Global Trade Center Bldg., EDSA, Quezon City 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 332-4446 G/F, One Cyberpod Centris, EDSA Eton Centris, cor. 332-5368 / 332-6258 / 4 Q.C.-EDSA-Eton Centris 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM EDSA & Quezon Ave., Quezon City 332-6665 Elliptical Road cor. Kalayaan Avenue, Diliman, Quezon 920-3353 / 924-2660 / 5 Q.C.-Elliptical Road 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 924-2663 Aurora Blvd., near PSBA, Brgy. Loyola Heights, 421-2331 / 421-2330 / 6 Q.C.-Katipunan-Aurora Blvd. 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Quezon City 421-2329 (fax) 335 Agcor Bldg., Katipunan Ave., Loyola Heights, 929-8814 / 433-2021 / 7 Q.C.-Katipunan-Loyola Heights 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Quezon City 433-2022 February 07, 2014 : G/F, Linear Building, 142 8 Q.C.-Katipunan-St. Ignatius 912-8077 / 912-8078 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Katipunan Road, Quezon City 920-7158 / 920-7165 / 9 Q.C.-Matalino 21 Tempus Bldg., Matalino St., Diliman, Quezon City 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 924-8919 (fax) MWSS Compound, Katipunan Road, Balara, Quezon 927-5443 / 922-3765 / 10 Q.C.-MWSS 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 922-3764 SRA Building, Brgy. -

Squatters of Capital: Regimes of Dispossession and the Production of Subaltern Sites in Urban Land Conflicts in the Philippines Christopher John “CJ” Chanco May 2015

Land grabbing, conflict and agrarian‐environmental transformations: perspectives from East and Southeast Asia An international academic conference 5‐6 June 2015, Chiang Mai University Conference Paper No. 23 Squatters of Capital: Regimes of Dispossession and the production of subaltern sites in urban land conflicts in the Philippines Christopher John “CJ” Chanco May 2015 BICAS www.plaas.org.za/bicas www.iss.nl/bicas In collaboration with: Demeter (Droits et Egalite pour une Meilleure Economie de la Terre), Geneva Graduate Institute University of Amsterdam WOTRO/AISSR Project on Land Investments (Indonesia/Philippines) Université de Montréal – REINVENTERRA (Asia) Project Mekong Research Group, University of Sydney (AMRC) University of Wisconsin-Madison With funding support from: Squatters of Capital: Regimes of Dispossession and the production of subaltern sites in urban land conflicts in the Philippines by Christopher John “CJ” Chanco Published by: BRICS Initiatives for Critical Agrarian Studies (BICAS) Email: [email protected] Websites: www.plaas.org.za/bicas | www.iss.nl/bicas MOSAIC Research Project Website: www.iss.nl/mosaic Land Deal Politics Initiative (LDPI) Email: [email protected] Website: www.iss.nl/ldpi RCSD Chiang Mai University Faculty of Social Sciences, Chiang Mai University Chiang Mai 50200 THAILAND Tel. 6653943595/6 | Fax. 6653893279 Email : [email protected] | Website : http://rcsd.soc.cmu.ac.th Transnational Institute PO Box 14656, 1001 LD Amsterdam, The Netherlands Tel: +31 20 662 66 08 | Fax: +31 20 675 71 76 Email: [email protected] | Website: www.tni.org May 2015 Published with financial support from Ford Foundation, Transnational Institute, NWO and DFID. -

List of Ecpay Cash-In Or Loading Outlets and Branches

LIST OF ECPAY CASH-IN OR LOADING OUTLETS AND BRANCHES # Account Name Branch Name Branch Address 1 ECPAY-IBM PLAZA ECPAY- IBM PLAZA 11TH FLOOR IBM PLAZA EASTWOOD QC 2 TRAVELTIME TRAVEL & TOURS TRAVELTIME #812 EMERALD TOWER JP RIZAL COR. P.TUAZON PROJECT 4 QC 3 ABONIFACIO BUSINESS CENTER A Bonifacio Stopover LOT 1-BLK 61 A. BONIFACIO AVENUE AFP OFFICERS VILLAGE PHASE4, FORT BONIFACIO TAGUIG 4 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HEAD OFFICE 170 SALCEDO ST. LEGASPI VILLAGE MAKATI 5 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BF HOMES 43 PRESIDENTS AVE. BF HOMES, PARANAQUE CITY 6 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_BETTER LIVING 82 BETTERLIVING SUBD.PARANAQUE CITY 7 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_COUNTRYSIDE 19 COUNTRYSIDE AVE., STA. LUCIA PASIG CITY 8 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_GUADALUPE NUEVO TANHOCK BUILDING COR. EDSA GUADALUPE MAKATI CITY 9 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_HERRAN 111 P. GIL STREET, PACO MANILA 10 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_JUNCTION STAR VALLEY PLAZA MALL JUNCTION, CAINTA RIZAL 11 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_RETIRO 27 N.S. AMORANTO ST. RETIRO QUEZON CITY 12 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP_SUMULONG 24 SUMULONG HI-WAY, STO. NINO MARIKINA CITY 13 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP 10TH 245- B 1TH AVE. BRGY.6 ZONE 6, CALOOCAN CITY 14 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP B. BARRIO 35 MALOLOS AVE, B. BARRIO CALOOCAN CITY 15 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP BUSTILLOS TIWALA SA PADALA L2522- 28 ROAD 216, EARNSHAW BUSTILLOS MANILA 16 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CALOOCAN 43 A. MABINI ST. CALOOCAN CITY 17 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP CONCEPCION 19 BAYAN-BAYANAN AVE. CONCEPCION, MARIKINA CITY 18 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP JP RIZAL 529 OLYMPIA ST. JP RIZAL QUEZON CITY 19 TIWALA SA PADALA TSP LALOMA 67 CALAVITE ST. -

Classified Ads Ng PEOPLE’S BALITA 4 Ay Dapat Ipabatid Sa Amin Sa Mismong Araw Na Nalathala Ang Anunsiyo

ANG mga error at omisyon sa Classified Ads ng PEOPLE’S BALITA 4 ay dapat ipabatid sa amin sa mismong araw na nalathala ang anunsiyo. Hindi CLASSIFIED ADS pananagutan ng PEOPLE’S BALITA CLASSIFIED ADS ang hihigit sa isang maling insertion FOR INQUIRIES CALL: +639189484771 ng anumang partikular na ad na hindi DECEMBER 4, 2020 agad ipinagbigay-alam sa amin. re-setting of the case on the following week of any point in the PHILIPPINES accessible to TIN B. DELGRA III, Chairman, this 29th a Transport Network Vehicle Service EXTRAJUDICIAL the same day. motor vehicle traffic and vice versa with the day of SEPTEMBER 2020. LORENA DAYO date, applicant/s shall publish this Notice once Applicant/s. in ONE (1) daily newspaper of general cir- SETTLEMENT OF ESTATE WITNESS the Honorable ATTY. MAR- use of ONE (1) unit/s. culation in Luzon. TIN B. DELGRA III, Chairman, this 12th NOTICE is hereby given that this applica- ATTY. JENNIFER LEAH P. ROJAS x- - - - - - - - - - - - - -x Parties opposed to the granting of the Notice is hereby given that the estate of the day of AUGUST 2020. tion will be heard by this Board on JANU- Attorney IV NOTICE OF HEARING application must file their written opposi- late DOMINADOR G. VILLIAVICENCIO ARY 14, 2021 at 1:00 p.m. at its office at the Hearing Officer Applicant is a grantee of a Certificate of tions supported by documentary evidence on who died on October 11, 2020 in Marikina City, ATTY. JENNIFER LEAH P. ROJAS above address. Public Convenience to operate a Transport Network Vehicle Service within METRO MA- or before the above date furnishing a copy Attorney IV At least FIVE (5) days prior to the above of the same to the applicant/s and may if they left his House and Lot situated at Blk 1 Lot 7, Hearing Officer date, applicant/s shall publish this Notice once NILA and its nearby provinces accessible to Income St. -

Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper Mckinley Rd

Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper McKinley Rd. McKinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel. No. 238-6300 Website: http://www.ipophil.gov.ph e-mail: [email protected] Publication Date: February 21, 2017 1 ALLOWED MARKS PUBLISHED FOR OPPOSITION .................................................................................................... 2 1.1 ALLOWED NATIONAL MARKS ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper McKinley Rd. McKinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel. No. 238-6300 Website: http://www.ipophil.gov.ph e-mail: [email protected] Publication Date: February 21, 2017 1 ALLOWED MARKS PUBLISHED FOR OPPOSITION 1.1 Allowed national marks Application No. Filing Date Mark Applicant Nice class(es) Number 21 16; 17; 19; 20; 27 1 4/1914/00014451 November PARADIGM ANTHONY L. GO [PH] and45 2014 2 2 4/1914/00505681 December STROMER Thömus Holding AG [CH] 25 2014 27 January AUTOMATIC SWITCH 3 4/1916/00500482 ASCO EXPRESS 39 2016 COMPANY [US] 8 October EDADES TOWER AND ROCKWELL LAND 4 4/2010/00011100 36 and37 2010 GRADEN VILLAS CORPORATION [PH] 13 June 5 4/2013/00006818 DELTEK DELTEK, INC. [US] 9 and42 2013 13 June 6 4/2013/00006819 DELTEK DELTEK, INC. [US] 35; 38; 41 and45 2013 XYLOMEN 30 January 7 4/2014/00001273 SAFE BLASTER PARTICIPATIONS, S.A.R.L 9 and28 2014 [LU] 5 February 8 4/2014/00001478 G4 LG ELECTRONICS INC. [KR] 9 2014 ALL STARS A 21 May SHEPHERD`S VOICE 9 4/2014/00006350 GENERATION THAT 16 2014 PUBLICATIONS [PH] SHINES FOR CHRIST 18 June MEDCHOICE PHARMA, INC. 10 4/2014/00007647 MEDCHOICE 35 and40 2014 [PH] 17 JANGCHUNGDONG WANG 11 4/2014/00011602 September 43 JOKBAL. -

Death by Lethal Injection

DEATH BY LETHAL INJECTION By Alan C. Atkins The truth about Englishman Albert Wilson’s sentence and eventual acquittal in the Philippines. 1 Contents A Remarkable Story 4 Suny’s Release 5 Foreign Travel A Warning 6 INTRODUCTION Story by Alan Atkins 6 1 A Storm Is Brewing 8 2 A Very Bad Day 12 3 Pio’s Mistake 15 4 Paradise lost 19 5 Serious Bargaining 25 6 A Cry For Help 29 7 Nica’s “Credible” Story On One Rape 34 8 All Is Solved Moran Arrives 44 9 Oh Dear: Nica Proven To Be A Liar 48 10 Philippine Hysterla Explained 49 11 The Medical Evidence 53 12 Nica’s Brother Takes The Stand 57 13 Nica Tells Of Other Alleged Rapes 60 14 More Expert Opinion Ignored 65 15 With Friends Like These 67 16 Pathetic Defense Summation 73 17 The Day Of The Verdict 74 18 How ‘Mission Nigh Impossible’ Begins 77 19 Team Formed Contact Made 80 20 Competency Questioned 83 21 Fifirst To Die - Leo Echegaray 88 22 The Helplessness Of The Catholic Church 94 23 Walter Tries To Help, Again 104 24 A Visit To Prison 109 25 Appeals For Financial Assistance 115 26 Problems In Prison 119 27 Meeting Some Of The Family 122 28 Inept Lawyers Force Amateurs To Write A Brief 130 29 Confession Of Wilson’s Lawyer 136 30 Walter ‘Mitty’ Moran Reveals How Dangerous He Really 138 2 31 The Final Appellant’s Brief 147 32 Questionable Behavior At The Court 152 33 Suspicious Actions Revealed 158 34 Solcitor-General Recommends Acquittal 168 35 ‘More Leaks Than A Plumber Can Fix’ 176 36 A Soiled Victory 182 37 The Storm Breaks 186 38 A Little Bit Guilty ? 190 Addendum 1 Appealing For Funds 193 Addendum 2 Letters From Wilson 200 Addendum 3 British Embassy Letters 221 Addendum 4 Some Letters To The Press 243 Index 247 Symbols 247 3 A Remarkable Story This is a remarkable true story of a happening that took place in the Philippines in 1996. -

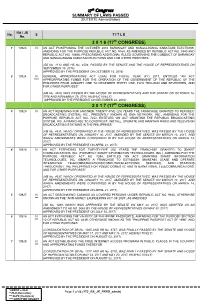

17Th Congress SUMMARY of LAWS PASSED (DUTERTE Administration)

17th Congress SUMMARY OF LAWS PASSED (DUTERTE Administration) RA / JR No. S T I T L E No. 2 0 1 6 (17th CONGRESS) 1 10923 N AN ACT POSTPONING THE OCTOBER 2016 BARANGAY AND SANGGUNIANG KABATAAN ELECTIONS, AMENDING FOR THE PURPOSE REPUBLIC ACT NO. 9164, AS AMENDED BY REPUBLIC ACT NO. 9340 AND REPUBLIC ACT NO. 10656, PRESCRIBING ADDITIONAL RULES GOVERNING THE CONDUCT OF BARANGAY AND SANGGUNIANG KABATAAN ELECTIONS AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES (SB No. 1112 AND HB No. 3504, PASSED BY THE SENATE AND THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ON SEPTEMBER 13, 2016) (APPROVED BY THE PRESIDENT ON OCTOBER 15, 2016) 2 10924 N GENERAL APPROPRIATIONS ACT (GAA) FOR FISCAL YEAR (FY) 2017, ENTITLED “AN ACT **** APPRORPRIATING FUNDS FOR THE OPERATION OF THE GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPINES FROM JANUARY ONE TO DECEMBER THIRTY ONE, TWO THOUAND AND SEVENTEEN, AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES” (HB No. 3408, WAS PASSED BY THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES AND THE SENATE ON OCTOBER 19, 2016 AND NOVEMBER 28, 2016, RESPECTIVELY) (APPROVED BY THE PRESIDENT ON DECEMBER 22, 2016) 2 0 1 7 (17th CONGRESS) 3 10925 N AN ACT RENEWING FOR ANOTHER TWENTY-FIVE (25) YEARS THE FRANCHISE GRANTED TO REPUBLIC BROADCASTING SYSTEM, INC., PRESENTLY KNOWN AS GMA NETWORK, INC., AMENDING FOR THE PURPOSE REPUBLIC ACT NO. 7252, ENTITLED “AN ACT GRANTING THE REPUBLIC BROADCASTING SYSTEM, INC. A FRANCHISE TO CONSTRUCT, INSTALL, OPERATE AND MAINTAIN RADIO AND TELEVISION BROADCASTING STATIONS IN THE PHILIPPINES” (HB No. 4631, WHICH ORIGINATED IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, WAS PASSED BY THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ON JANUARY 16, 2017, AMENDED BY THE SENATE ON MARCH 13, 2017, AND WHICH AMENDMENTS WERE CONCURRED IN BY THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ON MARCH 14, 2017) (APPROVED BY THE PRESIDENT ON APRIL 21, 2017) 4 10926 N AN ACT EXTENDING FOR TWENTY-FIVE (25) YEARS THE FRANCHISE GRANTED TO SMART COMMUNICATIONS, INC. -

Shang List 052316

ISSUER STOCKHOLDER TYPE STOCKHOLDER NO STOCKHOLDER NAME ADDRESS NATIONALITY SHARES A. T. DE CASTRO SECURITIES SUITE 701, 7/F AYALA TOWER AYALA AVENUE, SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 211123 PH 535 CORPORATION MAKATI CITY G/F FORTUNE LIFE BUILDING 162 LEGASPI ST., SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 211238 AAA SOUTHEAST EQUITIES, INC. PH 8 LEGASPI VILL. MAKATI, METRO MANILA UNIT E 2904-A PSE CENTER SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 80442 ABACUS SECURITIES CORPORATION EXCHANGE RD., ORTIGAS CENTER PH 2,049 PASIG CITY ALL ASIA SEC. MGMT. CORP. 7/F SYCIP-LAW ALL ALL ASIA SECURITIES MANAGEMENT SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 211322 ASIA CENTER 105 PASEO DE ROXAS STREET PH 35 CORP. MAKATI CITY 5/F PACIFIC STAR BLDG., MAKATI SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 80257 AMON SECURITIES CORP. A/C#001-54011 PH 6 AVE COR GIL PUYAT MAKATI CITY 5/F PACIFIC STAR BUILDING MAKATI AVE. COR. GIL SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 211303 AMON SECURITIES CORPORATION PH 98 PUYAT AVE MAKATI CITY AMON SECURITIES CORPORATION A/C # 10TH FLR., PACIFIC STAR BLDG. MAKATI AVENUE, SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 211050 PH 982 001-33247 COR. SEN GIL PUYAT AVENUE, MAKATI, M. M. 3/F ASIAN PLAZA 1, SENATOR GIL J. PUYAT SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 211014 ANSCOR HAGEDORN SECURITIES INC PH 285 AVENUE, MAKATI METRO MANILA 9TH FLR., METROBANK PLAZA BLDG SEN GIL J. SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 211244 ASI SECURITIES, INC. PH 142 PUYAT AVENUE MAKATI, METRO MANILA A/C-CAXN1222 RM. 207 SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. BROKER 80673 ASIAN CAPITAL EQUITIES, INC. PENINSULA COURT, PASEO DE ROXAS PH 785 COR., MAKATI AVE., MAKATI CITY SUITE 210 MAKATI STOCK EXCHANGE BLDG., SHANG PROPERTIES, INC. -

2020 Acas Website Updating Part2.Xlsx

UNITED COCONUT PLANTERS BANK List of Branches as of January 2021 NO. BRANCH NAME ADDRESS 1 10TH AVENUE CALOOCAN 10th Avenue corner A. Mabini Street, Caloocan City 2 32ND STREET BGC F1 Building, 32nd Street Bonifacio Global City, Taguig 3 ACROPOLIS Units 5, 6, & 7 Village Center, 187 E. Rodriguez Jr. Avenue, Bagumbayan, Quezon City 4 AGUIRRE East Offices Building, 114 Aguirre Street, Legaspi Village, Makati City 5 ALABANG Civic Prime Building, Civic Drive corner Market Drive, Filinvest Corporate City, Alabang, Muntinlupa City 6 ANGELES Second Floor, UCPB Building, Sto. Rosario corner Plaridel Street, Angeles City 7 ANNAPOLIS Atlanta Center Building, 31 Annapolis St., Greenhills, San Juan 8 ANONAS Hi-top Supermart, Aurora Boulevard corner F. Castillo Street, Project 4, Quezon City 9 ANTIPOLO Circumferential Road, Barangay San Roque, Antipolo City 10 AQUINO AVENUE Freight Building, NAIA Avenue, Parañaque City 11 ARANETA AVENUE Doña Nena Building 425 Araneta Avenue corner Bayani Street Brgy Dona Imelda Quezon City 12 ASEANA CITY Ground Floor,Sole Mare Parksuites,Bradco Avenue Aseana Business Park,Paranaque City 13 AURORA BOULEVARD UCPB Building 725 Aurora Boulevard, New Manila, Quezon City 14 AYALA G/F BPI Philamlife Bldg. 6811 Ayala Ave. Makati City 15 BACLARAN UCPB Building, 4010 Airport Road, Baclaran, Parañaque City 16 BAGUIO UCPB Building, G. Calderon & T. Claudio Streets, Baguio City 17 BAJADA Ground Floor D'Leonor Hotel BLDG., J.P Laurel Avenue, Bajada, Davao City 8000 18 BALAGTAS Roma Building, 491 McArthur Highway, San Juan, Balagtas, Bulacan 19 BALANGA UCPB Building, Lot 5 Block 17 Don Manuel Banzon Avenue, Balanga City, Bataan 20 BALIUAG PVR Building, Benigno S. -

710Th SOW-PAF: Cooperatives, Strong Allies to End Insurgency, Repealing for the Purpose By: Marilyn D

COOPS ‘ STORIES OF SUCCESS-HIGHLIGHTS COOP MONTH CELEBRATIONStory on P. 6 CDA Completes Board of Administrators; Welcomes Administrator for Visayas Prior to passing of Re- public Act No. 11364 known as an Act Reorganizing and Strengthening the Coopera- tive Development Authority, 710th SOW-PAF: Cooperatives, Strong Allies to End Insurgency, Repealing for the Purpose By: Marilyn D. Eso Republic Act No. 6939, Cre- 2019, BGEN EDWARD L LIBAGO AFP, ating The Cooperative De- Wing Commander, 710th Special Oper- velopment Authority, the CDA ations Wing of the Philippine Air Force, completed the six (6) Board recognized the significant contributions of Administrators for Luzon, and the support system of the cooper- Visayas, and Mindanao in the ative movement to end insurgency par- person Administrator Vidal ticularly on neutralizing the activities of Dumindin Villanueva III. the New People’s Army (NPA) and other Administrator Villan- leftist group in their area of responsibili- ueva was appointed as the ty. new CDA Administrator for BGEN LIBAGO acknowledged the Visayas by His Excellency President Rodrigo Roa Duterte on Au- that the cooperative movement has gust 13, 2019. The CDA family warmly welcomed him with full of trust been of great help to the military in iden- and enthusiasm and assured him to support all his undertakings for the Nasugbo, Batangas – tifying the possible presence of the NPA growth and development of the authority and the cooperative sector. During the celebration of the 16th members in their area. All cooperative Adm. Villanueva is a 4th year Bachelor of Laws student at Gullas Batangas Industrial Security Alli- members have become allies of the School of Law of the University of the Visayas in Cebu City.