Red's Arresting Women

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2 a Quotation of Normality – the Family Myth 3 'C'mon Mum, Monday

Notes 2 A Quotation of Normality – The Family Myth 1 . A less obvious antecedent that The Simpsons benefitted directly and indirectly from was Hanna-Barbera’s Wait ‘til Your Father Gets Home (NBC 1972–1974). This was an attempt to exploit the ratings successes of Norman Lear’s stable of grittier 1970s’ US sitcoms, but as a stepping stone it is entirely noteworthy through its prioritisation of the suburban narrative over the fantastical (i.e., shows like The Flintstones , The Jetsons et al.). 2 . Nelvana was renowned for producing well-regarded production-line chil- dren’s animation throughout the 1980s. It was extended from the 1960s studio Laff-Arts, and formed in 1971 by Michael Hirsh, Patrick Loubert and Clive Smith. Its success was built on a portfolio of highly commercial TV animated work that did not conform to a ‘house-style’ and allowed for more creative practice in television and feature projects (Mazurkewich, 1999, pp. 104–115). 3 . The NBC US version recast Feeble with the voice of The Simpsons regular Hank Azaria, and the emphasis shifted to an American living in England. The show was pulled off the schedules after only three episodes for failing to connect with audiences (Bermam, 1999, para 3). 4 . Aardman’s Lab Animals (2002), planned originally for ITV, sought to make an ironic juxtaposition between the mistreatment of animals as material for scientific experiment and the direct commentary from the animals them- selves, which defines the show. It was quickly assessed as unsuitable for the family slot that it was intended for (Lane, 2003 p. -

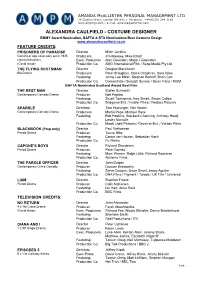

Alexandra Caulfield - Costume Designer

AMANDA McALLISTER PERSONAL MANAGEMENT LTD 74 Claxton Grove, London W6 8HE • Telephone: +44(0)207 244 1159 www.ampmgt.com • e-mail: [email protected] ALEXANDRA CAULFIELD - COSTUME DESIGNER EMMY Award Nomination, BAFTA & RTS Nominations Best Costume Design www.alexandracaulfield.co.uk FEATURE CREDITS: PRISONERS OF PARADISE Director Mitch Jenkins Coming of age Love story set in 1925 Producers Jim Mooney, Mike Elliott colonial Mauritius Exec. Producers Alan Govinden, Maria J Govinden (Covid shoot) Production Co. AMG International Film / Sega Media Pty Ltd THE FLYING SCOTSMAN Director Douglas Mackinnon Bio Drama Producers Peter Broughan, Claire Chapman, Sara Giles Featuring Jonny Lee Miller, Stephen Berkoff, Brian Cox Production Co. ContentFilm / Scottish Screen / Scion Films / MGM BAFTA Nominated Scotland Award Best Film THE BEST MAN Director Stefan Schwartz Contemporary Comedy Drama Producer Neil Peplow Featuring Stuart Townsend, Amy Smart, Simon Callow Production Co. Endgame Ent. / Insider Films / Redbus Pictures SPARKLE Directors Tom Hunsinger, Neil Hunter Contemporary Comedy Drama Producers Martin Pope, Michael Rose Featuring Bob Hoskins, Stockard Channing, Anthony Head, Lesley Manville Production Co. Magic Light Pictures / Revolver Ent. / Vertigo Films BLACKBOOK (Prep only) Director Paul Verhoeven Period Drama Producer Teune Hilte Featuring Carice van Houten, Sebastian Koch Production Co. Fu Works CAPONE’S BOYS Director Richard Standeven Period Drama Producer Peter Barnes Featuring Marc Warren, Ralph Little, Richard Rowntree Production Co. Alchemy Films THE PAROLE OFFICER Director John Duigan Contemporary Crime Comedy Producer Duncan Kenworthy Featuring Steve Coogan, Omar Sharif, Jenny Agutter Production Co. DNA Films / Figment / Toledo / UK Film / Universal LIAM Director Stephen Frears Period Drama Producer Colin McKeown Featuring Ian Hart, Anne Reid Production Co. -

Ordinary Lies

Ordinary Lies TX: Tuesday 17 March 2015 (TBC) BBC One 6 x 60min For further information: Katy Ardagh: 020 7292 7358 / [email protected] Ruth Bray: 020 7292 8348 / [email protected] Amy Shacklady: 020 7292 7373 / [email protected] 1 Contents Press Release 3 Cast List 4 Cast Interviews Danny Brocklehurst Series creator and writer 5 Jason Manford Plays Marty McLean 7 Jo Joyner Plays Beth Corbin 9 Sally Lindsay Plays Kathy Kavanagh 11 Episode 1 Synopsis 13 2 Ordinary Lies How well do you really know the people who work around you? From RED Production Company, creators of hit series Happy Valley and Last Tango In Halifax, comes highly-anticipated new primetime drama, Ordinary Lies, penned by BAFTA and International Emmy award-winning writer, Danny Brocklehurst (Accused, Shameless). We all tell little white lies everyday be it for self-protection, success or for love. But what happens when a spur-of-the-moment mistruth snowballs and begins to take over? Is it possible get away with it, or will the lie inevitably come undone to devastating effect? Set in a car showroom, Ordinary Lies is a compelling drama about how a simple lie can spiral out of control. With drama, tragedy, warmth and humour, each episode focuses on one of the colleagues and friends of JS Motors. From party-loving receptionists, Tracy (Michelle Keegan) and Viv (Cherelle Skeet) and ambitious company boss, Mike (Max Beesley) to enigmatic salesman, Pete (Mackenzie Crook) and mothering PA, Kathy (Sally Lindsay), each new and individual story questions just how well we know the people we work with. -

John Collins Production Designer

John Collins Production Designer Credits include: BRASSIC Director: Rob Quinn, George Kane Comedy Drama Series Producer: Mags Conway Featuring: Joseph Gilgun, Michelle Keegan, Damien Molony Production Co: Calamity Films / Sky1 FEEL GOOD Director: Ally Pankiw Drama Series Producer: Kelly McGolpin Featuring: Mae Martin, Charlotte Richie, Sophie Thompson Production Co: Objective Fiction / Netflix THE BAY Directors: Robert Quinn, Lee Haven-Jones Crime Thriller Series Producers: Phil Leach, Margaret Conway, Alex Lamb Featuring: Morven Christie, Matthew McNulty, Louis Greatrex Production Co: Tall Story Pictures / ITV GIRLFRIENDS Directors: Kay Mellor, Dominic Leclerc Drama Series Producer: Josh Dynevor Featuring: Miranda Richardson, Phyllis Logan, Zoe Wanamaker Production Co: Rollem Productions / ITV LOVE, LIES AND RECORDS Directors: Dominic Leclerc, Cilla Ware Drama Producer: Yvonne Francas Featuring: Ashley Jensen, Katarina Cas, Kenny Doughty Production Co: Rollem Productions / BBC One LAST TANGO IN HALIFAX Director: Juliet May Drama Series Producer: Karen Lewis Featuring: Sarah Lancashire, Nicola Walker, Derek Jacobi Production Co: Red Production Company / Sky Living PARANOID Directors: Kenny Glenaan, John Duffy Detective Drama Series Producer: Tom Sherry Featuring: Indira Varma, Robert Glennister, Dino Fetscher Production Co: Red Production Company / ITV SILENT WITNESS Directors: Stuart Svassand Mystery Crime Drama Series Producer: Ceri Meryrick Featuring: Emilia Fox, Richard Lintern, David Caves Production Co: BBC One Creative Media Management -

Michelle Heaney Editor

AMANDA MCALLISTER PERSONAL MANAGEMENT LTD 74 Claxton Grove, London W6 8HE • Telephone: +44 (0) 207 244 1159 www.ampmgt.com • e-mail: [email protected] MICHELLE HEANEY EDITOR CREDITS INCLUDE: THE REUNION Director Bill Eagles Thriller Drama Series Producer Sydney Gallonde Episodes 2, 4 & 6 (Remote editing) Production Co. MGM International TV Prods / Make It Happen Studio / France Télévisions STAY CLOSE Director Lindy Heymann 8 x 1hr Contemporary Drama Producer Juliet Charlesworth Episodes 5 & 6 Exec. Producers Nicola Shindler, Harlan Coben, Richard Fee, Danny Brocklehurst Production Co. Red Production Company / Netflix TRACES Director Rebecca Gatward 2 x 1hr Crime Mystery Thriller Drama Producer Juliet Charlesworth (Additional Editor) Exec. Producers Nicola Shindler, Michaela Fereday, Liam Keelan Philippa Collie Cousins, Val McDermid Production Co. Red Production Company / ALIBI BAFTA Nomination Best Drama Series THE WORST WITCH Director Dermot Boyd 4 x ½hr Children’s Drama Series Producer Kim Crowther Exec. Producer Sue Knott Production Co. CBBC / Netflix / ZDF Enterprises THE STRANGER Director Daniel O’Hara 3 x 1hr Mystery Crime Drama Producer Madonna Baptiste (1st Assistant Editor) Exec. Producers Nicola Shindler, Harlan Coben, Danny Brocklehurst, Richard Fee Editor Steve Singleton Production Co. Red Production Company / Netflix BRASSIC Directors Daniel O'Hara, Jon Wright 6 x 1hr Comedy Series Producer Juliet Charlesworth (1st Assistant Editor/ Assembly Editor) Exec. Producers David Livingston, Joe Gilgun, Danny Brocklehurst, Jon Montague Editors Annie Kocur, Rachel Hoult Production Co. SKY / Calamity Films THE ROOK Director Kari Skogland 3 x 1hr Fantasy Thriller Drama Series Producer Steve Clark-Hall (1st Assistant Editor) Exec. Producer Stephen Garrett Editor Oral Ottey Production Co. -

Sky 1 Announces New Comedy Drama Living the Dream 23Rd May | Big Talk, Productions, TV

7/18/2017 Big Talk | Sky 1 announces new comedy drama Livingn The Dreamews Sky 1 announces new comedy drama Living The Dream 23rd May | Big Talk, Productions, TV Philip Glenister and Lesley Sharp star alongside Kim Fields, Kevin Nash, Leslie Jordan, Paula Wilcox and Jimmy Akingbola. Living the Dream, a brand new comedy drama from the makers of Cold Feet, is coming to Sky 1 later this year. Starring Philip Glenister (Outcast, Mad Dogs) and Lesley Sharp (Scott & Bailey, Paranoid), the series has been created and written by Mick Ford (Single Father, The Five), produced by Big Talk Productions (Cold Feet, Mum, Rev.) and will be directed by Saul Metzstein (Doctor Who, You, Me and the Apocalypse) and Philippa Langdale (Dickensian, Skins). The six-part series follows a British family, the Pembertons – husband Mal (Glenister), wife Jen (Sharp) and their two teenage kids, Tina (Rosie Day) and https://www.bigtalkproductions.com/sky-1-announces-new-comedy-drama-living-the-dream/ 1/3 7/18/2017 Big Talk | Sky 1 announces new comedy drama Living The Dream Freddie (Brenock O’Connor) – who decide it’s time to leave rainy England and move to the sunshine state of Florida. Mal’s bought an RV park with plans for a booming family-run business, but it soon turns out that they are not going to be living the dream they hoped. Before they’ve even settled in, Mal discovers that the park is home to a group of eccentric residents who are not exactly thrilled to meet their new owners. Jen has to learn how to survive American suburbia and the kids have to navigate a US high school. -

ABC Kids/ABC TV Plus Program Guide: Week 33 Index

1 | P a g e ABC Kids/ABC TV Plus Program Guide: Week 33 Index Index Program Guide .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Sunday, 8 August 2021 .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Monday, 9 August 2021 ........................................................................................................................................ 8 Tuesday, 10 August 2021 .................................................................................................................................... 13 Wednesday, 11 August 2021 .............................................................................................................................. 19 Thursday, 12 August 2021 ................................................................................................................................... 25 Friday, 13 August 2021 ....................................................................................................................................... 31 Saturday, 14 August 2021 ................................................................................................................................... 37 2 | P a g e ABC Kids/ABC TV Plus Program Guide: Week 33 Sunday 8 August 2021 Program Guide Sunday, 8 August 2021 5:05am Miffy's Adventures Big and Small (Repeat,G) 5:15am The Furchester Hotel (Repeat,G) -

Special Events: Film and Television Programme

Left to right: Show Me Love, Gas Food Lodging, My Own Private Idaho, Do the Right Thing Wednesday 12 June 2019, London. Throughout July and August BFI Southbank will host a two month exploration of explosive, transformative and challenging cinema and TV made from 1989-1999 – the 1990s broke all the rules and kick-started the careers of some of the most celebrated filmmakers working today, from Quentin Tarantino and Richard Linklater to Gurinder Chadha and Takeshi Kitano. NINETIES: YOUNG SOUL REBELS will explore work that dared to be different, bold and exciting filmmaking that had a profound effect on pop culture and everyday life. The influence of these titles can still be felt today – from the explosive energy of Do the Right Thing (Spike Lee, 1989) through to the transformative style of The Blair Witch Project (1999) and The Matrix (The Wachowskis, 1999). Special events during the season will include a 90s film quiz, an event celebrating classic 90s children’s TV, black cinema throughout the decade and the world cinema that made waves. Special guests attending for Q&As and introductions will include Isaac Julien (Young Soul Rebels), Russell T Davies (Queer as Folk) and Amy Jenkins (This Life). SPECIAL EVENTS: - The season will kick off with a special screening Do the Right Thing (Spike Lee, 1989) on Friday 5 July, presented in partnership with We Are Parable; Spike Lee’s astute, funny and moving film stars out with a spat in an Italian restaurant in Brooklyn, before things escalate to a tragic event taking place in the neighbourhood. -

A Production Spring 2011 | Follies Chicago Shakespeare Theater About CST

A production Spring 2011 | Follies CHICAGO SHAKESPEARE Theater About CST Chicago Shakespeare Theater (CST) is a leading international theater company, known for vibrant productions that reflect Shakespeare’s genius for intricate storytelling, musicality of language and depth of feeling for the human condition. Recipient of the 2008 Regional Theatre Tony Award, Chicago Shakespeare’s work has been recognized internationally with three of London’s prestigious Laurence Olivier Awards, and by the Chicago theater community with 62 Joseph Jefferson Awards for Artistic Excellence. Under the leadership of Artistic Director Barbara Gaines and Executive Director Criss Henderson, CST is dedicated to producing extraordinary productions of classics, new works and family fare; unlocking Shakespeare’s work for educators and students; and serving as Chicago’s cultural ambassador through its World’s Stage Series. At its permanent, state-of-the-art facility on Navy Pier, CST houses two intimate theater spaces: the 500-seat Jentes Family Courtyard Theater and the 200-seat Carl and Marilynn Thoma Theater Upstairs at Chicago Shakespeare. Through a year-round season encompassing more than 600 performances, CST leads the community as the largest employer of Chicago actors and attracts nearly 200,000 audience members annually—including 40,000 students and teachers through its comprehensive education programs. n BOARD OF DIRECTORS Raymond F. McCaskey William L. Hood, Jr. Glenn R. Richter Chair Stewart S. Hudnut Mark E. Rose Mark S. Ouweleen William R. Jentes Sheli Rosenberg Treasurer Gregory P. Josefowicz John W. Rowe James J. Junewicz Robert Ryan Frank D. Ballantine Jack L. Karp Carole B. Segal Brit J. Bartter John P. -

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 14 – 20 March 2015

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 14 – 20 March 2015 Page 1 of 9 SATURDAY 14 MARCH 2015 Marie Antoinette, Alexandrine Zola, Adolf Hitler and Charles Although it's the Poldarks that brought Winston Graham the de Gaulle who lighten and darken the city's streets most fame, he also wrote more than 30 other novels, six of SAT 00:00 The Seventh Test by Vikas Swarup (b044jh6l) in five episodes for BOOK OF THE WEEK. The series which have been filmed including the thriller, Marnie directed The Noose narrator is Stephen Boxer. by Alfred Hitchcock in 1964. Sapna Sinha works as a sales assistant in a TV showroom in In this final episode, we witness gunshots at Notre Dame, which This selection celebrates the range of his work and offers a New Delhi. Being the only bread-winner in the family she heralds decades of danger for glimpse into the enduring appeal of his most famous characters, works long hours to provide for her widowed mother and a new French leader... Reader Stephen Boxer. Ross and Demelza who are set to return to BBC screens in a younger sister. But then a man walks into her life with an SAT 01:00 The Museum of Curiosity (b0167zkv) new adaptation. extraordinary proposition: pass seven "life" tests of his choosing Series 4 Made for BBC Radio 4 Extra by The Waters Partnership. and she will have wealth and power. At first the tests seem easy, Haynes, McCandless, Crystal SAT 04:15 Neil Brand - Joanna (b00r9xm6) but things are not quite as they seem. -

Announcing a VIEW from the BRIDGE

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE “One of the most powerful productions of a Miller play I have ever seen. By the end you feel both emotionally drained and unexpectedly elated — the classic hallmark of a great production.” - The Daily Telegraph “To say visionary director Ivo van Hove’s production is the best show in the West End is like saying Stonehenge is the current best rock arrangement in Wiltshire; it almost feels silly to compare this pure, primal, colossal thing with anything else on the West End. A guileless granite pillar of muscle and instinct, Mark Strong’s stupendous Eddie is a force of nature.” - Time Out “Intense and adventurous. One of the great theatrical productions of the decade.” -The London Times DIRECT FROM TWO SOLD-OUT ENGAGEMENTS IN LONDON YOUNG VIC’S OLIVIER AWARD-WINNING PRODUCTION OF ARTHUR MILLER’S “A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE” Directed by IVO VAN HOVE STARRING MARK STRONG, NICOLA WALKER, PHOEBE FOX, EMUN ELLIOTT, MICHAEL GOULD IS COMING TO BROADWAY THIS FALL PREVIEWS BEGIN WEDNESDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 21 OPENING NIGHT IS THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 12 AT THE LYCEUM THEATRE Direct from two completely sold-out engagements in London, producers Scott Rudin and Lincoln Center Theater will bring the Young Vic’s critically-acclaimed production of Arthur Miller’s A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE to Broadway this fall. The production, which swept the 2015 Olivier Awards — winning for Best Revival, Best Director, and Best Actor (Mark Strong) —will begin previews Wednesday evening, October 21 and open on Thursday, November 12 at the Lyceum Theatre, 149 West 45 Street. -

No Offence the Aims of This Factsheet Are to Demonstrate the Way the Theoretical Abbot Has a Long Relationship with Channel 4

Media Studies www.curriculum-press.co.uk Number 184 Applying the Theoretical Framework: No Offence The aims of this Factsheet are to demonstrate the way the theoretical Abbot has a long relationship with Channel 4. Channel 4 are a framework can be applied to the television CSP, No Offence including commercial broadcaster but they also receive some government the industrial context of No Offence and the way the programme uses funding. To receive the public money, Channel 4 has to ensure media language: that (amongst other things) its programming is innovative, offers • To position the programme as part of a genre. alternative points of view and reflects the cultural diversity of the country. • To create narrative. Channel 4 buys programming from production companies and, when • To construct representations. doing so, will consider how the programme will help support its • To appeal to audiences. remit. Programmes which fit into Channel 4’s brand identity are No Offence is one of the options available for the study of television more likely to be bought by the broadcaster. products for AQA’s AS and A Level qualifications. Having a distinctive production background and being a ‘Channel • For AS Media Studies, it is a targeted CSP and should be 4 programme’ adds to the branding of No Offence itself and helps studied considering Audience and Industry ideas. audiences know what to expect from the programme. With no other • For A Level Media Studies, it is an in-depth CSP and information about the show, audiences would assume it would have should be studied considering all areas of the framework an irreverent approach to storytelling and may provide representations – Media Language, Representation, Audience and and storylines that are unconventional.