Derek Johnston 22 April 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Club Sky 328 Newsletter Freesat 306 FEB/MAR 2021 Virgin 445

Freeview 81 Film Club Sky 328 newsletter Freesat 306 FEB/MAR 2021 Virgin 445 You can always call us V 0808 178 8212 Or 01923 290555 Dear Supporters of Film and TV History, It’s been really heart-warming to read all your lovely letters and emails of support about what Talking Pictures TV has meant to you during lockdown, it means so very much to us here in the projectionist’s box, thank you. So nice to feel we have helped so many of you in some small way. Spring is on the horizon, thank goodness, and hopefully better times ahead for us all! This month we are delighted to release the charming filmThe Angel Who Pawned Her Harp, the perfect tonic, starring Felix Aylmer & Diane Cilento, beautifully restored, with optional subtitles plus London locations in and around Islington such as Upper Street, Liverpool Road and the Regent’s Canal. We also have music from The Shadows, dearly missed Peter Vaughan’s brilliant book; the John Betjeman Collection for lovers of English architecture, a special DVD sale from our friends at Strawberry, British Pathé’s 1950 A Year to Remember, a special price on our box set of Together and the crossword is back! Also a brilliant book and CD set for fans of Skiffle and – (drum roll) – The Talking Pictures TV Limited Edition Baseball Cap is finally here – hand made in England! And much, much more. Talking Pictures TV continues to bring you brilliant premieres including our new Saturday Morning Pictures, 9am to 12 midday every Saturday. Other films to look forward to this month include Theirs is the Glory, 21 Days with Vivien Leigh & Laurence Olivier, Anthony Asquith’s Fanny By Gaslight, The Spanish Gardener with Dirk Bogarde, Nijinsky with Alan Bates, Woman Hater with Stewart Granger and Edwige Feuillère,Traveller’s Joy with Googie Withers, The Colour of Money with Paul Newman and Tom Cruise and Dangerous Davies, The Last Detective with Bernard Cribbins. -

13Th Biennial Conference of the International Gothic Association

13th Biennial Conference of the International Gothic Association: Gothic Traditions and Departures Universidad de las Américas Puebla (UDLAP) 18 – 21 July 2017 Conference Draft Programme 1 Conference Schedule Tuesday 18 July 10:00 – 18:00 hrs: Registration, Auditorio Guillermo y Sofía Jenkins (Foyer). 15:00 – 15:30 hrs: Welcome remarks, Auditorio Guillermo y Sofia Jenkins. 15:30 – 16:45 hrs: Opening Plenary Address, Auditorio Guillermo y Sofía Jenkins: Isabella Van Elferen (Kingston University) Dark Sound: Reverberations between Past and Future 16:45 – 18:15 hrs: PARALLEL PANELS SESSION A A1: Scottish Gothic Carol Margaret Davison (University of Windsor): “Gothic Scotland/Scottish Gothic: Theorizing a Scottish Gothic “tradition” from Ossian and Otranto and Beyond” Alison Milbank (University of Nottingham): “Black books and Brownies: The Problem of Mediation in Scottish Gothic” David Punter (University of Bristol): “History, Terror, Tourism: Peter May and Alan Bilton” A2: Gothic Borders: Decolonizing Monsters on the Borderlands Cynthia Saldivar (University of Texas Rio Grande Valley): “Out of Darkness: (Re)Defining Domestic Horror in Americo Paredes's The Shadow” Orquidea Morales (University of Michigan): “Indigenous Monsters: Border Horror Representation of the Border” William A. Calvo-Quirós (University of Michigan): “Border Specters and Monsters of Transformation: The Uncanny history of the U.S.-Mexico Border” A3: Female Gothic Departures Deborah Russell (University of York): “Gendered Traditions: Questioning the ‘Female Gothic’” Eugene -

After Fantastika Programme

#afterfantastika Visit: www.fantastikajournal.com After Fantastika July 6/7th, Lancaster University, UK Schedule Friday 6th 8.45 – 9.30 Registration (Management School Lecture Theatre 11/12) 9.30 – 10.50 Panels 1A & 1B 11.00 – 12.20 Panels 2A, 2B & 2C 12.30 – 1.30 Lunch 1.30 – 2.45 Keynote – Caroline Edwards 3.00 – 4.20 Panels 3A & 3B 4.30 – 6.00 Panels 4A & 4B Saturday 7th 10.30 – 12.00 Panels 5A & 5B 12.00 – 1.00 Lunch 1.00 – 2.15 Keynote – Andrew Tate 2.30 – 3.45 Panels 6A, 6B & 6C 4.00 – 5.00 Roundtable 5.00 Closing Remarks Acknowledgements Thank you to everyone who has helped contribute to either the journal or conference since they began, we massively appreciate your continued support and enthusiasm. We would especially like to thank the Department of English and Creative Writing for their backing – in particular Andrew Tate, Brian Baker, Catherine Spooner and Sara Wasson for their assistance in promoting and supporting these events. A huge thank you to all of our volunteers, chairs, and helpers without which these conferences would not be able to run as smoothly as they always have. Lastly, the biggest thanks of all must go to Chuckie Palmer-Patel who, although sadly not attending the conference in-person, has undoubtedly been an integral part of bringing together such a vibrant and engaging community – while we are all very sad that she cannot be here physically, you can catch her digital presence in panel 6B – technology willing! Thank you Kerry Dodd and Chuckie Palmer-Patel Conference Organisers #afterfantastika Visit: www.fantastikajournal.com -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

Book Reviews.5

Page 58 BOOK REVIEWS “Satan, Thou Art Outdone!” The Pan Book of Horror Stories , Herbert van Thal (ed.), with a new foreword by Johnny Mains (London: Pan Books, 2010) What does it take to truly horrify? What particular qualities do readers look for when they choose a book of horror tales over a book of ghost stories, supernatural thrillers or gothic mysteries? What distinguishes a really horrific story from a tale with the power simply to scare or disturb in a world where one person’s fears and phobias are another person’s ideas of fun? These were questions that the legendary editor Herbert van Thal and publisher Clarence Paget confronted when, in 1957, they began conspiring to put together their first ever collection of horror stories. The result of their shadowy labours, The Pan Book of Horror Stories , was an immediate success and became the premiere volume in a series of collections which were published annually and which appeared, almost without interruption, for the next thirty years. During its lifetime, The Pan Book of Horror Stories became a literary institution as each year, van Thal and Paget did their best to assemble an even more sensational selection of horrifying tales. Many of the most celebrated names in contemporary horror, including Richard Matheson, Robert Bloch and Stephen King, made early appearances between the covers of these anthologies and the cycle proved massively influential on successive waves of horror writers, filmmakers and aficionados. All the same, there are generations of horror fans who have never known the peculiar, queasy pleasure of opening up one of these collections late at night and savouring the creepy imaginings that lie within. -

Bryan Kneale Bryan Kneale Ra

BRYAN KNEALE BRYAN KNEALE RA Foreword by Brian Catling and essays by Andrew Lambirth, Jon Wood and Judith LeGrove PANGOLIN LONDON CONTENTS FOREWORD Another Brimful of Grace by Brian Catling 7 CHAPTER 1 The Opening Years by Andrew Lambirth 23 CHAPTER 2 First published in 2018 by Pangolin London Pangolin London, 90 York Way, London N1 9AG Productive Tensions by Jon Wood 55 E: [email protected] www.pangolinlondon.com ISBN 978-0-9956213-8-1 CHAPTER 3 All rights reserved. Except for the purpose of review, no part of this book may be reproduced, sorted in a Seeing Anew by Judith LeGrove 87 retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Pangolin London © All rights reserved Set in Gill Sans Light BIOGRAPHY 130 Designed by Pangolin London Printed in the UK by Healeys Printers INDEX 134 (ABOVE) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 136 Bryan Kneale, c.1950s (INSIDE COVER) Bryan Kneale with Catalyst Catalyst 1964, Steel Unique Height: 215 cm 4 5 FOREWORD ANOTHER BRIMFUL OF GRACE “BOAYL NAGH VEL AGGLE CHA VEL GRAYSE” BY BRIAN CATLING Since the first draft of this enthusiasm for Bryan’s that is as telling as a storm and as monumental as work, which I had the privilege to write a couple a runic glyph. And makes yet another lens to look of years ago, a whole new wealth of paintings back on a lifetime of distinctively original work. have been made, and it is in their illumination that Notwithstanding, it would be irreverent I keep some of the core material about the life to discuss these works without acknowledging of Bryan Kneale’s extraordinary talent. -

Celluloid Television Culture the Specificity of Film on Television: The

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Celluloid Television Culture The Specificity of Film on Television: the Action-adventure Text as an Example of a Production and Textual Strategy, 1955 – 1978. https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40025/ Version: Full Version Citation: Sexton, Max (2013) Celluloid Television Culture The Speci- ficity of Film on Television: the Action-adventure Text as an Example of a Production and Textual Strategy, 1955 – 1978. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email Celluloid Television Culture The Specificity of Film on Television: the Action-adventure Text as an Example of a Production and Textual Strategy, 1955 – 1978. Max Sexton A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Birkbeck, University of London, 2012. Declaration I hereby declare that the thesis presented by me for examination of the PhD degree is solely my own work, other than where I have clearly indicated. Birkbeck, University of London Abstract of Thesis (5ST) Notes for Candidate: 1. Type your abstract on the other side of this sheet. 2. Use single-spacing typing. Limit your abstract to one side of the sheet. 3. Please submit this copy of your abstract to the Research Student Unit, Birkbeck, University of London, Registry, Malet Street, London, WC1E 7HX, at the same time as you submit copies of your thesis. 4. This abstract will be forwarded to the University Library, which will send this sheet to the British Library and to ASLIB (Association of Special Libraries and Information Bureaux) for publication to Index to Theses . -

Reflected Shadows: Folklore and the Gothic ABSTRACTS

Reflected Shadows: Folklore and the Gothic ABSTRACTS Dr Gail-Nina Anderson (Independent Scholar) [email protected] Dracula’s Cape: Visual Synecdoche and the Culture of Costume. In 1939 Robert Bloch wrote a story called ‘The Cloak’ which took to its extreme a fashion statement already well established in popular culture – vampires wear cloaks. This illustrated paper explores the development of this motif, which, far from having roots in the original vampire lore of Eastern Europe, demonstrates a complex combination of assumptions about vampires that has been created and fed by the fictional representations in literature and film.While the motif relates most immediately to perceptions of class, demonic identity and the supernatural, it also functions within the pattern of nostalgic reference that defines the vampire in modern folklore and popular culture. The cloak belongs to that Gothic hot-spot, the 1890s, but also to Bela Lugosi, to modern Goth culture and to that contemporary paradigm of ready-fit monsters, the Halloween costume shop, taking it, and its vampiric associations, from aristocratic attire to disposable disguise. Biography: Dr Gail-Nina Anderson is a freelance lecturer who runs daytime courses aimed at enquiring adult audiences and delivers a programme of public talks for Newcastle’s Literary and Philosophical Library. She is also a regular speaker at the Folklore Society ‘Legends’ weekends, and in 2013 delivered the annual Katharine Briggs Lecture at the Warburg Institute, on the topic of Fine Art and Folklore. She specialises in the myth-making elements of the Pre-Raphaelite movement and the development of Gothic motifs in popular culture. -

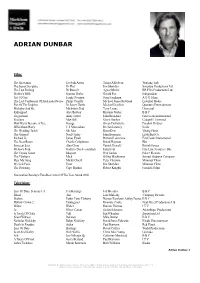

Adrian Dunbar

ADRIAN DUNBAR Film: The Snowman Frederik Aasen Tomas Alfredson Working Title The Secret Scripture Dr Hart Jim Sheridan Scripture Productions Ltd The Last Furlong Dr Russell Agnes Merlet RR Film Productions Ltd Mother's Milk Seamus Dorke Gerald Fox Independent Act Of God Frank O'connor Sean Faughnan A O G Films The Last Confession Of Alexander Pearce Philip Conolly Michael James Rowland Essential Media Eye Of The Dolphin Dr James Hawk Michael D.sellers Quantum Entertainment Mickybo And Me Mickybo's Dad Terry Loane Universal Kidnapped Alex Balfour Brendan Maher B B C Triggerman Andy Jarrett John Bradshaw First Look International Shooters Max Bell Glenn Durfort Catapult / Universal How Harry Became A Tree George Goran Paskaljevic Paradox Pictures Wild About Harry J. J. Macmohan Declan Lowney Scala The Wedding Tackle Mr. Mac Rami Dvir Viking Films The General Noel Curley John Boorman Little Bird Co. Richard Iii James Tyrell Richard Loncraine First Look International The Near Room Charlie Colquhoun David Hayman Bbc Innocent Lies Alan Cross Patrick Dewolf British Screen Widow's Peak Godfrey Doyle-counihan John Irvin Fine Line Features / Bbc The Crying Game Maguire Neil Jordan Palace Pictures The Playboys Mick Gillies Mackinnon Samuel Godwyn Company Hear My Song Micky O'neill Peter Chelsom Miramax Films My Left Foot Peter Jim Sheridan Miramax Films The Dawning Capt. Rankin Robert Knights Ferndale Films Nomination Barclay's Tma Best Actor Of The Year Award 2002 Television: Line Of Duty, Seasons 1-5 Ted Hastings Jed Mecurio B B C Blood Jim Lisa -

Download (15Mb)

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/1294 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. Histories of Telefantasy: the Representation of the Fantastic and the Aesthetics of Television Volume 1 of 2 by Catherine Johnson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television Studies University of Warwick Department of Film and Television Studies April 2002 Contents Volume 1: Illustrations 4 Acknowledgements 10 Declaration 11 Abstract 12 Introduction: 13 Approaching Telefantasy: History, Industry, Aesthetics Chapter 1: 32 Literature Review: Exploring the Discourses of 'Fantasy' and 'Cult' Chapter 2: 56 Spectacle and Intimacy: The Quatermass Serials (BBC, 1953-59) and the Aesthetics of Early British Television Chapter 3: 104 'Serious Entertainment': The Prisoner (ITV, 1967) and Discourses of Quality in 1960s British Television 2 Chpter4: 164 'Regulated Innovation': Star Trek (NBC, 1967-69) and the Commercial Strategies of 1960s US Television Volume 2: Illustrations 223 Chapter 5: 227 Quality Cult Television: The X-Files (Fox, 1993-), Buffy the Vampire Slayer (WB, 1997-) and the Economics and Aesthetics of -

For More Than Seventy Years the Horror Film Has

WE BELONG DEAD FEARBOOK Covers by David Brooks Inside Back Cover ‘Bride of McNaughtonstein’ starring Eric McNaughton & Oxana Timanovskaya! by Woody Welch Published by Buzzy-Krotik Productions All artwork and articles are copyright their authors. Articles and artwork always welcome on horror fi lms from the silents to the 1970’s. Editor Eric McNaughton Design and Layout Steve Kirkham - Tree Frog Communication 01245 445377 Typeset by Oxana Timanovskaya Printed by Sussex Print Services, Seaford We Belong Dead 28 Rugby Road, Brighton. BN1 6EB. East Sussex. UK [email protected] https://www.facebook.com/#!/groups/106038226186628/ We are such stuff as dreams are made of. Contributors to the Fearbook: Darrell Buxton * Darren Allison * Daniel Auty * Gary Sherratt Neil Ogley * Garry McKenzie * Tim Greaves * Dan Gale * David Whitehead Andy Giblin * David Brooks * Gary Holmes * Neil Barrow Artwork by Dave Brooks * Woody Welch * Richard Williams Photos/Illustrations Courtesy of Steve Kirkham This issue is dedicated to all the wonderful artists and writers, past and present, that make We Belong Dead the fantastic magazine it now is. As I started to trawl through those back issues to chose the articles I soon realised that even with 120 pages there wasn’t going to be enough room to include everything. I have Welcome... tried to select an ecleectic mix of articles, some in depth, some short capsules; some serious, some silly. am delighted to welcome all you fans of the classic age of horror It was a hard decision as to what to include and inevitably some wonderful to this first ever We Belong Dead Fearbook! Since its return pieces had to be left out - Neil I from the dead in March 2013, after an absence of some Ogley’s look at the career 16 years, WBD has proved very popular with fans. -

XFR STN: the New Museum's Stone Tape

NEWMUSEUM.ORG The New Museum dedicates its Fifth Floor gallery space to “XFR STN” (Transfer Station), an open-door artist-centered media archiving project. 07/17–09/08/2013 Published by DIRECTOR’S FOREWORD FR STN” initially arose from the need to preserve the Monday/Wednesday/Friday Video Club dis- Conservator of “XFR STN,” he ensures the project operates as close to best practice as possible. We Xtribution project. MWF was a co-op “store” of the artists´ group Colab (Collaborative Projects, are thankful to him and his skilled team of technicians, which includes Rebecca Fraimow, Leeroy Kun Inc.), directed by Alan W. Moore and Michael Carter from 1986–2000, which showed and sold artists’ Young Kang, Kristin MacDonough, and Bleakley McDowell. and independent film and video on VHS at consumer prices. As realized at the New Museum, “XFR STN” will also address the wider need for artists’ access to media services that preserve creative works Staff members from throughout the Museum were called upon for both their specialized skills currently stored in aging and obsolete audiovisual and digital formats. and their untiring enthusiasm for the project. Johanna Burton, Keith Haring Director and Curator of Education and Public Engagement, initiated the project and worked closely with Digital Conser- !e exhibition will produce digitized materials from three distinct repositories: MWF Video Club’s vator at Rhizome, Ben Fino-Radin, the New Museum’s Digital Archivist, Tara Hart, and Associ- collection, which comprises some sixty boxes of diverse moving image materials; the New Museum’s ate Director of Education, Jen Song, on all aspects.