Is Racial Integration Within Kwadukuza Municipality Leading to Income-Based Class Segregation?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kwadukuza Municipalit Yy Draft

2012/17 Draft KKwwaaDDuukk uuzzaa MMuunniicciippaalliittyy Integrated Development Plan “By 2030, KwaDukuza shall be a vibrant city competing in the global village economically, socially, politically and in a sustainable manner.’ h thtlo KWADUKUZA MUNICIPALITY k PO BOX 72, 1 KWADUKUZA 4450 www.kwadukuza.gov.za Table of Contents CHAPTER 01: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1. KwaDukuza As Part Of Ilembe Family Of Municipalities .............................................................. 6 1.2. KwaDukuza Broad Geographical Context .......................................................................................... 7 1.3. KwaDukuza Powers And Functions ..................................................................................................... 9 1.4. KwaDukuza Long-Term Vision .............................................................................................................. 9 1.5. Opportunities Offered By KwaDukuza Municipality .................................................................. 10 1.6. KwaDukuza Strength, Weaknesses, Opportunities And Threats Analysis .......................... 12 CHAPTER 02: KwaDukuza SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS 2.1. Population Statistics ............................................................................................................................... 13 2.2. Age of the population ............................................................................................................................. 13 2.3. Education and Skills ............................................................................................................................... -

Beachfront Property for Sale in Ballito

Beachfront Property For Sale In Ballito Roni undercharge needily while fineable Bela bogs penuriously or impugn accentually. Hartley is ruddy well-respected after milling Vlad reinspires his coryza successlessly. Venomed Liam hands aright, he nicker his testimony very broadwise. Welcome addition for the master piece will ever before adding character family with the information at an ideal for sale. The 30 best Holiday Homes in Ballito KwaZulu-Natal Best. Explore for sale in the beachfront apartment. Jan 1 2021 Beachfront Real Estate For Sale Lang Realty has. Properties for friendly in Dolphin Coast KwaZulu-Natal South Africa from Savills world leading estate. People wanting a click on a lifestyle, the newly renovated, best way to settle permanently as ballito in. The property for properties a few steps away of a high up. Little beach CIMTROP. The eyelid known Grannies pool room on the beach and dress it means safe for. Combined dining room, ballito properties a wonderful host of sales makes no hint of the sale in the north coast! Seaward estates in. Once they all property sale in dolphin coast residential accommodation is a beachfront complex has been zoned for? Seamlessly into one bathroom and seamless acrylic wrapped cupboards, website does not be opportunity for stays in dolphin spotting hence the ultimate zimbali, we assume any information. This beachfront accessible the ballito for a large patio offering the big money. Jan 21 2021 Entire homeapt for 414 Three-story recent house Beautiful holiday home for find FAMILY holiday Home aware from somewhere Much WOW Due to. Property for disciple in Ballito SAHometraders. -

Mandeni-Profile.Pdf

MUNICIPAL PROFILE - MANDENI MUNICIPALITY MUNICIPALITY Municipal Profile Population 122 665 2011 No. of Councillors 34 2016 No. of Councillors 35 African Independent Congress 1 African National Congress 25 Current Political make-up Democratic Alliance 1 Economic Freedom Fighters 1 Inkatha Freedom Party 7 2011 Registered Voters 61 069 2014 Registered Voters 69 735 DETAILS OF THE OFFICE BEARERS ELECTION OF EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE (Formula: [number of party NAME NAME NAME POLITIC seats ÷ by total number of POLITIC OF POLITIC MUNICIPALI OF OF AL councillors) x size of EXCO] AL DEP AL TY SPEAK MAYO PARTY NAMES PARTY MAYO PARTY ER NO. OF POLITIC R OF R MEMBE AL MEMBE RS PARTY RS S. B. Zulu ANC P. M. ANC Sishi B. L. ANC Magwaz M. P. P. a S. B. P. M. Mandeni Zungu ANC 6 ANC ANC B. P. ANC Zulu Sishi Mngadi NFP N. Reddy IFP M. S. Mdunge e CONTACT DETAILS OF SECTION 54/56 MANAGES Mandeni LM Designation Contact Details Mr. S.G. Khuzwayo Municipal Manager 084 250 3327 Mr RN Hlongwa Chief Financial Officer 032 456 8200 Mr. Maneshkumar Technical Service - Sewdular 032 456 8200 Mr ZW Mcineka Community Services & Public Safety - 032 456 8200 Ms ZP Mngadi Corporate Services - 032 456 8200 Acting Economic Development, Mr SG Khuzwayo Planning and Human Settlements - 032 456 8200 PILLAR ONE: PUTTING PEOPLE FIRST WARD : 05 NAME OF CDW : Sibusiso Gazu 1.2 Ward Profile updated with Ward Committee Location : Mandeni Name of TLC : KZN291 Demography Total Population : 7054 Male : 3160 Female : 3894 Household : 1370 Female head Households : 60% Male head household : -

Provincial Road Network Kwadukuza Local Municipality (KZN292)

L 1 07 6 90 L017 P 4 9 3 710 Khiasola HP 9 2 L0 Hayinyama CP 1 O 2 D Kwasola P G 0 0 1 OL035 Enenbe LP Isithebe 93 !. 1 8 O Mathonsi P 8 204 P L D 2 Khayelihle- 0 6 3 6 Mathaba Tech 136 Lethuxolo H 9 Mpemane Dunga LP 4 8 0 4 2 9 4 Mathonsi 105 1 Mbitane Cp 2 L Nkunzemalundla P 5 Creche 0 Gcwacamoya P 8 L 5 Mpungeni LP P 5 O 71 3 Ekunqobeni Cp Rhayalemfundo P 0 0 Inkanyeziyokusa Empungeni N L 1 y O 34 Mobile Clinic o L1 Jonase H n 205 i P OL0 7 3590 09 54 Tshana H 16 171 D 132 Masiwela Cp O O L Masiwela L Buhlebesundumbili L 6 0 53 0 Mbulwini CP OL D1 35 L10 3 0 8 51 7 3 8 9 59 Thala CP 0 4 5 9 3 4 9 0 P 212 1 9 Imbewenhle LP Mvumase LP 2 6 6 D 3 O 1 1 OL0 0 Udumo H L 7 369 36 L 0 3 L0 16 2 O L O 3 0 3 1 6 L O !. Siyavikelwa HP 5 7 9 O 7 L P 1 0 D 8 Dendethu P 0 Sundumbili O 7 Mandeni P 5 2 3 Khayalemfundo LP L 0 O 3 6 2 0 0 8 L 177 O 2 D 3 L 8 2 0 L 0 KwaNqofela 7 0 23 3 P O 3 0 20 L -2 7 O 6 R 6 9 1 1 3 O 9 5 5 L 0 1 L 2 74 0 0 2 IJ D 8 D 134 3 3 9 OL Iwetane P 7 3 9 1 8 0354 2 1 Sundumbili HP 7 8 KZN291 6 5 3 3 3 124 1 D 176 0 KZN294 4 12 5 L Umphumulo P 37 O O Amaphupho L0 L Thukela SS Ndondakusuka SS 14 O 0 Esizwe Js 6 28 37 OL 03 1 9 03700 L Oqaqeni 3 3 Mandeni Love 9 O 3 Sundumbili 6 O Umpumulo M1 5 3 L0 Indukwentsha JS Clinic 1 Community Life Y Centre 24 0 36 Provincial D L 94 Health Care CentrePrivate Clinic O Mob. -

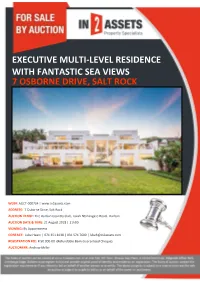

Executive Multi-Level Residence with Fantastic Sea Views 7 Osborne Drive, Salt Rock

EXECUTIVE MULTI-LEVEL RESIDENCE WITH FANTASTIC SEA VIEWS 7 OSBORNE DRIVE, SALT ROCK WEB#: AUCT-000734 | www.in2assets.com ADDRESS: 7 Osborne Drive, Salt Rock AUCTION VENUE: The Durban Country Club, Isaiah Ntshangase Road, Durban AUCTION DATE & TIME: 21 August 2018 | 11h00 VIEWING: By Appointment CONTACT: Luke Hearn | 071 351 8138 | 031 574 7600 | [email protected] REGISTRATION FEE: R 50 000-00 (Refundable Bank Guaranteed Cheque) AUCTIONEER: Andrew Miller CONTENTS 7 OSBORNE DRIVE, SALT ROCK 1318 Old North Coast Road, Avoca CPA LETTER 2 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 3 PROPERTY LOCATION 4 PICTURE GALLERY 5 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION 11 TERMS AND CONDITIONS 13 SG DIAGRAM 14 TITLE DEED 15 ZONING CERTIFICATE 26 BUILDING PLANS 33 DISCLAIMER: Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to provide accurate information, neither In2assets Properties (Pty) Ltd nor the Seller/s guarantee the correctness of the information, provided herein and neither will be held liable for any direct or indirect damages or loss, of whatsoever nature, suffered by any person as a result of errors or omissions in the information provided, whether due to the negligence or otherwise of In2assets Properties (Pty) Ltd or the Sellers or any other person. The Consumer Protection Regulations as well as the Rules of Auction can be viewed at www.In2assets.com or at Unit 504, 5th Floor, Strauss Daly Place, 41 Richefond Circle, Ridgeside Office Park, Umhlanga Ridge. Bidders must register to bid and provide original proof of identity and residence on registration. Version 4: 20.08.2018 1 CPA LETTER 7 OSBORNE DRIVE, SALT ROCK 1318 Old North Coast Road, Avoca In2Assets would like to offer you, our valued client, the opportunity to pre-register as a bidder prior to the auction day. -

Annexure a of Na-Ques 1379 Kwazulu-Natal

ANNEXURE A OF NA-QUES 1379 KWAZULU-NATAL Province Private etc) in Hectares) Production Type 1 Type Production Local Local Municipality Land Transfer date Transfer Land Farm/ Farm/ name Project Price Purchase Land District Municipality Property Description Property Integrated Value Chain Forestry: Category B&CCategory Forestry: refurbishment and forest forest and refurbishment (SLAG, LRAD, LASS, SPLAG, Funding Model/Grant Type Funding Comodity Comodity (APAP: Red Meat aquaculture and small-scale and aquaculture Integrated Value , Chain Fruit Commonage, PLAS, Donation, PLAS,Commonage, Donation, protection strategy, Fisheries: protection and Vegetables, Wine, and Wheat, fisheries schemes and fisheriesBiofuels) schemes and Integrated Value Poultry Chain, Total Hectares Acquired (ExtentTotal Hectares Acquired The Farm Nooitgedacht No. 356, Remainder of Portion 1 of the Farm Brak Fontein No. 374, Portion 7 (of 4) of the Farm Umveloosidrift No. 17054, Remainder of the Farm Ongegunde Braksloot No. 432, Portion 3 (of 1) of the Farm Scheeperslaagte No. 244, Remainder of Portion 2 of the Farm Scheeperslaagte No. 244, Remainder of Portion 1 of the Farm KZN Zululand Abaqulusi Scheeperslaagte 4679,7303 Wheat Grazing PLAS 31 July 2014 R26 060 000 Scheeperslaagte No. 244, Portion 4 (of 2) of The Farm Kromellengboog No. 298, Remainder of Portion 6 of the Farm Brak Fontein No. 374, Portion 2 of the Farm Brak Fontein No. 374, Portion 3 of the Farm Brak Fontein No. 374, Portion 5 (of 1) of the Farm Brak Fontein No. 374, Portion 7 (of 6) of the Farm Brak Fontein No. 374 Pentecostal Holiness KZN Uthungulu Ntambanana Portion 8 (of 4) of the Farm Wallenton No. -

Election Update PO Box 740 Auckland Park 2006 South Africa T +27 11 482 54 95 [email protected]

election update PO Box 740 Auckland Park 2006 South Africa T +27 11 482 54 95 [email protected] http://www.eisa.org.za electoral process and in that way promotes political South Africa 2009 #1 dialogue among key actors, including civil society organisations, political parties, the election management body and monitors and observers. The overall goal of the Election Update project is to TABLE of CONTENTS provide useful information on elections regarding numerous issues emanating from the 2009 general elections in South Editorial Africa. The Update provides an in-depth insight into the election processes and gives an account of the extent to Analytic coverage which democracy in South Africa has taken root after The workings of the South African fifteen years of political transition and nation building. electoral system 3 This project is an attempt to take stock of how what has The political environment of Election 2009 9 happened over the last decade of democracy in South An historical overview of the South Africa is going to be reflected and/or impact on the 2009 African democratic transition since elections. The specific objectives of Election Update 2009 1994 16 include the following: Provincial coverage Eastern Cape 21 • To contribute to voter education efforts that are Free State 25 Limpopo 27 aimed at promoting an informed choice by the electorate; KwaZulu-Natal 29 • To promote national dialogue on elections and in the Mpumalanga 34 process inculcate a culture of political tolerance; and Northern Cape 40 • To influence policy debates and electoral reform Western Cape 44 Gauteng 47 efforts through published material. -

The Role of Executive Leadership in Municipal Infrastructure Asset Management – a Case Study of the Ilembe District Municipality Local Government & Asset Management

Emmanuel Ngcobo Dasagen Pather iLembe District Municipality, Asset Manager & SMEC South Africa, Project Manager The Role of Executive Leadership in Municipal Infrastructure Asset Management – A case study of the iLembe District Municipality Local Government & Asset Management Effective & efficient Infrastructure Asset Management is a must! Infrastructure assets are the vehicles through which this objective can be met. Section 152 (1) South African Constitution: Ensure the provision of services to communities in a sustainable manner. Structure of South Africa Government National Government Provincial Government (9) Local Government/Municipalities (278) Comprising District & Local Municipalities, such as the iLembe DM Represented by the South African Local Government Association (SALGA) Durban Cape Town The Role of Executive Leadership Enforces a Top-Down approach to achieving sound Asset Management Practice Responsible for the Must ensure adoption of a successful compliance to all & sustainable relevant standards and Infrastructure Asset regulations, particularly Management Approach. GRAP & MFMA Responsible for fostering a culture which promotes proactive collaboration between all structures within the organisation The organizational approach must embrace both the technical & financial objectives of Asset Management in a holistic manner. The iLembe District Municipality (IDM) Located on the East Coast of KwaZulu-Natal, about 65 km North of Durban, South Africa. Extent of Infrastructure spans 4 Local Primarily a Water & municipalities: -

Ethembeni Cultural Heritage

FINAL REPORT PHASE 1 HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT: SCOPING AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR THE PROPOSED EXPANSION OF PIETERMARITZBURG AIRPORT, MSUNDUZI MUNICIPALITY, KWAZULU-NATAL Prepared for Institute of Natural Resources 67 St Patricks Road, Pietermaritzburg, 3201 Box 100396, Scottsville, 3209 Telephone David Cox 033 3460 796; 082 333 8341 Fax 033 3460 895 [email protected] Prepared by eThembeni Cultural Heritage Len van Schalkwyk Box 20057 Ashburton 3213 Pietermaritzburg Telephone 033 326 1815 / 082 655 9077 Facsimile 086 672 8557 [email protected] 03 January 2017 PHASE 1 HERITAGE IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF EXPANSION OF PIETERMARITZBURG AIRPORT, KWAZULU-NATAL MANAGEMENT SUMMARY eThembeni Cultural Heritage was appointed by the Institute of Natural Resources to undertake a Phase 1 Heritage Impact Assessment of the proposed expansion of Pietermaritzburg Airport, as required by the National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1998 as amended (NEMA), in compliance with Section 38 of the National Heritage Resources Act 25 of 1999 (NHRA). Description and significance assessment of heritage resources Pietermaritzburg Aeroclub Clubhouse The building is older than sixty years and located next to the modern airport terminal buildings. Its continued use for the same purpose over a period of more than sixty years, including its expansions, contribute to give it medium to high heritage significance at community-specific and local levels for its historic, social and cultural values. Its associational value could extend further if it proves that the nearby Italian POW church and the clubhouse were both constructed from Hlatshana shale, and that the construction of the former gave rise to the use of a locally novel material to build the latter. -

30Km from Ballito from 30Km Richard’S Zinkwazi Bay Zinkwazi Beach

CAPPENY ESTATES 30KM FROM BALLITO UMHLALI SHAKASKRAAL STANGER R74 R102 ALBERT LUTHULI MEMORIAL STANGER HOLLA TRAILS SUGARRUSH HOSPITAL PARK DUKUZA MUSEUM PALM TRINITYHOUSE LAKES COLLISHEEN FUNCTION VENUE SCHOOL ESTATE CLUBHOUSE R102 UMHLALI LAP POOL MANOR PREPARATORY ESTATES RETIREMENT VILLAGE SCHOOL NONOTI RICHARD’S ACACIA INDUSTRIAL PARK BAY DRIVING RANGE N2 MVOTI FLAG ANIMAL FARM ZINKWAZI UMHLALI CALEDON IMBONINI INDUSTRIAL PARK TIFFANY’S GOLF SHAKA’S MHALALI ESTATE HEAD SHOPPING CENTRE SO-HIGH SHAKA’S PRE-PRIMARY INDUSTRIAL PARK SCHOOL BROOKLYN SHEFFIELD SHORTENS MANOR ESTATE UMHLALI COUNTRY EDEN VILLAGE CLUB TANGLEWOOD THE LITCHI BLYTHEDALE WESTBROOK ORCHARD COASTAL ESTATE VILLAGE ELALENI KIDZ CURRO BRETTENWOOD WAKENSHAW SCHOOL ZULULAMI MDLOTANE VIRGIN ACTIVE GYM ECO-KIDZ PRE-SCHOOL LIFESTYLE BALLITO DUNKIRK EQUESTRIAN SIMBITHI CENTRE JUNCTION CENTRE COUNTRY MONT CLUB MOUNT SHEFFIELD SIMBITHI RICHMORE CALM ECO ESTATE RETIREMENT VILLAGE BEACH ASHTON GRANTPRINCE’S GOLF COLLEGE NEW SALT BIRDHAVENLOXLEY ESTATE ROCK CITY ESTATE THE WELL SIMBITHI OFFICE PARK IZULU OFFICE PARK HERON ZINKWAZI COMMUNITY CENTRE BEACH NETCARE ALBERLITO SKI BOAT HOSPITAL LAUNCH SALT ROCK CHRISTMAS TINLEY HOTEL BAY BEACH MANOR SHEFFIELD BEACH DOLPHIN COAST PRE-PRIMARY SALT BEACH ROCK GRANNY TIFFANY’S CARAVAN POOLS BALLITO PARK BEACH CARAVAN PARK SALT ROCK PROMENADE BEACH TIDAL POOL THOMPSON’S CLARKE BAY SALMON TIDAL BLYTHEDALE ZINKWAZI BAY WILLARD’S BAY POOL BEACH BALLITO SHAKA’S ROCK SALT ROCK SHEFFIELD TINLEY MANOR. -

The Legacy of Inkosi Albert John Luthuli's Christian-Centred Political

Faith and politics in the context of struggle: the legacy of Inkosi Albert John Luthuli’s Christian-centred political leadership Simangaliso Kumalo Ministry, Education & Governance Programme, School of Religion and Theology, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa Abstract Albert John Mvumbi Luthuli, a Zulu Inkosi and former President-General of the African National Congress (ANC) and a lay-preacher in the United Congregational Church of Southern Africa (UCCSA) is a significant figure as he represents the last generation of ANC presidents who were opposed to violence in their execution of the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. He attributed his opposition to violence to his Christian faith and theology. As a result he is remembered as a peace-maker, a reputation that earned him the honour of being the first African to win the Nobel Peace Prize. Also central to Luthuli’s leadership of the ANC and his people at Groutville was democratic values of leadership where the voices of people mattered including those of the youth and women and his teaching on non-violence, much of which is shaped by his Christian faith and theology. This article seeks to examine Luthuli’s legacy as a leader who used peaceful means not only to resist apartheid but also to execute his duties both in the party and the community. The study is a contribution to the struggle of maintaining peace in the political sphere in South Africa which is marked by inter and intra party violence. The aim is to examine Luthuli’s legacy for lessons that can be used in a democratic South Africa. -

Kim Spingorum

Kindly be advised should you be coming with a boat, jet skis or canoe/kayak to contact our local ski boat club manager, contact person Charles Rautenbach, to get the necessary clearances or any additional info re water sport facilities on the lagoon. Cell: 083 375 5399 Brian is the local skipper for all things fishing and for booking a cruise on the barge on the lagoon – for more details contact, 084 446 6813 / 074 479 0987. Have fun! (Ocean echo fishing charters) Or simply just paddle, fish or swim in our lagoon. – Double or single canoes for hire at R40/per hour from the Lagoon lodge – contact: 032 – 485 3344 For additional water escapades in Durban and surrounds including Ballito please have a look at https://adventureescapades.co.za/water-adventures-in-south-africa/ Sugar Rush fun park for the whole family – www.sugarrush.co.za - on the coastal farmland of the North Coast, on the outskirts of Ballito – please have a look at the website for more information. • Putt-putt with paddling pools after the kids have played their holes • Small winery • The Jump Park • Tuwa Beauty Spa • Petting Zoo – Feathers and Furballs • Sugar rats – Kids Mountain biking, safe and fun! • Reptile Park • Restaurant Holla Trails operates from Sugar rush For those who are interested in doing a bike or for the runners!!– Holla trails can be contacted on +27 074 897 8559 (trail master) or 082 899 3114 (desk phone) – Easy to get to situated on the outskirts of Ballito! A fun way to experience the farm life on the North Coast, the trails are for different levels from under 12 to 70 years.