Hooper, Janet (2002) a Landscape Given Meaning: an Archaeological Perspective on Landscape History in Highland Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERTHSHIRE POST OFFICES (Updated 22/2/2020)

PERTHSHIRE POST OFFICES (updated 22/2/2020) Aberargie 17-1-1855: BRIDGE OF EARN. 1890 ABERNETHY RSO. Rubber 1899. 7-3-1923 PERTH. Closed 29-11-1969. Aberdalgie 16-8-1859: PERTH. Rubber 1904. Closed 11-4-1959. ABERFELDY 1788: POST TOWN. M.O.6-12-1838. No.2 allocated 1844. 1-4-1857 DUNKELD. S.B.17-2-1862. 1865 HO / POST TOWN. T.O.1870(AHS). HO>SSO 1-4-1918 >SPSO by 1990 >PO Local 31-7-2014. Aberfoyle 1834: PP. DOUNE. By 1847 STIRLING. M.O.1-1-1858: discont.1-1-1861. MO-SB 1-8-1879. No.575 issued 1889. By 4/1893 RSO. T.O.19-11-1895(AYL). 1-8-1905 SO / POST TOWN. 19-1-1921 STIRLING. Abernethy 1837: NEWBURGH,Fife. MO-SB 1-4-1875. No.434 issued 1883. 1883 S.O. T.O.2-1-1883(AHT) 1-4-1885 RSO. No.588 issued 1890. 1-8-1905 SO / POST TOWN. 7-3-1923 PERTH. Closed 30-9-2008 >Mobile. Abernyte 1854: INCHTURE. 1-4-1857 PERTH. 1861 INCHTURE. Closed 12-8-1866. Aberuthven 8-12-1851: AUCHTERARDER. Rubber 1894. T.O.1-9-1933(AAO)(discont.7-8-1943). S.B.9-9-1936. Closed by 1999. Acharn 9-3-1896: ABERFELDY. Rubber 1896. Closed by 1999. Aldclune 11-9-1883: BLAIR ATHOL. By 1892 PITLOCHRY. 1-6-1901 KILLIECRANKIE RSO. Rubber 1904. Closed 10-11-1906 (‘Auldclune’ in some PO Guides). Almondbank 8-5-1844: PERTH. Closed 19-12-1862. Re-estd.6-12-1871. MO-SB 1-5-1877. -

The Post Office Perth Directory

i y^ ^'^•\Hl,(a m \Wi\ GOLD AND SILVER SMITH, 31 SIIG-S: STI^EET. PERTH. SILVER TEA AND COFFEE SERVICES, BEST SHEFFIELD AND BIRMINGHAM (!^lettro-P:a3tteto piateb Crutt mb spirit /tamtjs, ^EEAD BASKETS, WAITEKS, ^NS, FORKS, FISH CARVERS, ci &c. &c. &c. ^cotct) pearl, pebble, arib (STatntgorm leroeller^. HAIR BRACELETS, RINGS, BROOCHES, CHAINS, &c. PLAITED AND MOUNTED. OLD PLATED GOODS RE-FINISHED, EQUAL TO NEW. Silver Plate, Jewellery, and Watches Repaired. (Late A. Cheistie & Son), 23 ia:zc3-i3: sti^eet^ PERTH, MANUFACTURER OF HOSIERY Of all descriptions, in Cotton, Worsted, Lambs' Wool, Merino, and Silk, or made to Order. LADIES' AND GENTLEMEN'S ^ilk, Cotton, anb SEoollen ^\}xxi^ attb ^Mktt^, LADIES' AND GENTLEMEN'S DRAWERS, In Silk, Cotton, Worsted, Merino, and Lambs' Wool, either Kibbed or Plain. Of either Silk, Cotton, or Woollen, with Plain or Ribbed Bodies] ALSO, BELTS AND KNEE-CAPS. TARTAN HOSE OF EVERY VARIETY, Or made to Order. GLOVES AND MITTS, In Silk, Cotton, or Thread, in great Variety and Colour. FLANNEL SHOOTING JACKETS. ® €^9 CONFECTIONER AND e « 41, GEORGE STREET, COOKS FOR ALL KINDS OP ALSO ON HAND, ALL KINDS OF CAKES AND FANCY BISCUIT, j^jsru ICES PTO*a0^ ^^te mmU to ©vto- GINGER BEER, LEMONADE, AND SODA WATER. '*»- : THE POST-OFFICE PERTH DIRECTOEI FOR WITH A COPIOUS APPENDIX, CONTAINING A COMPLETE POST-OFFICE DIRECTORY, AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION. COMPILED AND ARRANGED BY JAMES MAESHALL, POST-OFFICE. WITH ^ pUtt of tl)e OTtts atiti d^nmxonn, ENGEAVED EXPRESSLY FOB THE WORK. PEETH PRINTED FOR THE PUBLISHER BY C. G. SIDEY, POST-OFFICE. -

A Guide to Perth and Kinross Councillors

A Guide to Perth and Kinross Councillors Who’s Who Guide 2017-2022 Key to Phone Numbers: (C) - Council • (M) - Mobile Alasdair Bailey Lewis Simpson Labour Liberal Democrat Provost Ward 1 Ward 2 Carse of Gowrie Strathmore Dennis Melloy Conservative Tel 01738 475013 (C) • 07557 813291 (M) Tel 01738 475093 (C) • 07909 884516 (M) Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Ward 2 Strathmore Angus Forbes Colin Stewart Conservative Conservative Ward 1 Ward 2 Carse of Gowrie Strathmore Tel 01738 475034 (C) • 07786 674776 (M) Email [email protected] Tel 01738 475087 (C) • 07557 811341 (M) Tel 01738 475064 (C) • 07557 811337 (M) Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Provost Depute Beth Pover Bob Brawn Kathleen Baird SNP Conservative Conservative Ward 1 Ward 3 Carse of Gowrie Blairgowrie & Ward 9 Glens Almond & Earn Tel 01738 475036 (C) • 07557 813405 (M) Tel 01738 475088 (C) • 07557 815541 (M) Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Fiona Sarwar Tom McEwan Tel 01738 475086 (C) • 07584 206839 (M) SNP SNP Email [email protected] Ward 2 Ward 3 Strathmore Blairgowrie & Leader of the Council Glens Tel 01738 475020 (C) • 07557 815543 (M) Tel 01738 475041 (C) • 07984 620264 (M) Murray Lyle Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Conservative Caroline Shiers Ward 7 Conservative Strathallan Ward 3 Ward Map Blairgowrie & Glens Tel 01738 475037 (C) • 07557 814916 (M) Tel 01738 475094 (C) • 01738 553990 (W) Email [email protected] Email [email protected] Ward 11 Perth City North Ward 12 Ward 4 Perth City Highland -

The Heart of Scotland

TH E H EART OF S COTLA N D PAINT ED BY SUTTO N PALM ER DESCRIBED BY O PE M CRIEF F A . R H N . O PUBLI SH ED BY 4. SO H O SQUARE ° W A A 59 CH ARLES O O . D M L ND N , BLAC K MCMI " Prefa c e “ BO NNI E SCOTLAND pleased so many readers that it came to be supplemented by another volume dwelling “ ” a the a an d an w m inly on western Highl nds Isl ds, hich was illustrated in a different style to match their Wilder ’ t n the a t a nd mistier features . Such an addi io gave u hor s likeness of Scotland a somewhat lop- sided effect and to balance this list he has prepared a third volume dealing w t a nd e et no t u i h the trimmer rich r, y less pict resque te t t —t at t region of nes visi ed by strangers h is, Per hshire and its e to the Hea rt o bord rs . This is shown be f S cotla nd n as a n t a o , not o ly cont i ing its mos f m us scenery, t e n H d a but as bes bl ndi g ighlan and Lowl nd charms, a nd as having made a focus of the national life and t t t his ory . Pic and Scot, Cel and Sassenach, king and vassal, mailed baron and plaided chief, cateran and farmer, t and n and Jacobi e Hanoveria , gauger smuggler, Kirk a nd e n n o n S cessio , here in tur carried a series of struggles whose incidents should be well known through the ‘ Wa verley Novels . -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

Scottish Coast to Coast

SCOTTISH COAST TO COAST WALK ACROSS THE SCOTTISH HIGHLANDS THE SCOTTISH COAST TO COAST WALK SUMMARY Traverse Scotland from Coast to Coast on foot. Take on a classic journey from Perth to Fort William across the moors, mountains and rivers of the central Scottish Highlands. The Scottish Coast to Coast walk visits charming highland towns, remote hotels, quiet glens and wide open moors. All touched by history, people and stories. The Scottish Coast to Coast Walk starts in the elegant city of Perth and follows the River Tay to Dunkeld and Aberfeldy. The route meanders to Kenmore before heading into the empty, and majestic, countryside of Fortingall, Kinloch Rannoch, Rannoch Station and Kingshouse. At Kingshouse you join the West Highland Way to Kinlochleven and then Fort William, the end of your Scottish Coast to Coast Walk. But the walking is only half the story. On your coast to coast journey you will also discover delicious locally sourced salmon, smoky whiskies, charming highland hotels and the warmest of welcomes. Tour: Scottish Coast to Coast Walk Code: WSSCTC Type: Self-Guided Walking Holiday HIGHLIGHTS Price: See Website Single Supplement: See Website Dates: March to December Traversing the incomparable Rannoch Moor Walking Days: 9 Enjoying a fireside dram at the end of an unforgettable day Nights: 10 Spotting Ben Nevis, which marks the end of your Coast to Coast Start: Perth Finish: Fort William Nine days of wonderful walking through ever-changing landscapes Distance: 118.5 Miles Tucking into a perfectly prepared meal at a remote highland hotel. Grade: Moderate to Strenuous WHY CHOOSE TO WALK THE SCOTTISH COAST TO COAST WITH US? IS IT FOR ME? Macs Adventure is a small, energetic company dedicated to delivering adventure excellence. -

DALLRAOICH Strathtay • Pitlochry • Perthshire DALLRAOICH Strathtay • Pitlochry Perthshire • PH9 0PJ

DALLRAOICH Strathtay • Pitlochry • PerthShire DALLRAOICH Strathtay • Pitlochry PerthShire • Ph9 0PJ A handsome victorian house in the sought after village of Strathtay Aberfeldy 7 miles, Pitlochry 10 miles, Perth 27 miles, Edinburgh 71 miles, Glasgow 84 miles (all distances are approximate) = Open plan dining kitchen, 4 reception rooms, cloakroom/wc 4 Bedrooms (2 en suite), family bathroom Garage/workshop, studio, garden stores EPC = E About 0.58 Acres Savills Perth Earn House Broxden Business Park Lamberkine Drive Perth PH1 1RA [email protected] Tel: 01738 445588 SITUATION Dallraoich is situated on the western edge of the picturesque village of Strathtay in highland Perthshire. The village has an idyllic position on the banks of the River Tay and is characterised by its traditional stone houses. Strathtay has a friendly community with a village shop and post office at its heart. A bridge over the Tay links Strathtay to Grandtully where there is now a choice of places to eat out. Aberfeldy is the nearest main centre and has all essential services, including a medical centre. The town has a great selection of independent shops, cafés and restaurants, not to mention the Birks cinema which as well as screening mainstream films has a popular bar and café and hosts a variety of community activities. Breadalbane Academy provides nursery to sixth year secondary education. Dallraoich could hardly be better placed for enjoying the outdoors. In addition to a 9 hole golf course at Strathtay, there are golf courses at Aberfeldy, Kenmore, Taymouth Castle, Dunkeld and Pitlochry. Various water sports take place on nearby lochs and rivers, with the rapids at Grandtully being popular for canoeing and rafting. -

Scotland: Bruce 286

Scotland: Bruce 286 Scotland: Bruce Robert the Bruce “Robert I (1274 – 1329) the Bruce holds an honored place in Scottish history as the king (1306 – 1329) who resisted the English and freed Scotland from their rule. He hailed from the Bruce family, one of several who vied for the Scottish throne in the 1200s. His grandfather, also named Robert the Bruce, had been an unsuccessful claimant to the Scottish throne in 1290. Robert I Bruce became earl of Carrick in 1292 at the age of 18, later becoming lord of Annandale and of the Bruce territories in England when his father died in 1304. “In 1296, Robert pledged his loyalty to King Edward I of England, but the following year he joined the struggle for national independence. He fought at his father’s side when the latter tried to depose the Scottish king, John Baliol. Baliol’s fall opened the way for fierce political infighting. In 1306, Robert quarreled with and eventually murdered the Scottish patriot John Comyn, Lord of Badenoch, in their struggle for leadership. Robert claimed the throne and traveled to Scone where he was crowned king on March 27, 1306, in open defiance of King Edward. “A few months later the English defeated Robert’s forces at Methven. Robert fled to the west, taking refuge on the island of Rathlin off the coast of Ireland. Edward then confiscated Bruce property, punished Robert’s followers, and executed his three brothers. A legend has Robert learning courage and perseverance from a determined spider he watched during his exile. “Robert returned to Scotland in 1307 and won a victory at Loudon Hill. -

The Military Road from Braemar to the Spittal Of

E MILITARTH Y ROAD FROM BRAEMA E SPITTATH O RT L OF GLEN SHEE by ANGUS GRAHAM, F.S.A.SCOT. THAT the highway from Blairgowrie to Braemar (A 93) follows the line of an old military roa mattea s di commof o r n knowledge, thoug wore hth ofteks i n attributed, wrongly, to Wade; but its remains do not seem to have been studied in detail on FIG. i. The route from Braemar to the Spittal of Glen Shee. Highway A 93 is shown as an interrupted line, and ground above the ajoo-foot contour is dotted the ground, while published notes on it are meagre and difficult to find.1 The present paper is accordingly designed to fill out the story of the sixteen miles between BraemaSpittae th Glef d o l an rn Shee (fig. i). Glen Cluni Gled ean n Beag, wit Cairnwele hth l Pass between them,2 havo en outlinn a histors r it f Fraser1e eFo o yse Ol. e M.G ,d Th , Deeside Road (1921) ff9 . 20 , O.Se Se 2. Aberdeenshiref 6-inco p hma , and edn. (1901), sheets xcvm, cvi, cxi, surveye 186n di d 6an revised in 1900; ditto Perthshire, 2nd edn. (1901), sheets vin SW., xiv SE., xv SW., xv NW. and NE., xxm NE., surveye 186n di revised 2an 1898n deditioi e Th . Nationan no l Grid line t (1964s ye doe t )sno include this area, and six-figure references are consequently taken from the O.S. 1-inch map, yth series, sheet 41 (Braemar)loo-kmn i e ar l . -

A Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols Traci N

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2016 Gender Reflections: a Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols Traci N. Billings University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, European History Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Billings, Traci N., "Gender Reflections: a Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1351. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1351 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENDER REFLECTIONS: A RECONSIDERATION OF PICTISH MIRROR AND COMB SYMBOLS by Traci N. Billings A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Anthropology at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2016 ABSTRACT GENDER REFLECTIONS: A RECONSIDERATION OF PICTISH MIRROR AND COMB SYMBOLS by Traci N. Billings The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2016 Under the Supervision of Professor Bettina Arnold, PhD. The interpretation of prehistoric iconography is complicated by the tendency to project contemporary male/female gender dichotomies into the past. Pictish monumental stone sculpture in Scotland has been studied over the last 100 years. Traditionally, mirror and comb symbols found on some stones produced in Scotland between AD 400 and AD 900 have been interpreted as being associated exclusively with women and/or the female gender. This thesis re-examines this assumption in light of more recent work to offer a new interpretation of Pictish mirror and comb symbols and to suggest a larger context for their possible meaning. -

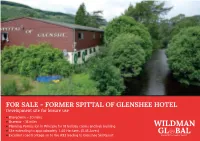

Wildman Global Limited for Themselves and for the Vendor(S) Or Lessor(S) of This Property Whose Agents They Are, Give Notice That: 1

FOR SALE - FORMER SPITTAL OF GLENSHEE HOTEL Development site for leisure use ◆ Blairgowrie – 20 miles ◆ Braemar – 15 miles ◆ Planning Permission in Principle for 18 holiday cabins and hub building WILDMAN ◆ Site extending to approximately 1.40 Hectares (3.45 Acres) GL BAL ◆ Excellent road frontage on to the A93 leading to Glenshee Ski Resort PROPERTY CONSULTANT S LOCATION ACCOMMODATION VIEWING The Spittal of Glenshee lies at the head of Glenshee in the The subjects extend to an approximate area of 1.40 Hectares Strictly by appointment with the sole selling agents. highlands of eastern Perth and Kinross, Scotland. The village has (3.45 Acres). The site plan below illustrates the approximate become a centre for travel, tourism and winter sports in the region. site boundary. SITE CLEARANCE The subjects are directly located off the A93 Trunk Road which The remaining buildings and debris will be removed from the site by leads from Blairgowrie north past the Spittal to the Glenshee Ski PLANNING the date of entry. Centre and on to Braemar. The subjects are sold with the benefit of Planning Permission in Principle (PPiP) from Perth & Kinross Council to develop the entire SERVICES The village also provides a stopping place on the Cateran Trail site to provide 18 holiday cabins, a hub building and associated car ◆ Mains electricity waymarked long distance footpath which provides a 64-mile (103 parking. ◆ Mains water km) circuit in the glens of Perthshire and Angus. ◆ Further information with regard to the planning consent is available Private drainage DESCRIPTION to view on the Perth & Kinross website. -

Notices and Proceedings

THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER FOR THE SCOTTISH TRAFFIC AREA NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 2005 PUBLICATION DATE: 15 April 2013 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 06 May 2013 Correspondence should be addressed to: Scottish Traffic Area Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 249 8142 Website: www.gov.uk The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 29/04/2013 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] NOTICES AND PROCEEDINGS Important Information All correspondence relating to bus registrations and public inquiries should be sent to: Scottish Traffic Area Level 6 The Stamp Office 10 Waterloo Place Edinburgh EH1 3EG The public counter in Edinburgh is open for the receipt of documents between 9.30am and 4pm Monday to Friday. Please note that only payments for bus registration applications can be made at this counter. The telephone number for bus registration enquiries is 0131 200 4927. General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede sections where appropriate. Accuracy of publication – Details published of applications and requests reflect information provided by applicants.