How Many Transactions Per Second Can Bitcoin Really Handle ? Theoretically

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Big Data Velocity in Plain English

Big Data Velocity in Plain English John Ryan Data Warehouse Solution Architect Table of Contents The Requirement . 1 What’s the Problem? . .. 2 Components Needed . 3 Data Capture . 3 Transformation . 3 Storage and Analytics . 4 The Traditional Solution . 6 The NewSQL Based Solution . 7 NewSQL Advantage . 9 Thank You. 10 About the Author . 10 ii The Requirement The assumed requirement is the ability to capture, transform and analyse data at potentially massive velocity in real time. This involves capturing data from millions of customers or electronic sensors, and transforming and storing the results for real time analysis on dashboards. The solution must minimise latency — the delay between a real world event and it’s impact upon a dashboard, to under a second. Typical applications include: • Monitoring Machine Sensors: Using embedded sensors in industrial machines or vehicles — typically referred to as The Internet of Things (IoT) . For example Progressive Insurance use real time speed and vehicle braking data to help classify accident risk and deliver appropriate discounts. Similar technology is used by logistics giant FedEx which uses SenseAware technology to provide near real-time parcel tracking. • Fraud Detection: To assess the risk of credit card fraud prior to authorising or declining the transaction. This can be based upon a simple report of a lost or stolen card, or more likely, an analysis of aggregate spending behaviour, aligned with machine learning techniques. • Clickstream Analysis: Producing real time analysis of user web site clicks to dynamically deliver pages, recommended products or services, or deliver individually targeted advertising. Big Data: Velocity in Plain English eBook 1 What’s the Problem? The primary challenge for real time systems architects is the potentially massive throughput required which could exceed a million transactions per second. -

TRUST, but VERIFY: WHY the BLOCKCHAIN NEEDS the LAW Kevin Werbach†

TRUST, BUT VERIFY: WHY THE BLOCKCHAIN NEEDS THE LAW Kevin Werbach† ABSTRACT The blockchain could be the most consequential development in information technology since the Internet. Created to support the Bitcoin digital currency, the blockchain is actually something deeper: a novel solution to the age-old human problem of trust. Its potential is extraordinary. Yet, this approach may not promote trust at all without effective governance. Wholly divorced from legal enforcement, blockchain-based systems may be counterproductive or even dangerous. And they are less insulated from the law’s reach than it seems. The central question is not how to regulate blockchains but how blockchains regulate. They may supplement, complement, or substitute for legal enforcement. Excessive or premature application of rigid legal obligations will stymie innovation and forego opportunities to leverage technology to achieve public policy objectives. Blockchain developers and legal institutions can work together. Each must recognize the unique affordances of the other system. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15779/Z38H41JM9N © 2018 Kevin Werbach. † Associate Professor of Legal Studies and Business Ethics, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania. Email: [email protected]. Thanks to Dan Hunter for collaborating to develop the ideas that gave rise to this Article, and to Sarah Light, Patrick Murck, and participants in the 2017 Lastowka Cyberlaw Colloquium and 2016 TPRC Conference for comments on earlier drafts. 488 BERKELEY TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL [Vol. 33:487 -

PS Non-Standard Database Systems Overview

PS Non-Standard Database Systems Overview Daniel Kocher March 2019 is document gives a brief overview on three categories of non-standard database systems (DBS) in the context of this class. For each category, we provide you with a motivation, a discussion about the key properties, a list of commonly used implementations (proprietary and open-source/freely-available), and recommendation(s) for your project. For your convenience, we also recap some relevant terms (e.g., ACID, OLTP, ...). Terminology OLTP Online transaction processing. OLTP systems are highly optimized to process (1) short queries (operating only on a small portion of the database) and (2) small transac- tions (inserting/updating few tuples per relation). Typically, OLTP includes insertions, updates, and deletions. e main focus of OLTP systems is on low response time and high throughput (in terms of transactions per second). Databases in OLTP systems are highly normalized [5]. OLAP Online analytical processing. OLAP systems analyze complex data (usually from a data warehouse). Typically, queries in an OLAP system may run for a long time (as opposed to queries in OLTP systems) and the number of transactions is usually low. Fur- thermore, typical OLAP queries are read-only and touch a large portion of the database (e.g., scan or join large tables). e main focus of OLAP systems is on low response time. Databases in OLAP systems are oen de-normalized intentionally [5]. ACID Traditional relational database systems guarantee ACID properties: – Atomicity All or no operation(s) of a transaction are reected in the database. – Consistency Isolated execution of a transaction preserves consistency of the database. -

Performance Analysis of Blockchain Platforms

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones August 2018 Performance Analysis of Blockchain Platforms Pradip Singh Maharjan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Computer Sciences Commons Repository Citation Maharjan, Pradip Singh, "Performance Analysis of Blockchain Platforms" (2018). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 3367. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/14139888 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PERFORMANCE ANALYSIS OF BLOCKCHAIN PLATFORMS By Pradip S. Maharjan Bachelor of Computer Engineering Tribhuvan University Institute of Engineering, Pulchowk Campus, Nepal 2012 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science in Computer Science Department of Computer Science Howard R. Hughes College of Engineering The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas August 2018 c Pradip S. Maharjan, 2018 All Rights Reserved Thesis Approval The Graduate College The University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 4, 2018 This thesis prepared by Pradip S. -

Evaluating and Comparing Oracle Database Appliance Performance Updated for Oracle Database Appliance X8-2-HA

Evaluating and Comparing Oracle Database Appliance Performance Updated for Oracle Database Appliance X8-2-HA ORACLE WHITE PAPER | JANUARY 2020 DISCLAIMER The performance results in this paper are intended to give an estimate of the overall performance of the Oracle Database Appliance X8-2-HA system. The results are not a benchmark, and cannot be used to characterize the relative performance of Oracle Database Appliance systems from one generation to another, as the workload characteristics and other environmental factors including firmware, OS, and database patches, which includes Spectre/Meltdown fixes, will vary over time. For an accurate comparison to another platform, you should run the same tests, with the same OS (if applicable) and database versions, patch levels, etc. Do not rely on older tests or benchmark runs, as changes made to the underlying platform in the interim may substantially impact results. EVALUATING AND COMPARING ORACLE DATABASE APPLIANCE PERFORMANCE Table of Contents Introduction and Executive Summary 1 Audience 2 Objective 2 Oracle Database Appliance Deployment Architecture 3 Oracle Database Appliance Configuration Templates 3 What is Swingbench? 4 Swingbench Download and Setup 4 Configuring Oracle Database Appliance for Testing 5 Configuring Oracle Database Appliance System for Testing 5 Benchmark Setup 5 Database Setup 6 Schema Setup 6 Workload Setup and Execution 10 Benchmark Results 11 Workload Performance 11 Database and Operating System Statistics 12 Average CPU Busy 12 REDO Writes 13 Transaction Rate 13 Important Considerations for Performing the Benchmark 14 Conclusion 15 Appendix A Swingbench configuration files 16 Appendix B The loadgen.pl file 19 Appendix C The generate_awr.sh script 24 References 25 EVALUATING AND COMPARING ORACLE DATABASE APPLIANCE PERFORMANCE Introduction and Executive Summary Oracle Database Appliance X8-2-HA is a highly available Oracle database system. -

The Lightning Network - Deconstructed and Evaluated

The Lightning Network - Deconstructed and Evaluated Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Anti-Terrorist Financing (ATF) professionals, especially those working in the blockchain and cryptocurrency environment, may have heard of the second layer evolution of Bitcoin's blockchain - the Lightning Network, (LN). This exciting new and rapidly deploying technology offers innovative solutions to solve issues around the speed of transaction times using bitcoin currently, but expandable to other tokens. Potentially however, this technology raises regulatory concerns as it arguably makes, (based on current technical limitations), bitcoin transactions truly anonymous and untraceable, as opposed to its current status, where every single bitcoin can be traced all the way back to its coinbase transaction1 on the public blockchain. This article will break down the Lightning Network - analyzing how it works and how it compares to Bitcoin’s current system, the need for the technology, its money laundering (ML) and terrorist financing (TF) risks, and some thoughts on potential regulatory applications. Refresher on Blockchain Before diving into the Lightning Network, a brief refresher on how the blockchain works - specifically the Bitcoin blockchain (referred to as just “Bitcoin” with a capital “B” herein) - is required. For readers with no knowledge or those wishing to learn more about Bitcoin, Mastering Bitcoin by Andreas Antonopoulos2 is a must read, and for those wishing to make their knowledge official, the Cryptocurrency Certification Consortium, (C4) offers the Certified Bitcoin Professional (CBP) designation.3 Put simply, the blockchain is a growing list of records that can be visualized as a series of blocks linked by chains. Each block contains specific information - in Bitcoin’s case, a list of transactions and their data, which includes the time, date, amount, and the counterparties4 of each transaction. -

60-539: Emerging Non-Traditional Database Systems (Data Warehousing and Mining)

60-539: Emerging non-traditional database systems (Data Warehousing and Mining): sdb1 warehouse sdb2 sdb3 Dr. C.I. Ezeife School of Computer Science, University of Windsor, Canada. Email: [email protected] 60-539 Dr. C.I. Ezeife @c 2021 1 PART I (DATABASE MANAGEMENT SYSTEM OVERVIEW) DBMS (PART 1) OVERVIEW Components of a DBMS DBMS Data model Data Definition and Manipulation Language File Organization Techniques Query Optimization and Evaluation Facility Database Design and Tuning Transaction Processing Concurrency Control Database Security and Integrity Issues 60-539 Dr. C.I. Ezeife © 2021 2 DBMS OVERVIEW(What are?) What is a database? : It is a collection of data, typically describing the activities of one or more related organizations, e.g., a University, an airline reservation or a banking database. What is a DBMS?: A DBMS is a set of software for creating, querying, managing and keeping databases. Examples of DBMS’s are DB2, Informix, Sybase, Oracle, MYSQL, Microsoft Access (relational). Alternative to Databases: Storing all data for university, airline and banking information in separate files and writing separate program for each data file. What is a Data Warehouse?:A subject-oriented, historical, non- volatile database integrating a number of data sources. What is Data Mining?:Is data analysis for finding interesting trends or patterns in large dataset to guide decisions about future activities. 60-539 Dr. C.I. Ezeife © 2021 3 DBMS OVERVIEW(Evolution of Information Technology) 1960s and earlier: Primitive file processing: data are collected in files and manipulated with programs in Cobol and other languages. Disadv.: any change in storage structure of data requires changing the program (i.e., no logical or physical data independence). -

A Survey of Ledger Technology-Based Databases

future internet Article A Survey of Ledger Technology-Based Databases Dénes László Fekete 1 and Attila Kiss 1,2,* 1 Department of Information Systems, ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, 1117 Budapest, Hungary; [email protected] 2 Department of Informatics, J. Selye University, 945 01 Komárno, Slovakia * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The spread of crypto-currencies globally has led to blockchain technology receiving greater attention in recent times. This paper focuses more broadly on the uses of ledger databases as a traditional database manager. Ledger databases will be examined within the parameters of two categories. The first of these are Centralized Ledger Databases (CLD)-based Centralised Ledger Technology (CLT), of which LedgerDB will be discussed. The second of these are Permissioned Blockchain Technology-based Decentralised Ledger Technology (DLT) where Hyperledger Fabric, FalconDB, BlockchainDB, ChainifyDB, BigchainDB, and Blockchain Relational Database will be examined. The strengths and weaknesses of the reviewed technologies will be discussed, alongside a comparison of the mentioned technologies. Keywords: ledger technology; permissioned blockchain; centralised ledger database 1. Introduction Citation: Fekete, D.L.; Kiss, A. A In recent years, we have been witness to the rise of multiple new ledger technologies. Survey of Ledger Technology-Based Since Satosi Nakamoto wrote the Bitcoin white paper [1] in 2009, many different systems Databases. Future Internet 2021, 13, that endeavour to provide decentralization and trustless collaboration have been developed 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/ based on blockchain technology. Of late, a great amount of research and academia has been fi13080197 focused on the further development and reformation of the basis of blockchain in an attempt to solve the issues that continue to arise [2–4]. -

Bitcoin 2.0 – New Technologies and New Legal Impacts

October 16, 16, 2018 October RamdeRakesh – ProteumLLC Capital, –MinneJacob Lewis Bockius& Morgan, LLP ANDNEWIMPACTS LEGAL NEWTECHNOLOGIES BITCOIN2.0– © 2018 Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP Agenda • Introduction - A Brief Refresher on Bitcoin • Second Layer Solutions: – Lightning Network – Applicability of AML Laws – Extraterritoriality – Taxation – Potential Strategies • Digital Governance Strategies – Dash – Taxing and Spending – Ethereum and the DAO – EOS – On-Chain Dispute Ressolution • Business Assets on the Blockchain – Rakesh Ramde, Proteum Capital, LLC 2 INTRODUCTION AND REFRESHER ON BLOCKCHAIN A Blockchain Is: 1. A database, 2. that is distributed (not centralized), 3. whose data elements are immutable (unalterable), and 4. that is encrypted “At its simplest level, a blockchain is nothing much more than a fancy kind of database” - Blythe Masters, Digital Assets 4 Bitcoin Distributed Payment System • All participants (A-I) have sight of all transactions on A B the blockchain (and their C entire history) • Payments pass directly I between users, here A to F, D but are verified by other users (here, D, G, and I) • New transactions are H E broadcast to “miners” • When verified, the G F transaction is added to the (Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 2014 Q3) blockchain history 5 Advantages and Disadvantages Advantages: Disadvantages: • Accessibility • Slow transaction rate / (potentially) high cost • Redundancy • High Energy Cost • Passive access • Lack of Privacy 6 SECOND LAYER SOLUTIONS – A DISCUSSION OF LIGHTNING NETWORK Second Layer Solutions • Developers need a way to scale if Bitcoin is to have widespread adoption. One so-called “second layer” solution is “Lightning Network.” 8 Lightning Network • In Lightning, two peers make a single transaction on the blockchain, each locking some amount of bitcoin in a “channel.” • The two parties can then trade back and forth so long as the net balance never exceeds the channel balance. -

CSE 344 Final Examination Name

CSE 344 Final Examination Monday, December 10, 2018, 2:30-4:20 Name: Question Points Score 1 30 2 20 3 20 4 30 5 20 6 35 7 45 Total: 200 • This exam is CLOSED book and CLOSED devices. • You are allowed TWO, HAND-WRITTEN letter-size sheets with notes (both sides). • You have 110 minutes; • Answer the easy questions before you spend too much time on the more difficult ones. • Good luck! 1 CSE 344 Final Dec 10, 2018, 2:30-4:20 1 Relational Data Model 1. (30 points) You are now a Climate Scientist, and run simulations to predict future changes in the climate. Your job is to improve the simulator in order to improve the climate predictions. Every time you have a new version of the simulator, you run it, and it will generate a dataset where, for each year, it records the predicted temperature at each location of your simulated area. You analyze the results, improve the simulator, and repeat. As a good scientist, you keep the results of all simulations in a relation with the following schema: Sim(version, year, loc, temp) The data types of Version and year are integers; temp is a real number; and loc is a text. (a) (5 points) Write a SQL CREATE TABLE statement to create the Sim relation. Identify the key in Sim, and create the key in your SQL statement. Choose float and for the real number type and text for the text type. Page 2 CSE 344 Final Dec 10, 2018, 2:30-4:20 Sim(version, year, loc, temp) (b) (5 points) Simulation version 13 is wrong, due to a bug in the simulator. -

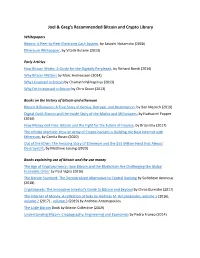

Joel & Greg's Recommended Bitcoin and Crypto Library

Joel & Greg’s Recommended Bitcoin and Crypto Library Whitepapers Bitcoin: A Peer‐to‐Peer Electronic Cash System, by Satoshi Nakamoto (2008) Ethereum Whitepaper, by Vitalik Buterin (2013) Early Articles How Bitcoin Works: A Guide for the Digitally Perplexed, by Richard Bondi (2014) Why Bitcoin Matters by Marc Andreessen (2014) Why I Invested in Bitcoin by Chamath Palihapitiya (2013) Why I’m Interested in Bitcoin by Chris Dixon (2013) Books on the history of bitcoin and ethereum Bitcoin Billionaires: A True Story of Genius, Betrayal, and Redemption, by Ben Mezrich (2019) Digital Gold: Bitcoin and the Inside Story of the Misfits and Millionaires, by Nathaniel Popper (2016) How Money Got Free: Bitcoin and the Fight for the Future of Finance, by Brian Eha (2017) The Infinite Machine: How an Army of Crypto‐hackers is Building the Next Internet with Ethereum, by Camila Russo (2020) Out of the Ether: The Amazing Story of Ethereum and the $55 Million Heist that Almost Destroyed It, by Matthew Leising (2020) Books explaining use of bitcoin and the use money The Age of Cryptocurrency: How Bitcoin and the Blockchain Are Challenging the Global Economic Order by Paul Vigna (2016) The Bitcoin Standard: The Decentralized Alternative to Central Banking by Saifedean Ammous (2018) Cryptoassets: The Innovative Investor's Guide to Bitcoin and Beyond by Chros Burniske (2017) The Internet of Money: A collection of talks by Andreas M. Antonopoulos, volume 1 (2016), volume 2 (2017) , volume 3 (2019) by Andreas Antonopoulos The Little Bitcoin Book by Bitcoin Collective -

Extending ACID Semantics to the File System

Extending ACID Semantics to the File System CHARLES P. WRIGHT IBM T. J. Watson Research Center RICHARD SPILLANE, GOPALAN SIVATHANU, and EREZ ZADOK Stony Brook University An organization’s data is often its most valuable asset, but today’s file systems provide few facilities to ensure its safety. Databases, on the other hand, have long provided transactions. Transactions are useful because they provide atomicity, consistency, isolation, and durability (ACID). Many applications could make use of these semantics, but databases have a wide variety of non-standard interfaces. For example, applications like mail servers currently perform elaborate error handling to ensure atomicity and consistency, because it is easier than using a DBMS. A transaction-oriented programming model eliminates complex error-handling code, because failed operations can simply be aborted without side effects. We have designed a file system that exports ACID transactions to user-level applications, while preserving the ubiquitous and convenient POSIX interface. In our prototype ACID file system, called Amino, updated applications can protect arbitrary sequences of system calls within a transaction. Unmodified applications operate without any changes, but each system call is transaction protected. We also built a recoverable memory library with support for nested transactions to allow applications to keep their in-memory data structures consistent with the file system. Our performance evaluation shows that ACID semantics can be added to applications with acceptable overheads.