Cooperation Between Anime Producers and the Japan Self-Defense Force : Creating Fantasy And/Or Propaganda?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 2015 Seven Seas.Indd

SEVEN SEAS Monster Musume, vol. 6 Story & Art by OKAYADO A New York Times manga bestseller Monster Musume is an ongoing manga series that presents the classic harem comedy with a fantastical twist: the female cast of characters that tempts our male hero is comprised of exotic and enticing supernatural creatures like lamias, centaurs, and harpies! Monster Musume will appeal to fans of supernatural comedies like Inukami! and harem comedies like Love Hina. Each volume is lavishly illustrated and includes a color insert. hat do world governments do when they learn that Wfantastical beings are not merely fiction, but flesh and blood —not to mention feather, hoof, and fang? Why, they create new regulations, of course! “The Interspecies Cultural Exchange Accord” ensures that these once-mythical creatures assimilate (cover in development) into human society...or else! MARKETING PLANS: When hapless human twenty-something Kurusu Kimihito becomes • Promotion at Seven Seas an involuntary “volunteer” in the government homestay program website gomanga.com for monster girls, his world is turned upside down. A reptilian lamia • Promotion on twitter.com/ named Miia is sent to live with him, and it is Kimihito’s job to tend gomanga and facebook. to her every need and make sure she integrates into his everyday com/gomanga life. While cold-blooded Miia is so sexy she makes Kimihito’s blood ALSO AVAILABLE: boil with desire, the penalties for interspecies breeding are dire. Monster Musume, vol. 5 (11/14) ISBN: 978-1-626921-06-1 Even worse, when a buxom centaur girl named Centorea and $12.99 ($14.99 CAN) a scantily clad harpy named Papi move into Kimihito’s house, what’s a full-blooded young man with raging hormones to do?! Monster Musume, vol. -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

11Eyes Achannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air

11eyes AChannel Accel World Acchi Kocchi Ah! My Goddess Air Gear Air Master Amaenaideyo Angel Beats Angelic Layer Another Ao No Exorcist Appleseed XIII Aquarion Arakawa Under The Bridge Argento Soma Asobi no Iku yo Astarotte no Omocha Asu no Yoichi Asura Cryin' B Gata H Kei Baka to Test Bakemonogatari (and sequels) Baki the Grappler Bakugan Bamboo Blade Banner of Stars Basquash BASToF Syndrome Battle Girls: Time Paradox Beelzebub BenTo Betterman Big O Binbougami ga Black Blood Brothers Black Cat Black Lagoon Blassreiter Blood Lad Blood+ Bludgeoning Angel Dokurochan Blue Drop Bobobo Boku wa Tomodachi Sukunai Brave 10 Btooom Burst Angel Busou Renkin Busou Shinki C3 Campione Cardfight Vanguard Casshern Sins Cat Girl Nuku Nuku Chaos;Head Chobits Chrome Shelled Regios Chuunibyou demo Koi ga Shitai Clannad Claymore Code Geass Cowboy Bebop Coyote Ragtime Show Cuticle Tantei Inaba DFrag Dakara Boku wa, H ga Dekinai Dan Doh Dance in the Vampire Bund Danganronpa Danshi Koukousei no Nichijou Daphne in the Brilliant Blue Darker Than Black Date A Live Deadman Wonderland DearS Death Note Dennou Coil Denpa Onna to Seishun Otoko Densetsu no Yuusha no Densetsu Desert Punk Detroit Metal City Devil May Cry Devil Survivor 2 Diabolik Lovers Disgaea Dna2 Dokkoida Dog Days Dororon EnmaKun Meeramera Ebiten Eden of the East Elemental Gelade Elfen Lied Eureka 7 Eureka 7 AO Excel Saga Eyeshield 21 Fight Ippatsu! JuudenChan Fooly Cooly Fruits Basket Full Metal Alchemist Full Metal Panic Futari Milky Holmes GaRei Zero Gatchaman Crowds Genshiken Getbackers Ghost -

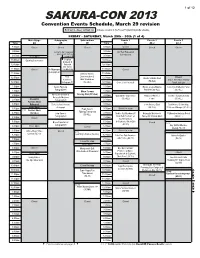

Sakura-Con 2013

1 of 12 SAKURA-CON 2013 Convention Events Schedule, March 29 revision FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (2 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (3 of 4) FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (4 of 4) Panels 4 Panels 5 Panels 6 Panels 7 Panels 8 Workshop Karaoke Youth Console Gaming Arcade/Rock Theater 1 Theater 2 Theater 3 FUNimation Theater Anime Music Video Seattle Go Mahjong Miniatures Gaming Roleplaying Gaming Collectible Card Gaming Bold text in a heavy outlined box indicates revisions to the Pocket Programming Guide schedule. 4C-4 401 4C-1 Time 3AB 206 309 307-308 Time Time Matsuri: 310 606-609 Band: 6B 616-617 Time 615 620 618-619 Theater: 6A Center: 305 306 613 Time 604 612 Time Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed 7:00am Closed Closed 7:00am FRIDAY - SATURDAY, March 29th - 30th (1 of 4) 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am 7:30am Main Stage Autographs Sakuradome Panels 1 Panels 2 Panels 3 Time 4A 4B 6E Time 6C 4C-2 4C-3 8:00am 8:00am 8:00am Swasey/Mignogna showcase: 8:00am The IDOLM@STER 1-4 Moyashimon 1-4 One Piece 237-248 8:00am 8:00am TO Film Collection: Elliptical 8:30am 8:30am Closed 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am 8:30am (SC-10, sub) (SC-13, sub) (SC-10, dub) 8:30am 8:30am Closed Closed Closed Closed Closed Orbit & Symbiotic Planet (SC-13, dub) 9:00am Located in the Contestants’ 9:00am A/V Tech Rehearsal 9:00am Open 9:00am 9:00am 9:00am AMV Showcase 9:00am 9:00am Green Room, right rear 9:30am 9:30am for Premieres -

The Formation of Temporary Communities in Anime Fandom: a Story of Bottom-Up Globalization ______

THE FORMATION OF TEMPORARY COMMUNITIES IN ANIME FANDOM: A STORY OF BOTTOM-UP GLOBALIZATION ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Geography ____________________________________ By Cynthia R. Davis Thesis Committee Approval: Mark Drayse, Department of Geography & the Environment, Chair Jonathan Taylor, Department of Geography & the Environment Zia Salim, Department of Geography & the Environment Summer, 2017 ABSTRACT Japanese animation, commonly referred to as anime, has earned a strong foothold in the American entertainment industry over the last few decades. Anime is known by many to be a more mature option for animation fans since Western animation has typically been sanitized to be “kid-friendly.” This thesis explores how this came to be, by exploring the following questions: (1) What were the differences in the development and perception of the animation industries in Japan and the United States? (2) Why/how did people in the United States take such interest in anime? (3) What is the role of anime conventions within the anime fandom community, both historically and in the present? These questions were answered with a mix of historical research, mapping, and interviews that were conducted in 2015 at Anime Expo, North America’s largest anime convention. This thesis concludes that anime would not have succeeded as it has in the United States without the heavy involvement of domestic animation fans. Fans created networks, clubs, and conventions that allowed for the exchange of information on anime, before Japanese companies started to officially release anime titles for distribution in the United States. -

Girls Und Panzer by Sjchan and Ancillaanon V.1.0 “The Ministry of Education Has Ordered

Girls und Panzer By SJChan and AncillaAnon V.1.0 “The Ministry of Education has ordered high schools and universities to strengthen Panzerfahren education.” This is a world very much like the one you’re used to, Earth, Cradle of Humanity. The year is… unspecified, but probably sometime in the mid to late 21st century. World War II played out as it usually does on these worlds, with one minor change. Tanks were never able to be quite as large as they are in most other worlds, and so, young women were selected to crew these weapons of war. Now, more than a century after the end of the war, this seemingly minor change has resulted in a subtly different world. First off, in the world of Girls und Panzer (the English word for young women and the German word for Tank), Tankery, also known as Senshado in Japanese or Panzerfahren in German, is the most popular sport / martial art. It is practiced exclusively by girls and women. Tankery is an all ages activity, with Grade School teams, Junior High Teams, High School Teams, College Teams, and even corporate and professional Teams. Second, and even stranger, is the fact that all schools have been moved off of dryland and onto the decks of gargantuan Schoolships, most of which are based off of Aircraft Carriers, but scaled dramatically upward. The Schoolship Zuikaku, home to Ooarai Girls Academy, is 7.6 kilometers long and 1.1 kilometers at its widest. At its highest, the stupendous vessel tops out at 906 meters from the bottom of the ship to the top of its tower, and it has a draft of 250 meters… and Schoolships like HMS Ark Royal and Kiev dwarf Zuikaku. -

Japanese Animation Guide: the History of Robot Anime

Commissioned by Japan's Agency for Cultural Affairs Manga, Animation, Games, and Media Art Information Bureau Japanese Animation Guide: The History of Robot Anime Compiled by Mori Building Co., Ltd. 2013 Commissioned by Japan's Agency for Cultural Affairs Manga, Animation, Games, and Media Art Information Bureau Japanese Animation Guide: The History of Robot Anime Compiled by Mori Building Co., Ltd. 2013 Addition to the Release of this Report This report on robot anime was prepared based on information available through 2012, and at that time, with the exception of a handful of long-running series (Gundam, Macross, Evangelion, etc.) and some kiddie fare, no original new robot anime shows debuted at all. But as of today that situation has changed, and so I feel the need to add two points to this document. At the start of the anime season in April of 2013, three all-new robot anime series debuted. These were Production I.G.'s “Gargantia on the Verdurous Planet," Sunrise's “Valvrave the Liberator," and Dogakobo and Orange's “Majestic Prince of the Galactic Fleet." Each was broadcast in a late-night timeslot and succeeded in building fanbases. The second new development is the debut of the director Guillermo Del Toro's film “Pacific Rim," which was released in Japan on August 9, 2013. The plot involves humanity using giant robots controlled by human pilots to defend Earth’s cities from gigantic “kaiju.” At the end of the credits, the director dedicates the film to the memory of “monster masters” Ishiro Honda (who oversaw many of the “Godzilla” films) and Ray Harryhausen (who pioneered stop-motion animation techniques.) The film clearly took a great deal of inspiration from Japanese robot anime shows. -

Collaborative Creativity, Dark Energy, and Anime's Global Success

Collaborative Creativity, Dark Energy, and Anime’s Global Success ◆特集*招待論文◆ Collaborative Creativity, Dark Energy, and Anime’s Global Success 協調的創造性、ダーク・エナジー、アニメの グローバルな成功 Ian Condry Associate Professor, Comparative Media Studies, Massachusetts Institute of Technology コンドリー・イアン マサチューセッツ工科大学比較メディア研究准教授 In this essay, I give an overview of some of the main ideas of my new book The Soul of Anime: Collaborative Creativity and Japan’s Media Success Story. Drawing on ethnographic research, including fieldwork at Madhouse, as well as a historical consideration of the original Gundam series, I discuss how anime can be best understood in terms of platforms for collaborative creativity. I argue that the global success of Japanese animation has grown out of a collective social energy that operates across industries—including those that produce film, television, manga (comic books), and toys and other licensed merchandise—and connects fans to the creators of anime. For me, this collective social energy is the soul of anime. 本論文において、拙著『アニメのダーク・エナジー:協調的創造性と日本のメディアの成功例』 における中心的なアイデアの紹介を行う。アニメを制作する企業マッドハウスにおけるフィール ドワークを含む、人類学的な研究を行うとともに、オリジナルの『ガンダム』シリーズに関する 歴史的な考察をふまえて、協調的創造性のプラットフォームとしてアニメを位置付けることがで きるかどうか検討する。日本アニメのグローバルな成功は、映画、テレビ、漫画、玩具、そして その他のライセンス事業を含めて、アニメファンと創作者をつなぐ集団的なソーシャル・エナジー に基づいていると主張する。このような集団的なソーシャル・エナジーがアニメの精神であると 著者は考えている。 Keywords: Media, Popular Culture, Globalization, Japan, Ethnography Acknowledgements: Thank you to Motohiro Tsuchiya for including me in this project. I think “Platform Lab” is an excellent rubric because I believe media should be viewed as a platform of participation rather than content for consumption. I view scholarship the same way. My anime research was supported by the Japan Foundation, the US National Science Foundation, and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. I have also received generous funding from, MIT, Harvard, Yale, and the Fulbright program. -

Aniplex of America Launches Teaser Site for Café Comedy BLEND-S and Announces Special Café Collaboration Event in Los Angeles

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 11, 2017 Aniplex of America Launches Teaser Site for Café Comedy BLEND-S and Announces Special Café Collaboration Event in Los Angeles © MIYUKI NAKAYAMA, HOUBUNSHA / BLEND-S Committee Crack Open a Cold Brew with the Girls in this Super Kawaii Working Comedy Premiering this Fall! SANTA MONICA, CA (September 11, 2017) – Aniplex of America has launched the teaser site for the highly anticipated working comedy, BLEND-S. Based on Miyuki Nakayama’s popular manga series by the same name, BLEND-S revolves around a café where each of the employees must play a specific persona while working at the café. Produced by the acclaimed studio A-1 Pictures (Sword Art Online, anohana~The Flower We Saw That Day~), BLEND-S has signed on Yosuke Okuda (High School Fleet, Puella Magi Madoka Magica The Movie Part 3: Rebellion) for Character Designer and Ryoji Masuyama (Gurren Lagann franchise, Occultic;Nine) as Director. BLEND-S is scheduled to premiere on October 7th at 10 AM PDT. BLEND-S’ opening theme song titled “Bon Appéti~tS” will be sung by the 3 main cast members (Azumi Waki, Akari Kito, and Anzu Haruno), who make up the girl group “BlendA” (pronounced Blend Ace). The show introduces a range of female anime archetypes including the classic tsundere personality, the little sister (or imouto) type, and the super bossy sadist or Do-S, as it is known in Japan. “As I’ve completely become a fan of BLEND-S myself, I’m so happy to be voicing Maika,” says Azumi Waki, who plays the main character Maika Sakuranomiya assigned to play the Do-S role in the café. -

Aniplex of America Announces Occultic;Nine Blu-Ray Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 20, 2017 Aniplex of America Announces Paranormal Anime Occultic;Nine for Blu-ray Release and English Dub ©Project OC9/Chiyo st. inc. Nail Biter Horror Suspense Anime Gets English Dub for Blu-ray SANTA MONICA, CA (May 20, 2017) – Aniplex of America Inc. announced at their industry panel at Anime Central (Rosemont, Illinois) that they plan on releasing popular horror suspense anime series Occultic;Nine on Blu-ray this year. Fans of the series were thrilled to learn that the Blu-ray set will also feature an English dub for the first time ever. The set also includes a deluxe booklet, illustration pin-up cards, and special package design illustrated by Character Designer Tomoaki Takase (Saekano: How to Raise a Boring Girlfriend). Pre-orders begin on May 22nd with Volume 1 scheduled to be released on September 26th and Volume 2 on December 26th. Based on the light novel series written by Chiyomaru Shikura (creator of Steins;Gate), Occultic;Nine is animated by renowned studio A-1 Pictures (Sword Art Online, Blue Exorcist, Persona franchise, Magi franchise) and directed by Kyohei Ishiguro (Your lie in April). In addition, the OST is composed by Masaru Yokoyama (Your lie in April, WWW.WAGNARIA!!). The Japanese cast stars Yuki Kaji (Magi franchise, KIZNAIVER, DURARARA!!) as Yuta Gamon, an otaku with a rather pretty face who dreams of quick cash and Ayane Sakura (Nisekoi, Charlotte, Your lie in April) as Ryoka Narusawa, a pale and innocent girl who is very well endowed. The English dub features an all-star cast including Erik Scott Kimerer (Asterisk War, Magi franchise), Robbie Daymond (God Eater, Fate/stay night: Unlimited Blade Works), Erica Lindbeck (ALDNOAH.ZERO, Your lie in April), Cristina Vee (Magi franchise, Puella Magi Madoka Magica), Michelle Ruff (Sword Art Online, Fate/stay night: Unlimited Blade Works, DURARARA!!), and Max Mittelman (Your lie in April, ALDNOAH.ZERO). -

Learning Japanese Through Anime

ISSN 1798-4769 Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 485-495, May 2017 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/jltr.0803.06 Learning Japanese through Anime Yee-Han Chan Faculty of Languages and Linguistics, University of Malaya, Malaysia Ngan-Ling Wong Faculty of Languages and Linguistics, University of Malaya, Malaysia Abstract—While studies have confirmed that there is apparent connection between interest in anime and Japanese language learning among the Japanese language learners (Manion, 2005; Fukunaga, 2006; William, 2006; Abe, 2009), the practical use of anime in teaching Japanese Language as a Foreign Language has not been studied in depth. The present study aimed to discover the language features that can be learned by the Japanese language learners through critical viewing of anime in classroom. A course named “Learning Japanese language through Anime” was carried out in one public university in Malaysia for a duration of 10 weeks. Along with the administration of the course, the participants’ worksheets on language analysis and learning diaries were collected. The findings showed that language used in anime is more casual in most of the contexts involving daily life. This language use is quite different from what the students usually listen to and use in the classroom where the educators heavily emphasis on the polite ways of speaking using the material designed specifically for pedagogical purposes such as textbooks. Although at times, the language presented in anime maybe even harsh or rough in an exaggerated way, rather than ignore this, it may be better to address it critically under the guidance of educator. -

Aniplex of America Announces English Dub and Product Release Details for ERASED

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 1, 2016 Aniplex of America Announces English Dub and Product Release Details for ERASED ©2016 Kei Sanbe/KADOKAWA/Bokumachi Animation Committee Popular Sci-fi Thriller to Receive English Dub and Home Release SANTA MONICA, CA (July 1, 2016) –Aniplex of America announced today at their Anime Expo® industry panel in Los Angeles their plans to release ERASED on Blu-ray starting this fall. The sci-fi thriller anime series based on the award-winning manga by Kei Sanbe will be released in two volume sets with Volume 1 scheduled for release on October 18th of this year and Volume 2 on January 24th of next year. Pre-orders for both volumes will begin today on Aniplex of America’s official ERASED homepage (www.ErasedUSA.com). Simulcast as part of Aniplex’s winter streaming lineup earlier this year, ERASED was produced by an all-star staff including director Tomohiko Ito (Sword Art Online), character designer Keigo Sasaki (Blue Exorcist), composer Yuki Kajiura (Sword Art Online, Fate/Zero, Madoka Magica), and animation studio A-1 Pictures (Sword Art Online, Your lie in April, Blue Exorcist). Aniplex of America also showed the English dub trailer confirming their cast members. Under the direction of Alex von David (Sword Art Online, KILL la KILL, Durarara!!), the dub will star Ben Diskin (Sword Art Online II, KILL la KILL) as Satoru Fujinuma, Michelle Ruff (Sword Art Online II, Durarara!!, GURREN LAGANN) as young Satoru, Sara Cravens as Sachiko Fujinuma, Cherami Leigh (Sword Art Online, Magi) as Airi Katagiri, and Max Mittelman (Your lie in April, Aldnoah.Zero) as Jun Shiratori.