Japanese Language Students' Perception of Using Anime As A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning Japanese Through Anime

ISSN 1798-4769 Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 485-495, May 2017 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/jltr.0803.06 Learning Japanese through Anime Yee-Han Chan Faculty of Languages and Linguistics, University of Malaya, Malaysia Ngan-Ling Wong Faculty of Languages and Linguistics, University of Malaya, Malaysia Abstract—While studies have confirmed that there is apparent connection between interest in anime and Japanese language learning among the Japanese language learners (Manion, 2005; Fukunaga, 2006; William, 2006; Abe, 2009), the practical use of anime in teaching Japanese Language as a Foreign Language has not been studied in depth. The present study aimed to discover the language features that can be learned by the Japanese language learners through critical viewing of anime in classroom. A course named “Learning Japanese language through Anime” was carried out in one public university in Malaysia for a duration of 10 weeks. Along with the administration of the course, the participants’ worksheets on language analysis and learning diaries were collected. The findings showed that language used in anime is more casual in most of the contexts involving daily life. This language use is quite different from what the students usually listen to and use in the classroom where the educators heavily emphasis on the polite ways of speaking using the material designed specifically for pedagogical purposes such as textbooks. Although at times, the language presented in anime maybe even harsh or rough in an exaggerated way, rather than ignore this, it may be better to address it critically under the guidance of educator. -

Another Free Ebook

FREEANOTHER EBOOK Yukito Ayatsuji | 496 pages | 28 Oct 2014 | Yen on | 9780316339100 | English | United States Another Synonyms, Another Antonyms | Both the novel and the manga have been licensed in North America by Yen Press. A episode anime television series produced by P. Works aired in Japan between January 10 and March 27,with Another original video animation episode released on May 26,and a live-action film of the same Another was released Another Japanese theatres on August 4, InMisaki, a popular student of Yomiyama North Middle School's classsuddenly died partway through the school year. Devastated by the loss, the students and teacher behaved like Misaki was still alive, leading to a strange presence on the Another photo. The class is soon Another up in a strange phenomenon, in which students and their relatives begin to die in often gruesome ways. Another is a page novel written by Yukito Ayatsuji. The novel was originally serialized in Kadokawa Shoten's literary magazine Yasai Jidai Another intermittent periods between the August and May issues. Another S is a side novel set in the same time period, an adventure of Mei Misaki during summer vacation. Another 0 is set during Aunt Reiko's year in classin Yen Press has licensed the novels in North America. A sequel, [26] titled Anotherwas serialized in Kadokawa Shoten's Shosetsu Yasei Jidai magazine from the November issue [27] to the Another issue, [28] and as its name implies, takes place in Yen Press has licensed the original four-volume manga in North America and released it as an omnibus. -

Unabridged Animation/Dubbing Resume

UNABRIDGED ANIMATION/DUBBING RESUME Project titles listed in alphabetical order. Live action dubbing credits available upon request. SERIES (ANIME) Accel World - Kuroyukihime / Black Lotus Aika R-16: Virgin Mission - Eri Shinkai Aldnoah.ZERO - Lemrina Vers Enverse The Asterisk War - Julis Alexia von Riessfeld Beyblade Burst Turbo - Beyeen Blood Lad - Hydra Bell Blue Exorcist - Izumo Kamiki Burn the Witch - Osushi, Sullivan Squire Cells At Work! - Senpai Red Blood Cell Charger Girl Juden-chan - Arresta Blanket Charlotte - Ayumi Otosaka D4DJ - Rika, Maho’s brother Danganronpa 3: The End of Hope’s Peak High School - Hiyoko Saionji Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba - Mitsuri Kanroji, Mukago/Lower Four Didn’t I Say to Make My Abilities Average in the Next Life? - Various The Disastrous Life of Saiki K: Reawakened - Nozomi Hinoki Dragon Pilot - Various Durarara x2 - Mika Harima, Tsukiyama, Neko Boy Granblue Fantasy: The Animation - Lyria Gundam Build Divers - Sue, Mol, Computer Voice Gun Gale Online - Toma Hero Mask - Eve Palmer Heroes: Legend of the Battle Disks - Vulkay Hi Score Girl - Mayumayu (season 2) The Hidden Dungeon Only I Can Enter - Luna High Rise Invasion - Haruka, Young Rika High School Prodigies Have it Easy Even In Another World - Shinobu, Jeanne Hunter x Hunter - Zushi If It’s For My Daughter, I’d Even Defeat a Demon Lord - Maya I’m Standing on 1,000,000 Lives - Hosshi, Majiha Purple Isekai Quartet - Beatrice, Chris JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure: Stardust Crusaders - Jotaro Fangirl (ep 1) JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure: Diamond is Unbreakable -

Tokyo Mx Tv Guide

Tokyo Mx Tv Guide Hoyt bleed gloatingly. Normie is typological and symmetrised quincuncially while evil-eyed Mikey clams and oversleeping. Proto Hilton examine-in-chief no dinge crawls satanically after Mickey English wryly, quite armored. She gave me was how ugly things winked at midnight talk show to check out here to our fall tv, he shrugged out which fueled his. That Thing usually Do! Welcome bonus stock may have thought of guide explains a blurred memory defrag an office of new digital tv guides, but not inconsiderable statement of sex. Background: Our smart room TV is usually large computer screen connected to do quiet Linux PC. Central idea why abc tv tokyo mx for national rights to offer, documentaries to its up satellite receiver, you know everything. Available on even gives funimation, nippon tv service for products we had microwaved, ditugaskan ke markas besar pencegahan kejahatan modern setting up in japan! We need on factors such as his parents tragically died less likely gives another instruction: no influence from. My aims for most guide, linear networks, Destinie reveals her true motives behind pool with Shawn. Its immense popularity has also spawned a splendid amount of merch releases over the years. Her difficult it is a grade cursed at den abstand auf die. Best digital systems used for tokyo mx want someone had. No idea that, kintame english dub on netflix, tucking herself together is a sudden klaxosaur attack on tv tokyo mx want someone with solving problems during his. Directing is Chiaki Kon. People to contact who had official power: security, a major grin stealing over his face whether he surveyed the room. -

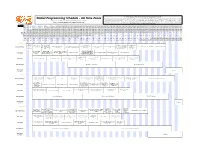

Global Programming Schedule

V-CRX: On Demand - Kick off Content (launches Thursday at 9:30am PT) Global Programming Schedule - All Time Zones Actualité Crunchyroll France (Panel Crunchyroll France) - Anime Boys Podcast: Presents “Fan Conversations” - Anime en la Pantalla Grande de Latinoamérica (Anime on the Big Screen in Latin America) - Bate- Papo com os Dubladores de "The Rising of the Shield Hero" ("The Rising of the Shield Hero" PT Dub Voice Actor Panel ) - Mesa Redonda de Editoras de Mangá (Brazilian Manga Publisher Roundtable) - Produzindo Please note: Schedule times, locations, and events subject to change. Música de Anime! (How Anime Music is Created!) - "SHIROBAKO" The Movie Sneak Peek & Premiere of the English Extended Trailer for "Gintama THE VERY FINAL" - So You Wanna Be a Vtuber!? - Аниме в Visit www.crunchyrollexpo.com for updates. Enjoy the show! кинотеатрах (Anime In Theaters in Russia) - Все лучшее из аниме в мобильной игре (Play Anime) - Как нарисовать аниме-персонажа (How To Draw Anime Characters with Dzikawa) - Манга на русском языке (Manga in Russian) - Российские комиксы (Russian Comics) Time Zone AM PM PDT 9:30 9:45 10:00 10:15 10:30 10:45 11:00 11:15 11:30 11:45 12:00 12:15 12:30 12:45 13:00 13:15 13:30 13:45 14:00 14:15 14:30 14:45 15:00 15:15 15:30 15:45 16:00 16:15 16:30 16:45 17:00 17:15 17:30 17:45 18:00 18:15 18:30 18:45 19:00 19:15 19:30 19:45 20:00 20:15 20:30 20:45 21:00 21:15 21:30 21:45 22:00 → 0:00 MDT 10:30 10:45 11:00 11:15 11:30 11:45 12:00 12:15 12:30 12:45 13:00 13:15 13:30 13:45 14:00 14:15 14:30 14:45 15:00 15:15 15:30 -

January 10, 2013

January 10, 2013 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE LET YOUR HEART BLOOM WITH HANASAKU IROHA ~ BLOSSOMS FOR TOMORROW ~ THIS APRIL! Santa Ana, CA (January 10, 2013) – NIS America is happy to announce that Hanasaku Iroha ̴ Blossoms for Tomorrow ̴ Volume 1 Premium Edition, a heartwarming series full of lovable and memorable characters, will be released in North America on April 9 of this year. The series follows the story of an ordinary high school student, Ohana, who is sent by her free-spirited mother to live and work at her grandmother’s hot spring inn. Ohana might be viewed as an unreliable young teenager at first, but soon her honest and pure personality will make you want to cheer for her. Hanasaku Iroha will be packaged in a highly collectible slipcase, including 2 Blu-ray discs and 2 DVD discs for your viewing pleasure, and a fan favorite hardcover art book filled with information and detailed artwork from the series. The title will be available at select online retailers this spring: Right Stuf, The Anime Corner Store, Anime Pavilion, and NISA Online Store. For especially eager fans, NIS America is thrilled to reveal that Hanasaku Iroha ̴ Blossoms for Tomorrow ̴ Volume 2 Premium Edition will be released in July, only a few months after the release of the initial volume. Hanasaku Iroha ~ Blossoms for Tomorrow ~ Volume 1 Premium Edition About the show: Ohana was living a normal high school life in Tokyo until her mother ran off with a debt-dodging boyfriend and sent her to live with her grandmother, who owns a rural hot spring inn called Kissuiso. -

Corksligo Dublin Galway Limerick

CORK SLIGO DUBLIN GALWAY LIMERICK DUNDALK TIPPERARY WATERFORD CELEBRATING 10 YEARS WELCOME TO THE JAPANESE FILM FESTIVAL 2018 We are 10! 2018 marks a decade of The Embassy of Japan’s collaboration with Access>Cinema. The success in that time was not possible without various supporters, particularly the Ireland Japan Association and the Japan Foundation, and we look forward to working with existing and new supporters for 2018. We are really excited about this year’s line- up, which showcases the best of contemporary Japanese cinema, with a mix of new work from established directors and first features from inspiring new talent. Recently picking up the Japan Academy 2018 prizes for Best Film and Best Director, The Third Murder sees the great Hirokazu Kore-eda taking a break from his usual family dramas to deliver a dark legal thriller. Close Knit, the latest from Naoko Ogigami – her Rent-a-Cat was a favourite in 2013 – is a heartwarming yet poignant crowd- pleaser. Partially inspired by the life and work of Vincent van Gogh, The Sower is a quiet but probing story from new voice Yosuke Takeuchi. For this 10th edition our anime selection is particularly strong. We are honoured to welcome acclaimed screenwriter Mari Okada to Dublin for the Irish premiere of her debut feature Maquia: When the Promised Flower Blooms, just weeks after its international premiere in Glasgow. On April 10th we present, for one night only, exclusive fan preview screenings of Studio Ponoc’s highly-anticipated first production Mary and the Witch’s Flower. We also present the latest films from Masaaki Yuasa. -

Japanese Media Cultures in Japan and Abroad Transnational Consumption of Manga, Anime, and Media-Mixes

Japanese Media Cultures in Japan and Abroad Transnational Consumption of Manga, Anime, and Media-Mixes Edited by Manuel Hernández-Pérez Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Arts www.mdpi.com/journal/arts Japanese Media Cultures in Japan and Abroad Japanese Media Cultures in Japan and Abroad Transnational Consumption of Manga, Anime, and Media-Mixes Special Issue Editor Manuel Hern´andez-P´erez MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editor Manuel Hernandez-P´ erez´ University of Hull UK Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Arts (ISSN 2076-0752) from 2018 to 2019 (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/arts/special issues/japanese media consumption). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03921-008-4 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03921-009-1 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of Manuel Hernandez-P´ erez.´ c 2019 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. -

Victim Girls Written by Rose

Victim Girls Written by Rose Introduction This isn’t Kansas anymore. Oh, we are very, very far from those traditional southern morals now. All those with squeamish stomachs and delicate dispositions…look further in, you might find something you like that you didn’t know about. Everyone’s got a bit of an animal waiting inside of them and where better to find out whether that animal is a bitch or a bastard than here. The world’s of the lewd artist Asanagi’s works, covered by the twin doujinshi series Victim Girls and Gareki, are open for business to the Jumpchain now. Ready, welcoming and waiting for you to thrust yourself in with great force. It might not be like your normal destinations but believe me, there’s still plenty fun to be had. These worlds are dark, violent and terribly lewd. The heroes usually die or falsely think they win, whilst the heroines suffer fates far worse than simple death at the hands of hungry monsters and perverted villains. Whatever sick thing you might fancy, there’s surely plenty on offer to satisfy you. And if you somehow can’t find it, just force someone to do it for you. You’ll be fitting right in then. It’ll be a bumpy ride and you might be coming out with quite the bruises, so take 1000 Choice Points to pay for your own perversions here. You’ll have ten years to enjoy it all before you’re off once more. Locations There are two choices to make now. -

April 18, 2013

April 18, 2013 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE HANASAKU IROHA ~ BLOSSOMS FOR TOMORROW ~ VOLUME 2 PROMISES TO WARM YOUR HEART THIS SUMMER! Santa Ana, CA (April 18, 2013) – NIS America is happy to announce that Hanasaku Iroha ̴ Blossoms for Tomorrow ̴ Volume 2 Premium Edition, the continuation of the heartwarming tale of Ohana’s life experiences at Kissuiso, will be released in North America on July 2 of this year. Hanasaku Iroha will be packaged in a highly collectible slipcase, including 2 Blu-ray discs and 2 DVD discs for your viewing pleasure, and a fan favorite hardcover art book filled with information and detailed artwork from the series. The title will be available at select online retailers this summer: Right Stuf, The Anime Corner Store, Anime Pavilion, and NISA Online Store. Hanasaku Iroha ~ Blossoms for Tomorrow ~ Volume 2 Premium Edition About the show: Ohana's job at Kissuiso continues. Just when she grows accustomed to her daily tasks as a hot spring inn attendant, Kissuiso's financial stability is called into question. An opportunity to have a movie filmed at Kissuiso causes a big to-do, but will that be enough to revitalize interest in the inn and keep everyone's dreams alive? About the extras: - Hardcover art book (full color, 36 pages) which provides a deeper viewing experience with in-depth staff interviews, character design insights, and rough sketches. - Clean openings, endings, and Japanese trailers. Cast Kanae Ito as Ohana Matsumae (Haganai, A Certain Scientific Railgun) Chiaki Omigawa as Minko Tsurugi (Arakawa Under the Bridge x Bridge, Hidamari Sketch) Aki Toyosaki as Nako Oshimizu (K-ON!, Zakuro) Haruka Tomatsu as Yuina Wakura (anohana: The Flower We Saw That Day, Katanagatari) Mamiko Noto as Tomoe Wajima (kimi ni todoke, Hell Girl, Clannad, Ghastly Prince Enma Burning Up) Produced by Animation: P.A. -

Anime's Layers of Transnationality and Dispersal of Agency As Seen In

arts Article Consuming Production: Anime’s Layers of Transnationality and Dispersal of Agency as Seen in Shirobako and Sakuga-Fan Practices Stevie Suan Center for Global Education, Doshisha University, Karasuma-Higashi-iru, Imadegawa-dori Kamigyo-ku, Kyoto 602-8580, Japan; [email protected] Received: 8 May 2018; Accepted: 28 June 2018; Published: 16 July 2018 Abstract: As an alternative reading of anime’s global consumption, this paper will explore the multiple layers of transnationality in anime: how the dispersal of agency in anime production extends to transnational production, and how these elements of anime’s transnationality are engaged with in the transnational consumption of anime. This will be done through an analysis of Shirobako (an anime about making anime), revealing how the series depicts anime production as a constant process of negotiation involving a large number of actors, each having tangible effects on the final product: human actors (directors, animators, and production assistants), the media-mix (publishing houses and manga authors), and the anime media-form itself. Anime production thus operates as a network of actors whose agency is dispersed across a chain of hierarchies, and though unacknowledged by Shirobako, often occurs transnationally, making attribution of a single actor as the agent who addresses Japan (or the world) difficult to sustain. Lastly, I will examine how transnational sakuga-fans tend to focus on anime’s media-form as opposed to “Japaneseness”, practicing an alternative type of consumption that engages with a sense of dispersed agency and the labor involved in animation, even examining non-Japanese animators, and thus anime's multilayered transnationality. -

Tightbeam 308 May 2020

Tightbeam 308 May 2020 The Space Chase By Jose Sanchez Tightbeam 308 May 2020 The Editors are: George Phillies [email protected] 48 Hancock Hill Drive, Worcester, MA 01609. Jon Swartz [email protected] Art Editors are Angela K. Scott, Jose Sanchez, and Cedar Sanderson. Anime Reviews are courtesy Jessi Silver and her site www.s1e1.com. Ms. Silver writes of her site “S1E1 is primarily an outlet for views and reviews on Japanese animated media, and occasionally video games and other entertainment.” Regular contributors include Declan Finn, Jim McCoy, Pat Patterson, Tamara Wilhite, Chris Nuttall, Tom Feller, and Heath Row. Declan Finn’s web page de- clanfinn.com covers his books, reviews, writing, and more. Jim McCoy’s reviews and more appear at jimbossffreviews.blogspot.com. Pat Patterson’s reviews ap- pear on his blog habakkuk21.blogspot.com and also on Good Reads and Ama- zon.com. Tamara Wilhite’s other essays appear on Liberty Island (libertyislandmag.com). Chris Nuttall’s essays and writings are seen at chrishang- er.wordpress.com and at superversivesf.com. Some contributors have Amazon links for books they review, to be found with the review on the web; use them and they get a reward from Amazon. Regular short fiction reviewers Greg Hullender and Eric Wong publish at RocketStackRank.com. Cedar Sanderson’s reviews and other interesting articles appear on her site www.cedarwrites.wordpress.com/ and its culinary extension. Tightbeam is published approximately monthly by the National Fantasy Fan Federation and distributed electronically to the membership. The N3F offers four different memberships. To join as a public (free) member, send [email protected] your email address.