25Th Anniversary Report.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release

NEWS FROM THE GETTY news.getty.edu | [email protected] DATE: June 5, 2019 MEDIA CONTACTS: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Julie Jaskol Getty Communications (310) 440-7607 [email protected] J. PAUL GETTY TRUST BOARD OF TRUSTEES ELECTS DR. DAVID L. LEE AS CHAIR Dr. David L. Lee has served on the Board since 2009; he begins his four-year term as chair on July 1 LOS ANGELES—The Board of Trustees of the J. Paul Getty Trust today announced it has elected Dr. David L. Lee as its next chair of the Board. “We are delighted that Dr. Lee will lead the Getty Board of Trustees as we embark on many exciting initiatives,” said Getty President James Cuno. “Dr. Lee’s involvement with the international community, his experience in higher education and philanthropy, and his strong financial acumen has served the Getty well. We look forward to his leadership.” Dr. Lee was appointed to the Getty Board of Trustees in 2009. Dr. Lee will serve a four-year term as chair of the 15-member group that includes leaders in art, education, and business who volunteer their time and expertise on behalf of the Getty. “Through its extensive research, conservation, exhibition and education programs, the Getty’s work has made a powerful impact not only on the Los Angeles region, but around the world,” Dr. Lee said. “I am honored to be part of such a generous, inspiring organization that makes a lasting difference and is a source of great pride for our community.” The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 403 Tel: 310 440 7360 www.getty.edu Communications Department Los Angeles, CA 90049-1681 Fax: 310 440 7722 Dr. -

Press Image Sheet

NEWS FROM THE GETTY news.getty.edu | [email protected] DATE: September 17, 2019 MEDIA CONTACT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Julie Jaskol Getty Communications (310) 440-7607 [email protected] GETTY TO DEVOTE $100 MILLION TO ADDRESS THREATS TO THE WORLD’S ANCIENT CULTURAL HERITAGE Global initiative will enlist partners to raise awareness of threats and create effective conservation and education strategies Participants in the 2014 Mosaikon course Conservation and Management of Archaeo- logical Sites with Mosaics conduct a condition survey exercise of the Achilles Mosaic at the Paphos Archeological Park, Paphos, Cyprus. Continued work at Paphos will be undertaken as part of Ancient Worlds Now. Los Angeles – The J. Paul Getty Trust will embark on an unprecedented and ambitious $100- million, decade-long global initiative to promote a greater understanding of the world’s cultural heritage and its universal value to society, including far-reaching education, research, and conservation efforts. The innovative initiative, Ancient Worlds Now: A Future for the Past, will explore the interwoven histories of the ancient worlds through a diverse program of ground-breaking The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 403 Tel: 310 440 7360 www.getty.edu Communications Department Los Angeles, CA 90049-1681 Fax: 310 440 7722 scholarship, exhibitions, conservation, and pre- and post- graduate education, and draw on partnerships across a broad geographic spectrum including Asia, Africa, the Americas, the Middle East, and Europe. “In an age of resurgent populism, sectarian violence, and climate change, the future of the world’s common heritage is at risk,” said James Cuno, president and CEO of the J. -

Getty and Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage Announce Major Enhancements to Ghent Altarpiece Website

DATE: August 20, 2020 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE IMAGES OF THE RESTORED ADORATION OF THE LAMB AND MORE: GETTY AND ROYAL INSTITUTE FOR CULTURAL HERITAGE ANNOUNCE MAJOR ENHANCEMENTS TO GHENT ALTARPIECE WEBSITE Closer to Van Eyck offers a 100 billion-pixel view of the world-famous altarpiece, to be enjoyed from home http://closertovaneyck.kikirpa.be/ The Lamb of God on the central panel, from left to right: before restoration (with the 16th-century overpaint still present), during restoration (showing the van Eycks’ original Lamb from 1432 before retouching), after retouching (the final result of the restoration) LOS ANGELES AND BRUSSELS – Since 2012, the website Closer to Van Eyck has made it possible for millions around the globe to zoom in on the intricate, breathtaking details of the Ghent Altarpiece, one of the most celebrated works of art in the world. More than a quarter million people have taken advantage of the opportunity so far in 2020, and website visitorship has increased by 800% since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, underscoring the potential for modern digital technology to increase access to masterpieces from all eras and learn more about them. The Getty and the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (KIK-IRPA, Brussels, Belgium), in collaboration with the Gieskes Strijbis Fund in Amsterdam, are giving visitors even more ways to explore this monumental work of art from afar, with the launch today of a new version of the site that includes images of recently restored sections of the paintings as well as new videos and education materials. Located at St. -

HHI Front Matter

A PUBLIC TRUST AT RISK: The Heritage Health Index Report on the State of America’s Collections HHIHeritage Health Index a partnership between Heritage Preservation and the Institute of Museum and Library Services ©2005 Heritage Preservation, Inc. Heritage Preservation 1012 14th St. Suite 1200 Washington, DC 20005 202-233-0800 fax 202-233-0807 www.heritagepreservation.org [email protected] Heritage Preservation receives funding from the National Park Service, Department of the Interior. However, the content and opinions included in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior. Table of Contents Introduction and Acknowledgements . i Executive Summary . 1 1. Heritage Health Index Development . 3 2. Methodology . 11 3. Characteristics of Collecting Institutions in the United States. 23 4. Condition of Collections. 27 5. Collections Environment . 51 6. Collections Storage . 57 7. Emergency Plannning and Security . 61 8. Preservation Staffing and Activitives . 67 9. Preservation Expenditures and Funding . 73 10. Intellectual Control and Assessment . 79 Appendices: A. Institutional Advisory Committee Members . A1 B. Working Group Members . B1 C. Heritage Preservation Board Members. C1 D. Sources Consulted in Identifying the Heritage Health Index Study Population. D1 E. Heritage Health Index Participants. E1 F. Heritage Health Index Survey Instrument, Instructions, and Frequently Asked Questions . F1 G. Selected Bibliography of Sources Consulted in Planning the Heritage Health Index. G1 H. N Values for Data Shown in Report Figures . H1 The Heritage Health Index Report i Introduction and Acknowledgements At this time a year ago, staff members of thou- Mary Chute, Schroeder Cherry, Mary Estelle sands of museums, libraries, and archives nation- Kenelly, Joyce Ray, Mamie Bittner, Eileen wide were breathing a sigh of relief as they fin- Maxwell, Christine Henry, and Elizabeth Lyons. -

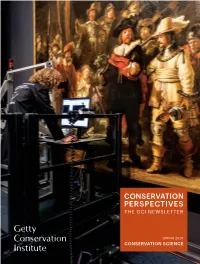

CONSERVATION PERSPECTIVES the Gci Newsletter

CONSERVATION PERSPECTIVES THE GCI NEWSLETTER SPRING 2020 CONSERVATION SCIENCE A Note from As this issue of Conservation Perspectives was being prepared, the world confronted the spread of coronavirus COVID-19, threatening the health and well-being of people across the globe. In mid-March, offices at the Getty the Director closed, as did businesses and institutions throughout California a few days later. Getty Conservation Institute staff began working from home, continuing—to the degree possible—to connect and engage with our conservation colleagues, without whose efforts we could not accomplish our own work. As we endeavor to carry on, all of us at the GCI hope that you, your family, and your friends, are healthy and well. What is abundantly clear as humanity navigates its way through this extraordinary and universal challenge is our critical reliance on science to guide us. Science seeks to provide the evidence upon which we can, collectively, make decisions on how best to protect ourselves. Science is essential. This, of course, is true in efforts to conserve and protect cultural heritage. For us at the GCI, the integration of art and science is embedded in our institutional DNA. From our earliest days, scientific research in the service of conservation has been a substantial component of our work, which has included improving under- standing of how heritage was created and how it has altered over time, as well as developing effective conservation strategies to preserve it for the future. For over three decades, GCI scientists have sought to harness advances in science and technology Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI Anna Flavin, Photo: to further our ability to preserve cultural heritage. -

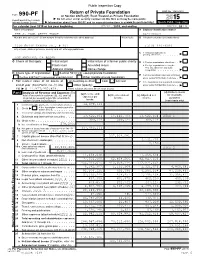

Attach to Your Tax Return. Department of the Treasury Attachment Sequence No

Public Inspection Copy Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990pf. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2015 or tax year beginning 07/01 , 2015, and ending 06/30, 20 16 Name of foundation A Employer identification number THE J. PAUL GETTY TRUST 95-1790021 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) 1200 GETTY CENTER DR., # 401 (310) 440-6040 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here LOS ANGELES, CA 90049 G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the Address change Name change 85% test, check here and attach computation H Check type of organization:X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here I Fair market value of all assets at J Accounting method: CashX Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination end of year (from Part II, col. -

Research Institute Grants

Getty Research Institute Grants Artistic Practice 2011/2012 Theme Year aT The GeTTY research insTiTuTe Artists mobilize a variety of intellectual, organizational, technological, and physical resources to create their work. This scholar year will delve into the ways in which artists receive, work with, and transmit ideas and images in various cultural traditions. At the Getty Research Institute, scholars will pay particular attention to the material manifestations of memory and imagination in the form of sketchbooks, notebooks, pattern books, and model books. How do notes, remarks, written and drawn observations reveal the creative process? In times and places where such media were not in use, what practices were developed to give ideas material form? In the ancient world, artists left traces of their creative process in a variety of media, but many questions remain for scholars in residence at the Getty Villa: What was the role of prototypes such as casts and models; what was their relationship to finished works? How were artists trained and workshops structured? How did techniques and styles travel? An interdisciplinary investigation among art historians and other specialists in the humanities will lead to a richer understanding of artistic practice. HoW To Apply Detailed instructions, application forms, complete theme statement and additional information are available online at www.getty.edu/foundation/apply Address inquiries to: Attn: (Type of Grant) The Getty Foundation 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 800 DeaDline los Angeles, CA 90049-1685 USA phone: 310 440.7374 nov 1 2010 E-mail: [email protected] Academy of fine arts, 1578. Research Library, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, California. -

J. Paul Getty Trust Press Clippings, 1954-2019 (Bulk 1983-2019), Undated

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8r215vp Online items available Finding aid for the J. Paul Getty Trust Press Clippings, 1954-2019 (bulk 1983-2019), undated Nancy Enneking, Rebecca Fenning, Kyle Morgan, and Jennifer Thompson Finding aid for the J. Paul Getty IA30017 1 Trust Press Clippings, 1954-2019 (bulk 1983-2019), undated Descriptive Summary Title: J. Paul Getty Trust press clippings Date (inclusive): 1954-2019, undated (bulk 1983-2019) Number: IA30017 Physical Description: 43.35 Linear Feet(55 boxes) Physical Description: 2.68 GB(1,954 files) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Institutional Records and Archives 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: The records comprise press clippings about the J. Paul Getty Trust, J. Paul Getty Museum, other Trust programs, and Getty family and associates, 1954-2019 (bulk 1983-2019) and undated. The records contain analog and digital files and document the extent to which the Getty was covered by various news and media outlets. Request Materials: To access physical materials at the Getty, go to the library catalog record for this collection and click "Request an Item." Click here for general library access policy . See the Administrative Information section of this finding aid for access restrictions specific to the records described below. Please note, some of the records may be stored off site; advanced notice is required for access to these materials. Language: Collection material is in English Administrative History The J. Paul Getty Trust's origins date to 1953, when J. -

Conservation Perspectives

CONSERVATION PERSPECTIVES FALL 2020 BUILT HERITAGE CONSERVATION EDUCATION AND TRAINING A Note from It is indisputable that education and training form the foundation of a profession. But as uncon- the Director troversial as that notion is, there is often less consensus within any given profession about what constitutes the best or most essential elements of that education. And in this historic moment of a worldwide pandemic, how—and in what ways—can education and training proceed and be effective? This edition of Conservation Perspectives examines how conservation education and training in built heritage have developed since the mid-twentieth century. Without question there has been exponential growth, providing opportunities for learning that did not exist for earlier generations. But with changing circumstances— including the pandemic and its aftereffects, as well as the reduced availability of resources—new issues and questions arise regarding what the field needs to do to advance in this area. We hope that we can provide some insights into where we need to go by looking back at where we’ve been. In our feature article, Jacqui Goddard, an architect who also teaches heritage conservation at the University of Sydney, charts the development of education in architectural conservation, which began in earnest in the latter half of the twen- tieth century. She notes that despite the rise of accreditation schemes, the divide Photo: Anna Flavin, GCI Anna Flavin, Photo: between individual professions and disciplines and conservation practice has yet to be fully bridged. In another article, my Getty Conservation Institute colleague Jeff Cody describes the GCI’s activities in built heritage conservation training and education from its earliest days to the present. -

Pacific Standard Time: Art in La

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contacts Ruder Finn Arts & Communications Counselors Rachel Bauch (310) 882-4013 / [email protected] Olivia Wareham (212) 583-2754 / [email protected] PACIFIC STANDARD TIME: ART IN L.A. 1945-1980 BEGINS THE COUNTDOWN TO ITS OCTOBER 2011 OPENING Bank of America Joins as Presenting Sponsor; Community Leaders and Foundations Expand the Ever-Growing Circle of Support New Partnerships, Exhibitions, Outreach Programs and Performance Art and Public Art Festival Are Announced for the Unprecedented Region-Wide Collaboration Los Angeles, CA, November 4, 2010 — Deborah Marrow, Interim President and CEO of the J. Paul Getty Trust, joined today with cultural and civic leaders from throughout Southern California to announce a host of new initiatives, partnerships, exhibitions and programs for the region-wide initiative Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945-1980, including presenting sponsorship from Bank of America. The first project of its kind, Pacific Standard Time has now begun the countdown to its October 2011 opening, when more than sixty cultural institutions throughout Southern California will come together to tell the story of the birth of the Los Angeles art scene and how it became a new force in the art world. This collaboration, the largest ever undertaken by cultural institutions in the region, will continue through April 2012. It has been initiated through grants totaling $10 million from the Getty Foundation. ―As we start marking the days toward the opening, the excitement about Pacific Standard Time continues to grow, and so does the project itself,‖ Deborah Marrow stated. ―What began as an effort to document the milestones in this region’s artistic history has expanded until it is now becoming a great creative landmark in itself. -

Executive Compensation Process

THE J. PAUL GETTY TRUST EMPLOYER IDENTIFICATION NO. 95-1790021 SENIOR MANAGEMENT COMPENSATION Updated March 3, 2015 The Role of the Board of Trustees in Overseeing Senior Management Compensation The full Board of Trustees establishes the terms of the President’s employment and compensation. The Compensation Committee, a standing committee composed of independent members of the Board of Trustees, approves the compensation of the President’s direct reports. Trustees of the J. Paul Getty Trust receive no compensation for their service but are reimbursed for travel expenses incurred in fulfilling their duties as members of the Board. In addition, Trustees are eligible to participate in a matching gift program providing matching gift funds to eligible qualified public charities on a four-to-one basis up to an annual maximum matching amount of $60,000. The J. Paul Getty Trust Senior Management Compensation Policy The goal of the Getty’s compensation process is to pay salaries that are competitive for comparable positions at organizations similar in activities and scope. The performance and compensation of the President and Chief Executive Officer is reviewed and set by the Board of Trustees in executive sessions in the absence of the President and CEO. Compensation decisions regarding direct reports to the President are recommended by the President and CEO to the Compensation Committee for approval. Program Directors and Vice Presidents are eligible to participate in a matching gifts program providing matching gift funds to eligible qualified public charities on a four-to-one basis up to an annual maximum matching amount of $32,000. The Compensation Committee reviews and compares compensation levels for the President and his direct reports with those reported for analogous positions at comparable organizations. -

Press Release

NEWS FROM THE GETTY news.getty.edu | [email protected] DATE: October 2, 2019 MEDIA CONTACT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Julie Jaskol Getty Communications (310) 440-7607 [email protected] DEBORAH MARROW LED GETTY FOUNDATION FOR 30 YEARS Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Trust LOS ANGELES – Deborah Marrow, who retired as director of the Getty Foundation at the end of last year after more than three decades of leadership in various roles at the Getty, including two stints as interim president, died early Tuesday morning. “No one has contributed more to the life and mission of the Getty than Deborah, and we will miss her deeply,” said James Cuno, president and CEO of the J. Paul Getty Trust. “She provided inspiring leadership in almost every aspect of the Getty, in roles including director of the Getty Foundation, acting director of the Getty Research Institute, and interim president of the Getty Trust. She brought clarity, vision, and selfless dedication to her work, and made loyal professional friends around the world.” As Foundation director, Marrow oversaw all grantmaking activity locally and worldwide in the areas of art history, conservation, and museums, as well as grants administration for all of the programs and departments of the J. Paul Getty Trust. The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 403 Tel: 310 440 7360 www.getty.edu Communications Department Los Angeles, CA 90049-1681 Fax: 310 440 7722 Cuno noted that one of Marrow’s proudest accomplishments was the creation of the Getty’s Multicultural Undergraduate Internship program, which over 27 years has dedicated over $14 million to support more than 3,400 internships at 160 local arts institutions in a pioneering effort to increase staff diversity in museums and visual arts organizations.