Open As a Single Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Planning and Zoning

Department of Planning and Zoning Subject: Howard County Landscape Manual Updates: Recommended Street Tree List (Appendix B) and Recommended Plant List (Appendix C) - Effective July 1, 2010 To: DLD Review Staff Homebuilders Committee From: Kent Sheubrooks, Acting Chief Division of Land Development Date: July 1, 2010 Purpose: The purpose of this policy memorandum is to update the Recommended Plant Lists presently contained in the Landscape Manual. The plant lists were created for the first edition of the Manual in 1993 before information was available about invasive qualities of certain recommended plants contained in those lists (Norway Maple, Bradford Pear, etc.). Additionally, diseases and pests have made some other plants undesirable (Ash, Austrian Pine, etc.). The Howard County General Plan 2000 and subsequent environmental and community planning publications such as the Route 1 and Route 40 Manuals and the Green Neighborhood Design Guidelines have promoted the desirability of using native plants in landscape plantings. Therefore, this policy seeks to update the Recommended Plant Lists by identifying invasive plant species and disease or pest ridden plants for their removal and prohibition from further planting in Howard County and to add other available native plants which have desirable characteristics for street tree or general landscape use for inclusion on the Recommended Plant Lists. Please note that a comprehensive review of the street tree and landscape tree lists were conducted for the purpose of this update, however, only -

Morphology and Morphogenesis of the Seed Cones of the Cupressaceae - Part II Cupressoideae

1 2 Bull. CCP 4 (2): 51-78. (10.2015) A. Jagel & V.M. Dörken Morphology and morphogenesis of the seed cones of the Cupressaceae - part II Cupressoideae Summary The cone morphology of the Cupressoideae genera Calocedrus, Thuja, Thujopsis, Chamaecyparis, Fokienia, Platycladus, Microbiota, Tetraclinis, Cupressus and Juniperus are presented in young stages, at pollination time as well as at maturity. Typical cone diagrams were drawn for each genus. In contrast to the taxodiaceous Cupressaceae, in Cupressoideae outgrowths of the seed-scale do not exist; the seed scale is completely reduced to the ovules, inserted in the axil of the cone scale. The cone scale represents the bract scale and is not a bract- /seed scale complex as is often postulated. Especially within the strongly derived groups of the Cupressoideae an increased number of ovules and the appearance of more than one row of ovules occurs. The ovules in a row develop centripetally. Each row represents one of ascending accessory shoots. Within a cone the ovules develop from proximal to distal. Within the Cupressoideae a distinct tendency can be observed shifting the fertile zone in distal parts of the cone by reducing sterile elements. In some of the most derived taxa the ovules are no longer (only) inserted axillary, but (additionally) terminal at the end of the cone axis or they alternate to the terminal cone scales (Microbiota, Tetraclinis, Juniperus). Such non-axillary ovules could be regarded as derived from axillary ones (Microbiota) or they develop directly from the apical meristem and represent elements of a terminal short-shoot (Tetraclinis, Juniperus). -

Nursery Catalog

Tel: 503.628.8685 Fax: 503.628.1426 www.eshraghinursery.com 1 Eshraghi’s TOP 10 picks Our locations 1 Main Office, Shipping & Growing 2 Retail Store & Growing 26985 SW Farmington Road Farmington Gardens Hillsboro, OR 97123 21815 SW Farmington Road Beaverton, OR 97007 1 2 3 7 6 3 River Ranch Facility 4 Liberty Farm 4 5 10 N SUNSET HWY TO PORTLAND 8 9 TU HILLSBORO ALA TIN 26 VALL SW 185TH AVE. EY HWY. #4 8 BEAVERTON TONGUE LN. GRABEL RD . D R . E D G R ID E ALOHA R G B D I R R #3 SW 209TH E B T D FARMINGTON ROAD D N A I SIMPSON O O M O R R 10 217 ROSEDALE W R E S W V S I R N W O 219 T K C A J #2 #1 SW UNGER RD. SW 185TH AVE. 1 Acer circinatum ‘Pacific Fire’ (Vine Maple), page 6 D A SW MURRAY BLVD. N RO 2 palmatum (Japanese Maple), NGTO Acer 'Geisha Gone Wild' page 8 FARMI 3 Acer palmatum 'Mikawa yatsubusa' (Japanese Maple), page 10 #1 4 Acer palmatum dissectum 'Orangeola' (Japanese Maple), page 14 5 Hydrangea macrophylla 'McKay', Cherry Explosion PP28757 (Hydrangea), page 32 6 Picea glauca 'Eshraghi1', Poco Verde (White Spruce), page 61 ROAD HILL CLARK 7 Picea pungens 'Hockersmith', Linda (Colorado Spruce), page 64 RY ROAD 8 Pinus nigra 'Green Tower' (Austrian Pine), page 65 SCHOLLS FER 9 Thuja occidentalis 'Janed Gold', Highlights™ PP21967 (Arborvitae), page 70 10 Thuja occidentalis 'Anniek', Sienna Sunset™ (Arborvitae), page 69 Table of contents Tags Make a Difference . -

The Baker's Cypress

AMERICAN CONIFER SOCIETY coniferVOLUME 33, NUMBER 2 | SPRING 2016 QUARTERLY ENCOUNTERS WITH The Baker’s Cypress PAGE 18 SAVE THE DATE • 2016 SOUTHEAST REGION MEETING • AUGUST 26–28 • WAYNESBORO, VA TABLE O F CONTENTS 16 05 18 12 Welcome to the new ConiferQuarterly ACS Seed Exchange and How I Became By Ron Elardo 04 16 a Coniferite By Jim Brackman What Do Conifer Enthusiasts Need to Encounters with The Baker’s Cypress Know About Mycorrhizae? 05 18 By David Pilz By Bert Cregg, Ph.D. Comments on Conifers for Open Forum: Southeast Region ACS Part 1 09 22 Reference Gardens By Bob Fincham 2016 Southeast Region Meeting ACS Directorate By Jeff Harvey 12 23 Shady Characters: Conifers and Plants Made For Shade 14 By Rich and Susan Eyre Spring 2016 Volume 33, Number 2 ConiferQuarterly (ISSN 8755-0490) is published quarterly by the American Conifer Society. The Society is a non- Conifer profit organization incorporated under the laws of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and is tax exempt under Quarterly section 501(c)3 of the Internal Revenue Service Code. You are invited to join our Society. Please address Editor membership and other inquiries to the American Conifer Ronald J. Elardo Society National Office, PO Box 1583, Minneapolis, MN 55311, [email protected]. Membership: US & Canada $38, International $58 (indiv.), $30 (institutional), $50 Technical Editors (sustaining), $100 (corporate business) and $130 (patron). Steven Courtney If you are moving, please notify the National Office 4 weeks Robert Fincham in advance. Ethan Johnson David Olszyk All editorial and advertising matters should be sent to: Ron Elardo, 5749 Hunter Ct., Adrian, MI 49221-2471, (517) 902-7230 or email [email protected] Advisory Committee Tom Neff, Committee Chair Copyright © 2016, American Conifer Society. -

Plant List for Stanford Garden

Plant List for Stanford Garden Genus Species Variety Common Name Abelia grandiflora Edward Goucher Glossy Abelia Abies balsamea Nana Dwarf Balsam Fir Abies concolor Candicans Colorado White Fir Abies concolor Compacta Dwarf Colorado White Fir Abies koreana Aurea Golden Korean Fir Abies koreana Hortsmann's Silberlocke Korean Fir Abies koreana Silber Mavers Korean Fir Abies lasiocarpa Arizonica Compacta Glauca Cork Bark Fir Abies nordmanniana Golden Spreader Caucasian Fir Abies pinsapo Glauca Blue Spanish Pin Fir Acer palmatum Fire Glow Japanese Maple Acer palmatum Kurui Jishi Crazy Lion Japanese Maple Acer palmatum Sango Kaku Coral Bark Maple Acer palmatum Shishigashira Lion's Head Japanese Maple Acer palmatum dissectum Crimson Queen Japanese Maple Acer palmatum dissectum Garnet Japanese Maple Adiantum pendantum Maidenhair Fern Ajuga Mahogany Ajuga Allium schubertii Ornamental Onion Allium siculum Ornamental Onion Allium Gladiator Ornamental Onion Allium Purple Sensation Ornamental Onion Amsonia tabernaemontana Blue Star Willow Andromeda polifolia Bog Rosemary Anemanthele lessoniana New Zealand Wind Grass Genus Species Variety Common Name Anemone coronaria de Caen Wind Flower Anemone hupehensis japonica September Charm Japanese Anemone Anemone huphensis japonica Pamina Japanese Anemone Anemone x hybrida Honorine Jobert Japanese Anemone Angelica Aquilegia vulgaris Lime Frost Columbine Aquilegia Woodside Golden Columbine Aquillega Yellow Queen Yellow Columbine Arabis caucasica Variegata Variegated Rock Cress Arisaema formosanum DJHT 99049 Armeria maritima Alba White Sea Thrift Armeria maritima Dusseldorf Pride Sea Thrift Armeria pseudarmeria Arrhenatherum elatius ssp. Bulbosum Variegatum Striped Tuber Oat Grass Artemisia Oriental Limelinght Wormwood Artemisia Powis Castle Wormwood Arum italicum Wild Ginger Aruncus aethusifolius Dwarf Korean Goat's Beard Arundo donax Variegata Striped Giant Reed Arundo donax Giant Reed Asparagus densiflorus Myers Asparagus Fern/Pony Tail Fern Asplenium scolopendrium Hart's Tounge Fern Aster dumosus Prof A. -

Chamaecyparis Obtusa (Hinoki Falsecypress) Hinoki Falsecypress Is a Conical-Shaped Evergreen Native to Japan

Chamaecyparis obtusa (Hinoki Falsecypress) Hinoki Falsecypress is a conical-shaped evergreen native to Japan. It has flat, fern-like, scaled leaves with white bands underneath. Its reddish-brown bark peels in long strips. There are many cultivars with different foliage coloration and growth habits. Landscape Information French Name: Cyprès du Japon, Hinoki Faux- Cyprès Pronounciation: kam-eh-SIP-uh-riss ob-TOO- suh Plant Type: Tree Origin: Japan Heat Zones: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Hardiness Zones: 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Uses: Screen, Hedge, Topiary, Bonsai, Espalier, Border Plant, Container, Windbreak Size/Shape Growth Rate: Slow Tree Shape: Pyramidal Canopy Symmetry: Symmetrical Canopy Density: Dense Canopy Texture: Fine Height at Maturity: Less than 0.5 m, 0.5 to 1 m, 1 to 1.5 m, 1.5 to 3 m, 3 to 5 m, 5 to 8 m, 8 to 15 m, 15 to 23 m Spread at Maturity: Less than 50 cm, 0.5 to 1 meter, 1 to 1.5 meters, 1.5 to 3 meters, 3 to 5 meters Plant Image Chamaecyparis obtusa (Hinoki Falsecypress) Botanical Description Foliage Leaf Arrangement: Opposite Leaf Venation: Nearly Invisible Leaf Persistance: Evergreen Leaf Type: Simple Leaf Blade: Less than 5 Leaf Shape: Scale Leaf Margins: Entire Leaf Textures: Medium Leaf Scent: Pleasant Color(growing season): Green Color(changing season): Green Leaf Image Flower Flower Showiness: False Flower Size Range: 0 - 1.5 Flower Scent: No Fragance Flower Color: Yellow Trunk Trunk Has Crownshaft: False Trunk Susceptibility to Breakage: Generally resists breakage Number of Trunks: Single Trunk Trunk Esthetic Values: Showy, -

Chamaecyparis Obtusa Hinoki Falsecypress1 Edward F

Fact Sheet ST-156 November 1993 Chamaecyparis obtusa Hinoki Falsecypress1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 INTRODUCTION This broad, sweeping, conical-shaped evergreen has graceful, flattened, fern-like branchlets which gently droop at branch tips (Fig. 1). Hinoki Falsecypress reaches 50 to 75 feet in height with a spread of 10 to 20 feet, has dark green foliage, and attractive, shredding, reddish-brown bark which peels off in long narrow strips. GENERAL INFORMATION Scientific name: Chamaecyparis obtusa Pronunciation: kam-eh-SIP-uh-riss ob-TOO-suh Common name(s): Hinoki Falsecypress Family: Cupressaceae USDA hardiness zones: 5 through 8A (Fig. 2) Origin: not native to North America Uses: Bonsai; screen Availability: somewhat available, may have to go out of the region to find the tree DESCRIPTION Height: 40 to 75 feet Spread: 10 to 20 feet Crown uniformity: symmetrical canopy with a regular (or smooth) outline, and individuals have more or less identical crown forms Figure 1. Mature Hinoki Falsecypress. Crown shape: pyramidal Crown density: dense Foliage Growth rate: medium Texture: fine Leaf arrangement: opposite/subopposite Leaf type: simple Leaf margin: entire 1. This document is adapted from Fact Sheet ST-156, a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. Publication date: November 1993. 2. Edward F. Gilman, associate professor, Environmental Horticulture Department; Dennis G. Watson, associate professor, Agricultural Engineering Department, Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville FL 32611. Chamaecyparis obtusa -- Hinoki Falsecypress Page 2 Figure 2. Shaded area represents potential planting range. -

A POPULAR DICTIONARY of Shinto

A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto BRIAN BOCKING Curzon First published by Curzon Press 15 The Quadrant, Richmond Surrey, TW9 1BP This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.” Copyright © 1995 by Brian Bocking Revised edition 1997 Cover photograph by Sharon Hoogstraten Cover design by Kim Bartko All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-203-98627-X Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-7007-1051-5 (Print Edition) To Shelagh INTRODUCTION How to use this dictionary A Popular Dictionary of Shintō lists in alphabetical order more than a thousand terms relating to Shintō. Almost all are Japanese terms. The dictionary can be used in the ordinary way if the Shintō term you want to look up is already in Japanese (e.g. kami rather than ‘deity’) and has a main entry in the dictionary. If, as is very likely, the concept or word you want is in English such as ‘pollution’, ‘children’, ‘shrine’, etc., or perhaps a place-name like ‘Kyōto’ or ‘Akita’ which does not have a main entry, then consult the comprehensive Thematic Index of English and Japanese terms at the end of the Dictionary first. -

2021 Plant List

2021 Plant List New items are listed with an asterisk (*) Conifers Pinus thungerbii Abies koreana 'Horstmann's Silberlocke' Pinus x 'Jane Kluis' * Chamaecyparis nootkatensis 'Pendula' Sciadopitys vert. 'Joe Dozey' Chamaecyparis noot. 'Glauca Pendula' Sciadopitys vert. 'Wintergreen' Chamaecyparis obtusa 'Chirimen' * Taxodium distichum 'Pendula' Chamaecyparis obtusa 'Gracilis' -Select Taxodium distichum 'Peve Mineret' Chamaecyparis obtusa 'Kosteri' Taxus cuspidaata 'Nana Aurescens' Chamaecyparis obtusa 'Nana' Tsuga con. 'Jervis' Chamaecyparis obtusa 'Nana Gracilis' Chamaecyparis obtusa 'Spiralis' Ferns Chamaecyparis obtusa 'Thoweil' Adiantum pedatum ….Maiden Hair Chamaecyparis obtusa 'Verdoni' Athyrum filix-femina 'Minutissima' Juniperus procumbens 'Nana' Athyrium 'Ghost' Larix decidua 'Pendula' Athyrum niponicum 'Godzilla' Larix decidua 'Pendula' -Prostrate Form Athyrum niponicum 'Pictum' Picea abies 'Hasin' * Athyrum niponicum pic. 'Pearly White' Picea abies 'Pusch' * Dennstaedtia punctilobula Picea omorika 'Nana' Dryopteris ery. 'Brilliance' Picea omorika 'Pendula' Dryopteris marginalis Picea orientalis 'Nana' Matteucciastruthiopteris var. pensylvanica Picea orientalis 'Shadow's Broom' * Osmunda cinnamomea Picea pungens 'Glauca Globosa' Polystichum acrostichoides Pinus mugo 'Mughus' - Rock Garden Strain Polystichum polyblepharum Pinus mugo 'Slowmound' Pinus nigra 'Hornibrookiana' Grasses Pinus parviflora 'Aoi' These are but a fraction of the grasses we'll be Pinus parviflora 'Glauca Nana' offering this year. Many more to come. They'll -

IHCA Recommended Plant List

Residential Architectural Review Committee Recommended Plant List Plant Materials The following plant materials are intended to guide tree and shrub ADDITIONS to residential landscapes at Issaquah Highlands. Lot sizes, shade, wind and other factors place size and growth constraints on plants, especially trees, which are suitable for addition to existing landscapes. Other plant materials may be considered that have these characteristics and similar maintenance requirements. Additional species and varieties may be selected if authorized by the Issaquah Highlands Architectural Review Committee. This list is not exhaustive but does cover most of the “good doers” for Issaquah Highlands. Our microclimate is colder and harsher than those closer to Puget Sound. Plants not listed should be used with caution if their performance has not been observed at Issaquah Highlands. * Drought-tolerant plant ** Requires well-drained soil DECIDUOUS TREES: Small • Acer circinatum – Vine Maple • Acer griseum – Paperbark Maple • *Acer ginnala – Amur Maple • Oxydendrum arboreum – Sourwood • Acer palmation – Japanese Maple • *Prunus cerasifera var. – Purple Leaf Plum varieties • Amelanchier var. – Serviceberry varieties • Styrax japonicus – Japanese Snowbell • Cornus species, esp. kousa Medium • Acer rufinerve – Redvein Maple • Cornus florida (flowering dogwood) • *Acer pseudoplatanus – Sycamore Maple • Acer palmatum (Japanese maple, many) • • *Carpinus betulus – European Hornbeam Stewartia species (several) • *Parrotia persica – Persian Parrotia Columnar Narrow -

Conifer Quarterly

Conifer Quarterly Vol. 21 No. 2 Spring 2004 P hot os b y G ar y W hitt enbaugh Gary Whittenbaugh can’t resist incorporating Chamaecyparis into his Iowa garden, while at the same time he warns against becoming too attached to them. Read about these plants’ role in the Midwest on page 20. Shown here are (top) C. pisifera ‘Plumosa Compressa’ as a background plant, ‘Golden Mop’ in the fall (left) and Gary’s favorite,‘Snow.’ Grafting is an important part of conifer propagation, from the largest nurseries to the hobbyist plant collector. Review the basics of side grafting on page 30, as taught by expert George Okken. een r y G on T The Conifer Quarterly is the publication of The Conifer Society Contents Featured conifer genus: Chamaecyparis 6 Resurrecting Lawson Cypress for the 21st Century Tanya DeMarsh-Dodson 12 Seedling Conifers Offer Challenge and Variety Peter C. Jones 16 Origin, Distribution and Variation of Atlantic White-cedar Kristin Mylecraine and John Kuser 20 Reader Recommendations More features 24 Hands Across the Sea Derek Spicer 29 Obituary: Bob Tomayer 30 The Art and Science of Grafting: A Demonstration by George Okken Anne M. Brennan 38 One Acre in Rochester Gerald P. Kral Conifer Society voices 2 President’s Message 4 Editor’s Memo 15 Conifers on the Web 23 Puzzle Page 42 Central Region Builds on Past Success 43 Western Region Update 44 Northeast Region to Visit the “Flower City” 46 Southeast Region Announces Itinerary Cover photo: An unusually cold Pennsylvania winter melts away with the snow from Chamaecyparis obtusa ‘Crippsii’,just as last year’s muted foliage will soon disappear behind the glowing golden spring flush for which this cultivar is known. -

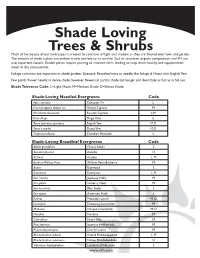

Shade Loving Trees & Shrubs

Shade Loving Trees & Shrubs Much of the beauty of our landscapes is created by contrasts of light and shadow as they are filtered over lawn and garden. The amount of shade a plant can endure is only one key to its survival. Soil; its structure, organic composition, and PH are also important factors. Shaded plants require pruning to maintain form, feeding to keep them healthy, and supplemental water in dry time periods. Foliage contrasts are important in shade gardens. Example: Broadleaf next to needle-like foliage & Hosta with English Yew. Few plants flower heavily in dense shade; however, flowers in partial shade last longer and don’t fade as fast as in full sun. Shade Tolerance Code: L=Light Shade, M=Medium Shade, D=Dense Shade Shade-Loving Needled Evergreens Code Abies concolor Concolor Fir L Chamaecyparis obtusa cvs. Hinoki Cypress M Microbiota decussata Russian Cypress L,M Pinus Mugo Mugo Pine L Taxus baccata repandens English Yew M,D Taxus x media Densa Yew M,D Tsuga canadensis Canadian Hemlock L Shade-Loving Broadleaf Evergreens Code Abelia grandiflora Glossy Abelia L Aucuba japonica Aucuba D Azaleas Azaleas L, M Berberis William Penn William Penn Barberry M Buxus Boxwood L Euonymus Euonymus L, M Ilex crenata Japanese Holly M Ilex glabra Inkberry Holly M Ilex meservae Blue Holly L Ilex opaca American Holly L Kalmia Mountain Laurel M, D Leucothoe Drooping Leucothoe M Mahonia Oregon Grapeholly M, D Nandina Nandina M Osmanthus False Holly M Pieis japonica Japanese Andromeda M Prunus laurocerasus Cherry Laurel M Rhododendron hybrids Hybrid Rhododendron L, M Rhododendron maximum Native Rhododendron D Viburnum rhytidophyllum Leatherleaf Viburnum L www.skh.com Shade-Loving Deciduous Shrubs Code Aronia arbutifolia Chokeberry M Calycanthus floridus Sweetshrub L, M Clethra alnifolia Summersweet M Cotoneaster Cotoneaster L, M Forsythia Forsythia L, M Hamamelis Witch-Hazel L Hydrangea Hydrangea L, M Hypericum St.