Ned Kelly Rides Again … and Again and Again

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classroom Ideas Available Classroom Ideas Available

Walker Books Classroom Ideas The Dog on the *Notes may be downloaded and printed for Tuckerbox regular classroom use only. Ph +61 2 9517 9577 Walker Books Australia Fax +61 2 9517 9997 Author: Corinne Fenton Locked Bag 22 Illustrator: Peter Gouldthorpe Newtown, N.S.W., 2042 ISBN: 9781922077462 These notes were created by Steve Spargo. ARRP: $16.95 For enquiries please contact: NZRRP: $18.99 [email protected] January 2013 Notes © 2012 Walker Books Australia Pty. Ltd. All Rights Reserved Outline: The legend that was to become The Dog on the Tuckerbox was created in the 1850s with a poem written by an author using the pen name of “Bowyang Yorke”. The poem was later amended and titled “Nine Miles from Gundagai” and was promoted as being written by Jack Moses. Its popularity spread but really caught Australians’ imaginations when it was released as a song in 1937 by Jack O’Hagan. The Dog on the Tuckerbox is the story of Australia’s early pioneers and their endeavours to open up land for white settlement. It is about the bullockies who transported supplies over makeshift trails – often encountering raised river levels or getting their wagons bogged in the muddy tracks. On these occasions, the bullocky (or teamster) would have to leave his wagon and load in search for help. The bullocky’s dog was left to guard the tuckerbox and his mas- ter’s belongings until the bullocky returned. This is a story about a dog called Lady and her devotion and loyalty to her master, a bullocky or teamster who goes by the name of Bill. -

Ned Kelly and the Kelly Gang

Ned Kelly and the Kelly Gang Use the words below to fill in the missing information. Glenrowan Inn life armour Ellen Quinn banks legend bushranger bravery unprotected outlawed surviving letter friends hanged awarded Australia’s most famous is Ned Kelly. Edward ‘Ned’ Kelly was born in Beveridge, Victoria in 1855. Ned’s mother was and his father was John ‘Red’ Kelly, an ex-convict. He was their eldest son of eight children. As a child, Ned rescued another boy from drowning. The boy’s family him a green silk sash in recognition of his . Red Kelly died when Ned was young and Ned was left to provide for the family. He worked cutting timber, breaking in horses, mustering cattle and fencing. During his teenage years, Ned got in trouble with the police. In 1878, Ned felt that his mother was put in prison wrongfully and he was being harassed by the police, so he went into the bush to hide. Together with his brother Dan and two others, Joe Byrne and Steve Hart, they became the Kelly Gang. The Gang was after killing three policemen at Stringybark Creek. This meant that they could be shot on sight by anybody at any time. For two years, the Gang robbed and avoided being captured. At the Jerilderie Bank robbery in 1879, with the help of Joe, Ned wrote a famous telling his side of the story. Many struggling small farmers of north-east Victoria felt they understood the Gang’s actions. It has been said that most of the takings from his famous bank robberies went to help his supporters, so many say Ned was an Australian Robin Hood. -

Ghosts of Ned Kelly: Peter Carey’S True History and the Myths That Haunt Us

Ghosts of Ned Kelly: Peter Carey’s True History and the myths that haunt us Marija Pericic Master of Arts School of Communication and Cultural Studies Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne November 2011 Submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts (by Thesis Only). Abstract Ned Kelly has been an emblem of Australian national identity for over 130 years. This thesis examines Peter Carey’s reimagination of the Kelly myth in True History of the Kelly Gang (2000). It considers our continued investment in Ned Kelly and what our interpretations of him reveal about Australian identity. The paper explores how Carey’s departure from the traditional Kelly reveals the underlying anxieties about Australianness and masculinity that existed at the time of the novel’s publication, a time during which Australia was reassessing its colonial history. The first chapter of the paper examines True History’s complication of cultural memory. It argues that by problematising Kelly’s Irish cultural memory, our own cultural memory of Kelly is similarly challenged. The second chapter examines Carey’s construction of Kelly’s Irishness more deeply. It argues that Carey’s Kelly is not the emblem of politicised Irishness based on resistance to imperial Britain common to Kelly narratives. Instead, he is less politically aware and also claims a transnational identity. The third chapter explores how Carey’s Kelly diverges from key aspects of the Australian heroic ideal he is used to represent: hetero-masculinity, mateship and heroic failure. Carey’s most striking divergence comes from his unsettling of gender and sexual codes. -

Stgd/Ned Kelly A4 . March

NED KELLY Study Guide by Robert Lewis and Geraldine Carrodus ED KELLY IS A RE-TELLING OF THE WELL-KNOWN STORY OF THE LAST AUSTRALIAN OUTLAW. BASED ON THE NOVEL OUR SUNSHINE BY ROBERT DREWE, THE FILM REPRESENTS ANOTHER CHAPTER IN NAUSTRALIA’S CONTINUING FASCINATION WITH THE ‘HERO’ OF GLENROWAN. The fi lm explores a range of themes The criminals are at large and are armed including justice, oppression, relation- and dangerous. People are encouraged ships, trust and betrayal, family loyalty, not to resist the criminals if they see the meaning of heroism and the nature them, but to report their whereabouts of guilt and innocence. It also offers an immediately to the nearest police sta- interesting perspective on the social tion. structure of rural Victoria in the nine- teenth century, and the ways in which • What are your reactions to this traditional Irish/English tensions and four police was searching for the known story? hatreds were played out in the Austral- criminals. The police were ambushed by • Who has your sympathy? ian colonies. the criminals and shot down when they • Why do you react in this way? tried to resist. Ned Kelly has the potential to be a very This ‘news flash’ is based on a real valuable resource for students of History, The three murdered police have all left event—the ambush of a party of four English, Australian Studies, Media and wives and children behind. policemen by the Kelly gang in 1878, at Film Studies, and Religious Education. Stringybark Creek. Ned Kelly killed three The gang was wanted for a previous of the police, while a fourth escaped. -

David Stratton's Stories of Australian Cinema

David Stratton’s Stories of Australian Cinema With thanks to the extraordinary filmmakers and actors who make these films possible. Presenter DAVID STRATTON Writer & Director SALLY AITKEN Producers JO-ANNE McGOWAN JENNIFER PEEDOM Executive Producer MANDY CHANG Director of Photography KEVIN SCOTT Editors ADRIAN ROSTIROLLA MARK MIDDIS KARIN STEININGER HILARY BALMOND Sound Design LIAM EGAN Composer CAITLIN YEO Line Producer JODI MADDOCKS Head of Arts MANDY CHANG Series Producer CLAUDE GONZALES Development Research & Writing ALEX BARRY Legals STEPHEN BOYLE SOPHIE GODDARD SC SALLY McCAUSLAND Production Manager JODIE PASSMORE Production Co-ordinator KATIE AMOS Researchers RACHEL ROBINSON CAMERON MANION Interview & Post Transcripts JESSICA IMMER Sound Recordists DAN MIAU LEO SULLIVAN DANE CODY NICK BATTERHAM Additional Photography JUDD OVERTON JUSTINE KERRIGAN STEPHEN STANDEN ASHLEIGH CARTER ROBB SHAW-VELZEN Drone Operators NICK ROBINSON JONATHAN HARDING Camera Assistants GERARD MAHER ROB TENCH MARK COLLINS DREW ENGLISH JOSHUA DANG SIMON WILLIAMS NICHOLAS EVERETT ANTHONY RILOCAPRO LUKE WHITMORE Hair & Makeup FERN MADDEN DIANE DUSTING NATALIE VINCETICH BELINDA MOORE Post Producers ALEX BARRY LISA MATTHEWS Assistant Editors WAYNE C BLAIR ANNIE ZHANG Archive Consultant MIRIAM KENTER Graphics Designer THE KINGDOM OF LUDD Production Accountant LEAH HALL Stills Photographers PETER ADAMS JAMIE BILLING MARIA BOYADGIS RAYMOND MAHER MARK ROGERS PETER TARASUIK Post Production Facility DEFINITION FILMS SYDNEY Head of Post Production DAVID GROSS Online Editor -

A STUDY GUIDE by Katy Marriner

© ATOM 2012 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN 978-1-74295-267-3 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Raising the Curtain is a three-part television series celebrating the history of Australian theatre. ANDREW SAW, DIRECTOR ANDREW UPTON Commissioned by Studio, the series tells the story of how Australia has entertained and been entertained. From the entrepreneurial risk-takers that brought the first Australian plays to life, to the struggle to define an Australian voice on the worldwide stage, Raising the Curtain is an in-depth exploration of all that has JULIA PETERS, EXECUTIVE PRODUCER ALINE JACQUES, SERIES PRODUCER made Australian theatre what it is today. students undertaking Drama, English, » NEIL ARMFIELD is a director of Curriculum links History, Media and Theatre Studies. theatre, film and opera. He was appointed an Officer of the Order Studying theatre history and current In completing the tasks, students will of Australia for service to the arts, trends, allows students to engage have demonstrated the ability to: nationally and internationally, as a with theatre culture and develop an - discuss the historical, social and director of theatre, opera and film, appreciation for theatre as an art form. cultural significance of Australian and as a promoter of innovative Raising the Curtain offers students theatre; Australian productions including an opportunity to study: the nature, - observe, experience and write Australian Indigenous drama. diversity and characteristics of theatre about Australian theatre in an » MICHELLE ARROW is a historian, as an art form; how a country’s theatre analytical, critical and reflective writer, teacher and television pre- reflects and shape a sense of na- manner; senter. -

E–Muster Central Coast Family History Society Inc

The Official Journal of the Central Coast Family History Society Inc. E–Muster Central Coast Family History Society Inc. December 2018 Issue 22 The Official Journal of the Central Coast Family History Society Inc. PATRONS Lucy Wicks, MP Federal Member for Robertson Jane Smith, Mayor- Central Coast Chris Holstein, Deputy Mayor- Central Coast Members of NSW & ACT Association of Family History Societies Inc. (State Body) Australian Federation of Family History Organisation (National Body) Federation of Family History Societies, United Kingdom (International Body) Associate Member, Royal Australian Historical Society of NSW. Executive: President: Paul Schipp Vice President: Marlene Bailey Secretary: Heather Yates Treasurer: Ken Clark Public Officer: Marlene Bailey Committee: Bennie Campbell, Lorna Cullen, Carol Evans, Rachel Legge, Belinda Mabbott, Trish Michael, Rosemary Wiltshire. RESEARCH CENTRE Building 4, 8 Russell Drysdale Street, EAST GOSFORD NSW 2250 Phone: 4324 5164 - Email [email protected] Open: Tues to Fri 9.30am-2.00pm; Thursday evening 6.00pm-9.30pm First and Fourth Saturday of the month 9.30am-12noon Research Centre Closed on Mondays for Administration MEETINGS First Saturday of each month from February to November Commencing at 1.00pm – doors open 12.00 noon Research Centre opens from 9.30am Venue: Gosford Lions Community Hall Rear of 8 Russell Drysdale Street, EAST GOSFORD NSW December 2018 – No: 22 The is the Official Journal of the Central Coast Family REGULAR FEATURES History Society Inc. as it was first Editorial ........................................................................... 4 published in April 1983. President’s Piece ......................................................... 4 New Members List ...................................................... 5 The new is Society Events and Information published to our website Speakers ......................................................................... -

PROGRAM 7Th - 9Th June 2019 7Th - June Weekend Long

SPECIAL EVENTS Friday 7 June BELLO POETRY SLAM 7:30-11:30pm Sponsored by Officeworks Saturday 8 June CRIME & MYSTERY WRITING 2:30-3:30pm & ‘Whodunnit? Who Wrote It?’ Six of Australia’s best crime/mystery authors Sunday 9 June explore this popular specialist genre in two 9:30-10:30pm featured panels Sunday 9 June IN CONVERSATION: KERRY O’BRIEN 6:30-8:00pm ‘A Life In Journalism’ Schools Program In the days leading up to the Festival weekend, the Schools Program will be placing a number of experienced authors into both primary and secondary schools in the Bellingen and Coffs Harbour regions. They will be presenting exciting interactive workshops that offer students a chance to explore new ways of writing and storytelling. This program is generously supported by Officeworks Ticket information Weekend Pass** $160 (Saturday Saturday Pass** $90 and Sunday) Sunday Pass** $90 (Please Note: Weekend Pass does NOT Single Event Pass $25 include Friday night Poetry Slam) Poetry Slam (Friday) $15 Morris Gleitzman - Special Kids & Parents session (Sunday, 9:30am) - Bellingen Readers & Writers Festival Adult $20 / Child* $5 (15 years and under) Gratefully acknowledges the support of ~ * Children under age 10 must be accompanied by an adult ** Concessions available for: Pensioner, Healthcare and Disability card holders, and Students – Available only for tickets purchased at the Waterfall PROGRAM Way Information Centre, Bellingen (evidence of status must be sighted) Weekend Pass concession $140 art+design: Walsh Pingala Saturday Pass & Sunday Pass concession each $80 All tickets available online at - • Trybooking - www.trybooking.com/458274 June Long Weekend Or in person from - • Waterfall Way Information Centre, Bellingen 7th - 9th June 2019 www.bellingenwritersfestival.com.au © 2019 www.bellingenwritersfestival.com.au Full festival program overleaf . -

Racial Tragedy, Australian History, and the New Australian Cinema: Fred Schepisi's the Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith Revisited

FILMHISTORIA Online Vol. 28, núms. 1-2 (2018) · ISSN: 2014-668X Racial Tragedy, Australian History, and the New Australian Cinema: Fred Schepisi’s The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith Revisited ROBERT J. CARDULLO University of Michigan Abstract The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1978) broke ground in its native country for dealing bluntly with one of the most tragic aspects of Australian history: the racist treatment of the aboriginal population. Adapted faithfully from the 1972 novel by Thomas Keneally, the film concerns a young man of mixed race in turn-of-the-century Australia who feels torn between the values and aspirations of white society, on the one hand, and his aboriginal roots, on the other, and who ultimately takes to violence against his perceived white oppressors. This essay re-views The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith from the following angles: its historical context; its place in the New Australian Cinema; its graphic violence; and the subsequent careers of the film’s director, Fred Schepisi, and its star, Tommy Lewis. Keywords: The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith; Fred Schepisi; Thomas Keneally; New Australian Cinema; racism and colonialism Prior to the late 1970s, Australia was something of a cinematic backwater. Occasionally, Hollywood and British production companies would turn up to use the country as a backdrop for films that ranged from the classic (On the Beach [1959]) to the egregious (Ned Kelly [1970], starring Mick Jagger). But the local movie scene, for the most part, was sleepy and unimaginative and very few Australian films traveled abroad. Then, without warning, Australia suddenly experienced an efflorescence of imaginative filmmaking, as movies such as Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), The Getting of Wisdom (1977), My Brilliant Career (1979), and Breaker Morant (1980) began to be shown all over the world. -

Exporting Truth from Aboriginal Australia

TOBY MIu.ER EXPORTING TRUTH FROM ABORIGINAL AUSTRAUA IPORTIONS OF OUR PAST BECOME PRESENT AGAIN, WHERE ONLY THE MELANCHOLY LIGHT OF ORIGIN SHINES' J don't think there can be any doubt that unnecessarily. Of course, we could look for Aborigines have been the most important the global trace of contemporary Australia Australian exporters of social theory and by a form of desperate content analysis. cultural production to the northern Adding up references to it in the Manhanan hemisphere over the past century. How fiction of Jay Mcinerney, for example: eight could one come to such a conclusion? in Bright Lights, Big City (986) if you count When Jock Given approached me to write the 1984 New York Post, none if you don't; this paper, he referred to a recent essay of four in Ransom (] 987); ten in Story ofMy Life mine. It began like this: 'When Australia (989) if you count each mention of Nell's, became modem, it ceased to be interesting'. three if you don't; and none in Brightness I ran the argument there that Aboriginal Falls (992). Or we could turn to the 1995 Australia had provided Europe with a 'Down Under' episode of The Stmpsons, in 'photographic negative' of itself. The which a State Department representative essence of the north, s~creted by the briefs the family on bilateral relations: 'As blllowtng engines and disputatious I'm sure you remember, in the late 1980s the parliaments of the modern, could be US experienced a short-lived infatuation secreted by examining 'the prediarnarue with Australian culture (this is accompanied realities of the Antipodean primordial' by a cartoon-slide of Paul Hogan as (Miller T 1994. -

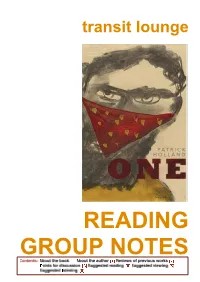

Reading Group Notes

transit lounge READING GROUP NOTES About the book The last bushrangers in Australian history, James and Patrick Kenniff, were at the height at their horse thieving operation at turn of the 20th century. In One, troops cannot pull the Kenniff Gang out of the ranges and plains of Western Queensland – the brothers know the terrain too well, and the locals are sympathetic to their escapades. When a policeman and a station manager go out on patrol from tiny Upper Warrego Station and disappear, Sergeant Nixon makes it his mission to pursue the gang, especially Jim Kenniff, who becomes for him an emblem of the violence that resides in the heart of the country. From the award-winning author of The Mary Smokes Boys, One is a novel of minimalist lyrical beauty that traverses the intersections between violence and love. It asks what right one man has to impose his will on another, and whether the written law can ever answer the law of the heart. About the author Patrick Holland is an Australian novelist and short story writer who grew up in outback Australia, later working as a horseman in the Maranoa district and as a ringer in the Top End. He has travelled widely throughout Asia, studying language and literature at Qingdao University and Beijing Foreign Studies University, and at the Ho Chi Minh Social Sciences University in Vietnam. His works include Navigatio [Transit Lounge 2014], shortlisted for Queensland Literary Awards - People's Choice Book of the Year 2015; The Darkest Little Room [Transit Lounge 2012], Pulp Curry Top 5 Crime Books of -

Twenty One Australian Bushrangers and Their Irish Connections

TWENTY ONE AUSTRALIAN BUSHRANGERS AND THEIR IRISH CONNECTIONS FATHER–JAMES KENNIFF FROM IRELAND–CAME FREE TO NSW. AFTER ONE BOOK WRITTEN ON PATRICK AND JAMES HARRY POWER CALLED (JNR) WERE CONVICTED FATHER – THOMAS SCOTT OF CATTLE STEALING AN ANGLICAN CLERGYMAN ALL THE FAMILY MOVED CAPTAIN MOONLITE FROM RATHFRILAND IN CO. THE BUSHRANGER TO QUEENSLAND BUT (1842-1880) DOWN WHERE ANDREW HARRY POWER THE BROTHERS WERE MARTIN CASH ANDREW GEORGE SCOTT WAS BORN. HARRY POWER TUTOR OF NED KELLY AGAIN CONVICTED. (1819-1891) BY PASSEY AND DEAN LATER THEY TOOK UP A MOTHER - JESSIE JEFFARIES 1991 LARGE GRAZING LEASE FROM THE SAME AREA. AT UPPER WARRIGO NEAR MARYBOROUGH IN SOUTHERN QUEELSLAND ANDREW TRAINED AS AN ENGINEER IN LONDON INSTEAD OF BECOMING A MOTHER – MARY CLERGYMAN AS HIS FATHER WISHED. THE FAMILY MOVED TO NEW (1810-1878) STAPLETON BORN NSW. PATRICK KENNIFF JAMES KENNIFF ZEALAND IN 1861, WHERE ANDREW BECAME AN OFFICER IN THE MAORI PRISON PHOTO (1863-1903) WARS AND WAS WOUNDED IN BOTH LEGS. HE WAS COURT MARSHALLED (1869-1940) BORN 1810 IN ENISCORTHY CO. WEXFORD AND GOT INTO TROUBLE IN 1828 FOR MALINGERING BUT WAS NOT CONVICTED. IN 1868 HE MOVED TO THE KENNIFF BROTHERS STARTED OFF AS CATTLE DUFFERS AND SPENT TIME FOR SHOOTING A RIVAL SUITOR AND TRANSPORTED TO NSW FOR 7 YEARS. MELBOURNE AND BEGAN HIS STUDIES FOR THE CLERGY. HE WAS SENT TO BORN HENRY JOHNSTON (JOHNSON) IN CO. WATERFORD C.1820. HE MIGRATED TO ENGLAND BUT GOT CAUGHT IN JAIL IN NSW. AFTER MOVING WITH THE REST OF THE FAMILY INCLUDING STEALING A SADDLE AND BRIDLE (SOME SAY IT WAS SHOES) AND TRANSPORTED TO VAN DIEMENS LAND FOR 7 HE WORKED OUT HIS SENTENCE BUT GOT INTO TROUBLE FOR BRANDING BROTHERS THOMAS AND JOHN TO QUEENSLAND, THEY RACED HORSES THE GOLDFIELDS BUT GOT MIXED UP IN A BANK SWINDLE AND WAS SENT TO PRISON.