The Korean Onggi Potter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACTA KOR ANA VOL. 11, NO. 3, DECEMBER 2008: 235–269 BOOK REVIEWS Human Decency. by Kong Ji Yŏng. Translated by Bruce And

A C T A K O R A N A VOL. 11, NO. 3, DECEMBER 2008: 235–269 BOOK REVIEWS Human Decency . By Kong Ji Yŏng. Translated by Bruce and Ju-Chan Fulton. Published by Jimoondang as part of the Portable Library of Korean Literature, Short Fiction no. 24. Oftentimes, contemporary Korean fiction takes the reader, sometimes by force, down the dark memory lane of modern Korean history. Because so many works of contemporary Korean fiction are highly referential, the reader is often enticed to consider a text’s social and political background. While this is not a unique phenomenon to Korea—works of literature from all corners of the world often deal to greater or lesser extents with pressing political and social issues—it seems striking that Korean works of fiction so frequently draw the attention of their readers to the political and social realities being depicted, and do so in a manner that come at the expense of poetic expression. Kong Ji Yŏng’s short stories, “Human Decency” and “Dreams,” included in the collection Human Decency published by Jimoondang, are both highly referential texts. Since her works are so fraught with political and social references, this review will first examine the historical context in which Kong Ji Yŏng writes, and will then examine the stories in greater detail. In the collection of essays, Twentieth Century Korean Literature , it is noted that “an important strand of thought regarding literature in 1980s Korea was that it should interrogate social concerns and articulate communal values... the eighties were, in many ways, an era of causes. -

Great Food, Great Stories from Korea

GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIE FOOD, GREAT GREAT A Tableau of a Diamond Wedding Anniversary GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS This is a picture of an older couple from the 18th century repeating their wedding ceremony in celebration of their 60th anniversary. REGISTRATION NUMBER This painting vividly depicts a tableau in which their children offer up 11-1541000-001295-01 a cup of drink, wishing them health and longevity. The authorship of the painting is unknown, and the painting is currently housed in the National Museum of Korea. Designed to help foreigners understand Korean cuisine more easily and with greater accuracy, our <Korean Menu Guide> contains information on 154 Korean dishes in 10 languages. S <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Tokyo> introduces 34 excellent F Korean restaurants in the Greater Tokyo Area. ROM KOREA GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES FROM KOREA The Korean Food Foundation is a specialized GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES private organization that searches for new This book tells the many stories of Korean food, the rich flavors that have evolved generation dishes and conducts research on Korean cuisine after generation, meal after meal, for over several millennia on the Korean peninsula. in order to introduce Korean food and culinary A single dish usually leads to the creation of another through the expansion of time and space, FROM KOREA culture to the world, and support related making it impossible to count the exact number of dishes in the Korean cuisine. So, for this content development and marketing. <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Western Europe> (5 volumes in total) book, we have only included a selection of a hundred or so of the most representative. -

China in 50 Dishes

C H I N A I N 5 0 D I S H E S CHINA IN 50 DISHES Brought to you by CHINA IN 50 DISHES A 5,000 year-old food culture To declare a love of ‘Chinese food’ is a bit like remarking Chinese food Imported spices are generously used in the western areas you enjoy European cuisine. What does the latter mean? It experts have of Xinjiang and Gansu that sit on China’s ancient trade encompasses the pickle and rye diet of Scandinavia, the identified four routes with Europe, while yak fat and iron-rich offal are sauce-driven indulgences of French cuisine, the pastas of main schools of favoured by the nomadic farmers facing harsh climes on Italy, the pork heavy dishes of Bavaria as well as Irish stew Chinese cooking the Tibetan plains. and Spanish paella. Chinese cuisine is every bit as diverse termed the Four For a more handy simplification, Chinese food experts as the list above. “Great” Cuisines have identified four main schools of Chinese cooking of China – China, with its 1.4 billion people, has a topography as termed the Four “Great” Cuisines of China. They are Shandong, varied as the entire European continent and a comparable delineated by geographical location and comprise Sichuan, Jiangsu geographical scale. Its provinces and other administrative and Cantonese Shandong cuisine or lu cai , to represent northern cooking areas (together totalling more than 30) rival the European styles; Sichuan cuisine or chuan cai for the western Union’s membership in numerical terms. regions; Huaiyang cuisine to represent China’s eastern China’s current ‘continental’ scale was slowly pieced coast; and Cantonese cuisine or yue cai to represent the together through more than 5,000 years of feudal culinary traditions of the south. -

Effect of Rice (Oryza Sativa L.) Added to Meju (Korean Soybean Koji

Food and Nutrition Sciences, 2012, 3, 1167-1175 1167 http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/fns.2012.38154 Published Online August 2012 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/fns) Effect of Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Added to Meju (Korean Soybean Koji) Dough on Variation of Nutritional Ingredients and Bacterial Community Diversity in Doenjang (Korean Soybean Paste) Bo Young Jeon, Doo Hyun Park* Department of Biological Engineering, Seokyeong University, Seoul, South Korea. Email: *[email protected] Received May 21st, 2012; revised July 2nd, 2012; accepted July 9th, 2012 ABSTRACT In this study, effect of rice added to meju dough was evaluated based on the variation of nutritional ingredients and bacterial community diversity in finished doenjang. The ratio of rice added to meju dough (cooked and crushed soybean before fermentation) was 0, 0.2, and 0.4 based on dry weight. Free amino acids, minerals, polyphenol, and total pheno- lic compounds relatively decreased by addition of rice. However, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl free radical (DPPH) scavenging and ferric ion reduction activity was not influenced. Organic acids, which are fermentation metabolites, sig- nificantly increased in proportion to percentage balance of rice. Seven and four volatile compounds (VCs) were de- tected in doenjang prepared without and with rice, respectively, and contents of VCs were significantly lower in the rice-supplemented doenjang. Bacterial community diversity was significantly increased by addition of rice to meju dough. Rice alters chemical composition, fermentation products, and bacterial diversity, but does not downgrade the nature of doenjang. Keywords: Soybean Koji; Soybean Paste; Rice; Antioxidant Activity; Bacterial Community 1. Introduction on the basis of dry weight, and also contains physiologi- cally functional compounds such as polyphenol, total Doenjang is a Korean soy paste that has been prepared phenolic compounds, isoflavones, vitamin E, saponin, traditionally by long-term ripening of meju under high and anthocyanin [5-7]. -

Amy Howlett Amychowlett.Com Omitted – Just Add the Lemon Zest, Garlic, Thyme and Ground Coriander at the Stage of Sweating Down the Onions for the Pork Cheeks

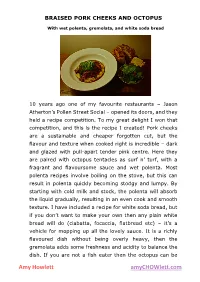

BRAISED PORK CHEEKS AND OCTOPUS With wet polenta, gremolata, and white soda bread 10 years ago one of my favourite restaurants – Jason Atherton’s Pollen Street Social – opened its doors, and they held a recipe competition. To my great delight I won that competition, and this is the recipe I created! Pork cheeks are a sustainable and cheaper forgotten cut, but the flavour and texture when cooked right is incredible – dark and glazed with pull-apart tender pink centre. Here they are paired with octopus tentacles as surf n’ turf, with a fragrant and flavoursome sauce and wet polenta. Most polenta recipes involve boiling on the stove, but this can result in polenta quickly becoming stodgy and lumpy. By starting with cold milk and stock, the polenta will absorb the liquid gradually, resulting in an even cook and smooth texture. I have included a recipe for white soda bread, but if you don’t want to make your own then any plain white bread will do (ciabatta, focaccia, flatbread etc) – it’s a vehicle for mopping up all the lovely sauce. It is a richly flavoured dish without being overly heavy, then the gremolata adds some freshness and acidity to balance the dish. If you are not a fish eater then the octopus can be Amy Howlett amyCHOWlett.com omitted – just add the lemon zest, garlic, thyme and ground coriander at the stage of sweating down the onions for the pork cheeks. Similarly, for any pescetarians the octopus quantity can be increased, cooking the onions and marinade ingredients from the pork cheek recipe before adding the marinated octopus. -

MAA AMC 8 C Summary of Results and Awards

A 2009 25th Annual M MAA AMC 8 C Summary of Results and Awards Learning Mathematics Through Selective Problem Solving amc.maa.org Examinations prepared by a subcommittee of the American Mathematics Competitions 8 and administered by the office of the Director ©2010 The Mathematical Association of America The American Mathematics Competitions are sponsored by The Mathematical Association of America and The Akamai Foundation Contributors: Academy of Applied Sciences American Mathematical Association of Two-Year Colleges American Mathematical Society American Statistical Association Art of Problem Solving Awesome Math Canada/USA Mathcamp Casualty Actuarial Society D.E. Shaw & Company IDEA Math Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences Math Zoom Academy Mu Alpha Theta National Council of Teachers of Mathematics Pi Mu Epsilon Society of Actuaries U.S.A. Math Talent Search W. H. Freeman and Company Wolfram Research Inc. Table Of COnTenTs 2010 USAMO Winners meet with John P. Holdren ............................................ 2 Report of the Director ..........................................................................................3 I. Introduction .................................................................................................... 3 II. General Results .............................................................................................. 3 III. Statistical Analysis of Results ......................................................................... 3 Table 1 - School & Student Registrations -

Shelf Life Validation of Marinated and Frozen Chicken Tenderloins by John Gregory Rehm a Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Facult

Shelf Life Validation of Marinated and Frozen Chicken Tenderloins by John Gregory Rehm A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Auburn, Alabama August 8, 2020 Approved by Dr. Christy Bratcher, Chair, Professor of Animal Science Dr. Jason Sawyer, Associate Professor of Animal Science Dr. Amit Morey, Assistant Professor of Poultry Science Abstract It is immensely important for producers and restaurants to know the shelf life of a meat product. If a consumer eats a product that is rancid it could impact a restaurant’s reputation. The objective of this study is to validate the shelf life of marinated and frozen chicken tenders. The treatments were the age of the chicken tender after harvest, which were 4 days of age (DA), DA5, DA6, DA7 and DA8. Spoilage organisms, pH and instrumental color (L*, a*, b*) were measured to assess the shelf life of bulk-packaged bags of chicken tenders. The microbial analysis analyzed the growth of aerobic, psychotrophic and lactobacilli bacteria. Each treatment contained 47.63 kg of chicken. Chicken was sampled fresh then tumbled in a marinade that contained water, salt, modified corn starch and monosodium glutamate. After marinating, the chicken tenders were sampled (0 hours) and the other remaining tenders were put into a blast freezer (-25ºC). After freezing, the chicken thawed in a cooler (2.2ºC) for 132 hours (h) and was sampled at 36h, 60h, 84h, 108h, 132h. After marinating the chicken tenders, each treatment decreased in the aerobic count and the psychotroph count except for DA4. -

Masonry Heating on the Internet

Volume 9 Number 1 Spring 1996 Masonry Heating on the Internet browsers should encounter minimal delays in MHA in Cyberspace downloading information. It is hoped that images will be storable at a high enough resolution to enable magazine by Norbert Senf publishers to get masonry heater images electronically HA voting members will soon find their for publication. No more waiting for your slides to be creations displayed on the Internet. The returned by magazine writers. executive has agreed to fund an MHA site on M The MHA page will also provide links to members who the World Wide Web that will tentatively have the have their own sites. These links are the essence of the address http://MHA-Net.org. Net surfers will initially Internet. By simply pointing to an item with a mouse find an interactive homepage that will have links to a and clicking the mouse button, you are taken almost membership list, an archive of back issues of MHA instantaneously to whichever computer the information News, as well as information about individual members. happens to reside on. It could be on the same machine, Your editor will be the “webmaster” administering the or on a machine on another continent. This feature is site. Members are each requested to send one high completely transparent to the user and is what has quality color photo, which will be scanned in as a high largely been responsible for the explosive growth of the resolution image that will be available online to any one “Web” in the last year. of the estimated 30,000,000 computers that currently Members who wish to set up their own sites will be able have Internet access. -

(RIA) for Proposed Residential Wood Heaters NSPS Revisions

Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA) for Proposed Residential Wood Heaters NSPS Revision Final Report January 2014 EPA-452/R-13-004 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Air and Regulation Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards Health and Environmental Impacts Division The EPA wishes to acknowledge the contributions of the Research Triangle Institute (RTI) International in the preparation of the industry profile and economic impact analysis, and EC/R, Inc. in the preparation of the emissions and cost estimates included in this report. CONTENTS Section Page Section 1 Executive Summary ............................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Analysis Summary ............................................................................................... 1-3 1.2 Organization of this Report .................................................................................. 1-5 Section 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 2-1 2.1 Background for Proposed Rule ............................................................................ 2-1 2.2 Room Heaters....................................................................................................... 2-1 2.3 Central Heaters: Hydronic Heaters and Forced-Air Furnaces ........................... 2-10 2.4 New Residential Masonry Heaters ..................................................................... 2-16 Section 3 Industry Profile ..................................................................................................... -

Wartime Forestry and the “Low Temperature Lifestyle” in Late Colonial Korea, 1937–1945

The Journal of Asian Studies Vol. 77, No. 2 (May) 2018: 333–350. © The Association for Asian Studies, Inc., 2018 doi:10.1017/S0021911817001371 Wartime Forestry and the “Low Temperature Lifestyle” in Late Colonial Korea, 1937–1945 DAVID FEDMAN This article examines the emergence in colonial Korea of a command economy for forestry products following the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45). It does so, first, by tracing the policy mechanisms through which the colonial state commandeered forest products, especially timber, firewood, and charcoal. Second, through an analysis of the wartime promotion of a “low temperature lifestyle,” it offers a thumbnail sketch of the lived experiences and corporeal consequences of state-led efforts to rationalize fuel consumption. Considered together, these lines of analysis offer insight into not only the ecological implications of war on the Korean landscape, but also the bodily privations that defined everyday life under total war—what might be called the “slow violence” of caloric control. Keywords: colonialism, energy, forestry, fuel, Japan, Korea, ondol, war HE OUTBREAK OF THE Second Sino-Japanese War in July 1937 precipitated a breakneck Tmobilization of Korea’s resources—military, industrial, and sylvan. Confronted with a newfound demand for war material, the Government-General of Korea (Chōsen Sōtokufu, hereafter GGK) ramped up the production of timber, charcoal, and a host of chemical components. To facilitate this push, the Major Industries Control Law was extended from the metropole to Korea, thereby tightening the colonial state’s grip on key war industries. A slate of laws thereafter restructured Korea’s heavy industrial base so as to meet the requirements of its so-called “national defense economy.” The colonial state likewise intensified its ideological efforts to enlist Korean subjects into service of the war effort. -

Protective Effect of Gochujang on Inflammation in a DSS-Induced Colitis Rat Model

foods Article Protective Effect of Gochujang on Inflammation in a DSS-Induced Colitis Rat Model Patience Mahoro 1,† , Hye-Jung Moon 1,†, Hee-Jong Yang 2 , Kyung-Ah Kim 3 and Youn-Soo Cha 1,4,* 1 Department of Food Science and Human Nutrition & Obesity Research Center, Jeonbuk National University, Jeonju 54896, Korea; [email protected] (P.M.); [email protected] (H.-J.M.) 2 Microbial Institute for Fermentation Industry (MIFI), Sunchang 56048, Korea; godfi[email protected] 3 Department of Food and Nutrition, Chungnam National University, Daejeon 34134, Korea; [email protected] 4 Obesity Research Center, Jeonbuk National University, Jeonju 54896, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-63-270-3822 † These authors contributed equally to the work. Abstract: Gochujang is a traditional Korean fermented soy-based spicy paste made of meju (fermented soybean), red pepper powder, glutinous rice, and salt. This study investigated the anti-inflammatory effects of Gochujang containing salt in DSS-induced colitis. Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats were partitioned into five groups: normal control, DSS control, DSS + salt, DSS + mesalamine, and DSS + Gochujang groups. They were tested for 14 days. Gochujang improved the disease activity index (DAI), colon weight/length ratio, and colon histomorphology, with outcomes similar to results of mesalamine administration. Moreover, Gochujang decreased the serum levels of IL-1β and IL-6 and inhibited TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β mRNA expression in the colon. Gochujang downregulated the expression of iNOS and COX-2 and decreased the activation of NF-κB in the colon. Gochujang induced significant modulation in gut microbiota by significantly increasing the number of Akkermansia muciniphila while decreasing the numbers of Enterococcus faecalis and Staphylococcus sciuri. -

HA 362/562 CERAMIC ARTS of KOREA – PLACENTA JARS, POTTERY WARS and TEA CULTURE Maya Stiller University of Kansas

HA 362/562 CERAMIC ARTS OF KOREA – PLACENTA JARS, POTTERY WARS AND TEA CULTURE Maya Stiller University of Kansas COURSE DESCRIPTION From ancient to modern times, people living on the Korean peninsula have used ceramics as utensils for storage and cooking, as well as for protection, decoration, and ritual performances. In this class, students will examine how the availability of appropriate materials, knowledge of production/firing technologies, consumer needs and intercultural relations affected the production of different types of ceramics such as Koryŏ celadon, Punch’ŏng stoneware, ceramics for the Japanese tea ceremony, blue-and-white porcelain, and Onggi ware (a specific type of earthenware made for the storage of Kimch’i and soybean paste). The class has two principal goals. The first is to develop visual analysis skills and critical vocabulary to discuss the material, style, and decoration techniques of Korean ceramics. By studying and comparing different types of ceramics, students will discover that ceramic traditions are an integral part of any society’s culture, and are closely connected with other types of cultural products such as painting, sculpture, lacquer, and metalware. Via an analysis of production methods, students will realize that the creation of a perfect ceramic piece requires the fruitful collaboration of dozens of artisans and extreme attention to detail. The second goal is to apply theoretical frameworks from art history, cultural studies, anthropology, history, and sociology to the analysis of Korean ceramic traditions to develop a deeper, intercultural understanding of their production. Drawing from theoretical works on issues such as the distinction between art and handicraft (Immanuel Kant), social capital (Pierre Bourdieu), “influence” (Michael Baxandall) and James Clifford’s “art-culture system,” students will not only discuss the function of ceramics in mundane and religious space but also explore aspects such as patronage, gender, collecting, and connoisseurship within and outside Korea.