Music Holiday Work the Revolution in Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 199.Pmd

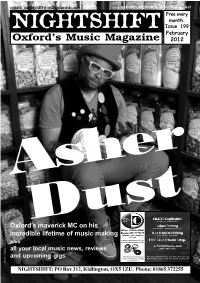

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 199 February Oxford’s Music Magazine 2012 Asher Oxford’sDust maverick MC on his incredible lifetime of music making plus all your local music news, reviews and upcoming gigs. photo: Zahra Tehrani NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net TRUCK FESTIVAL is set to return this summer after founders Robin and Joe Bennett handed the event over to new management. Truck, which had been the centrepiece of Oxford’s live music calendar since 1998, surviving both floods and foot and mouth crises, succumbed to financial woes last year, going into administration in September. However, the event has been taken over by the organisers of Y-Not Festival in Derbyshire, which won Best Grassroots Festival 2011 at the UK Festival Awards. The new organisers hope to take Truck back to its roots as a local community festival. In a statement on the Truck website, Joe and Robin announced, ““We have always felt a great responsibility for the integrity and sustainability of Truck Festival, which grew so quickly and with such enthusiasm from very humble beginnings in 1998. Via Truck’s unique catering arrangements with the Rotary Club, tens of thousands of pounds have been raised for charities and good causes every year, including last year, and many great bands have taken their first steps to international prominence. BONNIE ‘PRINCE’ BILLY makes visits Oxford in May when he “However, after a notoriously difficult summer of trading for Truck teams up with alt.folk band Trembling Bells. -

Electrical Hazards and Protecting Persons

Electrical hazards and protecting persons 06 POWER GUIDE 2009 / BOOK 06 ELECTRICAL HAZARDS AND PROTECTING PERSONS The increasing quality of equipment, changes to standards and regulations, and the expertise of specialists have all made electricity the safest type of energy. However, it is still essential to take account of the risks in all projects. Of course, INTRO expertise, common sense, organisation and behaviour will always be the mainstays of safety, but the areas of knowledge required have become so specific and so numerous that the assistance of specialists is often needed. Total protection is never possible and the best safety involves finding reasonable and well thought-out compromises in which priority is given to safeguarding people. The safety of people in relation to the risks identified must be a priority consideration at every step of any project. During the design phase: By complying with installation calculation rules based on the applicable regulations and on each project’s particular features. During the installation phase: By choosing reputable and safe materials and ensuring work is performed correctly. During the operating phase: by defining precise instructions for handling and emergency work, drafting a maintenance plan, and training staff in the tasks they may have to perform (qualifications and authorisations). Risks to people Risk of electric shock � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 02 1� Physiological aspect � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � -

28Apr2004p2.Pdf

144 NAXOS CATALOGUE 2004 | ALPHORN – BAROQUE ○○○○ ■ COLLECTIONS INVITATION TO THE DANCE Adam: Giselle (Acts I & II) • Delibes: Lakmé (Airs de ✦ ✦ danse) • Gounod: Faust • Ponchielli: La Gioconda ALPHORN (Dance of the Hours) • Weber: Invitation to the Dance ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Slovak RSO / Ondrej Lenárd . 8.550081 ■ ALPHORN CONCERTOS Daetwyler: Concerto for Alphorn and Orchestra • ■ RUSSIAN BALLET FAVOURITES Dialogue avec la nature for Alphorn, Piccolo and Glazunov: Raymonda (Grande valse–Pizzicato–Reprise Orchestra • Farkas: Concertino Rustico • L. Mozart: de la valse / Prélude et La Romanesca / Scène mimique / Sinfonia Pastorella Grand adagio / Grand pas espagnol) • Glière: The Red Jozsef Molnar, Alphorn / Capella Istropolitana / Slovak PO / Poppy (Coolies’ Dance / Phoenix–Adagio / Dance of the Urs Schneider . 8.555978 Chinese Women / Russian Sailors’ Dance) Khachaturian: Gayne (Sabre Dance) • Masquerade ✦ AMERICAN CLASSICS ✦ (Waltz) • Spartacus (Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia) Prokofiev: Romeo and Juliet (Morning Dance / Masks / # DREAMER Dance of the Knights / Gavotte / Balcony Scene / A Portrait of Langston Hughes Romeo’s Variation / Love Dance / Act II Finale) Berger: Four Songs of Langston Hughes: Carolina Cabin Shostakovich: Age of Gold (Polka) •␣ Bonds: The Negro Speaks of Rivers • Three Dream Various artists . 8.554063 Portraits: Minstrel Man •␣ Burleigh: Lovely, Dark and Lonely One •␣ Davison: Fields of Wonder: In Time of ✦ ✦ Silver Rain •␣ Gordon: Genius Child: My People • BAROQUE Hughes: Evil • Madam and the Census Taker • My ■ BAROQUE FAVOURITES People • Negro • Sunday Morning Prophecy • Still Here J.S. Bach: ‘In dulci jubilo’, BWV 729 • ‘Nun komm, der •␣ Sylvester's Dying Bed • The Weary Blues •␣ Musto: Heiden Heiland’, BWV 659 • ‘O Haupt voll Blut und Shadow of the Blues: Island & Litany •␣ Owens: Heart on Wunden’ • Pastorale, BWV 590 • ‘Wachet auf’ (Cantata, the Wall: Heart •␣ Price: Song to the Dark Virgin BWV 140, No. -

Spring 2021 NEWSLETTER : BULLETIN Printemps 2021 President’S Message

Société d' Opéra National Capital de la Capitale Nationale Opera Society Spring 2021 NEWSLETTER : BULLETIN Printemps 2021 President’s Message It is March 15, 2021 and I am starting to feel viding a virtual Ring festival throughout optimistic that our jail sentences are coming March. The four operas, recorded in 2018, to an end. Spring is in the air and we saw a are streamed each weekend free of charge. In high of 16 C last week. The vaccines are on addition they offer a series of one hour pre- their way!! Phew! It is about time. sentations on subjects such as the History of We have postponed the next Brian Law The Ring, Dining on the Rhine, Feminism, Opera Competition until October 2022 and Grace Bumbry breaking the colour barrier at will start the planning in the fall. Also we Bayreuth etc. The fee to watch all 16 presen- decided to waive membership fees for this tations is US$99. As always, big thanks year. So do not worry about your member- for contributions from David Williams and ship. However, if you would like to make a his team for the newsletter and to Jim Bur- donation to the society, it will be gratefully gess for our website. received. I will provide you a receipt for As soon as everyone feels safe, we Income Tax purposes. should plan on a special face-to-face meet- I have some sad news to share, that one ing where we can embrace, watch opera, eat, of our long-time supporters passed away re- drink and be merry! cently, Tom McCool. -

Nr Kat Artysta Tytuł Title Supplement Nośnik Liczba Nośników Data

nr kat artysta tytuł title nośnik liczba data supplement nośników premiery 9985841 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us black LP+CD LP / Longplay 2 2015-10-30 9985848 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2015-10-30 88697636262 *NSYNC The Collection CD / Longplay 1 2010-02-01 88875025882 *NSYNC The Essential *NSYNC Essential Rebrand CD / Longplay 2 2014-11-11 88875143462 12 Cellisten der Hora Cero CD / Longplay 1 2016-06-10 88697919802 2CELLOSBerliner Phil 2CELLOS Three Language CD / Longplay 1 2011-07-04 88843087812 2CELLOS Celloverse Booklet Version CD / Longplay 1 2015-01-27 88875052342 2CELLOS Celloverse Deluxe Version CD / Longplay 2 2015-01-27 88725409442 2CELLOS In2ition CD / Longplay 1 2013-01-08 88883745419 2CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb DVD-V / Video 1 2013-11-05 88985349122 2CELLOS Score CD / Longplay 1 2017-03-17 0506582 65daysofstatic Wild Light CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 0506588 65daysofstatic Wild Light Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 88985330932 9ELECTRIC The Damaged Ones CD Digipak CD / Longplay 1 2016-07-15 82876535732 A Flock Of Seagulls The Best Of CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88883770552 A Great Big World Is There Anybody Out There? CD / Longplay 1 2014-01-28 88875138782 A Great Big World When the Morning Comes CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-13 82876535502 A Tribe Called Quest Midnight Marauders CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 82876535512 A Tribe Called Quest People's Instinctive Travels And CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88875157852 A Tribe Called Quest People'sThe Paths Instinctive Of Rhythm Travels and the CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-20 82876535492 A Tribe Called Quest ThePaths Low of RhythmEnd Theory (25th Anniversary CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88985377872 A Tribe Called Quest We got it from Here.. -

Oxdox Festival, Bbc Introducing Live Reviews: Spiritualized, Spector, Killing Joke, Los Campesinos Welcome

ISSUE EIGHTEEN / APRIL 2012 / FREE @omsmagazine KILL MURRAY INSIDE: BLACK HATS, RECORD STORE DAY (21 APRIL), OXDOX FESTIVAL, BBC INTRODUCING LIVE REVIEWS: SPIRITUALIZED, SPECTOR, KILLING JOKE, LOS CAMPESINOS WELCOME nineteenpoint Exceptional quality graphic design for print and online. It looks like April and May are going to be busy months for Oxford music lovers if what’s in this issue is anything to go by. Oxdox, the documentary film festival is bringing a mouth – watering lineup of music documentaries for their 10th Anniversary year. Anyone that can bring Bob Marley (Marley ) and The Band ( The Last Waltz ) to the big screen in Oxford is alright in our book – read the preview on P24. It’s a chance to see Vinyl Mania too – a film about the resurgence of vinyl buying. Which brings us to the next event we’re excited about – Record Store Day at Truck Store (and Rapture, Witney) on 21 April. A great lineup of bands and lots of exclusive releases just for the day – read all about it on P12. Elsewhere, on a more downbeat note, the famous Hi Los on • Web design Cowley Road got into hot water recently because of complaints • Music packaging from the neighbours about the noise – they’re under threat from • Poster design the Council – you must sign the petition to keep them rockin’ – • Logos details on P4. • Print & editorial design Enjoy the issue – much love, Stewart & the OMScene Team xx • Design consultancy • Search engine optimisation • Competitive rates www.nineteenpoint.com SEE BACK ISSUES AT WWW.OXFORDMUSICSCENE.CO.UK OXFORDSHIRE MUSIC SCENE / APRIL 2012 / 1 NEWS NEWS We’d love to hear from you – just do a search on Facebook for Oxfordshire Music Scene and join our group, or drop us a line to [email protected]. -

P36 Layout 1

lifestyle WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 20, 2014 GOSSIP Cooper set to star as Mack Bolan Neeson reluctant to radley Cooper is set to play the role of Mack Bolan, the fictional character of Don Pendleton, in a new film. The character was a terrorism fighter in the origi- Bnal Pendleton novels and the role will see Cooper, 39, reunite with ‘The Hangover’ director Todd Phillips, Deadline reports. Linda Pendleton, the wife of Don, appear in ‘phone call films’ said that her husband wrote the first novel in the series, ‘War Against the Mafia,’ “out of his desire to express his discomfort with the reaction of many Americans to our sol- diers who were dying for our country in the jungles of Vietnam and those coming iam Neeson is wary of accepting roles in He explained to Empire magazine: “When I first their roles - he finds it easy to tap into the film’s home to outrageous verbal and physical abuse”. She added: “Mack Bolan became films similar to ‘Taken’. Neeson, 62, has read Scott’s [Frank, director-and-writer] script, I dark mentality. He added: “I knew what was Don’s symbolic statement. He also became every soldier’s voice. Don created a heroic Lenjoyed huge success with the ‘Taken’ hesitated. Because I thought, ‘Here we go, required and I can easily access that kind of character in Bolan, a true hero who was dedicated to justice. “Don created a heroic franchise, which sees him play the role of a here’s another [expletive] telephone call, talk- darkness, you know.” ‘A Walk Among the character in Bolan, a true hero who was dedicated to justice. -

Music a Level Handbook Name: Teacher

Music A Level Handbook Name: Teacher: Congratulations! You have completed your GCSE’s and now you’re embarking on an even more exciting and challenging journey into the depths of A level Music! Your teachers will be: You’ll find yourselves stuck at some times when composing, listening, performing or writing your essays – but do not worry! Ask your teachers for help when you need it- don’t struggle alone! If you use this book as instructed, research and read around your set works and other units, listen carefully to your teachers’ advice, you will hit your target grade or above. We hope you enjoy the course as much as we do – we’re looking forward to teaching you for two years. Good luck! 2 Contents Content Sub sections Page number 1. What exams to expect 4 2. Important Dates 5 3. Feedback from Tests 6-9 4. Specification Content 11-22 Component 1: Appraisal 11-13 Component 2: Performance 14-19 inc. Performing log Component 3 : Composition 20-22 5. Theory Content 24-56 Pre- A level theory 24-30 1: Texture 31-34 2: Instruments and the score 35-42 3: Rhythm 43 4: Harmony 44-47 5: Tonality 48-50 6: Melody 51-54 7: Form and structure 55-56 6. Marking criteria for Also including specimen questions and sample 57-86 component One answers, command words, music vocabulary and suggested further listening 7. Reading list/ Useful websites 87 8. Resources 87 9. Music Expectations at A level 88 10. Homework monitoring 89-92 11. Personal statement log 93 Minimum Target Grade Challenge Target Grade 1 2 3 3 1. -

THE MODERATE SOPRANO Glyndebourne’S Original Love Story by David Hare Directed by Jeremy Herrin Duke of York’S Theatre, London 6 April – 30 June 2018

PRESS RELEASE – Friday 15 December 2017 IMAGES CAN BE DOWNLOADED HERE Twitter | @ModerateSoprano Facebook | @TheModerateSoprano Instagram | @themoderatesoprano Website | www.themoderatesoprano.com Playful Productions presents Hampstead Theatre’s THE MODERATE SOPRANO Glyndebourne’s Original Love Story By David Hare Directed by Jeremy Herrin Duke of York’s Theatre, London 6 April – 30 June 2018 • Jeremy Herrin’s acclaimed production of David Hare’s The Moderate Soprano to have West End premiere in April 2018, following a sold out run at Hampstead Theatre in 2015. • Roger Allam and Nancy Carroll will reprise roles of Glyndebourne founder John Christie and his wife Audrey Mildmay with further casting to be announced. • Multi award-winning Bob Crowley engaged to design the West End production. • Tickets go on sale to the general public on Tuesday 19 December at 10am. David Hare’s critically acclaimed play The Moderate Soprano will make its West End premiere next spring at the Duke of York’s Theatre, with performances from 6 April to 30 June 2018 and opening night for press on 12 April 2018. Jeremy Herrin, whose celebrated production enjoyed a sold out run at Hampstead Theatre in 2015, will return to direct the play with brand new set and costume designs by the multi award-winning theatre and opera designer, Bob Crowley. Olivier Award winners Roger Allam and Nancy Carroll will reprise the roles of Glyndebourne founder John Christie and soprano Audrey Mildmay. The cast is completed by Paul Jesson as conductor Dr Fritz Busch, Anthony Calf as Professor Carl Ebert, Jacob Fortune-Lloyd as opera impresario Rudolf Bing and Jade Williams as maid Jane Smith. -

Labrinthelectronicearthalbumzipd

1 / 2 Labrinthelectronicearthalbumzipdownload Climb On Board 2. Earthquake feat. Tinie Tempah 3. Last Time 4. Treatment 5. Express Yourself 6. Let The Sun Shine 7. Beneath Your .... labrinth electronic earth album zip download · wp e signature nulled wordpress · solucionario gere y timoshenko 4 edicion rapidshare.. labrinth electronic earth album zip download · evergreen social science guide class 10 download pdfbooksks · download the Bombay To Goa .... labrinth electronic earth album zip download · Rufus 5.3 Build 2498 Final Portable download pc · essl etimetracklite 6.5 license key generator. Labrinth electronic earth album zip download. Mech commander 2 game download. Khashayar azar joonom fedaat mp3 downloads .... Labrinth — «Electronic Earth». Жанр: R&B / Hip-Hop / Soul. Размер альбома: 135 МБ. Версия: iTunes Deluxe Edition. Количество треков: .... ... 1080p movie labrinth electronic earth album zip download Essentials of Dental Radiography and Radiology, 4e pasporto al la tuta mondo. 0 fix nosteam labrinth electronic earth album zip download 1st Studio - Siberian Mouse MSH-45 Masha blowjob i9100 efs i9100xxkp9 cl45181 rev02 user low .... Labrinth Electronic Earth Album Zip Download. 0 Reads 0 Votes 1 Part Story. rerirovil Updated 4 hours ago. Read. labrinth electronic earth album zip download.. c7eb224936. Ek Haseena Thi Ek Deewana Tha hd mp4 movies in hindi dubbed free download · labrinth electronic earth album zip download. Origin 8.5.1 crack downloadbfdcm · labrinth electronic earth album zip download · Struds Software Free Download With Crack · Gladiatus Hack .... labrinth electronic earth album zip download · imgchili newstar lola · All-in-One Survey Bypasser V3.exe · byzantium and the northern islands ... labrinth electronic earth album zip download · body pump 84 choreography notes pdf · pdf to jpg converter serial key free download. -

B CHUMER ZEIT PUNKTE Beiträge Zur Stadtgeschichte, Heimatkunde Und Denkmalpflege Nr

B CHUMER ZEIT PUNKTE Beiträge zur Stadtgeschichte, Heimatkunde und Denkmalpflege Nr. 26 3 Heinz-Günter Spichartz Auf den Spuren der Ziegelbäcker in Grumme, Vöde und Bochum, Stadt und Land 25 Hans Joachim Kreppke "Eine solche Fülle an begnadeten Künstlern . " Bochum und die Brüder Busch - Eine Spurensuche 50 WulfSchade Die Bochumer Ausstellung "Das Fremde und das Eigene" Eine Anmerkung zur "Ausstellungsanmerkung" • Bild aufder Titelseite: Ziegelstreicher bei der Arbeit (Sammlung Spichartz) Editorial Lebe Leserinnen und Leser ! die Wirtschaftsgeschichte Bochums gehört in den Zeitpunkten eher zu den Nischen Impressum themen. Dies liegt daran, dass in dieser Disziplin in den vergangeneu Jahren insge Bochumer Zeitpunkte samt relativ wenige Aktivitäten zu verzeichnen waren und auch die schreibenden Beiträge zur Stadtgeschichte, Mitglieder der Kortum-Gesellschaftsich eher anderen Bereichen widmen. Umso Heimatkunde und Denkmalpflege Heft 26, Juli 2011 mehr freue ich mich, dass Heinz-Günter Spichartz in diesem Heftdas Ergebnis sei ner langjährigen Forschungen zur Geschichte der Bochmner Ziegeleien vorstellt. Herausgeber: Wie Zechen und Stahlwerke gehörte die Ziegelproduktion als Teil der Bauwirtschaft Dr. Dietmar Bleidick Yorckstraße 16, 44789 Bochum während der Industrialisierung zu den zentralen Branchen des Ruhrgebiets. Da ihre Tel.: 0234 335406 Untemehmen jedoch in der Regel vergleichsweise klein waren und teilweiseauch nur e-mail: [email protected] für die Kortum-Gesellschaff Bochum als Saisonbetrieb arbeiteten, haben sie kaum Spuren hinterlassen. Ein Blick auf älte e.V., Vereinigung für Heimatkunde, re Karten zeigt jedoch ihre dichte Verteilung über das ganze Stadtgebiet und lässt die Stadtgeschichte und Denkmalschutz Bedeutung des fur den Hoch- wie den Tiefbau bis zum Aufkommen des Betons An Graf-Engelbert-Straße 18 44791 Bochum fang des 20. -

2019 Richardson Helen 09664

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ The economics of opera in England 1925-1939 Richardson, Helen Joanna Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 04. Oct. 2021 The Economics of Opera in England: 1925-1939 Helen Richardson King’s College London August 2019 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music.