THE OSCAR WILDE FORGERIES Was Wilde's Dada-Ist Nephew

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

«Es War Eng, Heiss Und Wild»

Samstag, 30. Januar 2016 27 100 JAHRE DADA Flüchtlinge als Geburtshelfer fürKunst Am 5. Februar feiertDada den 100. Geburtstag.Geboren wurde die einzige Kunstbewegung mit internationaler Strahlkraft, die vonder Schweiz ausgegangen ist, im Cabaret VoltaireimZür- cher Niederdorf.Hebammen waren Hugo Ball und seine Lebensgefährtin Emmy Hen- nings.Obwohl man sie den «Sterndes Cabaret Voltaire» nannte,stand die schillernde Künstlerin immer etwas im Schatten Hugo Balls.Ein Porträt zeigt auf, welche Rolledie Lite- ratin, Sängerin und Kabarettis- tin in den Anfangszeiten von Dada spielte. Seit zehn Jahren ist Adrian Notz Direktor des Cabaret Vol- taire, das um 2000 fast zu einer Apothekegeworden wäre, 2002 besetzt und 2004 wiedereröffnet wurde.ImInterview erzählt Notz, was ihn heute noch an Dada fasziniertund welche Atmosphärevor hundertJahren im Cabaret Voltaireherrschte. Diemeisten Dadaisten waren damals Kriegsflüchtlinge,die sich vordem Ersten Weltkrieg in die neutraleSchweiz gerettet hatten. Zu den wenigen Schwei- Bild: pd/Ay˛se Yava˛s zerDadaisten gehörte die Trog- Adrian Notz, der Direktordes Zürcher Cabaret Voltaire, im Holländerstübli, wo vor100 Jahren die Kunstbewegung Dada ihren Anfang nahm. nerin Sophie Taeuber-Arp.Auch der Dichter Arthur Cravan, der später die Literatur vonDada und des Surrealismus prägen sollte,hat eine Verbindung zur «Es war eng,heiss und wild» Ostschweiz: Er besuchte zwei Jahredas Institut Dr.Schmidt auf dem St.Galler Rosenberg. Am 5. Februar 1916 eröffnete im Zürcher Niederdorf das CabaretVoltaire. Es wardie Geburtsstunde vonDada. Dessen Auch heute gibt es Ost- heutiger Direktor Adrian Notz erklärt, wasDada mit Roman Signer,Lady Gaga und einer heiligen Kuhzutun hat. schweizer Kulturschaffende,die sich Dada verbunden fühlen. CHRISTINA GENOVA ren, die ganzeZeit da, da –also Zürichs sein wollte.Eskamen Bedeutung hatten. -

The Arthur Cravan Memorial Boxing Match

The Arthur Cravan Memorial Boxing Match Cast list Mina Loy Helena Stevens Jack Johnson Art Terry Fabian Lloyd (Arthur Cravan) Max Benezeth Dorian Hope Tam Dean Burn Announcer Richard Sanderson The Resonance Radio Orchestra: Tom Besley, Ben Drew, Dan Hayhurst, Alastair Leslie, Alex Ressel, Richard Thomas, Chris Weaver, Robin Warren and Jim Whelton. Live engineer: Mark Hornsby. Broadcast, webstreamed and recorded live before an audience at the Museum of Garden History, London, 16 October 2004. Written and directed by Ed Baxter. Music composed and arranged by Tom Besley, Ben Drew, Dan Hayhurst, Alastair Leslie, Alex Ressel, Richard Thomas, Chris Weaver, Robin Warren and Jim Whelton. A Resonance Radio Orchestra Production. SCENE 1 CRAVAN: Art follows life, leaving its disgusting trail like slime behind a snail. Garlic, garcon! Bring me garlic! ANNOUNCER: The Resonance Radio Orchestra presents “The Arthur Cravan Memorial Boxing Match.” In nineteen rounds. CRAVAN: World, do your worst. Your worst!… And yet, mesdames, messieurs, still one might crawl through a hole in the void, out through the splendid void. And one might leave no trail, nor even an empty shell. But now! – HOPE: What the --- ?! JOHNSON: Narrative emerges from a nomadic impulse, digression from something nearer home. For digression, like boredom, spews out of the gigantic conurbations, teaming cities ringed by barrows, by bazaars and by walls made of mud of the living flesh of other human beings. SCENE 2 LOY: I can still hear the music: shall I still be swept straight off my feet? Con man. Sailor of the pacific rim. Muleteer. Orange crate stand-up artiste. -

Hook to the Chin

PHYSICAL CULTURE AND SPORT STUDIES AND RESEARCH DOI: 10.2478/v10141-009-0005-1 Hook to the Chin Lev Kreft Department of Philosophy, Faculty of Arts – University of Ljubljana, Slovenia ABSTRACT Within historical avant-garde movements from the beginning of the 20 th century, a curious taste and fascination for boxing burst out, and developed later into the claim that art must become more similar to boxing, or to sport in general. This fascination with pugilism in the early stage of its popularity on the continent included such charismatic figures of the Parisian avant-garde as Arthur Cravan, who was Oscar Wilde’s nephew, a pretty good boxer and an unpredictable organizer of proto-dada outrages and scandals. After WWI, the zenith of artists’ and intellectuals’ love for boxing was reached in Weimar Germany. One of the well known examples connecting boxing with art was Bertolt Brecht with his statement that we need more good sport in theatre. His and other German avant-garde artists' admiration for boxing included the German boxing star May Schmeling, who was, at least until he lost his defending championship match against Joe Louis, an icon of the Nazis as well. Quite contrary to some later approaches in philosophy of sport, which compared sport with an elite art institution, Brecht’s fascination with boxing took its anti-elitist and anti-institutional capacities as an example for art’s renewal. To examine why and how Brecht included boxing in his theatre and his theory of theatre, we have to take into account two pairs of phenomena: sport vs. -

Tristan Tzara

DADA Dada and dadaism History of Dada, bibliography of dadaism, distribution of Dada documents International Dada Archive The gateway to the International Dada Archive of the University of Iowa Libraries. A great resource for information about artists and writers of the Dada movement DaDa Online A source for information about the art, literature and development of the European Dada movement Small Time Neumerz Dada Society in Chicago Mital-U Dada-Situationist, an independent record-label for individual music Tristan Tzara on Dadaism Excerpts from “Dada Manifesto” [1918] and “Lecture on Dada” [1922] Dadart The site provides information about history of Dada movement, artists, and an bibliography Cut and Paste The art of photomontages, including works by Heartfield, Höch, Hausmann and Schwitters John Heartfield The life and work of the photomontage artist Hannah Hoch A collection of photo montages created by Hannah Hoch Women Artists–Dada and Surrealism An excerpted chapter from Margaret Barlow’s illustrated book Women Artists Helios A beginner’s guide to Dada Merzheft German Dada, in German Dada and Surrealist Film A Bibliography of Materials in the UC Berkeley Library La Typographie Dada D.E.A. memoir in French by Breuil Eddie New York Avant-Garde, 1913-1929 New York Dada and the Armory Show including images and bibliography Excentriques A biography of Arthur Cravan in French Tristan Tzara, a Biography Excerpt from François Buot’s biography of Tzara,L’homme qui inventa la Révolution Dada Tristan Tzara A selection of links on Tzara, founder of the Dada movement Mina Loy’s lunar odyssey An online collection of Mina Loy’s life and work Erik Satie The homepage of Satie 391 Experimental art inspired by Picabia’s Dada periodical 391, with articles on Picabia, Duchamp, Ball and others Man Ray Internet site officially authorized by the Man Ray Trust to offer reproductions of the Man Ray artworks. -

Genius Is Nothing but an Extravagant Manifestation of the Body. — Arthur Cravan, 1914

1 ........................................... The Baroness and Neurasthenic Art History Genius is nothing but an extravagant manifestation of the body. — Arthur Cravan, 1914 Some people think the women are the cause of [artistic] modernism, whatever that is. — New York Evening Sun, 1917 I hear “New York” has gone mad about “Dada,” and that the most exotic and worthless review is being concocted by Man Ray and Duchamp. What next! This is worse than The Baroness. By the way I like the way the discovery has suddenly been made that she has all along been, unconsciously, a Dadaist. I cannot figure out just what Dadaism is beyond an insane jumble of the four winds, the six senses, and plum pudding. But if the Baroness is to be a keystone for it,—then I think I can possibly know when it is coming and avoid it. — Hart Crane, c. 1920 Paris has had Dada for five years, and we have had Else von Freytag-Loringhoven for quite two years. But great minds think alike and great natural truths force themselves into cognition at vastly separated spots. In Else von Freytag-Loringhoven Paris is mystically united [with] New York. — John Rodker, 1920 My mind is one rebellion. Permit me, oh permit me to rebel! — Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, c. 19251 In a 1921 letter from Man Ray, New York artist, to Tristan Tzara, the Romanian poet who had spearheaded the spread of Dada to Paris, the “shit” of Dada being sent across the sea (“merdelamerdelamerdela . .”) is illustrated by the naked body of German expatriate the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (see fig. -

Lacing up the Gloves: Women, Boxing and Modernity Irene Gammel Ryerson University, Toronto

Lacing Up the Gloves: Women, Boxing and Modernity Irene Gammel Ryerson University, Toronto Abstract This article explores women’s early twentieth-century engagement with boxing as a means of expressing the fragmentations and contradictions of modern life. Equally drawn to and repelled by the visceral agonism of the sport, female artists and writers of the First World War and post- war era appropriated the boxer’s virile body in written and visual autobiographies, effectively breaching male territory and anticipating contemporary notions of female autonomy and self- realization. Whether by reversing the gaze of desire as a ringside spectator or inhabiting the physical sublime of boxing itself, artists such as Djuna Barnes, Vicki Baum, Mina Loy and Clara Bow enlisted the tropes, metaphors and physicality of boxing to fashion a new understanding of their evolving status and identity within a changing social milieu. At the same time, their corporeal and textual self-inscriptions were used to stage their own exclusion from the sport and the realm of male agency and power. Ultimately, while modernist women employ boxing to signal a radical break with the past, or a reinvention of self, they also use it to stage the violence and trauma of the era, aware of limits and vulnerabilities. Keywords: boxing, women, modernity, self-representation, gender 1 Lacing Up the Gloves: Women, Boxing and Modernity No man, even if he had earlier been the biggest Don Juan, still risks it in this day and age to approach a lady on the street. The reason: the woman is beginning to box! - German boxing promoter Walter Rothenburg, 19211 Following Spinoza, the body is regarded as neither a locus for a consciousness nor an organically determined entity; it is understood more in terms of what it can do, the things it can perform, the linkages it establishes, the transformations and becomings it undergoes, and the machinic connections it forms with other bodies, what it can link with, how it can proliferate its other capacities – a rare, affirmative understanding of the body. -

Web-FINAL The-SEEN Issue 05 Working For-Output.Indd

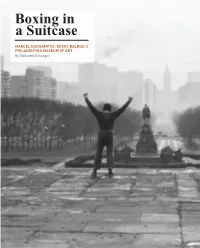

Boxing in a Suitcase MARCEL DUCHAMP VS. ROCKY BALBOA // PHILADELPHIA MUSEUM OF ART By Guillaume Désanges [ THE SEEN ] “Genius is nothing but an extraordinary manifestation of the body.” —ARTHUR CRAVAN, 1914 This text applies a Duchampian methodology: that of imaginative chance, Rather, the exhibition suggested that through the mere anticipation of or how meaning is created by coincidence. ———————————— searching, the viewer would be placed in the position of finding something. ————————— In 2011, an exhibition at the Städtische Galerie im Indeed, this could be the lesson revealed by Duchamp’s art practice—to Lenbachhaus in Munich, Germany was based on Marcel Duchamp’s brief launch random hypotheses, and appropriate what emerges from its results. stay in the city in 1912. The show proposed to reveal, by way of extensive ————————————————————— Let us approach this research, the essential matrix of the artist’s work. Could the achievement of theory from another side. such a proposition be proved either true or false? This was not the question. [ MARCEL DUCHAMP VS. ROCKY BALBOA | 49 ] [ 50 | THE SEEN ] ASCENDING AND DESCENDING THE STAIRCASE. The city of Philadelphia, as a site, is a place opposite. While positioned out of the view of of the sport—but also Pablo Picasso, Georges of pilgrimage for at least two reasons; the the camera, this piece and others remain within Braque, Man Ray, and Pierre Bonnard. For the first is Rocky Balboa—the anti-hero boxer, the context of the film—hidden just beyond the Dada movement especially, whom Duchamp whose persona was brought to life by Sylvester site where the boxer stands, defiantly throwing was part of, boxing represented a jubilant, yet Stallone—and the other is Marcel Duchamp, at his two arms in the air. -

AMELIA JONES “'Women' in Dada: Elsa, Rrose, and Charlie”

AMELIA JONES “’Women’ in Dada: Elsa, Rrose, and Charlie” From Naomi Sawelson-Gorse, Women in Dada:Essays on Sex, Gender, and Identity (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998): 142-172 In his 1918 Dada manifesto, Tristan Tzara stated the sources of “Dadaist Disgust”: “Morality is an injection of chocolate into the veins of all men....I proclaim the opposition of all cosmic faculties to [sentimentality,] this gonorrhea of a putrid sun issued from the factories of philosophical thought.... Every product of disgust capable of becoming a negation of the family is Dada.”1 The dadaists were antagonistic toward what they perceived as the loss of European cultural vitality (through the “putrid sun” of sentimentality in prewar art and thought) and the hypocritical bourgeois morality and family values that had supported the nationalism culminating in World War I.2 Conversely, in Hugo Ball's words, Dada “drives toward the in- dwelling, all-connecting life nerve,” reconnecting art with the class and national conflicts informing life in the world.”3 Dada thus performed itself as radically challenging the apoliticism of European modernism as well as the debased, sentimentalized culture of the bourgeoisie through the destruction of the boundaries separating the aesthetic from life itself. But Dada has paradoxically been historicized and institutionalized as “art,” even while it has also been privileged for its attempt to explode the nineteenth-century romanticism of Charles Baudelaire's “art for art's sake.”4 Moving against the grain of most art historical accounts of Dada, which tend to focus on and fetishize the objects produced by those associated with Dada, 5 I explore here what I call the performativity of Dada: its opening up of artistic production to the vicissitudes of reception such that the process of making meaning is itself marked as a political-and, specifically, gendered-act. -

Dada, Cyborgs and the New Woman in New York

3 Dada, Cyborgs and the New Woman in New York Who is she, where is she, what is she – this ‘modern woman’ that people are always talking about? Is there any such creature? Does she look any different looks or talk any different words or think any different thoughts from the late Cleopatra or Mary Queen of Scots or Mrs Browning? Some people think the women are the cause of modernism whatever that is. But then, some people think woman is to blame for everything they don’t like or don’t understand. Cher- chez la femme is man-made advice, of course. (New York Evening Sun, 13 February 1917)1 New York in 1917, particularly with the first Independents Exhibition and the events surrounding it, was in the grip not just of an American flowering of modernist innovation, but of the specific manifestation of New York Dada. The term New York Dada is a retrospective appellation emerging from Zurich Dada and from 1920s popular press reflections on New York modernism; it suggests a more coherent movement than was understood by those living and working in this arena at the time. The many individuals participating in or on the margins of New York Dada included French expatriates such as Francis Picabia and Marcel Duchamp and Americans such as Alfred Steiglitz and Man Ray. Even Ezra Pound was touched by New York Dada, writing two poems for The Little Review in 1921 that explored the interchange between one of its most visible figures, Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, and William Carlos Williams.2 It is not incidental that while the First World War in Europe raged, disturbing the boundaries of ‘natural’ identity and enacting a machinic destruction of cultural and human life, artists and writers in New York 85 A. -

L'exposition Des Indépendants Par Arthur Cravan

jfumêro Special 3 ANNÉE Ν" 4 Mars-Avril 1914 ENANT REVUE LITTÉRAIRE DIRECTEUR : Arthur Cravan PARIS — 29, Avenue de l'Observatoire, 29 — PARIS Le Numéro : 2S Centimes SOMMAIRE L'Exposition des Indépendants par Arthur Cravan L'EXPOSITION DES INDÉPENDANTS Les peintres, — ils sont 2 ou 3 en France, — ont vrai- ment peu de représentations, et je me figure facilement leur état de mort, quand, durant de longs mois, ils ne paraissent plus en public. C'est une des raisons pourquoi je viens grossir le nombre des spectateurs qui se rendent au Salon des îndépen- dants; bien que la meilleure soit encore le profond dégoût de la peinture que j'emporterai en sortant de l'exposition, et c est un sentiment que le plus souvent on ne peut jamais assez développer. Mon Dieu, que les temps sont changés! Aussi vrai que je suis rieur, je préfère le plus simplement du monde la photo- graphie à l'art pictural et la lecture du Matin à celle de Racine. Pour vous, ceci demande une petite explication que je m'empresse de vous donner. Par exemple, il y a trois catégories de lecteurs de journaux : tout d'abord l'illettré, qui ne saurait prendre aucun goût à la lecture d'un chef- d'œuvre, puis l'homme supérieur, l'homme instruit, le monsieur distingué, sans imagination, qui lit à peine le journal parce qu'il a besoin de la fiction des autres, enfin l'homme ou la brute avec un tempérament qui sent son journal et qui se moque de la sen- sibilité des maîtres. -

(Thea 10.4/Wgst 59.5) Sex & Drama: Sexuality Theories/Theatrical

(THE 3313) Theatre History / Dramatic Literature 3 2015 Fall Instructor: Aaron C. Thomas Class: Mon/Wed/Fri, 1.30-2.20p Office: Performing Arts Center / T225 (second floor) Phone: (407) 823-3118 Office hours: Mon: 2.30-4.30p / Wed & Fri: 2.30-3.30p Email: [email protected] Graduate Teaching Assistant: Maria Katsadouros Office: Office: Performing Arts Center / T206 or T207 (second floor) Office hours: Wed 12.00-1.30p Email: [email protected] Course Description from the 2015-2016 Undergraduate Catalog Theatre history and drama from modern realism to present. Course Objectives The study of theatre history allows those who make and enjoy theatre to discover how theatrical practices of the past continue to influence trends in theatre, film, and storytelling in the present day. Learning about the history and the historical context of specific plays, artists, and performance practices allows makers and lovers of theatre to make connections between the ways in which theatre and society are always working to shape each other. How do performances try to support – or change – the cultures that produce them? What are some of the very different functions that performances can serve in a society? How do the reasons that audiences go to theatre change over time? These are some of the questions we will be asking as we journey through a hundred years of changes, challenges, risks, and struggles in the story of theatre and performance. This course is designed to introduce the student to significant periods of theatre history by: o Reading and discussing plays from important periods in theatre history. -

The Uncensored Writings of Elsa Von Freytag-Loringhoven

introduction “Say it with—— — Bolts! Oh thunder! Serpentine aircurrents—— — Hhhhhphssssssss! The very word penetrates! —LS e a von Freytag-Loringhoven, “a dozen cocktaiLS—pLeaSe” The immense cowardice of advertised literati & Elsa Kassandra, “the Baroness” von Freytag etc. sd/several true things in the old days/ driven nuts, Well, of course, there was a certain strain On the gal in them days in Manhattan the principle of non-acquiescence laid a burden. — ezra pound, canto 95 t he FirSt aMerican dada The Baroness is the first American Dada. — jane heap, 19201 “All America is nothing but impudent inflated rampantly guideless burgers—trades people—[…] as I say—: I cannot fight a whole continent.”2 On April 18, 1923, after having excoriated American artists, citizens, and law enforcement for more than a decade, the German-born Dadaist Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (1874–1927) was leaving New York. Waving farewell from the Port Authority pier was magazine editor Jane Heap, who had steadfastly championed the Baroness’s poetry in the pages of The Little Review. The water churning beneath the S.S. York that was carrying the Baroness back to Germany was nothing compared to the violent turbulences she had whirled up during her thirteen-year sojourn in America. No one had ever before seen a woman like the Baroness (figure I.1). In 1910, on arrival from Berlin, she was promptly arrested for promenading on Pittsburgh’s Fifth Avenue dressed in a man’s suit and smoking a cigarette, even garnering a headline in the New York Times: “She Wore Men’s Clothes,” it proclaimed aghast.3 Just as they were by her appearance, Americans were flabbergasted by the Baroness’s verse.