Printed Matter, Inc., the First Decade: 1976-1986

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archived News

Archived News 2007-2008 News articles from 2007-2008 Table of Contents Alumnae Cited for Accomplishments and Sage Salzer ’96................................................. 17 Service................................................................. 5 Porochista Khakpour ’00.................................. 18 Laura Hercher, Human Genetics Faculty............ 7 Marylou Berg ’92 ............................................. 18 Lorayne Carbon, Director of the Early Childhood Meema Spadola ’92.......................................... 18 Center.................................................................. 7 Warren Green ................................................... 18 Hunter Kaczorowski ’07..................................... 7 Debra Winger ................................................... 19 Sara Rudner, Director of the Graduate Program in Dance .............................................................. 7 Melvin Bukiet, Writing Faculty ....................... 19 Rahm Emanuel ’81 ............................................. 8 Anita Brown, Music Faculty ............................ 19 Mikal Shapiro...................................................... 8 Sara Rudner, Dance Faculty ............................. 19 Joan Gill Blank ’49 ............................................. 8 Victoria Hofmo ’81 .......................................... 20 Wayne Sanders, Voice Faculty........................... 8 Students Arrive on Campus.............................. 21 Desi Shelton-Seck MFA ’04............................... 9 Norman -

Artists Books: a Critical Survey of the Literature

700.92 Ar7 1998 artists looks A CRITICAL SURVEY OF THE LITERATURE STEFAN XL I M A ARTISTS BOOKS: A CRITICAL SURVEY OF THE LITERATURE < h'ti<st(S critical survey °f the literature Stefan ^(lima Granary books 1998 New york city Artists Books: A Critical Survey of the Literature by Stefan W. Klima ©1998 Granary Books, Inc. and Stefan W. Klima Printed and bound in The United States of America Paperback original ISBN 1-887123-18-0 Book design by Stefan Klima with additional typographic work by Philip Gallo The text typeface is Adobe and Monotype Perpetua with itc Isadora Regular and Bold for display Cover device (apple/lemon/pear): based on an illustration by Clive Phillpot Published by Steven Clay Granary Books, Inc. 368 Broadway, Suite 403 New York, NY 10012 USA Tel.: (212) 226-3462 Fax: (212) 226-6143 e-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.granarybooks.com Distributed to the trade by D.A.R / Distributed Art Publishers 133 6th Avenue, 2nd Floor New York, NY 10013-1307 Orders: (800) 338-BOOK Tel.: (212) 627—1999 Fax: (212) 627-9484 IP 06 -ta- Adrian & Linda David & Emily & Ray (Contents INTRODUCTION 7 A BEGINNING 12 DEFINITION 21 ART AS A BOOK 41 READING THE BOOK 6l SUCCESSES AND/OR FAILURES 72 BIBLIOGRAPHIC SOURCES 83 LIST OF SOURCES 86 INTRODUCTION Charles Alexander, having served as director of Minnesota Center for Book Arts for twenty months, asked the simple question: “What are the book arts?”1 He could not find a satisfactory answer, though he tried. Somewhere, in a remote corner of the book arts, lay artists books. -

Women in the City Micol Hebron Chapman University, [email protected]

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Art Faculty Articles and Research Art 1-2008 Women in the City Micol Hebron Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/art_articles Part of the Art and Design Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hebron, Micol. “Women in the City”.Flash Art, 41, pp 90, January-February, 2008. Print. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art Faculty Articles and Research by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Women in the City Comments This article was originally published in Flash Art International, volume 41, in January-February 2008. Copyright Flash Art International This article is available at Chapman University Digital Commons: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/art_articles/45 group shows Women in the City S t\:'-: F RA:'-.CISCO in over 50 locations in the Los ments on um screens throughout Museum (which the Guerrilla Angeles region. Nobody walks in the city, presenting images of Girls have been quick to critique LA, but "Women in the City" desirable lu xury items and phrases for its disproportionate holdings of encourages the ear-flaneurs of Los that critique the politics of work by male artists). The four Angeles to put down their cell commodity culture. L{)uisc artists in "Women in the City," phones and lattcs and look for the Lawler's A movie will be shown renowned for their ground billboards, posters, LED screens without the pictures (1979) was re breaking exploration of gender and movie marquis that host the screened in it's original location stereotypes, the power of works in this eJ~;hibition. -

Jenny Holzer, Attempting to Evoke Thought in Society

Simple Truths By Elena, Raphaelle, Tamara and Zofia Introduction • A world without art would not only be dull, ideas and thoughts wouldn’t travel through society or provoke certain reactions on current events and public or private opinions. The intersection of arts and political activism are two fields defined by a shared focus of creating engagement that shifts boundaries, changes relationships and creates new paradigms. Many different artists denounce political issues in their artworks and aim to make large audiences more conscious of different political aspects. One particular artist that focuses on political art is Jenny Holzer, attempting to evoke thought in society. • Jenny Holzer is an American artist who focuses on differing perspectives on difficult political topics. Her work is primarily text-based, using mediums such as paper, billboards, and lights to display it in public spaces. • In order to make her art as accessible to the public, she intertwines aesthetic art with text to portray her political opinions from various points of view. The text strongly reinforces her message, while also leaving enough room for the work to be open to interpretation. Truisms, (1977– 79), among her best-known public works, is a series inspired by Holzer’s experience at Whitney Museum’s Independent Study Program. These form a series of statements, each one representing one individual’s ideology behind a political issue. When presented all together, the public is able to see multiple perspectives on multiple issues. Holzer’s goal in this was to create a less polarized and more tolerant view of our differing viewpoints, normally something that separates us and confines us to one way of thinking. -

Barbara Kruger Born 1945 in Newark, New Jersey

This document was updated February 26, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Barbara Kruger Born 1945 in Newark, New Jersey. Lives and works in Los Angeles and New York. EDUCATION 1966 Art and Design, Parsons School of Design, New York 1965 Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021-2023 Barbara Kruger: Thinking of You, I Mean Me, I Mean You, Art Institute of Chicago [itinerary: Los Angeles County Museum of Art; The Museum of Modern Art, New York] [forthcoming] [catalogue forthcoming] 2019 Barbara Kruger: Forever, Amorepacific Museum of Art (APMA), Seoul [catalogue] Barbara Kruger - Kaiserringträgerin der Stadt Goslar, Mönchehaus Museum Goslar, Goslar, Germany 2018 Barbara Kruger: 1978, Mary Boone Gallery, New York 2017 Barbara Kruger: FOREVER, Sprüth Magers, Berlin Barbara Kruger: Gluttony, Museet for Religiøs Kunst, Lemvig, Denmark Barbara Kruger: Public Service Announcements, Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, Ohio 2016 Barbara Kruger: Empatía, Metro Bellas Artes, Mexico City In the Tower: Barbara Kruger, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC 2015 Barbara Kruger: Early Works, Skarstedt Gallery, London 2014 Barbara Kruger, Modern Art Oxford, England [catalogue] 2013 Barbara Kruger: Believe and Doubt, Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria [catalogue] 2012-2014 Barbara Kruger: Belief + Doubt, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC 2012 Barbara Kruger: Questions, Arbeiterkammer Wien, Vienna 2011 Edition 46 - Barbara Kruger, Pinakothek -

Wedel Art Collective Launch Face Masks Designed by Leading Artists

Wedel Art Collective launch face masks designed by leading artists: Jenny Holzer, Rashid Johnson, Barbara Kruger, Raymond Pettibon, Lorna Simpson and Rosemarie Trockel Left to right, face masks designed by: Rosemarie Trockel; Jenny Holzer; Lorna Simpson; Barbara Kruger; Raymond Pettibon and Rashid Johnson. Courtesy Wedel Art Collective. Wedel Art Collective have collaborated with six international leading artists to produce a set of unique artist-designed face masks, all proceeds from which will be donated to international relief efforts and artist support for those affected by COVID-19. Launching exclusively on MATCHESFASHION from 24 August the project draws upon the power of contemporary art to encourage more people to wear face masks to protect, and support. Each of the participating artists are internationally celebrated for their work addressing some of the most important social and political issues of our times. Through the inspiration of these artists’ work, the limited-edition face masks reflect the artists’ passionate and urgent response to the pandemic, highlighting the need for community action. Artists include: Jenny Holzer (b. 1950, Ohio, USA); Rashid Johnson (b. 1977, Chicago, USA); Barbara Kruger (b. 1975, New Jersey, USA); Raymond Pettibon (b. 1957, Arizona, USA); Lorna Simpson (b. 1960, New York, USA); and Rosemarie Trockel (b. 1952, Schwerte, Germany). Jenny Holzer's face mask taps into the necessity of mask-wearing, reading “You – Me”. “I like to think of my work as useful,” Holzer says “That is a recurrent impulse, when something happens in the world, if I have an idea that be properly responsive… Not necessarily a cure or a solution but at least an offering.” Raymond Pettibon's mask design features Vavoom, a figure inspired by Felix the Cat that he has drawn since the mid-1980s. -

William Burback

THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART ORAL HISTORY PROGRAM INTERVIEW WITH: WILLIAM (BILL) BURBACK (BB) INTERVIEWER: PATTERSON SIMS (PS) LOCATION: THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, PATTERSON SIMS’ OFFICE (OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY DIRECTOR FOR EDUCATION AND RESEARCH SUPPORT) DATE: APRIL 9, 1999 BEGIN TAPE 1, SIDE 1 PS: You‟re a New Yorker [Pause]. BB: Yes, I am a New Yorker. PS: You came here as a junior member of the Photography Department. [Pause] BB: A curatorial intern. It was the New York State Council program. PS: We didn‟t have an internship program then, so you were among the vanguard of interns at the Museum. Now we have a very ambitious intern program. BB: I think it was probably different curatorial departments who took the initiative. There were a number of people who had proceeded... PS: Peter [Galassi] came an intern. BB: I think so, yes, PS: Yes. BB: And [Maria] Morris [Hambourg], at the Met, quite a few people, Anne Tucker, a lot of interesting people. MoMA Archives Oral History: W. Burback page 1 of 29 PS: And it was a part of the national program, NEA, which sent people? BB: No, it was here, the New York Council, but John [Szarkowski] had quite a network, and I met him actually at the Oakland Museum. I was working there as a curatorial assistant in their photography division and I was lucky enough to know him. He was going to Hawaii or someplace like that, probably, though I learned from him in an hour than I had to that point, because the way he saw things and the way he saw that they should be presented were so exciting. -

The WEBER List

the WEBER list ............................................................................................. BEAUX BOOKS 42 Harebell Close Hartley Wintney Hampshire RG27 8TW UK 07783 257 663 [email protected] www.beauxbooks.com The books are listed in chronological order. Please contact us for a full condition report. All titles are offered subject to prior sale. Additional copies of some titles are available but may be subject to a change in price or condition. .................................................................. BEAUX BOOKS ............................................................................................. “It's true to say that I've been searching for my lost youth in my pictures and am basically still looking for it.” (Bruce Weber, Roadside America) the WEBER list Bruce Weber (b.1946) is one of our greatest living photographers. His books, films and exhibitions have placed him at the forefront of American photography for the past 40 years. His ground-breaking work for fashion brands such as Calvin Klein, Ralph Lauren, Versace and Abercrombie & Fitch has changed the face of fashion advertising. Weber's photography is inextricably linked with his own life. His subjects are his friends, and his friends are his subjects. These are real people. They give an honesty to the photographs which have, at the same time, an almost mythical quality. The beautiful, often naked, bodies against the raw American landscape echo a classical, pastoral ideal. This is Weber's American dream – a joyous road-trip around America -

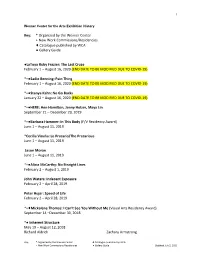

Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue Published by WCA ● Gallery Guide

1 Wexner Center for the Arts Exhibition History Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue published by WCA ● Gallery Guide ●LaToya Ruby Frazier: The Last Cruze February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Sadie Benning: Pain Thing February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Stanya Kahn: No Go Backs January 22 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●HERE: Ann Hamilton, Jenny Holzer, Maya Lin September 21 – December 29, 2019 *+●Barbara Hammer: In This Body (F/V Residency Award) June 1 – August 11, 2019 *Cecilia Vicuña: Lo Precario/The Precarious June 1 – August 11, 2019 Jason Moran June 1 – August 11, 2019 *+●Alicia McCarthy: No Straight Lines February 2 – August 1, 2019 John Waters: Indecent Exposure February 2 – April 28, 2019 Peter Hujar: Speed of Life February 2 – April 28, 2019 *+♦Mickalene Thomas: I Can’t See You Without Me (Visual Arts Residency Award) September 14 –December 30, 2018 *● Inherent Structure May 19 – August 12, 2018 Richard Aldrich Zachary Armstrong Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center ♦ Catalogue published by WCA + New Work Commissions/Residencies ● Gallery Guide Updated July 2, 2020 2 Kevin Beasley Sam Moyer Sam Gilliam Angel Otero Channing Hansen Laura Owens Arturo Herrera Ruth Root Eric N. Mack Thomas Scheibitz Rebecca Morris Amy Sillman Carrie Moyer Stanley Whitney *+●Anita Witek: Clip February 3-May 6, 2018 *●William Kentridge: The Refusal of Time February 3-April 15, 2018 All of Everything: Todd Oldham Fashion February 3-April 15, 2018 Cindy Sherman: Imitation of Life September 16-December 31, 2017 *+●Gray Matters May 20, 2017–July 30 2017 Tauba Auerbach Cristina Iglesias Erin Shirreff Carol Bove Jennie C. -

Comparison of Social Criticism in the Works of Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer Master’S Diploma Thesis

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Bc. Katarína Belejová Comparison of Social Criticism in the Works of Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: doc. PhDr. Tomáš Pospíšil, Dr. 2013 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Bc. Katarína Belejová Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor, doc. PhDr. Tomáš Pospíšil, Dr., for his encouragement, patience and inspirational remarks. I would also like to thank my family for their support. Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................... 5 1. Postmodern Art, Conceptual Art and Social Criticism .............................................. 7 1.1 Social Criticism as a Part of Postmodernity ..................................................................... 7 1.2 Postmodernism, Conceptual Art and Promotion of a Thought .................................. 9 1.2. Importance of Subversion and Parody ........................................................................... 12 1.3 Conceptual Art and Its Audience ...................................................................................... 16 2. American context ..................................................................................................... 21 2.1 The 1980s in the USA ......................................................................................................... -

Catalogue 234 Jonathan A

Catalogue 234 Jonathan A. Hill Bookseller Art Books, Artists’ Books, Book Arts and Bookworks New York City 2021 JONATHAN A. HILL BOOKSELLER 325 West End Avenue, Apt. 10 b New York, New York 10023-8143 home page: www.jonathanahill.com JONATHAN A. HILL mobile: 917-294-2678 e-mail: [email protected] MEGUMI K. HILL mobile: 917-860-4862 e-mail: [email protected] YOSHI HILL mobile: 646-420-4652 e-mail: [email protected] Further illustrations can be seen on our webpage. Member: International League of Antiquarian Booksellers, Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America We accept Master Card, Visa, and American Express. Terms are as usual: Any book returnable within five days of receipt, payment due within thirty days of receipt. Persons ordering for the first time are requested to remit with order, or supply suitable trade references. Residents of New York State should include appropriate sales tax. COVER ILLUSTRATION: © 2020 The LeWitt Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York PRINTED IN CHINA 1. ART METROPOLE, bookseller. [From upper cover]: Catalogue No. 5 – Fall 1977: Featuring european Books by Artists. Black & white illus. (some full-page). 47 pp. Large 4to (277 x 205 mm.), pictorial wrap- pers, staple-bound. [Toronto: 1977]. $350.00 A rare and early catalogue issued by Art Metropole, the first large-scale distributors of artists’ books and publications in North America. This catalogue offers dozens of works by European artists such as Abramovic, Beuys, Boltanski, Broodthaers, Buren, Darboven, Dibbets, Ehrenberg, Fil- liou, Fulton, Graham, Rebecca Horn, Hansjörg Mayer, Merz, Nannucci, Polke, Maria Reiche, Rot, Schwitters, Spoerri, Lea Vergine, Vostell, etc. -

FILM MANUFACTURERS INC. Presents MAPPLETHORPE: LOOK at the PICTURES a Film by Fenton Bailey & Randy Barbato

FILM MANUFACTURERS INC. Presents MAPPLETHORPE: LOOK AT THE PICTURES A film by Fenton Bailey & Randy BArbAto BERLINALE SCREENING SCHEDULE (PREMIERE) Sunday, February 14th at 5:00 PM @ (P&I SCREENING) Sunday, FebruAry 14th At 9:00 PM @ Running Time: 1:48:24 minutes For press materials, please visit: Press ContAct Press ContAct Public Insight Dogwoof Andrea Klasterer Yung Kha Office: +49/ 89/ 78 79 799-12 Office: +44(0)20 7253 6244 Andrea cell: +49 163 680 51 37 Yung cell: +44 7788546706 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] InternAtionAl Sales InternAtionAl Press DOGWOOF [email protected] Vesna Cudic [email protected] / +44 7977 051 577 www.mapplethorpefilm.com www.facebook.com/MapplethorpeFilm www.twitter.com/Mapplethorpedoc www.filminc.com MAPPLETHORPE: LOOK AT THE PICTURES A film by Fenton Bailey & Randy Barbato SHORT SYNOPSIS MAPPLETHORPE: LOOK AT THE PICTURES is the first definitive, feature length portrait of the controversial artist since his untimely death in 1989. A catalyst and an illuminator, but also a magnet for scandal, Robert Mapplethorpe had but one goal: to ‘make it’ as an artist and as an art celebrity. He could not have picked a better time: the Manhattan of Warhol’s Factory, Studio 54, and an era of unbridled hedonistic sexuality. His first solo exhibition in 1976 already unveils his subjects: flowers, portraits and nudes. Mapplethorpe quickly gains notoriety through his explicitly sexual photographs from the gay sadomasochistic scene as well as nude pictures of black men. Directors Fenton Bailey and Randy Barbato were given unrestricted access to Mapplethorpe’s archives for their documentary Mapplethorpe: Look at the Pictures, in which this exceptional artist talks candidly about himself in recently discovered interviews.