Top of Page Interview Information--Different Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HHI Front Matter

A PUBLIC TRUST AT RISK: The Heritage Health Index Report on the State of America’s Collections HHIHeritage Health Index a partnership between Heritage Preservation and the Institute of Museum and Library Services ©2005 Heritage Preservation, Inc. Heritage Preservation 1012 14th St. Suite 1200 Washington, DC 20005 202-233-0800 fax 202-233-0807 www.heritagepreservation.org [email protected] Heritage Preservation receives funding from the National Park Service, Department of the Interior. However, the content and opinions included in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior. Table of Contents Introduction and Acknowledgements . i Executive Summary . 1 1. Heritage Health Index Development . 3 2. Methodology . 11 3. Characteristics of Collecting Institutions in the United States. 23 4. Condition of Collections. 27 5. Collections Environment . 51 6. Collections Storage . 57 7. Emergency Plannning and Security . 61 8. Preservation Staffing and Activitives . 67 9. Preservation Expenditures and Funding . 73 10. Intellectual Control and Assessment . 79 Appendices: A. Institutional Advisory Committee Members . A1 B. Working Group Members . B1 C. Heritage Preservation Board Members. C1 D. Sources Consulted in Identifying the Heritage Health Index Study Population. D1 E. Heritage Health Index Participants. E1 F. Heritage Health Index Survey Instrument, Instructions, and Frequently Asked Questions . F1 G. Selected Bibliography of Sources Consulted in Planning the Heritage Health Index. G1 H. N Values for Data Shown in Report Figures . H1 The Heritage Health Index Report i Introduction and Acknowledgements At this time a year ago, staff members of thou- Mary Chute, Schroeder Cherry, Mary Estelle sands of museums, libraries, and archives nation- Kenelly, Joyce Ray, Mamie Bittner, Eileen wide were breathing a sigh of relief as they fin- Maxwell, Christine Henry, and Elizabeth Lyons. -

Pacific Standard Time: Art in La

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contacts Ruder Finn Arts & Communications Counselors Rachel Bauch (310) 882-4013 / [email protected] Olivia Wareham (212) 583-2754 / [email protected] PACIFIC STANDARD TIME: ART IN L.A. 1945-1980 BEGINS THE COUNTDOWN TO ITS OCTOBER 2011 OPENING Bank of America Joins as Presenting Sponsor; Community Leaders and Foundations Expand the Ever-Growing Circle of Support New Partnerships, Exhibitions, Outreach Programs and Performance Art and Public Art Festival Are Announced for the Unprecedented Region-Wide Collaboration Los Angeles, CA, November 4, 2010 — Deborah Marrow, Interim President and CEO of the J. Paul Getty Trust, joined today with cultural and civic leaders from throughout Southern California to announce a host of new initiatives, partnerships, exhibitions and programs for the region-wide initiative Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945-1980, including presenting sponsorship from Bank of America. The first project of its kind, Pacific Standard Time has now begun the countdown to its October 2011 opening, when more than sixty cultural institutions throughout Southern California will come together to tell the story of the birth of the Los Angeles art scene and how it became a new force in the art world. This collaboration, the largest ever undertaken by cultural institutions in the region, will continue through April 2012. It has been initiated through grants totaling $10 million from the Getty Foundation. ―As we start marking the days toward the opening, the excitement about Pacific Standard Time continues to grow, and so does the project itself,‖ Deborah Marrow stated. ―What began as an effort to document the milestones in this region’s artistic history has expanded until it is now becoming a great creative landmark in itself. -

Press Release

NEWS FROM THE GETTY news.getty.edu | [email protected] DATE: October 2, 2019 MEDIA CONTACT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Julie Jaskol Getty Communications (310) 440-7607 [email protected] DEBORAH MARROW LED GETTY FOUNDATION FOR 30 YEARS Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Trust LOS ANGELES – Deborah Marrow, who retired as director of the Getty Foundation at the end of last year after more than three decades of leadership in various roles at the Getty, including two stints as interim president, died early Tuesday morning. “No one has contributed more to the life and mission of the Getty than Deborah, and we will miss her deeply,” said James Cuno, president and CEO of the J. Paul Getty Trust. “She provided inspiring leadership in almost every aspect of the Getty, in roles including director of the Getty Foundation, acting director of the Getty Research Institute, and interim president of the Getty Trust. She brought clarity, vision, and selfless dedication to her work, and made loyal professional friends around the world.” As Foundation director, Marrow oversaw all grantmaking activity locally and worldwide in the areas of art history, conservation, and museums, as well as grants administration for all of the programs and departments of the J. Paul Getty Trust. The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 403 Tel: 310 440 7360 www.getty.edu Communications Department Los Angeles, CA 90049-1681 Fax: 310 440 7722 Cuno noted that one of Marrow’s proudest accomplishments was the creation of the Getty’s Multicultural Undergraduate Internship program, which over 27 years has dedicated over $14 million to support more than 3,400 internships at 160 local arts institutions in a pioneering effort to increase staff diversity in museums and visual arts organizations. -

Pacific Standard Time Presents: Modern Architecture in L.A

DATE: April 8, 2013 MEDIA CONTACT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Julie Jaskol Getty Communications (310) 440-7607 [email protected] GETTY LAUNCHES PACIFIC STANDARD TIME PRESENTS: MODERN ARCHITECTURE IN L.A. Initiative Begins April 9; Examines L.A.’s Modern Architectural Heritage April–July 2013 LOS ANGELES—The Getty launched Pacific Standard Time Presents: Modern Architecture in L.A. today, with a celebration of L.A. architecture featuring presentations by Getty President and CEO Jim Cuno, The Honorable Antonio Villaraigosa, architectural historian Thomas S. Hines, author and documentarian Charles Phoenix, and innovative musicians the Calder Quartet. A collaborative celebration of one of Southern California’s most lasting contributions to post-World War II cultural life, Pacific Standard Time Presents: Modern Architecture in L.A. continues the momentum of Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A., 1945–1980, the sweeping initiative in 2011–2012 that included exhibitions and programs at over 60 arts institutions across Southern Department of Water and Power Building Corner with California. Pacific Standard Time Presents: Modern Fountains, 1965. Photo: Julius Shulman (American, 1910–2009). Gelatin silver print. The Getty Research Architecture in L.A., is smaller in scope, comprising Institute, Los Angeles. © J. Paul Getty Trust eleven exhibitions and accompanying programs and events in and around Los Angeles continuing through July 2013. -more- Page 2 “We wanted to expand our exploration of the region’s postwar visual arts and culture, but obviously we can’t do an initiative on the scale of Pacific Standard Time every year,” said Cuno. “Pacific Standard Time Presents is smaller in size and geographic reach, but again spurs original scholarship and maintains the collaborative spirit of Pacific Standard Time.” Pacific Standard Time Presents: Modern Architecture in L.A. -

S P R I N G 2 0 2 0 N E W S L E T T

SPRING 2020 NEWSLETTER HISTORY OF ART DEPARTMENT AT THE UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA LETTER FROM THE CHAIR Dear Alums and Friends, I hope the following pages will convey a vivid impression of the life and activities of Penn’s History of Art Department during 2019. The author of this letter from the chair for the last four years, Karen Redrobe, completed her term in June. Since then I have taken up the duties of department chair with the excellent assistance of Julie Nelson Davis as graduate chair and André Dombrowski as undergraduate chair. The accomplishments of Karen Redrobe’s term are extraordinary. Above all she managed a concentrated generational turnover in the department, which involved facilitating the retirements of seven long-serving senior colleagues and spearheading the hiring of four superb new additions (Sarah Guérin, Ivan Drpić, Mantha Zarmakoupi, and Shira Brisman). Two further appointments, which she negotiated with the dean’s office, are being filled this year. In addition, she attended to the needs of students and faculty with great sensitivity, and she made issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion paramount in department policies and activities. Luckily the supporting staff who assisted with these achievements—that is, our exceptional administrators Darlene Jackson and Libby Saylor—continue to keep the bureaucratic machinery softly humming with the new leadership team. Spring term was the last of Renata Holod’s forty-seven-year career as a teacher at Penn. Her contributions to shaping the department as it exists today are immeasurable. In Fall 2019 we learned that the Mellon Foundation had approved our application for renewed funding to continue our partnership with the Philadelphia Museum of Art to promote object-based study. -

Press Release

NEWS FROM THE GETTY news.getty.edu | [email protected] DATE: July 8, 2019 MEDIA CONTACT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Alexandria Sivak Getty Communications (310) 440-6473 [email protected] JOAN WEINSTEIN TO LEAD GETTY FOUNDATION Joan Weinstein. Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Trust LOS ANGELES – The J. Paul Getty Trust announced today the appointment of Dr. Joan Weinstein as the new director of the Getty Foundation after an international search. Weinstein is currently acting director of the Getty Foundation, where she has been deputy director since 2007 and has served in various roles since 1994. “The Getty Foundation is committed to serving the fields of art history, conservation, and museums, and there are few people who understand the professional needs in these areas more than Joan Weinstein,” says Jim Cuno, president and CEO of the J. Paul Getty Trust. “Her deep knowledge of the visual arts and of strategic philanthropy has led to the creation of meaningful initiatives that have supported groundbreaking research and exhibitions, international scholarly exchange, training for museum professionals in sub-Saharan Africa, and so much more. Joan’s experience is invaluable, and I look forward to her taking the Foundation to a new level.” Weinstein has served the Getty as acting director of the Foundation on two previous occasions, and has also served as associate director, senior program officer, and program officer over the course of her career. In her recent role as deputy director Weinstein oversaw strategic direction in grantmaking, led the development of new grant initiatives, and established metrics to assess funding impact. -

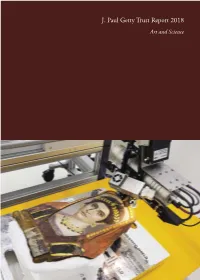

J. Paul Getty Trust Report 2018 Art and Science J

J. Paul Getty Trust Report 2018 Art and Science J. Paul Getty Trust Report 2018 On the cover: Macro-XRF scanning of mummy portrait Isidora, AD 100–110. Encaustic on linden wood; gilt; linen. The J. Paul Getty Museum Table of Contents 3 Chair Message Maria Hummer-Tuttle, Chair, Board of Trustees 7 Foreword James Cuno, President and CEO, J. Paul Getty Trust 10 Art and Science 11 Thoughts on Art and Science David Baltimore, President Emeritus and Robert Andrews Millikan Professor of Biology at the California Institute of Technology 15 Getty Conservation Institute Timothy P. Whalen, John E. and Louise Bryson Director 27 Getty Foundation Deborah Marrow, Director 39 J. Paul Getty Museum Timothy Potts, Director 49 Getty Research Institute Andrew Perchuk, Acting Director 59 Trust Report Lists 60 Getty Conservation Institute Projects 72 Getty Foundation Grants 82 Exhibitions and Acquisitions 110 Getty Guest Scholars 114 Getty Publications 122 Getty Councils 131 Honor Roll of Donors 139 Board of Trustees, Officers, and Directors 141 Financial Information Chair Message MARIA HUMMER-TUTTLE, CHAIR, BOARD OF TRUSTEES J. Paul Getty Trust ART AND SCIENCE—the theme of this year’s Trust Time: Art in L.A. 1945–1980, which ran from October Report—merge seamlessly in the Getty’s work of 2011 to April 2012. preserving, protecting, and interpreting the world’s While the majority of PST: LA/LA exhibitions artistic legacy. In the following essays by our four showcased modern and contemporary art, exhibitions program directors, you will learn how these disciplines about the ancient world and the pre-modern era were inform the work of the Getty Conservation Institute, also included. -

J. Paul Getty Museum

l efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN: 93491132017356 OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation 2014 0- Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury 0- Information about Form 990-PF and its instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990Pf . Open to Pu b lic Internal Revenue Service ITSBeCUOT For calendar year 2014, or tax year beginning 07 - 01-2014 , and ending 06-30-2015 Name of foundation A Employer identification number The I Paul Getty Trust 95-1790021 O/o WILLIAM G HUMPHRIES Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/ suite U ieiepnone number (see instructions) 1200 Getty Center Dr 401 (310) 440-6040 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here F Los Angeles, CA 90049 G Check all that apply r'Initial return r'Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations , check here F r Final return r'Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 850/, r- Address change r'Name change test, check here and attach computation F E If private foundation status was terminated H C heck type of organization FSection 501( c)(3) exempt private foundation und er section 507 ( b )( 1 )( A ), c hec k here F_ Section 4947 (a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust r'Other taxable private foundation I Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method F Cash F Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60 - month termination of year (from Part II, col. -

Culture in Concrete

CULTURE IN CONCRETE: Art and the Re-imagination of the Los Angeles River as Civic Space by John C. Arroyo B.A., Public Relations Minor, Urban Planning and Development University of Southern California, 2002 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF URBAN STUDIES AND PLANNING IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER IN CITY PLANNING at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2010 © 2010 John C. Arroyo. All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. THESIS COMMITTEE A committee of the Department of Urban Studies and Planning has examined this Masters Thesis as follows: Brent D. Ryan, PhD Assistant Professor in Urban Design and Public Policy Thesis Advisor Susan Silberberg-Robinson, MCP Lecturer in Urban Design and Planning Thesis Reader Los Angeles River at the historic Sixth Street Bridge/Sixth Street Viaduct. © Kevin McCollister 2 CULTURE IN CONCRETE: Art and the Re-imagination of the Los Angeles River as Civic Space by John C. Arroyo Submitted to the Department of Urban Studies and Planning on May 20, 2010 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master in City Planning ABSTRACT The Los Angeles River is the common nature of the River space. They have expressed physical, social, and cultural thread that themselves through place-based work, most of connects many of Los Angeles’ most diverse and which has been independent of any formal underrepresented communities, the majority of urban planning, urban design, or public policy which comprise the River’s downstream support or intervention. -

Brian Considine, Senior Conservator of Decorative Arts & Architecture at the J

Oral History Center University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Conservation and Craftsmanship: Brian Considine, Senior Conservator of Decorative Arts & Architecture at The J. Paul Getty Museum Interviews conducted by Cristina Kim in 2017 Interviews sponsored by the J. Paul Getty Trust Copyright © 2017 by J. Paul Getty Trust Oral History Center, The Bancroft Library, University of California Berkeley ii Since 1954 the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library, formerly the Regional Oral History Office, has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. -

Spring-Summer 1984 CAA Newsletter

newsletter Volume 9, Number 1-2 Spring-Summer 1984 1985 annual meeting: studio sessions Studio sessions for the 1985 annual meeting in Los Angeles have Crossovers: Artists, Architects, and Landscape Architects. Don been planned by James Melchert, formerly chair of the art depart lyn Lyndon, University of California, Department of Art, 201 Camp ment at the University of California, Berkeley, currently director of bell Hall, Berkeley, Calif. 94720. the American Academy in Rome, Listed below are the topics he has Artworks in public places can benefit from the attention of many selected. Those wishing to participate in any session must submit pro different types of designers and artists, who bring their special ways of posals to the chair of that session by October I, 1984. Note: Art history imagining into a particular place and situation. The education of art session topics were announced in a special mailing in March. If your ists, architects, and landscape architects could profitably include ex copy has been lost in themail, chewed-up by the dog, or stolen by a col perience in such collaborative working process. A number of issues league: an additional copy may be obtained from the CAA office. need to be examined; these include establishing working conditions Please send $1.00 for postage and handling. such that each participant can bring his or her particular way of mak ing connections with previous work into a common discussion and ex Film in the Video Era: Survival of the Mediums. Julie Lazar, ploration of one particular site; encouraging people to look beyond the Museum of Contemporary Art, 152 North Central Avenue, Los specialized skills and techniques that serve as badges of competence in Angeles, Calif. -

Pacific Standard Time: Art in La

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contacts Ruder Finn Arts & Communications Counselors Whitney Snow (212) 583-2743 / [email protected] Amy Hood (310) 882-4015 / [email protected] PACIFIC STANDARD TIME: ART IN L.A. 1945-1980 COUNTS DOWN TO OCTOBER 2011 OPENING Unprecedented Region-Wide Collaboration Includes More Than 60 Cultural Partners, More than 50 Exhibitions and a Ten-Day Performance Art Festival Bank of America Lends Support as the Presenting Sponsor of Pacific Standard Time New York, NY, February 9, 2011 — Opening on October 1, 2011, Pacific Standard Time will bring together more than sixty cultural institutions throughout Southern California to tell the story of the rise of the Los Angeles art scene and how it became a new force in the art world. This collaboration, the largest ever undertaken by cultural institutions in the region, will continue through April 2012. It has been initiated by the Getty Foundation through grants totaling $10 million. Exploring and celebrating the significance of the crucial years after World War II through the tumultuous period of the 1960s and 70s, Pacific Standard Time encompasses developments from L.A. Pop to post-minimalism; from modernist architecture and design to multi-media installations; from the films of the African-American L.A. Rebellion to the feminist activities of the Woman’s Building; from ceramics to Chicano performance art; and from Japanese- American design to the pioneering work of artists’ collectives. “As we mark the days toward the opening, the excitement about Pacific Standard Time continues to grow, and so does the project itself,” Deborah Marrow, interim President and CEO of the J.