Flood Page, Michael (2015) the Development of BBC On-Demand Strategy 2003-2007: the Public Value Test and the Iplayer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research & Development White Paper

Research & Development White Paper WHP 293 April 2015 Automatic retrieval of closed captions for web clips from broadcast TV content Chris J. Hughes & Mike Armstrong BRITISH BROADCASTING CORPORATION White Paper WHP 293 Automatic retrieval of closed captions for web clips from broadcast TV content Chris J. Hughes & Mike Armstrong Abstract As broadcasters’ web sites become more media rich it would be prohibitively expensive to manually caption all of the videos provided. However, many of these videos have been clipped from broadcast television and would have been captioned at the point of broadcast. The recent FCC ruling requires all broadcasters to provide closed captions for all ‘straight lift’ video clips that have been broadcast on television from January 2016. From January 2017 captions will be required for ‘Montages’ which consist of multiple clips, and the requirement to caption clips from live or near-live television will apply from July 2017. This paper presents a method of automatically finding a match for a video clip from within a set of off-air television recordings. It then shows how the required set of captions can be autonomously identified, retimed and reformatted for use with IP-delivery. It also shows how captions can be retrieved for each sub-clip within a montage and combined to create a set of captions. Finally it describes how, with a modest amount of human intervention, live captions can be corrected for errors and timing to provide improved captions for video clips presented on the web. This document is based on one originally published at NAB 2015. Because it was written for an American audience it uses the word "captions" throughout in place of "subtitles". -

BBC Fair Trading: Consolidated Group Trading Manual

BBC Fair Trading: Consolidated Group Trading Manual 15 September 2020 Version 4.0 1 Introduction This document sets out the specific arrangements the BBC has implemented to set charges for the goods and services that the BBC commercial subsidiaries (BBC Global News, BBC Studios and BBC Studioworks) obtain from the BBC, and the goods and services the subsidiaries provide to the BBC. It also includes details of goods and services that the BBC provides to third parties outside the BBC Group, and material services that the BBC provides exclusively to third parties. This document – the Consolidated Group Trading Manual – is issued as an update to the Consolidated Group Trading Manual published in July 2019. It includes the following sections for relevant transactions in the 2019/20 financial year: • Table 1: Summary of the BBC’s transfer pricing arrangements with its commercial subsidiaries (and third parties where a good or service is provided to commercial subsidiaries and third parties); • Table 2: Summary of the goods and services of material value the BBC sells to third parties, but not to its commercial subsidiaries; • Table 3: Summary of BBC Commercial Subsidiaries’ transfer pricing with the BBC; • Table 4: Summary of BBC Global News and the BBC‘s content supply arrangements; and • Table 5: Summary of the BBC’s rights licensing to BBC Studios and third parties. The BBC has in place separate processes and procedures for commissioning which apply to BBC Studios’ production division as well as third party producers; 1 these arrangements are not included in this document. Commissioning procedures are subject to Ofcom regulation, which apply to how we treat both third parties and the subsidiaries. -

A Study of R&D in Media

POLITECNICO DI TORINO MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ENGINEERING AND MANAGEMENT MASTER’s DEGREE THESIS A STUDY OF R&D IN MEDIA: A QUALITATIVE CASE STUDY OF BBC R&D AND CRITS Candidate Academic Supervisor Taha Hodroj Marco Cantamessa Academic Year 2018/2019 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENT Education has planted eternal seeds in my heart and mind, I dedicate this thesis to every teacher and professor, who have helped me reach this path; To my first teacher who taught me how to use a pen; to my internship supervisor, Sabino Metta; and to my academic supervisor Marco Cantamessa. I would also like to thank my family and friends, I would have never been able to reach this point in my life if it was not for your support and care. 2 “Open books, Open minds” … 3 ABSTRACT R&D was once done in extensive research laboratories, under the hands of brilliant scientists and engineers. Not anymore. The costs of creating and developing technologies have risen, while profits have declined and innovation life-cycle are shortened. Media companies are now innovating in technology clusters with a joint- effort from lead users. This thesis provides a brief synopsis on the impact of convergence to market scenarios and innovation conditions. It finds that, as media converges, R&D in media will remain important, but must adapt to networked-based innovations. Further on, the thesis empirically studies BBC's R&D and CRITS (Rai) activity and analyses their respective managerial, operational and organisational practices before and after convergence. The case study finds that BBC R&D transitioned its innovation approach towards open innovation, while CRITS is locked in its own competencies due to strong path dependency. -

Think Tanks, Television News and Impartiality

Journalism Studies ISSN: 1461-670X (Print) 1469-9699 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rjos20 Think Tanks, Television News and Impartiality Justin Lewis & Stephen Cushion To cite this article: Justin Lewis & Stephen Cushion (2017): Think Tanks, Television News and Impartiality, Journalism Studies, DOI: 10.1080/1461670X.2017.1389295 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2017.1389295 © 2017 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 26 Oct 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 605 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rjos20 THINK TANKS, TELEVISION NEWS AND IMPARTIALITY The ideological balance of sources in BBC programming Justin Lewis and Stephen Cushion Is the use of think tanks ideologically balanced in BBC news and current affairs programming? This study answers this question empirically by establishing which think tanks are referenced in different BBC programming in 2009 and 2015, and then classifying them according to their ideological aims (either left, right, centrist or non-partisan). We draw on a sample size of over 30,000 BBC news and current affairs programmes in 2009 and 2015 to measure how often these think tanks were men- tioned or quoted. Overall, BBC news reveals a clear preference for non-partisan or centrist think tanks. However, when the Labour Party was in power in 2009, left and right-leaning think tanks received similar levels of coverage, but in 2015, when the Conservative Party was in government, right-leaning think tanks outnumbered left-leaning think tanks by around two to one. -

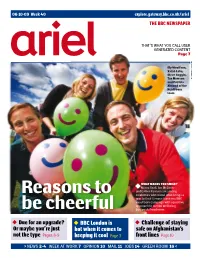

Due for an Upgrade? Or Maybe You're

06·10·09 Week 40 explore.gateway.bbc.co.uk/ariel THE BBC NEWSPAPER THAT’S WHAT YOU CALL USER a GENERATED CONTENT Page 7 photograph Illy Woolfson, : Sarah Lake, mark Steve Goggin, bassett Tae Mawson and Patricia Almond of the Headroom team WHAT MAKES YOU SMILE? ◆Meera Syall, Joe McGann and Esther Rantzen are among Reasons to celebrities who reveal what brings a grin to their famous faces in a BBC Headroom campaign with a positive approach to mental wellbeing. be cheerful bbc.co.uk/headroom ◆ Due for an upgrade? ◆ BBC London is ◆ Challenge of staying Or maybe you’re just hot when it comes to safe on Afghanistan’s not the type Pages 8-9 keeping it cool Page 3 front lines Page 10 > NEWS 2-4 WEEK AT WORK 7 OPINION 10 MAIL 11 JOBS 14 GREEN ROOM 16 < 162 News aa 00·00·08 06·10·09 NEED TO KNOW THE WEEK’S esseNTIALS NEWS BITES a THE BBC has declined to discuss individual tax arrangements Worldwide to the rescue following press reports that it pays Room 2316, White City some star names through service 201 Wood Lane, London W12 7TS companies. Paying presenters 020 8008 4228 u A MonsteR as freelances or through service Managing Editor SUccess could get companies is not a ‘tax dodge’, says Stephen James-Yeoman 02-84222 even bigger, thanks the BBC, adding that if it had doubts Deputy editors to BBC Worldwide about a person’s employment status, which has come to it would consult the Inland Revenue. Sally Hillier 02-26877 the aid of Prime- Cathy Loughran 02-27360 val, ITV’s dinosaur- STRIctLY COME Dancing star Features editor slaying drama. -

Tabletop Storyboarding for Live Film Production

Newcastle University e-prints Date deposited: 24th May 2012 Version of file: Author pre-print Peer Review Status: Peer reviewed Citation for item: Bartindale T, Sheikh A, Taylor N, Wright P, Olivier P. StoryCrate: Tabletop Storyboarding for Live Film Production. In: CHI '12: Proceedings of the 2012 ACM annual conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. 2012, Austin, Texas, USA. Further information on publisher website: http://www.acm.org/ Publisher’s copyright statement: © 2012 ACM. This is the author's version of the work. It is posted here by permission of ACM for your personal use. Not for redistribution. The definitive version was published in CHI '12: Proceedings of the 2012 ACM annual conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, May 2012 at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/2207676.2207700 Always use the definitive version when citing. Use Policy: The full-text may be used and/or reproduced and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not for profit purposes provided that: A full bibliographic reference is made to the original source A link is made to the metadata record in Newcastle E-prints The full text is not changed in any way. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Robinson Library, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, Newcastle upon Tyne. NE1 7RU. Tel. 0191 222 6000 StoryCrate: Tabletop Storyboarding for Live Film Production Tom Bartindale1, Alia Sheikh2, Nick Taylor1, Peter Wright1, Patrick Olivier1 1 Culture Lab 2 BBC Research & Development School of Computing Science Centre House, Newcastle University, UK 56 Wood Lane, {t.l.bartindale,nick.taylor,p.c.wright, London, UK p.l.olivier}@ncl.ac.uk [email protected] ABSTRACT Creating film content for broadcast is a high pressure and complex activity involving multiple experts and highly specialized equipment. -

Changing Sceneries Changing Roles Part Vi Metadata As the Cornerstone of Digital Archiving

CHANGING SCENERIES CHANGING ROLES PART VI METADATA AS THE CORNERSTONE OF DIGITAL ARCHIVING SELECTED PAPERS FROM THE FIAT/IFTA MEDIA MANAGEMENT SEMINAR, HILVERSUM1 2013 CHANGING SCENERIES CHANGING ROLES PART VI METADATA AS THE CORNERSTONE OF DIGITAL ARCHIVING SELECTED PAPERS FROM THE FIAT/IFTA MEDIA MANAGEMENT SEMINAR CHANGING SCENERIES, CHANGING ROLES PART VI HILVERSUM 16TH - 17TH MAY 2013 ORGANISED BY THE FIAT/IFTA MEDIA MANAGEMENT COMMISSION AND BEELD EN GELUID DESIGNED BY AXEL GREEN FOR FIAT/IFTA COVER AND SECTION PHOTOS BY AAD VAN DER VALK PRINTED VERSION BY BEELD EN GELUID AT MULLERVISUAL COMMUNICATION 2013 CONTENTS PREFACE 4 by Annemieke de Jong & Ingrid Veenstra ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 6 by Eva-Lis Green 1. THE NETWORKED SOCIETY 1:1 THE NETWORKED SOCIETY 9 by Nick Ceton 2. LINKED METADATA 2:1 ON APPLES AND COCONUTS 20 by Seth van Hooland 2:2 GEMS: SEMANTICS FOR AUDIOVISUAL DUMMIES 32 by Xavier Jacques-Jourion 3. PRESERVATION METADATA 3:1 PRESERVATION METADATA 44 by Karin Bredenberg 3.2 AV PRESERVATION WORKFLOWS 62 by Annemieke de Jong, Beth Delaney & Daniel Steinmeier 3:3 HELP!: THE LEGAL DEPOSIT FOR ELECTRONIC DOCUMENTS IS HERE 86 by Eva-Lis Green & Kaisa Unander 4. AUTOMATICALLY GENERATED METADATA 4:1 A ROSETTA STONE FOR IMAGE UNDERSTANDING 97 by Cees Snoek 4:2 MOOD BASED TAGGING 108 by Sam Davies 4:3 SPEECH TO TEXT AND SEMANTIC ANALYSIS 126 by Sarah-Haye Aziz, Lorenzo Vassalo & Francesco Veri 5. USER GENERATED METADATA 5:1 THE BBC WORLD SERVICE 136 by Yves Raimond 5:2 RTÉ TWITTER PROJECT 146 by Liam Wylie 6. EPILOGUE 6:1 CONCLUSIONS 156 by Brecht Declercq OBSERVATIONS 162 by Ian Matzen and Jacqui Gupta INDEX OF STILLS 175 PREFACE IN THE DOMAIN of digital archives and digital archiving the concept of ‘metadata’ has become crucial. -

Der Auftrag: Bildung Im Digitalen Zeitalter Public Value Jahresstudie 2016/17 Jahresstudie Public Value Inhalt

STUDIE S DER AUFTRAG: BILDUNG IM DIGITALEN ZEITALTER PUBLIC VALUE JAHRESSTUDIE 2016/17 JAHRESSTUDIE PUBLIC VALUE INHALT 6 RESONANZSPHÄRE DER GESELLSCHAFT? PROF. DR. HARTMUT ROSA UNIVERSITÄT JENA 34 DIE NEUE MACHT DES PUBLIKUMS PROF. DR. BERNHARD PÖRKSEN UNIVERSITÄT TÜBINGEN 47 LABS FOR DEMOCRATIC EDUCATION AND CIVIC DISOBEDIENCE IN POST-TRUTH TIMES? UNIV.-PROF.IN DR.IN KATHARINE SARIKAKIS UNIVERSITÄT WIEN 63 BILDUNG ALS DEMOKRATISCHER AUFTRAG DR.IN MAREN BEAUFORT ÖSTERREICHISCHE AKADEMIE DER WISSENSCHAFTEN 81 SCHMACKL SCHMACKL BUNZ BUNZ KLAUDIA WICK DEUTSCHE KINEMATHEK BERLIN 91 DER BILDUNGSAUFTRAG ÖFFENTLICH-RECHTLICHER MEDIEN DR. VOLKER GRASSMUCK MEDIENWISSENSCHAFTLER PUBLIC VALUE 2017 DIE 5 QUALITÄTSDIMENSIONEN INDIVIDUELLER WERT GESELLSCHAFTSWERT ÖSTERREICHWERT VERTRAUEN VIELFALT IDENTITÄT SERVICE ORIENTIERUNG WERTSCHÖPFUNG UNTERHALTUNG INTEGRATION FÖDERALISMUS WISSEN BÜRGERNÄHE VERANTWORTUNG KULTUR INTERNATIONALER WERT UNTERNEHMENSWERT EUROPA-INTEGRATION INNOVATION GLOBALE PERSPEKTIVE TRANSPARENZ KOMPETENZ Public Value, die gemeinwohlorientierte Qualität der öffentlich-rechtlichen Medienleistung des ORF, wird in insgesamt 18 Kategorien beschrieben, die zu fünf Qualitätsdimensionen zusammengefasst sind. Mehr dazu auf zukunft.ORF.at. DESIGN-KONZEPT: DRUCK: ORF-Druckerei Rosebud, Inc. / www.rosebud-inc.com DESIGN: 1. Auflage, © ORF 2017 ORF Marketing & Creation GmbH & Co KG HERAUSGEBER UND HERSTELLER: Reaktionen, Hinweise Österreichischer Rundfunk, ORF FÜR DEN INHALT VERANTWORTLICH: und Kritik bitte an: Würzburggasse 30, 1136 Wien ORF-Generaldirektion -

Review of the BBC's Research & Development Activity January 2018

Review of the BBC’s Research & Development Activity January 2018 Contents 1. Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 3 2. Introduction and context .............................................................................................................. 10 R&D has contributed to many of the BBC’s most significant achievements .................................... 10 The Government mandate to innovate ............................................................................................ 10 Now is an appropriate time to review the BBC’s R&D activity ......................................................... 12 3. Why R&D matters to the BBC, its audiences and the wider media industry ................................ 14 The BBC’s public service mission drives a distinctive approach to innovation ................................. 14 Delivering for audiences and society in line with the BBC’s public purposes................................... 14 Giving the creative community the tools to fulfil the BBC’s public purposes .................................. 15 Cost-effective innovation and value for money ............................................................................... 16 Delivering value to industry and the UK ........................................................................................... 17 4. Assessment of the impact of BBC R&D, 2007-16 ......................................................................... -

Analysis of Research and Development Investment

Analysis of Research and Development Investment A DotEcon Report for BBC R&D January 2018 DotEcon Ltd 17 Welbeck Street London W1G 9XJ www.dotecon.com Contents Contents 1 Introduction and background ......................................................................................................... 14 1.1 Terms of Reference .................................................................................................................... 14 1.2 Overview of our approach ...................................................................................................... 15 1.3 Structure of this report ............................................................................................................. 20 2 The BBC R&D department ................................................................................................................. 21 2.1 Overview of BBC R&D activities, focus and approach ................................................... 21 2.2 R&D Projects over the most recent Charter Period ........................................................ 25 3 Case study methodology .................................................................................................................. 27 3.1 Choice of case studies ............................................................................................................... 27 3.2 Assessing costs and benefits .................................................................................................. 29 4 Case study findings ............................................................................................................................ -

Der Bildungsauftrag Öffentlich-Rechtlicher Medien

Der Bildungsauftrag öffentlich-rechtlicher Medien Eine Studie im Auftrag des Public-Value-Kompetenzzentrums des ORF * Dr. Volker Grassmuck korrigierte, ergänzte und verlinkte Version 19.11.2017 erschienen in: ORF, Public Value Jahresstudie 2016/17 „Der Auftrag: Bildung im digitalen Zeitalter“, Wien 2017, S. 91-222 * „Bildung ist die gefährlichste Waffe, die Du verwenden kannst, um die Welt zu verändern.“ Gesehen an einer Grundschule auf einer Kaffeeplantage auf São Tomé. 1/125 In der intensiven Debatte über den künftigen Auftrag öffentlich-rechtlicher Medien spielt der Bildungsauftrag erstaunlicherweise fast keine Rolle. Die Studie beginnt mit einem kurzen Überblick über die Definitionen des Bildungsauftrags öffentlich-rechtlicher Medien in Großbritannien, Deutschland und Österreich mit dem Ziel, in dem wenig konturierten Feld zumindest Parameter eines öffentlich-rechtlichen Bildungsauftrages zu identifizieren. Die Meinungs- und Willensbildung des demokratischen Souveräns mit vielfältigen Angeboten zu unterstützen, ist Kern des öffentlich-rechtlichen Auftrags. Daher ist auch für seinen spezifischeren Bildungsauftrag die politische Bildung als eine zentrale Aufgabe zu erwarten, die jedoch in der Literatur selten expliziert wird (z. B. von Naderhirn 2009). Zum einen gibt es Bildungsangebote im engen Sinne für den Vorschulbereich, für Schule, Hochschule und Erwachsenenbildung rsp. lebenslanges Lernen, mit denen die Öffentlich-Rechtlichen die primären Bildungsträger unterstützen und ihr Curriculum begleiten. Daneben verstehen sie ihren Bildungsauftrag in einem weiten Sinne als eine programmliche Querschnittsaufgabe. Es finden sich Hinweise auf die enge Verwandtschaft mit dem Kulturauftrag (Wissenschaftlicher Dienst des Deutschen Bundestages 2006), aber auch mit dem Informationsauftrag (Hoffmann 2016). Nach der Darstellung des regulatorischen und programmlichen Ist-Zustands wird im nächsten Schritt auf die Debatte über die Weiterentwicklung des Auftrags im digitalen Zeitalter fokussiert. -

Cost Benefit Analysis of Innovate UK’S ‘Smart’ R&D Financing Programme7 Determines the Cost Benefit Ratio to Be from 1:4 to 1:5

Analysis of Research and Development Investment A DotEcon Report for BBC R&D January 2018 DotEcon Ltd 17 Welbeck Street London W1G 9XJ www.dotecon.com Contents Contents 1 Introduction and background ......................................................................................................... 14 1.1 Terms of Reference .................................................................................................................... 14 1.2 Overview of our approach ...................................................................................................... 15 1.3 Structure of this report ............................................................................................................. 20 2 The BBC R&D department ................................................................................................................. 21 2.1 Overview of BBC R&D activities, focus and approach ................................................... 21 2.2 R&D Projects over the most recent Charter Period ........................................................ 25 3 Case study methodology .................................................................................................................. 27 3.1 Choice of case studies ............................................................................................................... 27 3.2 Assessing costs and benefits .................................................................................................. 29 4 Case study findings ............................................................................................................................