Notes for a Writer: the Role of the Flute As Narrator in Jon Lord's to Notice Such Things

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medieninformation Vom 01.12.2008 (PDF)

Medieninformation vom 1. Dezember 2008 Sinfonieorchester Nota Bene trifft auf Deep Purple Legende Jon Lord Ein Musikspektakel, das unter die Haut geht 40 Jahre Crossover & Revolution: Am 10. und 12. Januar 2009 lässt es Deep Purple Legende Jon Lord auf den klassischen Konzertbühnen in Zürich und Luzern so richtig krachen. Zusammen mit dem Sinfonieorchester Nota Bene, einer internationalen ad hoc Rockband und Special Guest Steve Lee sorgt er für einen spannenden Mix aus Rock und Klassik. Im Mittelpunkt steht dabei sein «Concerto for Group and Orchestra», mit dem er 1969 die Musikwelt auf den Kopf stellte. Ergänzt wird das Programm mit Werken aus Lords Soloalben, die sein über 40-jähriges kompositorisches Schaffen widerspiegeln. Rockband meets Orchestra - ein Aufeinandertreffen, das unter die Haut geht. Konzertdaten Samstag, 10. Januar 2009 | 19.30 Uhr | Tonhalle Zürich | www.billettkasse.ch Montag, 12. Januar 2009 | 19.30 Uhr | Kultur- und Kongresszentrum Luzern | www.kkl-luzern.ch Jon Lord: Eine Rocklegende revolutioniert die klassische Musik 1969 stellte Jon Lord mit seinem Crossover-Projekt «Concerto for Group and Orchestra» die damalige Musikwelt auf den Kopf. Zusammen mit Deep Purple und dem Royal Philharmonic Orchestra brachte er das von ihm komponierte Werk im Herbst '69 in der Royal Albert Hall in London zur Uraufführung. Die Mitglieder von Deep Purple und die Musiker des Orchesters bewegten sich nicht nur musikalisch in zwei völlig verschiedenen Welten - die Kombination sorgte schon damals für viel Zündstoff und Power. Daran hat sich kaum etwas geändert. Auch heute noch treffen die zwei gegensätzlichen Musikstilrichtungen nur selten aufeinander. Und wenn sie es tun, entwickelt sich durch das Kräftespiel ein Feuerwerk subversiv-betörender Klangfarben. -

The Deep Purple Tributes

[% META title = 'The Deep Purple Discography' %] The Deep Purple Tributes Here we will try to keep a list of known Deep Purple tributes -- full CDs only. (Covers of individual tracks are listed elsewhere.) The list is still not complete, but hopefully it will be in the future. Funky Junction Plays a Tribute to Deep Purple UK 1973 Stereo Gold Award MER 373 [1LP] Purple Tracks Performed by Eric Bell (guitar), Brian Downey (drums), Dave Lennox (keyboards), Phil Lynott (bass) and Fireball Black Night Benny White (vocals). Strange Kind of Woman Hush Speed King The first known Purple tribute was recorded as early as 1972. An unknown, starving band named Thin Lizzy (which consisted of Bell, Downey & Lynott) were offered a lump sum of money to record some Deep Purple songs. (The album contains also a few non-DP tracks.) They did - with the help from two Irish guys. The album came out in early 1973. It wasn't a success. In February, Thin Lizzy had a top ten hit with a single of their own. Read more about it here. The Moscow Symphony Orchestra in Performance of the Music of Deep Purple Japan 1992 Zero Records XRCN-1022 [1CD] UK 1992 Cromwell Productions CPCD 018 [1CD] Purple Tracks Smoke on the Water Performed by the Moscow Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Constantine Krimets. Arranged by Stephen Space Truckin' Child in Time Reeve and Martin Riley. Produced by Bob Carruthers. Recorded live (in the studio with no audience) during Black Night April 1992. Lazy The Mule Pictures of Home No drums, no drum machine, no guitar - in fact, no rock instruments at all, just a symphony orchestra. -

Andre Jolivet's Fusion: Magical Music, Conventional Lyricism, and Japanese Influences Network Ot Create Concerto Pour Flute Et Piano and Sonate Pour Flute Et Piano

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones December 2016 Andre Jolivet's Fusion: Magical Music, Conventional Lyricism, and Japanese Influences Network ot Create Concerto Pour Flute et Piano and Sonate Pour Flute et Piano Kelly A. Collier University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Education Commons, and the Music Commons Repository Citation Collier, Kelly A., "Andre Jolivet's Fusion: Magical Music, Conventional Lyricism, and Japanese Influences Network to Create Concerto Pour Flute et Piano and Sonate Pour Flute et Piano" (2016). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2856. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/10083130 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANDRÉ JOLIVET’S FUSION: MAGICAL MUSIC, CONVENTIONAL LYRICISM, AND JAPANESE INFLUENCES NETWORK TO CREATE CONCERTO POUR FLÛTE ET PIANO AND SONATE POUR FLÛTE ET PIANO By Kelly A. Collier Bachelor of Music University of Nevada, Las Vegas 1999 Master of Music California State University, Long Beach 2001 Master of Music University of Nevada, Las Vegas 2016 A doctoral project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music College of Fine Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2016 Copyright 2016 Kelly A. -

Page 1 ED 333 726 AUTHOR TITLE INSTITUTION SPONS AGENCY

DOCUXENT REM= ED 333 726 FL 019 215 AUTHOR Weiser, Ernest V., Ed.; And Others TITLE Foreign Languages: Improving and Expanding Instruction. A Compendium of Teacher-Authored Activities for Foreign Language Classes. INSTITUTION Florida Atlantic Univ., Boca Raton. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education,Washington, DC. PUB DATE May 90 NOTE 295p. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use -Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Audiovisual Aids; *Classroom Communication; Classroom Techniques; *Communicative Competence (Languages); Inservice Teacher Education; Instructional Improvement; Intermediate Grades; *Lesson Plans; Secondary Education; *Second Lenguage Instruction; *Teacher Developed Materials ABSTRACT This collection of 98 lesson plans for foreign language instruction is the result of a series of eight Saturday workshops focusing on ways that language teachers can develop their own communicative activities for application in the classroom. The ).essons wert produced by 30 foreign language teachers, each of whom was required to write a brief report on how techniques and methods of instruction covered in each workshop session could be incorporated into lesson planning, and to create an actual lesson plan based on the report. Most were successfully implemented before inclusion in the collection. While the reports and plans are language-specific, the activities can be adapted for any modern language. Strategies on which the lessons are built include confidence-building, student-centered communication, use of audio-visual materials, development of oral/aural skills, increasing motivation, introducing and stimulating cultural awareness and appreciation, and evaluating skill development. Some lesson plans are illust.rated or contain reproducible materials. (MSE) illeft*********************A*********************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

RCM Clarinet Syllabus / 2014 Edition

FHMPRT396_Clarinet_Syllabi_RCM Strings Syllabi 14-05-22 2:23 PM Page 3 Cla rinet SYLLABUS EDITION Message from the President The Royal Conservatory of Music was founded in 1886 with the idea that a single institution could bind the people of a nation together with the common thread of shared musical experience. More than a century later, we continue to build and expand on this vision. Today, The Royal Conservatory is recognized in communities across North America for outstanding service to students, teachers, and parents, as well as strict adherence to high academic standards through a variety of activities—teaching, examining, publishing, research, and community outreach. Our students and teachers benefit from a curriculum based on more than 125 years of commitment to the highest pedagogical objectives. The strength of the curriculum is reinforced by the distinguished College of Examiners—a group of fine musicians and teachers who have been carefully selected from across Canada, the United States, and abroad for their demonstrated skill and professionalism. A rigorous examiner apprenticeship program, combined with regular evaluation procedures, ensures consistency and an examination experience of the highest quality for candidates. As you pursue your studies or teach others, you become not only an important partner with The Royal Conservatory in the development of creativity, discipline, and goal- setting, but also an active participant, experiencing the transcendent qualities of music itself. In a society where our day-to-day lives can become rote and routine, the human need to find self-fulfillment and to engage in creative activity has never been more necessary. The Royal Conservatory will continue to be an active partner and supporter in your musical journey of self-expression and self-discovery. -

50Th Annual Concerto Concert

SCHOOL OF ART | COLLEGE OF MUSICAL ARTS | CREATIVE WRITING | THEATRE & FILM BOWLING GREEN STATE UNIVERSITY 50th a n n u a l c o n c e r t o concert BOWLING GREEN STATE UNIVERSITY Summer Music Institute 2017 bgsu.edu/SMI featuring the SESSION ONE - June 11-16 bowling g r e e n Double Reed Strings philharmonia SESSION TWO - June 18-23 emily freeman brown, conductor Brass Recording Vocal Arts SESSION THREE - June 25-30 Musical Theatre saturday, february 25 Saxophone 2017 REGISTRATION OPENS FEBRUARY 1ST 8:00 p.m. For more information, visit BGSU.edu/SMI kobacker hall BELONG. STAND OUT. GO FAR. CHANGING LIVES FOR THE WORLD.TM congratulations to the w i n n e r s personnel of the 2016-2 017 Violin I Bass Trombone competition in music performance Alexandria Midcalf** Nicholas R. Young* Kyle McConnell* Brandi Main** Lindsay W. Diesing James Foster Teresa Bellamy** Adam Behrendt Jef Hlutke, bass Mary Solomon Stephen J. Wolf Morgan Decker, guest Ling Na Kao Cameron M. Morrissey Kurtis Parker Tuba Jianda Bai Flute/piccolo Diego Flores La Le Du Alaina Clarice* undergraduate - performance Nia Dewberry Samantha Tartamella Percussion/ Timpani Anna Eyink Michelle Whitmore Scott Charvet* Stephen Dubetz, clarinet Keisuke Kimura Jerin Fuller+ Elijah T omas Oboe/Cor Anglais Zachary Green+ Michelle Whitmore, flute Jana Zilova* Febe Harmon Violin II T omas Morris David Hirschfeld+ Honorable Mention: Samantha Tartamella, flute Sophia Schmitz Mayuri Yoshii Erin Reddick+ Bethany Holt Anthony Af ul Felix Reyes Zi-Ling Heah Jamie Maginnis Clarinet/Bass clarinet/ Harp graduate - performance Xiangyi Liu E-f at clarinet Michaela Natal Lindsay Watkins Lucas Gianini** Keyboard Kenneth Cox, flute Emily Topilow Hayden Giesseman Paul Shen Kyle J. -

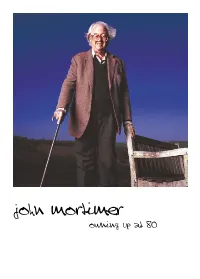

Imagine... John Mortimer

john mortimer owning up at 80 john mortimer owning up at 80 In the year he celebrates his 80th birthday, John Mortimer, the barrister turned author who became a household name with the creation of his popular drama Rumpole of the Bailey, is about to publish his latest book, Where There’s a Will. Imagine captures him pondering on life and offering advice to his children, grandchildren and in his own words “anyone who’ll listen”. John Mortimer’s wit and love of life shines through in this reflection on his life and career.The film eavesdrops on his 80th birthday celebrations, visits his childhood home – where he still lives today – and goes to his old law chambers.There are interviews with the people who know him best, including Richard Eyre, Jeremy Paxman, Kathy Lette, Leslie Phillips and Geoffrey Robertson QC. Imagine looks at the extraordinary influence Mortimer has had on the legal system in the UK.As a civil rights campaigner and defender par excellence in some of the most high-profile, inflammatory trials ever in the UK – such as the Oz trial and the Gay News case – he brought about fundamental changes at the heart of British law. His experience in the courts informs all of Mortimer’s writing, from plays, novels and articles to the infamous Rumpole of the Bailey, whose central character became a compelling mouthpiece for Mortimer’s liberal political views. Imagine looks at the great man of law, political campaigner, wit, gentleman, actor, ladies’ man and champagne socialist who captured the hearts of the British public.. -

And the Publication of James Kirkup's the Love That Dares to Speak Its

2009-2010 ALA MEMORIAL#1 2010 ALA Midwinter Meeting MEMORIAL RESOLUTION HONORING SIR JOHN CLIFFORD MORTIMER WHEREAS, John Mortimer, barrister and author, died on Friday, January 16, 2009, at the age of 85; and WHEREAS, Sir Jolm Clifford Mortimer, CBE, QC (21 April 1923-16 January 2009) on taking silk in 1966 undertook work in criminal law, particularly cases of obscenity charges, successfully defending publishers John Calder and Marion Boyars in their 1968 appeal against their conviction for publishing Hubert Selby, Jr.'s Last Exit to Brooklyn, and three years later, unsuccessfully, for Richard Handyside, the English publisher of The Little Red Schoolbook; and WHEREAS, In 1976 he defended Gay News editor Denis Lemon (Whitehouse v. Lemon) for the publication of James Kirkup's The Love that Dares to Speak its Name against charges of Blasphemous libel and Lemon's conviction was later overturned on appeal; and WHEREAS, His defense of Virgin Records in the 1977 obscenity hearing for their use of the word bollocks in the title of the Sex Pistols' album Never Mind The Bollocks, and the manager of the Nottingham branch of the Virgin record shop chain for the record's display in a window and its sale, led to the defendants being found not guilty; and WHEREAS, Mortimer may be best remembered for his character Horace Rwnpole, the barrister who defends those accused of crime in London's Old Bailey, using that character in Rumpole and the Reign of Terror published in 2006, to challenge the erosion of liberty in the name of national security; now, therefore, be it RESOLVED, That the American Library Association: 1. -

Jon Lord June 9 1941 – July 16 2012

Jon Lord June 9 1941 – July 16 2012 Founder member of Deep Purple, Jon Lord was born in Leicester. He began playing piano aged 6, studying classical music until leaving school at 17 to become a Solicitor’s clerk. Initially leaning towards the theatre, Jon moved to London in 1960 and trained at the Central School of Speech and Drama, winning a scholarship, and paying for food and lodgings by performing in pubs. In 1963 he broke away from the school with a group of teachers and other students to form the pioneering London Drama Centre. A year later, Jon “found himself“ in an R and B band called The Artwoods (fronted by Ronnie Wood’s brother, Art) where he remained until the summer of 1967. During this period, Jon became a much sought after session musician recording with the likes of Elton John, John Mayall, David Bowie, Jeff Beck and The Kinks (eg 'You Really Got Me'). In December 1967, Jon met guitarist Richie Blackmore and by early 1968 the pair had formed Deep Purple. The band would pioneer hard rock and go on to sell more than 100 million albums, play live to more than 10 million people, and were recognized in 1972 by The Guinness Book of World Records as “the loudest group in the world”. Deep Purple’s debut LP “Shades of Deep Purple” (1968) generated the American Top 5 smash hit “Hush”. In 1969, singer Ian Gillan and bassist Roger Glover joined and the band’s sound became heaver and more aggressive on “Deep Purple in Rock” (1970), where Jon developed a groundbreaking new way of amplifying the sound of the Hammond organ to match the distinctive sound of the electric guitar. -

Reviews: Baby It's Cold Outside

Reviews: Baby It’s Cold Outside Chris Pasin, trumpet; Patricia Dalton Fennell, vocals; Armen Donelian, piano; Ira Coleman, bass; Rich Syracuse, bass; Peter Einhorn, guitar; Jeff Siegel, drums Today’s Deep Roots Christmas Pick. December 20, 2017: Chris Pasin and Friends – ‘Baby It’s Cold Outside’ Deep Roots, David McGee Here’s a holiday outing that should satisfy traditionalists and adventurous spirits alike, a true rarity. Trumpeter/flugelhorn master Chris Pasin, whose resume includes several years touring as a soloist with Buddy Rich and backing giants on the order of Sinatra, Torme, Sarah Vaughn, Nancy Wilson, Ray Charles and Tony Bennett, as well crafting his own projects with some of New York’s finest jazz players, has brought some Gotham friends together, along with upstate New York-based vocalist Patricia Dalton Fennell (in a dual role as vocalist and producer), and given the holiday season the scintillating Baby It’s Cold Outside. For those more interested in new insights into seasonal warhorses, Pasin and friends offer a five-and-a- half-minute journey through “Santa Claus Is Coming to Town,” featuring discursive solos by Pasin on trumpet and pianist Armen Donelian, as well as a tasty drum-and-bass dialogue between Jeff Siegel and Ira Coleman, respectively, plus a couple of nice tempo changes for added texture. Similarly, “We Three Kings of Orient Are” is almost unrecognizable when Pasin soars into upper register impressionistic flurries before giving way to Donelian skittering across the keys and taking the melody line into uncharted waters over the course of six-and-a-half minutes. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

DEEP PURPLE “Whoosh!“ VÖ: 07.08.2020 (Earmusic / EDEL)

DEEP PURPLE “Whoosh!“ VÖ: 07.08.2020 (earMusic / EDEL) Erhältlich als limitiertes CD+DVD Mediabook (inkl. 1h Video "Roger Glover and Bob Ezrin in Conversation" und der erstmaligen Veröffentlichung der vollständigen Perfomance der Band beim Hellfest 2017) 2LP+DVD Edition , limitiertes Boxset und als digitale Version "Whoosh! " kann hier vorbestellt werden: https://deeppurple.lnk.to/WhooshPR DEEP PURPLE KÜNDIGEN IHR BRANDNEUES STUDIOALBUM AN “WHOOSH!” ERSCHEINT AM 7. AUGUST ÜBER earMUSIC “Another album?! Whoosh?!! Gordon Bennet!!!” ‘When the Deep Purple falls Over sleepy garden walls And the stars begin to twinkle In the night…’ Ian Gillan Deep Purple geben den Titel und das Veröffentlichungsdatum ihres brandneuen Studioalbums bekannt. "Whoosh! " ist der Nachfolger der weltweiten Chart-Erfolge "inFinite " (2017) und " NOW What?! " (2013). Nachdem kryptische Botschaften und Interviews des Sängers Ian Gillan im vergangenen Dezember Spannung und Spekulationen innerhalb der Fangemeinde ausgelöst haben, bestätigt die Band nun die Veröffentlichung ihres 21. Studioalbums am 7. August 2020 über earMUSIC . Für „ Whoosh !“ vereinen Deep Purple zum dritten Mal ihre Kräfte mit Produzent Bob Ezrin . Gemeinsam schrieben und nahmen sie in Nashville die neuen Songs auf und kreierten das bislang vielseitigste Werk ihrer Zusammenarbeit. Deep Purple lassen sich in ihrem Schaffen nicht eingrenzen, strecken sich in alle Richtungen aus und lassen ihrer Kreativität freien Lauf. "Putting the Deep back into Purple " wurde im Studio schnell zum inoffiziellen Motto. Bereits mit den ersten Songs war klar: Deep Purple und Bob Ezrin waren auf dem Weg ein neues Album zu schaffen, das die Grenzen der Zeit überschreitet, während sie sich mit ihrem Unmut über die aktuelle Situation der Welt an alle Generationen richten.