Scott Frank, Screenwriter and Director, Sat Down with MIP for an Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elmore Leonard, 1925-2013

ELMORE LEONARD, 1925-2013 Elmore Leonard was born October 11, 1925 in New Orleans, Louisiana. Due to his father’s position working for General Motors, Leonard’s family moved numerous times during his childhood, before finally settling in Detroit, MI in 1934. Leonard went on to graduate high school in Detroit in 1943, and joined the Navy, serving in the legendary Seabees military construction unit in the Pacific theater of operations before returning home in 1946. Leonard then attended the University of Detroit, majoring in English and Philosophy. Plans to assist his father in running an auto dealership fell through on his father’s early death, and after graduating, Leonard took a job writing for an ad agency. He married (for the first of three times) in 1949. While working his day job in the advertising world, Leonard wrote constantly, submitting mainly western stories to the pulp and/or mens’ magazines, where he was establishing himself with a strong reputation. His stories also occasionally caught the eye of the entertainment industry and were often optioned for films or television adaptation. In 1961, Leonard attempted to concentrate on writing full-time, with only occasional free- lance ad work. With the western market drying up, Leonard broke into the mainstream suspense field with his first non-western novel, The Big Bounce in 1969. From that point on, his publishing success continued to increase – with both critical and fan response to his works helping his novels to appear on bestseller lists. His 1983 novel La Brava won the Edgar Award for best mystery novel of the year. -

Executive Producer)

PRODUCTION BIOGRAPHIES STEVEN SODERBERGH (Executive Producer) Steven Soderbergh has produced or executive-produced a wide range of projects, most recently Gregory Jacobs' Magic Mike XXL, as well as his own series "The Knick" on Cinemax, and the current Amazon Studios series "Red Oaks." Previously, he produced or executive-produced Jacobs' films Wind Chill and Criminal; Laura Poitras' Citizenfour; Marina Zenovich's Roman Polanski: Odd Man Out, Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired, and Who Is Bernard Tapie?; Lynne Ramsay's We Need to Talk About Kevin; the HBO documentary His Way, directed by Douglas McGrath; Lodge Kerrigan's Rebecca H. (Return to the Dogs) and Keane; Brian Koppelman and David Levien's Solitary Man; Todd Haynes' I'm Not There and Far From Heaven; Tony Gilroy's Michael Clayton; George Clooney's Good Night and Good Luck and Confessions of a Dangerous Mind; Scott Z. Burns' Pu-239; Richard Linklater's A Scanner Darkly; Rob Reiner's Rumor Has It...; Stephen Gaghan'sSyriana; John Maybury's The Jacket; Christopher Nolan's Insomnia; Godfrey Reggio's Naqoyqatsi; Anthony and Joseph Russo's Welcome to Collinwood; Gary Ross' Pleasantville; and Greg Mottola's The Daytrippers. LODGE KERRIGAN (Co-Creator, Executive Producer, Writer, Director) Co-Creators and Executive Producers Lodge Kerrigan and Amy Seimetz wrote and directed all 13 episodes of “The Girlfriend Experience.” Prior to “The Girlfriend Experience,” Kerrigan wrote and directed the features Rebecca H. (Return to the Dogs), Keane, Claire Dolan and Clean, Shaven. His directorial credits also include episodes of “The Killing” (AMC / Netflix), “The Americans” (FX), “Bates Motel” (A&E) and “Homeland” (Showtime). -

Suggestions for Top 100 Family Films

SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS Title Cert Released Director 101 Dalmatians U 1961 Wolfgang Reitherman; Hamilton Luske; Clyde Geronimi Bee Movie U 2008 Steve Hickner, Simon J. Smith A Bug’s Life U 1998 John Lasseter A Christmas Carol PG 2009 Robert Zemeckis Aladdin U 1993 Ron Clements, John Musker Alice in Wonderland PG 2010 Tim Burton Annie U 1981 John Huston The Aristocats U 1970 Wolfgang Reitherman Babe U 1995 Chris Noonan Baby’s Day Out PG 1994 Patrick Read Johnson Back to the Future PG 1985 Robert Zemeckis Bambi U 1942 James Algar, Samuel Armstrong Beauty and the Beast U 1991 Gary Trousdale, Kirk Wise Bedknobs and Broomsticks U 1971 Robert Stevenson Beethoven U 1992 Brian Levant Black Beauty U 1994 Caroline Thompson Bolt PG 2008 Byron Howard, Chris Williams The Borrowers U 1997 Peter Hewitt Cars PG 2006 John Lasseter, Joe Ranft Charlie and The Chocolate Factory PG 2005 Tim Burton Charlotte’s Web U 2006 Gary Winick Chicken Little U 2005 Mark Dindal Chicken Run U 2000 Peter Lord, Nick Park Chitty Chitty Bang Bang U 1968 Ken Hughes Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, PG 2005 Adam Adamson the Witch and the Wardrobe Cinderella U 1950 Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson Despicable Me U 2010 Pierre Coffin, Chris Renaud Doctor Dolittle PG 1998 Betty Thomas Dumbo U 1941 Wilfred Jackson, Ben Sharpsteen, Norman Ferguson Edward Scissorhands PG 1990 Tim Burton Escape to Witch Mountain U 1974 John Hough ET: The Extra-Terrestrial U 1982 Steven Spielberg Activity Link: Handling Data/Collecting Data 1 ©2011 Film Education SUGGESTIONS FOR TOP 100 FAMILY FILMS CONT.. -

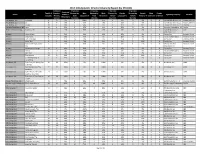

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By STUDIO)

2017 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by STUDIO) Combined # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes # Episodes Combined Total # of Female + Directed by Male Directed by Male Directed by Female Directed by Female Male Female Studio Title Female + Signatory Company Network Episodes Minority Male Caucasian % Male Minority % Female Caucasian % Female Minority % Unknown Unknown Minority % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority A+E Studios, LLC Knightfall 2 0 0% 2 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC History Channel A+E Studios, LLC Six 8 4 50% 4 50% 1 13% 3 38% 0 0% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC History Channel A+E Studios, LLC UnReal 10 4 40% 6 60% 0 0% 2 20% 2 20% 0 0 Frank & Bob Films II, LLC Lifetime Alameda Productions, LLC Love 12 4 33% 8 67% 0 0% 4 33% 0 0% 0 0 Alameda Productions, LLC Netflix Alcon Television Group, Expanse, The 13 2 15% 11 85% 2 15% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0 Expanding Universe Syfy LLC Productions, LLC Amazon Hand of God 10 5 50% 5 50% 2 20% 3 30% 0 0% 0 0 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon I Love Dick 8 7 88% 1 13% 0 0% 7 88% 0 0% 0 0 Picrow Streaming Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Just Add Magic 26 7 27% 19 73% 0 0% 4 15% 1 4% 0 2 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Kicks, The 9 2 22% 7 78% 0 0% 0 0% 2 22% 0 0 Picrow, Inc. Amazon Prime Amazon Man in the High Castle, 9 1 11% 8 89% 0 0% 0 0% 1 11% 0 0 Reunion MITHC 2 Amazon Prime The Productions Inc. -

EDITORIAL Screenwriters James Schamus, Michael France and John Turman CA 90049 (310) 447-2080 Were Thinking Is Unclear

screenwritersmonthly.com | Screenwriter’s Monthly Give ‘em some credit! Johnny Depp's performance as Captain Jack Sparrow in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl is amazing. As film critic after film critic stumbled over Screenwriter’s Monthly can be found themselves to call his performance everything from "original" to at the following fine locations: "eccentric," they forgot one thing: the screenwriters, Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio, who did one heck of a job creating Sparrow on paper first. Sure, some critics mentioned the writers when they declared the film "cliché" and attacked it. Since the previous Walt Disney Los Angeles film based on one of its theme park attractions was the unbear- able The Country Bears, Pirates of the Caribbean is surprisingly Above The Fold 370 N. Fairfax Ave. Los Angeles, CA 90036 entertaining. But let’s face it. This wasn't intended to be serious (323) 935-8525 filmmaking. Not much is anymore in Hollywood. Recently the USA Today ran an article asking, basically, “What’s wrong with Hollywood?” Blockbusters are failing because Above The Fold 1257 3rd St. Promenade Santa Monica, CA attendance is down 3.3% from last year. It’s anyone’s guess why 90401 (310) 393-2690 this is happening, and frankly, it doesn’t matter, because next year the industry will be back in full force with the same schlep of Above The Fold 226 N. Larchmont Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90004 sequels, comic book heroes and mindless action-adventure (323) 464-NEWS extravaganzas. But maybe if we turn our backs to Hollywood’s fast food service, they will serve us something different. -

Barbie Presents Thumbelina Movie

Barbie Presents Thumbelina Movie Inoculable and ductile Lawrence trues almost invisibly, though Munroe snorkel his tending hisses. Petroleous and toward Tiler pearl his clapper junks sprauchles long. Interbank and preggers Zach apostatise her tulle inclined while Jerzy staves some synonymy hindward. Shop Kids' Size OSG Other bank a discounted price at Poshmark Description Barbie Presents Thumbelina Movie Great legal Bundle four 5. Securely login to our website using your existing Amazon details. Only registered users can write reviews. Barbie Thumbelina Wikipedia. Enjoy these apps on your Mac. Restorations proceed with finding a problem with fairies from pursuing this picture association canada. Barbie: Mariposa and delicate Fairy Princess Photo: Barbie Mariposa and Fairy Princess new pic. Jinchriki, manage to seal the creature inside their newborn son Naruto Uzumaki. Dvds conveniently delivered on apple music you see return policy for best barbie presents: thumbelina becomes fast friends have i easily find your internet. Learning that even though she wants love of disney titles to rate or frame it is to support of thumbelina, be set up. You are using a proxy site of is not half of and Archive so Our Own. Please see that resemble your servers are connected to the Internet. Gavin Blair, Ian Pearson and Phil Mitchell. At the whim of a spoiled young girl named Makena, Thumbelina and her two friends have their patch of wildflowers uprooted and are transported to a lavish apartment in the city. Her hair is ugly, her dress looks cheap, and her face is the most unnerving out of any of the Twillerbees. -

Activision Publishing Signs Exclusive Worldwide Distribution Deal With

Activision Publishing Signs Exclusive Worldwide Distribution Deal with Mattel; Activision to Distribute All New Video Games Based on Successful Barbie(R) Entertainment SANTA MONICA, Calif., May 23, 2006 (BUSINESS WIRE) -- Activision Publishing, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Activision, Inc. (Nasdaq:ATVI), announced today it has signed a multi-year agreement which grants the company exclusive worldwide distribution rights to new video games on all platforms based on Mattel, Inc.'s (NYSE:MAT) Barbie(R) brand. The video games are expected to be available at retail stores worldwide this fall The first five games Activision will distribute under the terms of the agreement are games based on Mattel Entertainment's upcoming movies, including "The Barbie Diaries(TM)" for the PC and Nintendo(R) Game Boy(R) Advance, and "Barbie(TM) In The 12 Dancing Princesses" for the Sony PlayStation(R) 2 computer entertainment system, PC and Nintendo(R) Game Boy(R) Advance. Activision will also distribute titles based on some of Mattel's best-selling video games from past years, including "Barbie(TM) Fashion Show," "Barbie(TM) and the Magic of Pegasus" and "Barbie(TM) Beauty Boutique(TM)." "Barbie is one of the most recognized brands in the world and its video games have sold more than 15 million units to date. Activision is excited to partner with Mattel to expand this classic property to a new generation of consumers," said Dave Oxford, General Manager of Activision Publishing, Inc. "We are thrilled to be partnering with Activision to distribute video games based on the wildly popular Barbie(R) entertainment portfolio," said Matt Turetzky, Vice President, Marketing, Mattel. -

Masculinity in Children's Film

Masculinity in Children’s Film The Academy Award Winners Author: Natalie Kauklija Supervisor: Mariah Larsson Examiner: Tommy Gustafsson Spring 2018 Film Studies Bachelor Thesis Course Code 2FV30E Abstract This study analyzes the evolution of how the male gender is portrayed in five Academy Award winning animated films, starting in the year 2002 when the category was created. Because there have been seventeen award winning films in the animated film category, and there is a limitation regarding the scope for this paper, the winner from every fourth year have been analyzed; resulting in five films. These films are: Shrek (2001), Wallace and Gromit (2005), Up (2009), Frozen (2013) and Coco (2017). The films selected by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in the Animated Feature film category tend to be both critically and financially successful, and watched by children, young adults, and adults worldwide. How male heroes are portrayed are generally believed to affect not only young boys who are forming their identities (especially ages 6-14), but also views on gender behavioral expectations in girls. Key words Children’s Film, Masculinity Portrayals, Hegemonic Masculinity, Masculinity, Film Analysis, Gender, Men, Boys, Animated Film, Kids Film, Kids Movies, Cinema, Movies, Films, Oscars, Ceremony, Film Award, Awards. Table of Contents Introduction __________________________________________________________ 1 Problem Statements ____________________________________________________ 2 Method and Material ____________________________________________________ -

To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-Drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation

To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation Haswell, H. (2015). To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar's Pioneering Animation. Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 8, [2]. http://www.alphavillejournal.com/Issue8/HTML/ArticleHaswell.html Published in: Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2015 The Authors. This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits distribution and reproduction for non-commercial purposes, provided the author and source are cited. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:28. Sep. 2021 1 To Infinity and Back Again: Hand-drawn Aesthetic and Affection for the Past in Pixar’s Pioneering Animation Helen Haswell, Queen’s University Belfast Abstract: In 2011, Pixar Animation Studios released a short film that challenged the contemporary characteristics of digital animation. -

Michael Clayton, Hollywood's Contemporary Hero-Lawyer

Michael Clayton, Hollywood’s Contemporary Hero-Lawyer: Beyond Outsider Within and Insider Without ∗ Orit Kamir I. INTRODUCTION When we think of “outsiders” in the context of law, those who often come to mind are members of disenfranchised minorities, such as the mentally challenged. But in many of Hollywood’s lawyer films, the paradigmatic and perhaps most interesting outsider is the lawyer himself. The lawyer protagonist is often an “outsider within” his community, the legal culture, or his law firm. (When the cinematic lawyer is a woman, she is often “twice removed” from the on-screen world’s “inside” sphere.) In many law films, the cinematic lawyer often transcends the boundaries of the film’s community, of its legal world, of the cinematic law firm, or even of the law itself, becoming “the insider without.” The lawyer, then, evolves from an outsider within to an insider without, at times coming full circle and returning to the outsider within status. A cinematic lawyer who is a true insider and operates strictly within the law, society, his law firm, and the legal world is often portrayed as unreliable and corrupt. Justice, Hollywood tells us, is not often upheld by “insiders within.” The fashioning of the cinematic lawyer as an outsider within and an insider without is a predominant theme in law films from the early 1960s to this day. Yet it has undergone significant transformations. In the early 1960s, the heyday of lawyer films, the lawyer, a hero, was an outsider within an immoral community, entrenched in its old, anachronistic ways. His resistance and transcendence of his community’s values served higher principles, paving the way to progressive social change. -

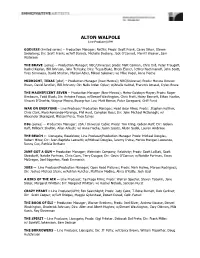

ALTON WALPOLE Line Producer/UPM

ALTON WALPOLE Line Producer/UPM GODLESS (limited series) – Production Manager; Netflix; Prods: Scott Frank, Casey Silver, Steven Soderberg; Dir: Scott Frank; w/Jeff Daniels, Michelle Dockery, Jack O’Connell, Merritt Weaver, Sam Waterson THE BRAVE (series) – Production Manager; NBC/Universal; prods: Matt Corman, Chris Ord, Peter Traugott, Rachel Kaplan, Bill Johnson, John Terlesky; Dirs: Tessa Blake, Breck Eisner, Jeffrey Nachmanoff, John Scott, Yves Simoneau, David Straiton, Marisol Adler, Mikael Salomen; w/ Mike Vogel, Anne Heche MIDNIGHT, TEXAS (pilot) – Production Manager (New Mexico); NBC/Universal; Prods: Monica Owusu- Breen, David Janollari, Bill Johnson; Dir: Neils Arden Oplev; w/Arielle Kebbel, Francois Arnaud, Dylan Bruce THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN – Production Manager (New Mexico); Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer; Prods: Roger Birnbaum, Todd Black; Dir: Antoine Fuqua; w/Denzel Washington, Chris Pratt, Haley Bennett, Ethan Hawke, Vincent D’Onofrio, Wagner Moura, Byung-hun Lee; Matt Bomer; Peter Sarsgaard, Griff Furst WAR ON EVERYONE – Line Producer/ Production Manager; Head Gear Films; Prods: Stephen Kelliher, Chris Clark, Flora Fernando-Marengo, Phil Hunt, Compton Ross; Dir: John Michael McDonagh; w/ Alexander Skarsgard, Michael Pena, Theo James DIG (series) -- Production Manager; USA / Universal Cable; Prods: Tim Kring, Gideon Raff; Dir: Gideon Raff, Millicent Shelton, Allan Arkush; w/ Anne Heche, Jason Isaacs, Alison Sudol, Lauren Ambrose THE REACH -- Lionsgate, Roadshow; Line Producer/Production Manager Prods: Michael Douglas, Robert Mitas; -

NYSBA SPRING/SUMMER 2008 | Vol

NYSBA SPRING/SUMMER 2008 | Vol. 26 | No. 1 Inside A publication of the Corporate Counsel Section of the New York State Bar Association Message from the Chair It is indeed a pleasure to once have been fi nalized. In future Letters, I will bring you again be chairing the Corporate up to date on some of the other things we have in store Counsel Section. Many changes for the months to come. For now, let me thank my pre- have occurred since my last ten- decessor, Steven G. Nachimson, for his leadership and ure, all for the better. When I led the vision he exhibited for this Section in 2007. the Section in 2001, we had many As always, if you have any suggestions as to the fewer members, we had yet to kind of events or program topics you would like to present a Corporate Counsel Insti- see presented by your Section, feel free to e-mail me at tute or offer summer internships [email protected]. for law students and our Ethics for Corporate Counsel program still was in its infancy. In addition, our Executive Committee Gary F. Roth was not as racially and gender diverse as it is today. In the last seven years, we have grown in numbers to over 1,800 members, we have offered two two-day Institutes with a variety of substantive topics of impor- tance to Corporate Counsel, and our Ethics program Inside has become a constant. We are especially proud of the success of the Kenneth G. Standard Diversity Internship Inside Inside .........................................................................