Independence Lake Spillway Fish Barrier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West Walker Watershed Management Plan

West Walker River Watershed Plan Management Plan March-2007 West Walker River Watershed Management Plan 1 Context Watershed approach California’s watershed programs and Mono County’s involvement Overview of issues and problems Problems linked to potential causes Water quantity Water quality Vegetation change Potential watershed problems and risks Knowledge and information gaps General principles of this watershed plan Main issues and potential solutions List of issues and solutions Potential problems of the future Recommended policies and programs List of goals, objectives, possible actions, and details Applicable best management practices Opportunities for governmental agencies and citizens groups Public education and outreach Monitoring Summary and conclusions Literature cited CONTEXT Watershed Approach The natural unit for considering most water-related issues and problems is the watershed. A watershed can be simply defined as the land contributing water to a stream or river above some particular point. Natural processes and human activities in a watershed influence the quantity and quality of water that flows to the point of interest. Despite the obvious connections between watersheds and the streams that flow from them, water problems are typically looked at and dealt with in an isolated manner. Many water West Walker River Watershed Management Plan 2 problems have been treated within the narrow confines of political jurisdictions, property boundaries, technical specialties, or small geographic areas. Many water pollution problems, flood hazards, or water supply issues have only been examined within a short portion of the stream or within the stream channel itself. What happens upstream or upslope has been commonly ignored. The so-called watershed approach merely attempts to look at the broad picture of an entire watershed and how processes and activities within that watershed affect the water that arrives at the defining point. -

Cottonwood Lakes / New Army Pass Trail

Inyo National Forest Cottonwood Lakes / New Army Pass Trail Named for the cottonwood trees which were located at the original trailhead in the Owens Valley, the Cottonwood Lakes are home to California's state fish, the Golden Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss aguabonita). The lakes are located in an alpine basin at the southern end of the John Muir Wilder- ness. They are surrounded by high peaks of the Sierra Nevada, including Cirque Peak and Mt. Lang- ley. The New Army Pass Trail provides access to Sequoia National Park and the Pacific Crest Trail. Trailhead Facilities: Water: Yes Bear Resistant Food Storage Lockers: Yes Campgrounds: Cottonwood Lakes Trailhead Campground is located at the trailhead. Visitors with stock may use Horseshoe Meadow Equestrian Camp, located nearby. On The Trail: Food Storage: Food, trash and scented items must be stored in bear-resistant containers. Camping: Use existing campsites. Camping is prohibited within 25 feet of the trail, and within 100 feet of water. Human Waste: Bury human waste 6”-8” deep in soil, at least 100 feet from campsites, trails, and water. Access: Campfires: Campfires are prohibited above 10,400 ft. The trailhead is located approximately 24 miles southwest of Lone Pine, CA. From Highway Pets: Pets must be under control at all times. 395 in Lone Pine, turn west onto Whitney Portal Additional Regulations: Information about Kings Road. Drive 3.5 miles and turn south (left) onto Canyon National Park regulations is available at Horseshoe Meadow Road. Travel approximately www.nps.gov/seki, www.fs.usda.gov/goto/inyo/ 20 miles, turn right and follow signs to the cottonwoodlakestrail or at Inyo National Forest Cottonwood LAKES Trailhead. -

Numaga Indian Days Pow Wow Enters Its 28Th Year

VOLUME IX ISSUE 12 August 22, 2014 Numaga Indian Days Pow Wow Enters Its 28th Year Hundreds expected for nationally known event held in Hungry Valley Each Labor Day weekend, the stunning handcrafted silver- from Frog Lake, Alberta Reno-Sparks Indian Colony work, beadwork, baskets and Canada. hosts its nationally acclaimed other American Indian art. Carlos Calica of Warm Numaga Pow Wow. This year, the 28th annual Springs, Oregon will serve as This family event features event, will be August 29-31 in the master of ceremonies, while some of the best Native Hungry Valley. Hungry Valley is the arena director will be Tom American dancers, singers and 19 miles north of downtown Phillips, Jr., from Wadsworth, drummers in the country. Reno and west of Spanish Nev. Besides the memorable pow Springs, nestled in scenic Eagle The Grand Entry will start wow entertainment, over 25 Canyon. at 7 p.m., on Friday, noon and vendors will be selling The host drum for this year‘s again at 7 p.m., on Saturday, traditional native foods and pow wow will be Young Spirit then at noon on Sunday. The pow wow is named after Chief Numaga, the famous Paiute Chief, known for peace. Chief Numaga was a great 19th century leader who had the courage and the vision to counsel against war. Facing severe threats to his people by invading white forces, Numaga repeatedly chose peace. His successful peace negotia- tions, helped set a precedent for future disputes. However, despite consistent calls for peace, an 1860 incident so severe forced Numaga to call for force. -

Walkerriverdecree.Pdf

Filed__________ 191W J IN EQUITY --___________, Clerk NO. C-125 By____________, Deputy IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, IN AND FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEVADA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ~ t! Plainttff, ) ·vs- ( WALKER RIVER IRRIGATION l DISTRICT, a corporation, () et al, ) Defendants. ( ORDER FOR ENT::rl OF AttEHDED FINAL DECREE ~6----------'CONFD'RM"rT'OWRITOFMANDATE E'Tc.--:- The court entered its final decree in the above cause on the 15th day of April, 1936, and thereafter plaintiff having appealed, the United States Circuit Court of Appeals - Ninth Circuit - issued, on the 19th day of October, 1939, its Mandate, Order and Decree reversing in certain respects the trder and Decree of this Court entered herein, as aforesaid, on April 15, 1936, and Plaintiff having duly filed and noticed its Motion for an order directine the Clerk to file said Writ of Mandate and for an order amending said final Decree to conform with said \-lrit, and It appearing to the Court that plaintiff and defendants, through their respective attorneys, desire to clarify certain other provisions of the said Decree entered herein on April 15, 1936 as aforesaid, in order that the same will conform to the record, and ( Plaintiff and defendants, through their respec tive attorneys, having presented to this Court a stipulation in writing, s i gne d b y a 11 of the attorneys now of record, that the Court may enter the following ,Order, and good cause appearing therefor. IT IS ORDERED that the Clerk of this Court be, and he is hereby directed ,to file the Mandate, Order and Decree issued by the United States Circuit Court of Appeals - Ninth Circuit - on the 19th day of October, 1939 and received by the Clerk of this Court on October 22, 1939, and IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that page 10 of the final Decree of this Court entered herein on April 15, 1936, be and the same is hereby amended so as to read as follows: "argued before the Court in San Francisco, California and finally submitted on January 10, 1936. -

Carleton E. Watkins Mammoth Plate Photograph Albums: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8t159fr No online items Carleton E. Watkins Mammoth Plate Photograph Albums: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Suzanne Oatey. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Photo Archives 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2019 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Carleton E. Watkins Mammoth 137500; 137501; 137502; 137503 1 Plate Photograph Albums: Finding Aid Overview of the Collection Title: Carleton E. Watkins Mammoth Plate Photograph Albums Dates (inclusive): approximately 1876-1889 Collection Number(s): 137500; 137501; 137502; 137503 Creator: Watkins, Carleton E., 1829-1916 Extent: 174 mammoth plate photographs in 4 albums: albumen prints; size of prints varies, approximately 36 x 53 cm. (14 1/4 x 21 in.); albums each 50 x 69 cm. (19 3/4 x 27 1/4 in.) Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Photo Archives 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: A set of four albums of mammoth plate photographs by American photographer Carleton E. Watkins (1829-1916) made approximately 1876-1889 in California, Nevada, and Arizona. The albums contain 174 photographs and are titled: Photographic Views of Kern County, California; The Central Pacific Railroad and Views Adjacent; Summits of the Sierra; and Arizona and Views Adjacent to the Southern Pacific Railroad. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. Due to the fragility of the albums, access is granted only by permission of the Curator of Photographs. -

Yosemite, Lake Tahoe & the Eastern Sierra

Emerald Bay, Lake Tahoe PCC EXTENSION YOSEMITE, LAKE TAHOE & THE EASTERN SIERRA FEATURING THE ALABAMA HILLS - MAMMOTH LAKES - MONO LAKE - TIOGA PASS - TUOLUMNE MEADOWS - YOSEMITE VALLEY AUGUST 8-12, 2021 ~ 5 DAY TOUR TOUR HIGHLIGHTS w Travel the length of geologic-rich Highway 395 in the shadow of the Sierra Nevada with sightseeing to include the Alabama Hills, the June Lake Loop, and the Museum of Lone Pine Film History w Visit the Mono Lake Visitors Center and Alabama Hills Mono Lake enjoy an included picnic and time to admire the tufa towers on the shores of Mono Lake w Stay two nights in South Lake Tahoe in an upscale, all- suites hotel within walking distance of the casino hotels, with sightseeing to include a driving tour around the north side of Lake Tahoe and a narrated lunch cruise on Lake Tahoe to the spectacular Emerald Bay w Travel over Tioga Pass and into Yosemite Yosemite Valley Tuolumne Meadows National Park with sightseeing to include Tuolumne Meadows, Tenaya Lake, Olmstead ITINERARY Point and sights in the Yosemite Valley including El Capitan, Half Dome and Embark on a unique adventure to discover the majesty of the Sierra Nevada. Born of fire and ice, the Yosemite Village granite peaks, valleys and lakes of the High Sierra have been sculpted by glaciers, wind and weather into some of nature’s most glorious works. From the eroded rocks of the Alabama Hills, to the glacier-formed w Enjoy an overnight stay at a Yosemite-area June Lake Loop, to the incredible beauty of Lake Tahoe and Yosemite National Park, this tour features lodge with a private balcony overlooking the Mother Nature at her best. -

The Walker Basin, Nevada and California: Physical Environment, Hydrology, and Biology

EXHIBIT 89 The Walker Basin, Nevada and California: Physical Environment, Hydrology, and Biology Dr. Saxon E. Sharpe, Dr. Mary E. Cablk, and Dr. James M. Thomas Desert Research Institute May 2007 Revision 01 May 2008 Publication No. 41231 DESERT RESEARCH INSTITUTE DOCUMENT CHANGE NOTICE DRI Publication Number: 41231 Initial Issue Date: May 2007 Document Title: The Walker Basin, Nevada and California: Physical Environment, Hydrology, and Biology Author(s): Dr. Saxon E. Sharpe, Dr. Mary E. Cablk, and Dr. James M. Thomas Revision History Revision # Date Page, Paragraph Description of Revision 0 5/2007 N/A Initial Issue 1.1 5/2008 Title page Added revision number 1.2 “ ii Inserted Document Change Notice 1.3 “ iv Added date to cover photo caption 1.4 “ vi Clarified listed species definition 1.5 “ viii Clarified mg/L definition and added WRPT acronym Updated lake and TDS levels to Dec. 12, 2007 values here 1.6 “ 1 and throughout text 1.7 “ 1, P4 Clarified/corrected tui chub statement; references added 1.8 “ 2, P2 Edited for clarification 1.9 “ 4, P2 Updated paragraph 1.10 “ 8, Figure 2 Updated Fig. 2007; corrected tui chub spawning statement 1.11 “ 10, P3 & P6 Edited for clarification 1.12 “ 11, P1 Added Yardas (2007) reference 1.13 “ 14, P2 Updated paragraph 1.14 “ 15, Figure 3 & P3 Updated Fig. to 2007; edited for clarification 1.15 “ 19, P5 Edited for clarification 1.16 “ 21, P 1 Updated paragraph 1.17 “ 22, P 2 Deleted comma 1.18 “ 26, P1 Edited for clarification 1.19 “ 31-32 Clarified/corrected/rearranged/updated Walker Lake section 1.20 -

Yosemite National Park Foundation Overview

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Yosemite National Park California Contact Information For more information about Yosemite National Park, Call (209) 372-0200 (then dial 3 then 5) or write to: Public Information Office, P.O. Box 577, Yosemite, CA 95389 Park Description Through a rich history of conservation, the spectacular The geology of the Yosemite area is characterized by granitic natural and cultural features of Yosemite National Park rocks and remnants of older rock. About 10 million years have been protected over time. The conservation ethics and ago, the Sierra Nevada was uplifted and then tilted to form its policies rooted at Yosemite National Park were central to the relatively gentle western slopes and the more dramatic eastern development of the national park idea. First, Galen Clark and slopes. The uplift increased the steepness of stream and river others lobbied to protect Yosemite Valley from development, beds, resulting in formation of deep, narrow canyons. About ultimately leading to President Abraham Lincoln’s signing 1 million years ago, snow and ice accumulated, forming glaciers the Yosemite Grant in 1864. The Yosemite Grant granted the at the high elevations that moved down the river valleys. Ice Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove of Big Trees to the State thickness in Yosemite Valley may have reached 4,000 feet during of California stipulating that these lands “be held for public the early glacial episode. The downslope movement of the ice use, resort, and recreation… inalienable for all time.” Later, masses cut and sculpted the U-shaped valley that attracts so John Muir led a successful movement to establish a larger many visitors to its scenic vistas today. -

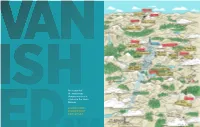

Matthew Greene Were Starting to Understand the Grave the Following Day

VANISHED An account of the mysterious disappearance of a climber in the Sierra Nevada BY MONICA PRELLE ILLUSTRATIONS BY BRETT AFFRUNTI CLIMBING.COM — 61 VANISHED Three months earlier in July, the 39-year-old high school feasted on their arms. They went hiking together often, N THE SMALL SKI TOWN of Mammoth Lakes in math teacher dropped his car off at a Mammoth auto shop even in the really cold winters common to the Northeast. California’s Eastern Sierra, the first snowfall of the for repairs. He was visiting the area for a summer climb- “The ice didn’t slow him down one bit,” Minto said. “I strug- ing vacation when the car blew a head gasket. The friends gled to keep up.” Greene loved to run, competing on the track year is usually a beautiful and joyous celebration. Greene was traveling with headed home as scheduled, and team in high school and running the Boston Marathon a few Greene planned to drive to Colorado to join other friends times as an adult. As the student speaker for his high school But for the family and friends of a missing for more climbing as soon as his car was ready. graduation, Greene urged his classmates to take chances. IPennsylvania man, the falling flakes in early October “I may have to spend the rest of my life here in Mam- “The time has come to fulfill our current goals and to set moth,” he texted to a friend as he got more and more frus- new ones to be conquered later,” he said in his speech. -

Mountain Whitefish Chances for Survival: Better 4 Prosopium Williamsoni

Mountain Whitefish chances for survival: better 4 Prosopium williamsoni ountain whitefish are silvery in color and coarse-scaled with a large and the mackenzie and hudson bay drainages in the arctic. to sustain whatever harvest exists today. mountain whitefish in California and Nevada, they are present in the truckee, should be managed as a native salmonid that is still persisting 1 2 3 4 5 WHITEFISH adipose fin, a small mouth on the underside of the head, a short Carson, and Walker river drainages on the east side of in some numbers. they also are a good indicator of the dorsal fin, and a slender, cylindrical body. they are found the sierra Nevada, but are absent from susan river and “health” of the Carson, Walker, and truckee rivers, as well as eagle lake. lake tahoe and other lakes where they still exist. Whitefish m Mountain Whitefish Distribution throughout western North america. While mountain whitefish are regarded aBundanCe: mountain whitefish are still common in populations in sierra Nevada rivers and tributaries have California, but they are now divided into isolated popula- been fragmented by dams and reservoirs, and are generally as a single species throughout their wide range, a thorough genetic analysis tions. they were once harvested in large numbers by Native scarce in reservoirs. a severe decline in the abundance of americans and commercially harvested in lake tahoe. mountain whitefish in sagehen and prosser Creeks followed would probably reveal distinct population segments. the lahontan population there are still mountain whitefish in lake tahoe, but they the construction of dams on each creek. -

March 2021 Litigation Report

#16B AARON D. FORD JESSICA L. ADAIR Attorney General Chief of Staff KYLE E.N. GEORGE RACHEL J. ANDERSON First Assistant Attorney General General Counsel CHRISTINE JONES BRADY STATE OF NEVADA HEIDI PARRY STERN Second Assistant Attorney General Solicitor General OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL 100 North Carson Street Carson City, Nevada 89701 MEMORANDUM To: Nevada Board of Wildlife Commissioners Tony Wasley, Director, Nevada Department of Wildlife From: Craig Burkett, Senior Deputy Attorney General Date: March 3, 2021 Subject: Litigation Update 1. United States, et al. v. Truckee-Carson Irrigation District, et al. (9th Cir- cuit, San Francisco). An appeal of a judgment against the TCID for excess diversions of water. NDOW appealed to protect its water rights and interests. th The 9 Circuit dismissed NDOW from the case: “[NDOW was] not injured or affected in any way by the judgment on remand from Bell, and thus do not have th standing on appeal.” In a subsequent appeal the 9 Circuit ruled that the “Tribe is entitled to recoup a total of 8,300 acre-feet of water for the years 1985 and 1986.” U.S. v. Truckee-Carson Irrigation Dist., 708 Fed.Appx. 898, 902 (9th Cir. Sept. 13, 2017). TCID recently filed a Motion for Reconsideration based on Kokesh v. Securities and Exchange Commission, 137 S.Ct.1635 (2017). Argument on the Motion was heard February 4, 2019 and TCID’s Motion was denied. Since then, the parties have begun debating the calculations for satisfaction of the prior judgment. The parties submitted briefs explaining their view of the respective calculations and have a hearing sched- uled for September 29, 2020 before Judge Miranda Du. -

Boyhood Days in the Owens Valley 1890-1908

Boyhood Days in the Owens Valley 1890-1908 Beyond the High Sierra and near the Nevada line lies Inyo County, California—big, wild, beautiful, and lonely. In its center stretches the Owens River Valley, surrounded by the granite walls of the Sierra Nevada to the west and the White Mountains to the east. Here the remote town of Bishop hugs the slopes of towering Mount Tom, 13,652 feet high, and here I was born on January 6, 1890. When I went to college, I discovered that most Californians did not know where Bishop was, and I had to draw them a map. My birthplace should have been Candelaria, Nevada, for that was where my parents were living in 1890. My father was an engineer in the Northern Belle silver mine. I was often asked, "Then how come you were born in Bishop?" and I replied, "Because my mother was there." The truth was that after losing a child at birth the year before, she felt Candelaria's medical care was not to be trusted. The decline in the price of silver, the subsequent depression, and the playing out of the mines in Candelaria forced the Albright family to move to Bishop permanently. We had a good life in Bishop. I loved it, was inspired by its aura, and always drew strength and serenity from it. I have no recollection of ever having any bad times. There weren't many special things to do, but what- ever we did, it was on horseback or afoot. Long hours were spent in school.