Nisbet Provincial Forest Integrated Forest Land Use Plan Background

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPATIAL DIFFUSION of ECONOMIC IMPACTS of INTEGRATED ETHANOL-CATTLE PRODUCTION COMPLEX in SASKATCHEWAN a Thesis Submitted To

SPATIAL DIFFUSION OF ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF INTEGRATED ETHANOL-CATTLE PRODUCTION COMPLEX IN SASKATCHEWAN A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Agricultural Economics University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon Emmanuel Chibanda Musaba O Copyright Emmanuel C. Musaba, 1996. All rights reserved. National Library Bibliotheque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Sewices services bibliographiques 395 WeIIington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada Your& vobrs ref6llBIlt8 Our & NomMhwm The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde me licence non exclusive licence dowing the exclusive pennettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, preter' distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfichelf2m, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format electronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriete du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protege cette these. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celIe-ci ne doivent Stre imprimes reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN College of Graduate Studies and Research SUMMARY OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial ilfihent b of the requirements for the DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY EMMANUEL CHLBANDA MUSABA Department of AgricuIturd Economics CoUege of Agriculture University of Saskatchewan Examining Committee: Dr. -

Foreign Missions of the Presbyterian Church in Canada

FOREIGN MISSIONS OF THE PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH IN CANADA THE INDIANS OF WESTERN CANADA JVtissionaries among the Indians. m Da I.OC ATroN Kkv. Georck 1*"lett, May, ihoo, Okanase. Hugh McKay, Junti, 1X84, Komul Lake W. S. Moore, B.A., May. 18S7. Lakesend. John McArthur, April 188S. Bird Tail. A. J. Mcl.EOD, B A., March, 1891, Regina. C. W. Whvte, 15 a., April, 1892, Crowstand. A. Wm. Lewis, B.D., December, 1892, Mistawasis. Miss Jen.nie Wninr (now Mrs \V. S. Moore) November, 18S6, Lakesend. Annie McLaren, September, 1S88. Birtle. Annie Frashr, October, 1888, Portaj^e la Prairie Mr. Alex. Skene, October, 1889, File Hills. Miss Martha Akmsironc, (now Mrs. Wrij^ht) May, 1890, Rolling River. Mr. W. J. Wright, August, i8gi, Rolling River. Mrs. !ean Leckie, August, 1891, Regina. Mr. Neil Gilmour, April, 1892, Birtle. Miss Matilda McLeod, December, 1892, Birtle. Makv S. Macintosh, December, 1892, Okanase. Sara Laidlaw, March, 1893, Portage la Prairie. Annie Cameron, August. 1893, Prince Albert. Laura MacLntosh, September, 1893, Mistawasis. Mr D. C. MUNRO, November, 1893, Regina. Miss Kate Gillespie, January, 1894, Crowstand. \lR. Peter C. Hunter, April, 1894, Pipestone Miss Flora Henderson, August. 1S94, Crowstand. I Mr. m. swartout, Alberni, Miss Bella L Johnston, 1893. Alberni, Retired op Galled kwdy bj Death, Thr Church lias received valuable and, in some cases, grat- uitous assistance from helpers w ho have been ablt to give tluir services only for a short time. For the purposes of this list it has been lliought bc'tter to include only those whose term of office has Deen longer than twelvt; months. -

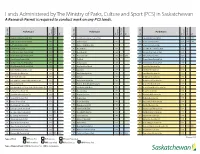

In Saskatchewan

Lands Administered by The Ministry of Parks, Culture and Sport (PCS) in Saskatchewan A Research Permit is required to conduct work on any PCS lands. Park Name Park Name Park Name Type of Park Type Year Designated Amendment Year of Park Type Year Designated Amendment Year of Park Type Year Designated Amendment Year HP Cannington Manor Provincial Park 1986 NE Saskatchewan Landing Provincial Park 1973 RP Crooked Lake Provincial Park 1986 PAA 2018 HP Cumberland House Provincial Park 1986 PR Anderson Island 1975 RP Danielson Provincial Park 1971 PAA 2018 HP Fort Carlton Provincial Park 1986 PR Bakken - Wright Bison Drive 1974 RP Echo Valley Provincial Park 1960 HP Fort Pitt Provincial Park 1986 PR Besant Midden 1974 RP Great Blue Heron Provincial Park 2013 HP Last Mountain House Provincial Park 1986 PR Brockelbank Hill 1992 RP Katepwa Point Provincial Park 1931 HP St. Victor Petroglyphs Provincial Park 1986 PR Christopher Lake 2000 PAA 2018 RP Pike Lake Provincial Park 1960 HP Steele Narrows Provincial Park 1986 PR Fort Black 1974 RP Rowan’s Ravine Provincial Park 1960 HP Touchwood Hills Post Provincial Park 1986 PR Fort Livingstone 1986 RP The Battlefords Provincial Park 1960 HP Wood Mountain Post Provincial Park 1986 PR Glen Ewen Burial Mound 1974 RS Amisk Lake Recreation Site 1986 HS Buffalo Rubbing Stone Historic Site 1986 PR Grasslands 1994 RS Arm River Recreation Site 1966 HS Chimney Coulee Historic Site 1986 PR Gray Archaeological Site 1986 RS Armit River Recreation Site 1986 HS Fort Pelly #1 Historic Site 1986 PR Gull Lake 1974 RS Beatty -

Directory of Cultural Services

Directory of Cultural Services For Prince Albert The Chronic Disease Network & Access Program Prince Albert Grand Council www.ehealth-north.sk.ca FREQUENTLY CALLED NUMBERS Emergency police, fire and ambulance: Ph: 911 Health Line 24 hour, free confidential health advice. Ph: 1-877-800-0002 Prince Albert City Police Victim’s Services Assist victims of crime, advocacy in the justice system for victims and counseling referrals. Ph: (306) 953-4357 Mobile Crisis Unit 24 hour crisis intervention and sexual assault program. Ph: (306) 764-1011 Victoria Hospital Emergency Health Care Ph: (306) 765-6000 Saskatchewan Health Cards Ph: 1-800-573-7377 MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES Prince Albert Mental Health Centre Inpatient and outpatient services. Free counseling with Saskatchewan Health Card Ph: (306) 765-6055 Canadian Mental Health Association Information about mental health issues. Ph: (306) 763-7747 The Nest (Drop in) 1322 Central Avenue (upstairs) Prince Albert, SK Hours: Mon – Fri, 8:30 – 3:30 PM Ph: (306) 763-8843 CULTURAL PROGRAMS Bernice Sayese Centre 1350 – 15th Avenue West Prince Albert, SK Services include nurse practitioner, seniors health, sexual health and addictions. Cultural programs include Leaving a Legacy (Youth Program); cultural programs in schools, recreation, karate, tipi teachings, pipe ceremonies and sweats. Hours: 9:00 – 9:00 PM Ph: (306) 763-9378 Prince Albert Indian and Métis Friendship Centre 1409 1st Avenue East Prince Albert, SK Services include a family worker, family wellness and cultural programs. Ph: (306) 764-3431 Holistic Wellness Centre Prince Albert Grand Council P.O. Box 2350 Prince Albert, SK Services include Resolution Health Support Workers and Elder services available upon request. -

Press Packet

One Arrow Equestrian One Arrow First Nation proudly announces Centre’s EAL Four Good Reasons Cover this Event 1) THE LEADING, First Nation COMMUNITY (nationally and internationally) to offer a personal growth and development program for every youth in the community to participate in, delivered through the school; a ground breaking commitment to the overall wellness to One Arrow First Nation. One Arrow EAL Directors will be on-site and available for interviews June 9th, at 11:30 a.m. 2) EAL RESEARCH PARTNERSHIP, AN EXPLORATORY STUDY OF THE CONTRIBUTION OF EQUINE ASSISTED LEARNING IN THE WELLBEING OF FIRST NATIONS PEOPLE LIVING ON RESERVE; The study is a collaborative effort between the One Arrow Equestrian Ctr (offers EAL Program), researchers at Brandon University (School of Health Studies), Almightyvoice Educational Centre (educational partnership and support), One Arrow First Nation of Saskatchewan (Chief and Council providing full support). Press Packet Researcher from BU, EAL Dirs, School Principal, and One Arrow First Nation Special Education Dir will be on-site and available for interviews, at 11:30 a.m. 3) ONE ARROW EQUESTRIAN CENTRE GRAND One Arrow Equestrian Centre OPENING and Inspire Direction Equine Assisted I.D.E.A.L. Program Learning Program (I.D.E.A.L.), first program of its kind, Inspire Direction Equine Assisted Learning designed to facilitate new skills for personal growth and Box 89, Domremy, SK S0K1G0 development: four teachers and their students will be Lawrence Gaudry – Executive Director, 306.423.5454 demonstrating different EAL exercises in the arena Koralie Gaudry – Program Director, 306.233.8826 www.oaecidealprogram.ca E-mail: [email protected] between 12:00 - 3:00 p.m. -

Perspectives of Saskatchewan Dakota/Lakota Elders on the Treaty Process Within Canada.” Please Read This Form Carefully, and Feel Free to Ask Questions You Might Have

Perspectives of Saskatchewan Dakota/Lakota Elders on the Treaty Process within Canada A Dissertation Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Interdisciplinary Studies University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon By Leo J. Omani © Leo J. Omani, copyright March, 2010. All rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of the thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis was completed. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain is not to be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Request for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis, in whole or part should be addressed to: Graduate Chair, Interdisciplinary Committee Interdisciplinary Studies Program College of Graduate Studies and Research University of Saskatchewan Room C180 Administration Building 105 Administration Place Saskatoon, Saskatchewan Canada S7N 5A2 i ABSTRACT This ethnographic dissertation study contains a total of six chapters. -

Diabetes Directory

Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory February 2015 A Directory of Diabetes Services and Contacts in Saskatchewan This Directory will help health care providers and the general public find diabetes contacts in each health region as well as in First Nations communities. The information in the Directory will be of value to new or long-term Saskatchewan residents who need to find out about diabetes services and resources, or health care providers looking for contact information for a client or for themselves. If you find information in the directory that needs to be corrected or edited, contact: Primary Health Services Branch Phone: (306) 787-0889 Fax : (306) 787-0890 E-mail: [email protected] Acknowledgement The Saskatchewan Ministry of Health acknowledges the efforts/work/contribution of the Saskatoon Health Region staff in compiling the Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory. www.saskatchewan.ca/live/health-and-healthy-living/health-topics-awareness-and- prevention/diseases-and-disorders/diabetes Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................... - 1 - SASKATCHEWAN HEALTH REGIONS MAP ............................................. - 3 - WHAT HEALTH REGION IS YOUR COMMUNITY IN? ................................................................................... - 3 - ATHABASCA HEALTH AUTHORITY ....................................................... - 4 - MAP ............................................................................................................................................... -

Ce Document Est Tiré Du Registre Aux Fins De La Loi Sur Le Patrimoine De L

This document was retrieved from the Ontario Heritage Act Register, which is accessible through the website of the Ontario Heritage Trust at www.heritagetrust.on.ca. Ce document est tiré du registre aux fins de la Loi sur le patrimoine de l’Ontario, accessible à partir du site Web de la Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien sur www.heritagetrust.on.ca. ~-----------------~ - •·- ·ref: CORPORATION OF THE TOWN OF OAKVILLE • 4 • BY-LAW 1993-58 A by-law to designate 85 Park ~venue as a property of historical and architectural value and interest THE COUNCIL ENACTS AS FOLLOWS: 1. The property municipally known as 85 Park Avenue is hereby designated as a property of historical and architectural value and interest pursuant to the • Ontario Heritage Act for reasons set out in Schedule ''A'' to this By-law. 2. The property designated by this By-law is the property described in Schedule ''B'' attached to this By-law. PASSED by the Council this 26th day of fVB.y, 1993. - • ,/ • . ,,,. .. ' . / ' l a;= I ~ ~-'- CLERK ' , , ~ ~ , ~ ·.. " #_,_. .. -----·-- ~ ~- ; - • * I~ - - .. ~- l._. --~. --- ,\..... .................... c ' - ........,"\... ... _.. .. .... ... - - ~....... ..... ..... --_ ..... •. -• .• -' -. • ... ... - - - .. .. Certified True Co y ~ : .- - ~ • • • • ' .,. s·cHBPUI,E ''A'' • The house at 85 Park Avenue was built in 1905 by George Hughes, soon after the Carson and Bacon Survey was drawn up for the land south of Lakeshore Road and between Mrs. Timothy Eaton's Raymar Estate and the Eighth Line. This ' land had originally been part of the Estate of the Reverend James Nisbet, who resided in the house at 10 Park Avenue. Reverend Nisbet ministered the Presbyterian congregation at Oakville and the Sixteen Village in the • 1850's. -

Doctrine of Discovery Research

Doctrine of Discovery Research Quotations from the A&P and WMS Annual Reports (and some additional sources*) which reflect a colonial attitude towards Indigenous people by The Presbyterian Church in Canada Prepared by: Bob Anger, Assistant Archivist, April 2018 * The quotes noted are essentially a large sampling. The list is not intended to be exhaustive or definitive; nor is it intended to reflect all aspects of the history of the Church’s interactions with Indigenous people. The A&P and WMS annual reports have been used as they reflect more or less official statements by the General Assembly and the WMS. Aside from these, there are a few quotes from Synod and Presbytery minutes, as well as quotes from the letters of Rev. James Nisbet which shed light on the early years. 1 Abbreviations PCC – The Presbyterian Church in Canada CPC – Canada Presbyterian Church FMC – Foreign Mission Committee HMC – Home Mission Committee HMB – Home Mission Board GBM – General Board of Mission WFMS – Woman’s Foreign Missionary Society WMS – Womens’ Missionary Society (Western Division) A&P – Acts and Proceedings of the General Assembly of The Presbyterian Church in Canada Note All quotations are from materials housed within The Presbyterian Church in Canada Archives. 2 Table of Contents 1866………………………………………………………………………………………….pg. 7 Quotes re: the first meeting between Rev. James Nisbet and the Indigenous people living along the North Saskatchewan River, near what is today Prince Albert, Saskatchewan (pg.7) 1867-1874...........................................................................................................................pg. 9 Quotes re: transfer of territory from the Hudson’s Bay Company to the Canadian Government (pg. 9) Quotes re: presumed inferiority of Indigenous culture and/or superiority of Euro-Canadian culture; use of terms such as “heathen” and “pagan” (pg. -

Akisq'nuk First Nation Registered 2018-04

?Akisq'nuk First Nation Registered 2018-04-06 Windermere British Columbia ?Esdilagh First Nation Registered 2017-11-17 Quesnel British Columbia Aamjiwnaang First Nation Registered 2012-01-01 Sarnia Ontario Abegweit First Nation Registered 2012-01-01 Scotchfort Prince Edward Island Acadia Registered 2012-12-18 Yarmouth Nova Scotia Acho Dene Koe First Nation Registered 2012-01-01 Fort Liard Northwest Territories Ahousaht Registered 2016-03-10 Ahousaht British Columbia Albany Registered 2017-01-31 Fort Albany Ontario Alderville First Nation Registered 2012-01-01 Roseneath Ontario Alexis Creek Registered 2016-06-03 Chilanko Forks British Columbia Algoma District School Board Registered 2015-09-11 Sault Ste. Marie Ontario Animakee Wa Zhing #37 Registered 2016-04-22 Kenora Ontario Animbiigoo Zaagi'igan Anishinaabek Registered 2017-03-02 Beardmore Ontario Anishinabe of Wauzhushk Onigum Registered 2016-01-22 Kenora Ontario Annapolis Valley Registered 2016-07-06 Cambridge Station 32 Nova Scotia Antelope Lake Regional Park Authority Registered 2012-01-01 Gull Lake Saskatchewan Aroland Registered 2017-03-02 Thunder Bay Ontario Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation Registered 2017-08-17 Fort Chipewyan Alberta Attawapiskat First Nation Registered 2019-05-09 Attawapiskat Ontario Atton's Lake Regional Park Authority Registered 2013-09-30 Saskatoon Saskatchewan Ausable Bayfield Conservation Authority Registered 2012-01-01 Exeter Ontario Barren Lands Registered 2012-01-01 Brochet Manitoba Barrows Community Council Registered 2015-11-03 Barrows Manitoba Bear -

George Flett, Native Presbyterian Missionary: "Old Philosopher"/"Rev 'D Gentleman1'

UNIVERSITY OF MANLTOBA/UNIVERSITY OF WINNIPEG JOINT MASTER'S PROGRAM GEORGE FLETT, NATIVE PRESBYTERIAN MISSIONARY: "OLD PHILOSOPHER"/"REV 'D GENTLEMAN1' THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE HISTORY DEPARTMENT IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY ALVINA BLOCK WINNIPEG, MANITOBA OCTOBER, 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 WeliiiStreet 395, nre Wellington OttawaON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seU reproduire, prêter, distriiuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic fomts. la forme de microfiche/fïlq de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantid extracts f?om it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES ***** COPYRIGHT PERMISSION PAGE GEORGE PfiETï, HATIVE PBESBYTERUH MISSIOî?AEY: "OLD PBZLOSOPfIE61'1/"BEV' D -" A ThesidPracticum submitted to the Facalty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fnlnllment of the reqairements of the degree of Permission has been granted to the Library of The University of Manitoba to lend or se11 copies of this thesWpracticum, to the National Library of Canada to microfilm this thesis and to lend or seil copies of the film, and to Dissertations Abstracts International to pubIish an abstract of this thesis/practicum. -

Sask Gazette, Part II, Feb 28, 1997

THE SASKATCHEWAN GAZETTE, FEBRUARY 28, 1997 PART II THE SASKATCHEWAN GAZETTE, FEBRUARY 28, 1997 REVISED REGULATIONS OF SASKATCHEWAN ERRATA NOTICE Pursuant to the authority given to me by section 12 of The Regulations Act, 1989, The Vital Statistics Regulations, as published in Part II of the Gazette on December 20, 1996, are corrected in the Appendix by striking out the first page of Form V.S.3, as printed on page 1115, and substituting the following: “ Form V.S. 3 Formulaire V.S. 3 [Subsection 10(1)] [Paragraphe 10(1)] Registration of Stillbirth Enregistrement de Mortinaissance ”. Dated at Regina, February 17, 1997. Lois Thacyk, Registrar of Regulations. 39 THE SASKATCHEWAN GAZETTE, FEBRUARY 28, 1997 ERRATA NOTICE Pursuant to the authority given to me by section 12 of The Regulations Act, 1989, The Urban Municipality Amendment Regulations, 1996, being Saskatchewan Regulations 99/96, as published in Part II of the Gazette on December 27, 1996, are corrected in subsection 7(2) by striking out FORM E.4 and FORM E.5 and substituting the following: “FORM E.4 Declaration of Appointed Officials [Section 7.4] I, __________________________, having been appointed to the office(s) of ____________ in the _____________________________________ of _________________________________ DO SOLEMNLY PROMISE AND DECLARE: 1. That I will truly, faithfully and impartially, to the best of my knowledge and ability, perform the duties of the said office(s); 2. That I have not received and will not receive any payment or reward, or promise of payment or reward, for the exercise of any corrupt practice or other undue execution of the said office(s); 3.