Overindebtedness in Microfinance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commencement2018

UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI COMMENCEMENT2018 MAY 11 • 8:30 a.m. R DR E WILDE DRIV C Gautier A CORAL GABLES CAMPUS RO M P Plaza O AMA S College of A N N SA O Cox Engineerin g A McArthur V E Scienc e N Engineerin g U Buildin g E Fieldhouse (Lineup site) Parking: Gate Buildin g Hous e E MILLER DRIV Special Needs Entrance Pavia Garage and Merrick Garage N RO McLamore AD ScSchoolhool of SO Traffic Light Special Needs Parking MEMORIAL DRIV E Plaza Nursing an d School of Law BRUN College of Health Studies Arts and Shuttle Route General Parking MILLER Sciences Shuttle Stop DRIV E Graduate Schoo l Construction Zone Fence Gusman E Foote U 11 Pedestrian Access Concer t N Frost Sc hool of Musi c School of E Hall Univer sity Green V A Shalal a Communication O U Statue Photo Booth Studen t N Wolfso n A S Center Feldenkrei s Buildin g I VE P RI Plaza Ride Share/Taxi Drop Off D O R A statue M A and Pick Up N Student Center Com plex A S Whitten School of Education UnivUn vveeersirs tyt Univ ersi ty and Human Development Villag e Center E ) Cobb Busines s Y DRIV Fountain ENUE Schoo l UNIVERSIT Lake Osceola W 57 AV (S Fate Bridge Cesarano AD RO Plaza D RE ST E A Herbe rt School of Architecture NFOR DRIV E Wellnes s Pere z D AN Center Archit ecture D R Center IV HURRIC E Murphy BRESCI Miller Design Studio BuildLab A Student AV Housing ENUE Village D R Watsco Center (Under Construction) A 12 Field house V Pavia E T L Newman Alumni U Garage EE Sebastian O Central R B Center Merric k A statue Energy Plant ST Garage D A A N VI A PA R Light Fiel d WALSH AVENUE EXTENSION G Gate E E V T LEVANTE AV E. -

5Pm Business & Engineering

UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI COMMENCEMENT2018 MAY 11 • 5 p.m. R DR E WILDE DRIV C Gautier A CORAL GABLES CAMPUS RO M P Plaza O AMA S College of A N N SA O Cox Engineerin g A McArthur V E Scienc e N Engineerin g U Buildin g E Fieldhouse (Lineup site) Parking: Gate Buildin g Hous e E MILLER DRIV Special Needs Entrance Pavia Garage and Merrick Garage N RO McLamore AD ScSchoolhool of SO Traffic Light Special Needs Parking MEMORIAL DRIV E Plaza Nursing an d School of Law BRUN College of Health Studies Arts and Shuttle Route General Parking MILLER Sciences Shuttle Stop DRIV E Graduate Schoo l Construction Zone Fence Gusman E Foote U 11 Pedestrian Access Concer t N Frost Sc hool of Musi c School of E Hall Univer sity Green V A Shalal a Communication O U Statue Photo Booth Studen t N Wolfso n A S Center Feldenkrei s Buildin g I VE P RI Plaza Ride Share/Taxi Drop Off D O R A statue M A and Pick Up N Student Center Com plex A S Whitten School of Education UnivUn vveeersirs tyt Univ ersi ty and Human Development Villag e Center E ) Cobb Busines s Y DRIV Fountain ENUE Schoo l UNIVERSIT Lake Osceola W 57 AV (S Fate Bridge Cesarano AD RO Plaza D RE ST E A Herbe rt School of Architecture NFOR DRIV E Wellnes s Pere z D AN Center Archit ecture D R Center IV HURRIC E Murphy BRESCI Miller Design Studio BuildLab A Student AV Housing ENUE Village D R Watsco Center (Under Construction) A 12 Field house V Pavia E T L Newman Alumni U Garage EE Sebastian O Central R B Center Merric k A statue Energy Plant ST Garage D A A N VI A PA R Light Fiel d WALSH AVENUE EXTENSION G Gate E E V T LEVANTE AV E. -

To the Pan Am Games

POST’S GUIDE to the PAN AM GAMES BADMINTONBadminton GUIDE TO THE GAMES B Y K AITLYN MC G RATH , NATIONAL POST Venue Atos Markham Pan Am/Parapan Am Centre. Venue acronym MAR Landmark status Medium This venue was built specifically for the Games and includes a tri- ple gymnasium and an Olympic- sized pool. Following the Games, it will become a multi-purpose community centre. In addi- tion, it’s located near downtown Unionville, which colleague Eric Koreen points out was a stand-in for the fictional town Stars Hol- low during the shooting of the pi- 2 NATIONAL POST GUIDE TO THE GAMES lot for the TV show Gilmore Girls. Other events at venue Table tennis (including Parapan Am) and water polo Transit options From the Union Station GO bus terminal board the 71C Lincoln- ville bus and exit at YMCA Boule- vard and Kennedy Road (stop called Markham) and walk a short distance to the venue. From Downsview Station, board the 71F Stouffville GO bus (toward Centennial). For exact directions, try: Triplinx.ca TTC trip planner 3 NATIONAL POST GUIDE TO THE GAMES Schedule July 11 Rounds of 64 and 32 matches July 12 Round of 16 July 13 Quarter-finals July 14 Semifinals July 15 Men’s and women’s doubles finals July 16 Men’s and women’s sin- gles finals, mixed doubles final See the full competition schedule at the Pan Am website How it works Thinking of the breezy, relaxed game played at the cottage won’t help here. World-class badmin- ton has players moving cross the court at a rapid pace with the shuttlecock reportedly able to travel faster than 300 km/h. -

Pagina 14Inter.Qxp

14 DEPORTES OCTUBRE 2011 > viernes 21 Brasil reinó ante unas Esta tarde, Cuba en los cubanas “maravilhosas” Ariel B. Coya, enviado especial lo que primó por sobre todo fueron las emociones. Y eso Juegos Panamericanos GUADALAJARA.—Venció que costó un set entrar en el Brasil a Cuba 3-2 (25-15, partido. Como explicaron lue- Cubavisión, Cubavisión Inter- 21-25, 25-21, 21-25 y 15-10) go los técnicos Juan Carlos nacional, Radio Rebelde y en un duelo pletórico, el clási- Gala y Eider George, el equi- Radio Habana Cuba transmiti- co por antonomasia del volei- po logró reponerse de un mal rán hoy, a las 6:30 p.m., la Mesa bol femenino. Y se tomó la comienzo en el que arranca- Redonda Informativa Cuba en revancha de aquella fantásti- ron demasiado imprecisas al los Juegos Panamericanos, ca final en el Maracanazinho punto de ceder los dos prime- con análisis sobre la actuación de la dele- de Río de Janeiro. Pero en ros tiempos técnicos (3-8 y gación nacional en la fiesta deportiva de nada demerita la derrota a las 6-16) frente a las auriverdes, FOTO: RICARDO LÓPEZ HEVIA, ENVIADO ESPECIAL América y otros temas de interés. antillanas, un conjunto reno- que aprovecharon sin piedad El Canal Educativo retransmitirá esta vado y joven, que a pesar de cada uno de sus fallos. nervios del quinto y decisivo. en los próximos años a los Mesa Redonda al final de su programa- los altibajos de la última tem- La segunda manga, sin Venció Brasil, que se mos- planos estelares, después de ción. -

Mixed Doubles

⇧ 2012 Back to Badzine Results Page ⇩ 2010 2011 Mixed Doubles Results Gold Silver Bronze Bronze World Championships Zhang Nan / Zhao Yunlei Chris Adcock / Imogen Bankier Xu Chen / Ma Jin Tontowi Ahmad / Liliyana Natsir Super Series 2010 Superseries Finals Zhang Nan / Zhao Yunlei Sudket Prapakamol / Saralee Thoungthongkam Songphon Anugritayawon / Kunchala Voravichitchaikul Ko Sung Hyun / Ha Jung Eun Malaysia Open He Hanbin / Ma Jin Tao Jiaming / Tian Qing Robert Blair / Gabrielle White Joachim Fischer-Nielsen / Christinna Pedersen Korea Open Zhang Nan / Zhao Yunlei Tao Jiaming / Tian Qing Xu Chen / Ma Jin Ko Sung Hyun / Ha Jung Eun All England Xu Chen / Ma Jin Sudket Prapakamol / Saralee Thoungthongkam Michael Fuchs / Birgit Michels Hendra Setiawan / Anastasia Russkikh India Open Tontowi Ahmad / Liliyana Natsir Fran Kurniawan / Pia Zebadiah Bernadeth Muhammad Rijal / Debby Susanto Chan Peng Soon / Goh Liu Ying Singapore Open Tontowi Ahmad / Liliyana Natsir Chen Hung Ling / Cheng Wen Hsing Zhang Nan / Zhao Yunlei Nathan Robertson / Jenny Wallwork Indonesia Open Zhang Nan / Zhao Yunlei Tontowi Ahmad / Liliyana Natsir Chen Hung Ling / Cheng Wen Hsing Thomas Laybourn / Kamilla Rytter Juhl China Masters Xu Chen / Ma Jin Yoo Yeon Seong / Chang Ye Na Joachim Fischer-Nielsen / Christinna Pedersen Diju Valiyaveetil / Jwala Gutta Japan Open Chen Hung Ling / Cheng Wen Hsing Joachim Fischer-Nielsen / Christinna Pedersen Zhang Nan / Zhao Yunlei Michael Fuchs / Birgit Michels Denmark Open Joachim Fischer-Nielsen / Christinna Pedersen Xu Chen / Ma Jin -

Study on EU Support to Justice and Security Sector Reform in Latin America and the Caribbean

Study on EU Support to Justice and Security Sector Reform in Latin America and the Caribbean Final Report / November 2013 This study was prepared by Robert Muggah, Victoria Walker, Ilona Szabo and Antoine Hanin. This study was financed by the European Union. The views expressed in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Commission, ISSAT1 or any of ISSAT’s other Governing Board members. 1 The International Security Sector Advisory Team (ISSAT) is an integral part of the Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF). It was created in 2008 to provide a standing capacity for its members to reinforce them in the support they provide to countries undergoing justice and security sector reform processes. More details can be found at http://issat.dcaf.ch Study on EU Support to Justice and Security Sector Reform in Latin America and the Caribbean Final Report – November 2013 Executive Summary Many Latin America and Caribbean countries face a dilemma in the twenty first century. On the one side are promising signs of democratic consolidation and steady economic growth. On the other side are some of the highest rates of criminal violence and socio-economic inequality in the world. The failure to prevent and reduce organised and street crime, injustice and impunity is in some societies deterring and disabling development, particularly among countries in the Caribbean, the northern triangle of Central America and some parts of South America. Governments across the region have adopted strategies ranging from heavy-fisted policing and incarceration to investments in primary and secondary prevention. -

Campeones Nacionales Primera Categoría Perú

CAMPEONES NACIONALES PRIMERA CATEGORÍA PERÚ MODALIDAD N° AÑO INDIVIDUAL FEMENINO INDIVIDUAL MASCULINO DOBLES FEMENINO DOBLES MASCULINO DOBLES MIXTO 1 1967 Rosario Copello Portocarrero Miguel Arguelles Rospigliosi Rosario Copello Portocarrero Margot Favaratto de Balbuena Mario Carrera Espinoza Miguel Carrera Espinoza Miguel Arguelles Rospigliosi Rosario Copello Portocarrero 2 1968 Josefina Delgado Larraín Miguel Arguelles Rospigliosi Josefina Delgado Larraín Sara Pinedo Hidalgo Miguel Arguelles Rospigliosi Percy Levi Arias Mario Carrera Espinoza Josefina Delgado Larraín 3 1969 Josefina Delgado Larraín Miguel Arguelles Rospigliosi Josefina Delgado Larraín Sara Pinedo Hidalgo Mario Carrera Espinoza Miguel Carrera Espinoza Mario Carrera Espinoza Josefina Delgado Larraín 4 1970 Josefina Delgado Larraín Miguel Arguelles Rospigliosi Josefina Delgado Larraín Sara Pinedo Hidalgo Alfredo Salazar Perez Guillermo Zavala Dancuart Alfredo Salazar Perez Josefina Delgado Larraín 5 1971 No hubo torneo No hubo torneo No hubo torneo No hubo torneo No hubo torneo No hubo torneo No hubo torneo No hubo torneo 6 1972 Ofelia Noriega Zegarra Guillermo Zavala Dancuart Ofelia Noriega Zegarra Patricia Woyke Cuglievan Alfredo Salazar Perez Guillermo Zavala Dancuart Alfredo Salazar Perez Josefina Delgado Larraín 7 1973 Ofelia Noriega Zegarra Guillermo Zavala Dancuart Josefina Delgado Larraín Pilar Ibarra Gunther Jorge Gallegos Rossini Ricardo Newton Thursfield Guillermo Zavala Dancuart Josefina Delgado Larraín 8 1974 Ofelia Noriega Zegarra Guillermo Zavala Dancuart -

Women's Doubles Results Gold Silver Bronze Bronze Beijing Olympic Games Du Jing / Yu Yang Lee Hyo Jung / Lee Kyung Won Wei Yili / Zhang Yawen

⇧ 2009 Back to Badzine Results Page ⇩ 2007 2008 Women's Doubles Results Gold Silver Bronze Bronze Beijing Olympic Games Du Jing / Yu Yang Lee Hyo Jung / Lee Kyung Won Wei Yili / Zhang Yawen Super Series Malaysia Open Yang Wei / Zhang Jiewen Gao Ling / Zhao Tingting Du Jing / Yu Yang Lee Hyo Jung / Lee Kyung Won Korea Open Du Jing / Yu Yang Gao Ling / Zhao Tingting Wei Yili / Zhang Yawen Lee Hyo Jung / Lee Kyung Won All England Lee Hyo Jung / Lee Kyung Won Du Jing / Yu Yang Wei Yili / Zhang Yawen Yang Wei / Zhang Jiewen Swiss Open Yang Wei / Zhang Jiewen Wei Yili / Zhang Yawen Lee Hyo Jung / Lee Kyung Won Du Jing / Yu Yang Singapore Open Du Jing / Yu Yang Cheng Wen Hsing / Chien Yu Chin Ha Jung Eun / Kim Min Jung Vita Marissa / Liliyana Natsir Indonesia Open Vita Marissa / Liliyana Natsir Miyuki Maeda / Satoko Suetsuna Wei Yili / Zhang Yawen Shendy Puspa Irawati / Meiliana Jauhari Japan Open Cheng Shu / Zhao Yunlei Chin Eei Heui / Wong Pei Tty Miyuki Maeda / Satoko Suetsuna Vita Marissa / Liliyana Natsir China Masters Cheng Shu / Zhao Yunlei Zhang Dan / Zhang Zhibo Duang Anong Aroonkesorn / Kunchala Voravichitchaikul Nicole Grether / Charmaine Reid Denmark Open Chin Eei Heui / Wong Pei Tty Rani Mundiasti / Jo Novita Nitya Krishinda Maheswari / Gresya Polii Judith Meulendijks / Yao Jie French Open Du Jing / Yu Yang Chin Eei Heui / Wong Pei Tty Cheng Shu / Zhao Yunlei Zhang Yawen / Zhao Tingting China Open Zhang Yawen / Zhao Tingting Chin Eei Heui / Wong Pei Tty Du Jing / Yu Yang Ha Jung Eun / Kim Min Jung Hong Kong Open Zhang Yawen / Zhao -

2007 Report Contents

200 5-2008 Quadrennial Plan 2007 Report Contents Introduction Message by the Chairman of the Olympic Solidarity Commission 2 Analysis of the year 2007 4 Olympic Solidarity History 5 Olympic Solidarity Commission 6 Olympic Solidarity Offices and Human Resources 7 World and Continental Programmes 9 Programmes and Budgets 10 A Worldwide Partnership 11 World Programmes .................................................................................................................... 14 Athletes 16 Olympic Scholarships for Athletes “Beijing 200 8” 17 Team Support Grants 19 Continental and Regional Games – NOC Preparation 20 2012 – Training Grants for Young Athletes 21 Talent Identification 22 Coaches 24 Technical Courses for Coaches 25 Olympic Scholarships for Coaches 27 Development of National Sports Structure 29 NOC Management 32 NOC Administration Development 33 National Training Courses for Sports Administrators 34 International Executive Training Courses in Sports Management 35 NOC Exchange and Regional Forums 37 Promotion of Olympic Values 38 Sports Medicine 39 Sport and the Environment 40 Women and Sport 41 Sport for All 42 International Olympic Academy 43 Culture and Education 44 NOC Legacy 45 Continental Programmes ................................................................................... ..................... 48 Reports by the Continental Associations Association of National Olympic Committees of Africa (ANOC A) 50 Pan American Sports Organisation (PAS O) 58 Olympic Council of Asia (OC A) 66 The European Olympic Committees -

Women's Singles Results Gold Silver Bronze Bronze World Championships Zhu Lin Wang Chen Zhang Ning Lu Lan

⇧ 2008 Back to Badzine Results Page 2007 Women's Singles Results Gold Silver Bronze Bronze World Championships Zhu Lin Wang Chen Zhang Ning Lu Lan Super Series Malaysia Open Zhu Lin Wong Mew Choo Yao Jie Eriko Hirose Korea Open Xie Xingfang Zhu Lin Petya Nedelcheva Lu Lan All England Xie Xingfang Pi Hongyan Zhu Lin Zhang Ning Swiss Open Zhang Ning Lu Lan Xu Huaiwen Jiang Yanjiao Singapore Open Zhang Ning Xie Xingfang Xu Huaiwen Eriko Hirose Indonesia Open Wang Chen Zhu Lin Pi Hongyan Petya Nedelcheva China Masters Xie Xingfang Zhang Ning Pi Hongyan Yip Pui Yin Japan Open Tine Baun Xie Xingfang Lu Lan Jun Jae Youn Denmark Open Lu Lan Zhang Ning Wang Chen Zhu Lin French Open Xie Xingfang Pi Hongyan Wong Mew Choo Zhang Ning China Open Wong Mew Choo Xie Xingfang Lu Lan Zhang Ning Hong Kong Open Xie Xingfang Zhu Lin Lu Lan Jun Jae Youn Grand Prix Gold Thai Open Zhu Lin Zhou Mi Pi Hongyan Xing Aiying Philippine Open Zhou Mi Zhu Jingjing Adrianti Firdasari Juliane Schenk Chinese Taipei Open Wang Chen Pi Hongyan Yao Jie Yip Pui Yin Macau Open Xie Xingfang Jun Jae Youn Adrianti Firdasari Lu Lan Russian Open Wang Yihan Xu Huaiwen Pai Hsiao Ma Fransiska Ratnasari ⇧ 2008 Back to Badzine Results Page 2007 Women's Singles Results Gold Silver Bronze Bronze Grand Prix German Open Xie Xingfang Xu Huaiwen Petya Nedelcheva Pi Hongyan New Zealand Open Zhou Mi Chie Umezu Pi Hongyan Yip Pui Yin U.S. Open Jun Jae Youn Lee Yun Hwa Pai Hsiao Ma Elizabeth Cann Bitburger Open Wang Yihan Juliane Schenk Zhu Jingjing Jiang Yanjiao Dutch Open Li Wenyan Judith Meulendijks -

Download Schedule(PDF)

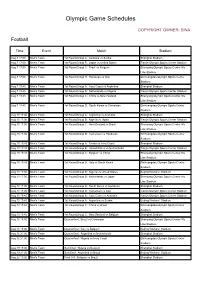

Olympic Game Schedules COPYRIGHT OWNER: SINA Football Time Event Match Stadium Aug.7 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup A : Australia vs Serbia Shanghai Stadium Aug.7 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup B : Japan vs United States Tianjin Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.7 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup C : Brazil vs Belgium Shenyang Olympic Sports Center Wu Lihe Stadium Aug.7 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup D : Honduras vs Italy Qinhuangdao Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.7 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup A : Ivory Coast vs Argentina Shanghai Stadium Aug.7 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup B : Netherlands vs Nigeria Tianjin Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.7 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup C : China vs New Zealand Shenyang Olympic Sports Center Wu Lihe Stadium Aug.7 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup D : South Korea vs Cameroon Qinhuangdao Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.10 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup A : Argentina vs Australia Shanghai Stadium Aug.10 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup B : Nigeria vs Japan Tianjin Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.10 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup C : New Zealand vs Brazil Shenyang Olympic Sports Center Wu Lihe Stadium Aug.10 17:00 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup D : Cameroon vs Honduras Qinhuangdao Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.10 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup A : Serbia vs Ivory Coast Shanghai Stadium Aug.10 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup B : United States vs Netherlands Tianjin Olympic Sports Center Stadium Aug.10 19:45 Men's Team 1st RoundGroup C : Belgium vs China Shenyang Olympic Sports Center Wu -

CICAD (VIRTUAL SESSION) OEA/Ser.L/XIV.1.67 August 13, 2020 CICAD/Doc.2532/20 Washington D.C, United States July 17, 2020 Original: English

INTER-AMERICAN DRUG ABUSE CONTROL COMMISSION C I C A D Secretariat for Multidimensional Security SIXTY-SEVENTH REGULAR SESSION OF CICAD (VIRTUAL SESSION) OEA/Ser.L/XIV.1.67 August 13, 2020 CICAD/doc.2532/20 Washington D.C, United States July 17, 2020 Original: English Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission (CICAD) List of Participants CICAD 67 Inter-American Drug Abuse Control Commission (CICAD) List of Participants CICAD 67 ESTADOS MIEMBROS DE LA CICAD / CICAD MEMBER STATES Argentina Gabriela Torres – Secretaria de Políticas Integrales sobre Drogas de la Nación Argentina (Secretaria de SEDRONAR) Valentina Novick – Subsecretaria de Investigación Criminal y Cooperación Judicial Gabriela Dorrego Maria Eugenia Mihura Elisa Sproviero Pablo Vera Nicolás Abraham Delfina Faraoni Manochi Pablo Serdan Juan Martin Chippano Tiago Martin Mauricio Nine Fernando Ricci Maria Lorena Capra Bahamas Terrance Fountain – Director, National Anti-Drug Secretariat Barbados Deborah Payne – Permanent Secretary, Ministry of Home Affairs Betty Hunte – Manager, National Council on Substance Abuse Troy Wickham – Deputy Manager, National Council on Substance Abuse Maryam Hinds – Director, Barbados Drug Service Ronald Chase – Psychiatrist, Psychiatric Hospital Percival Campbell Rosamund Lovell Lindsay Bynoe Makeada Bourne Paulavette Atkinson Jonathan Yearwood Bolivia Arturo Murillo – Ministro de Gobierno Jaime Zamora – Viceministro de Defensa Social Emb. Jaime Aparicio Otero – Representante Permanente Erick Foronda Ignacio Jauregui Maria del Carmen Castellon Juan