Traces of a Libertarian Theory of Punishment Erik Luna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1The Strengths and Limits of Philosophical Anarchism

THE STRENGTHS AND LIMITS OF 1 PHILOSOPHICAL ANARCHISM THE BASIC DEFINITION of state legitimacy as the exclusive right to make, apply, and enforce laws is common, clearly visible in Max Weber and contemporary political philosophy and found less explicitly in the classical contract thinkers.1 A. John Simmons, drawing on Locke, writes that “A state’s (or government’s) legitimacy is the complex moral right it possesses to be the exclusive imposer of binding duties on its sub- jects, to have its subjects comply with these duties, and to use coercion to enforce the duties” (Simmons 2001, 130). Similar definitions—whether vis-à-vis legitimacy or authority—with slight alterations of terms and in conjunction with a series of other ideas and conditions (for example, “authoritativeness,” background criteria, the difference between force and violence) can be found in Robert Paul Wolff (1998, 4), Joseph Raz (2009), Richard Flathman (1980), Leslie Green (1988), David Copp (1999), Hannah Pitkin (1965, 1966), and others. The point is that the justification of state legitimacy and the (corresponding) obligation to obey involve, more often than not, making, applying, and enforcing laws: political power. Often left out of these discussions—with important exceptions—are the real practices of legitimate statehood, and perhaps for good reason. What philosophers who explore the question of legitimacy and authority are most often interested in—for a variety of reasons—is the relation of the individ- ual to the state, that is, whether and to what extent a citizen (or sometimes a noncitizen) has an obligation to obey the state. As Raz notes, part of the explanation for this is that contemporary philosophical interest in questions of political obligation emerged in response to political events in the 1960s (Raz 1981, 105). -

Hume's Theory of Justice*

RMM Vol. 5, 2014, 47–63 Special Topic: Can the Social Contract Be Signed by an Invisible Hand? http://www.rmm-journal.de/ Horacio Spector Hume’s Theory of Justice* Abstract: Hume developed an original and revolutionary theoretical paradigm for explaining the spontaneous emergence of the classic conventions of justice—stable possession, trans- ference of property by consent, and the obligation to fulfill promises. In a scenario of scarce external resources, Hume’s central idea is that the development of the rules of jus- tice responds to a sense of common interest that progressively tames the destructiveness of natural self-love and expands the action of natural moral sentiments. By handling conceptual tools that anticipated game theory for centuries, Hume was able to break with rationalism, the natural law school, and Hobbes’s contractarianism. Unlike natu- ral moral sentiments, the sense of justice is valuable and reaches full strength within a general plan or system of actions. However, unlike game theory, Hume does not assume that people have transparent access to the their own motivations and the inner structure of the social world. In contrast, he blends ideas such as cognitive delusion, learning by experience and coordination to construct a theory that still deserves careful discussion, even though it resists classification under contemporary headings. Keywords: Hume, justice, property, fictionalism, convention, contractarianism. 1. Introduction In the Treatise (Hume 1978; in the following cited as T followed by page num- bers) and the Enquiry concerning the Principles of Morals (Hume 1983; cited as E followed by page numbers)1 Hume discusses the morality of justice by using a revolutionary method that displays the foundation of justice in social utility and the progression of mankind. -

Seven Atheisms

SEVEN ATHEISMS Andrew Walker SEVEN ATHEISMS Exploring the varieties of atheism in John Gray’s book Seven Types of Atheism Andrew Walker Emeritus Professor of Theology, Culture and Education, King’s College London Christian Evidence Society christianevidence.org Text copyright © Andrew Walker 2019 Published by the Christian Evidence Society, London, 2019 christianevidence.com All rights reserved Editing and design: Simon Jenkins Cover photograph by PhotoDu.de / CreativeDomainPhotography.com. Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0) license Contents Introduction 5 The seven atheisms 19th century atheism 6 Secular humanism 8 Science as religion 12 Modern politicial religion 15 God-haters 18 Atheism without progress 22 The atheism of silence 25 Conclusion 27 Index 30 Introduction John Gray’s Seven Types of Atheism (Allen Lane, 2018) is an important book for both religious and non-religious readers. John Gray, who describes himself as an atheist, is nevertheless critical of most versions of atheism. His attitude to atheism is the same as his attitude to certain types of religion. This attitude is predicated upon Gray’s conviction that human beings are intrinsically dissatisfied and unpredictable creatures who can never get along with each other for any length of time. His view is based on a reading of human nature that sails close to the wind of the Christian concept of original sin, and is out of step with most modern forms of atheism. In particular, Gray is allergic to any forms of cultural progress in human behaviour especially if they are couched in positivistic or evolutionary terms. 5 ATHEISM 1 19th century atheism Gray sets out his stall in his first chapter, ‘The New Atheism: A Nineteenth- century Orthodoxy’. -

Yale Law & Policy Review Inter Alia

Essay - Keith Whittington - 09 - Final - 2010.06.29 6/29/2010 4:09:42 PM YALE LAW & POLICY REVIEW INTER ALIA The State of the Union Is a Presidential Pep Rally Keith E. Whittington* Introduction Some people were not very happy with President Barack Obama’s criticism of the U.S. Supreme Court in his 2010 State of the Union Address. Famously, Justice Samuel Alito was among those who took exception to the substance of the President’s remarks.1 The disagreements over the substantive merits of the Citizens United case,2 campaign finance, and whether that particular Supreme Court decision would indeed “open the floodgates for special interests— including foreign corporations—to spend without limits in our elections” are, of course, interesting and important.3 But the mere fact that President Obama chose to criticize the Court, and did so in the State of the Union address, seemed remarkable to some. Chief Justice John Roberts questioned whether the “setting, the circumstances and the decorum” of the State of the Union address made it an appropriate venue for criticizing the work of the Court.4 He was not alone.5 Criticisms of the form of President Obama’s remarks have tended to focus on the idea that presidential condemnations of the Court were “demean[ing]” or “insult[ing]” to the institution or the Justices or particularly inappropriate to * William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Politics, Princeton University. I thank Doug Edlin, Bruce Peabody, and John Woolley for their help on this Essay. 1. Justice Alito, who was sitting in the audience in the chamber of the House of Representatives, was caught by television cameras mouthing “not true” in reaction to President Obama’s characterization of the Citizens United decision. -

Originalism and Constitutional Construction

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2013 Originalism and Constitutional Construction Lawrence B. Solum Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1301 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2307178 82 Fordham L. Rev. 453-537 (2013) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Legal History Commons, and the Legal Theory Commons ORIGINALISM AND CONSTITUTIONAL CONSTRUCTION Lawrence B. Solum* Constitutional interpretation is the activity that discovers the communicative content or linguistic meaning of the constitutional text. Constitutional construction is the activity that determines the legal effect given the text, including doctrines of constitutional law and decisions of constitutional cases or issues by judges and other officials. The interpretation-construction distinction, frequently invoked by contemporary constitutional theorists and rooted in American legal theory in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, marks the difference between these two activities. This Article advances two central claims about constitutional construction. First, constitutional construction is ubiquitous in constitutional practice. The central warrant for this claim is conceptual: because construction is the determination of legal effect, construction always occurs when the constitutional text is applied to a particular legal case or official decision. Although some constitutional theorists may prefer to use different terminology to mark the distinction between interpretation and construction, every constitutional theorist should embrace the distinction itself, and hence should agree that construction in the stipulated sense is ubiquitous. -

The Golden Cord

THE GOLDEN CORD A SHORT BOOK ON THE SECULAR AND THE SACRED ' " ' ..I ~·/ I _,., ' '4 ~ 'V . \ . " ': ,., .:._ C HARLE S TALIAFERR O THE GOLDEN CORD THE GOLDEN CORD A SHORT BOOK ON THE SECULAR AND THE SACRED CHARLES TALIAFERRO University of Notre Dame Press Notre Dame, Indiana Copyright © 2012 by the University of Notre Dame Press Notre Dame, Indiana 46556 www.undpress.nd.edu All Rights Reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Taliaferro, Charles. The golden cord : a short book on the secular and the sacred / Charles Taliaferro. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-268-04238-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-268-04238-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. God (Christianity) 2. Life—Religious aspects—Christianity. 3. Self—Religious aspects—Christianity. 4. Redemption—Christianity. 5. Cambridge Platonism. I. Title. BT103.T35 2012 230—dc23 2012037000 ∞ The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction 1 CHAPTER 1 Love in the Physical World 15 CHAPTER 2 Selves and Bodies 41 CHAPTER 3 Some Big Pictures 61 CHAPTER 4 Some Real Appearances 81 CHAPTER 5 Is God Mad, Bad, and Dangerous to Know? 107 CHAPTER 6 Redemption and Time 131 CHAPTER 7 Eternity in Time 145 CHAPTER 8 Glory and the Hallowing of Domestic Virtue 163 Notes 179 Index 197 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply grateful for the patience, graciousness, support, and encour- agement of the University of Notre Dame Press’s senior editor, Charles Van Hof. -

Christianity, Natural Law and the So-Called Liberal State

Christianity, Natural Law and the So-called Liberal State James Gordley According to the Book of Genesis, “God said, ‘Let us make man in our image, after our likeness.’ So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them.” (Gen. 1:26–7) Here, my former colleague Jeremy Waldron has said, is “a doctrine [that]is enormously attractive for those of us who are open to the idea of religious foundations for human rights.”1 What is special about man is that he is created in the image of God. Waldron noted that “[m]any object to the political use of any deep doctrine of this kind. For some, this is a special case of a Rawlsian commitment to standards of public reason generally.”2 He quotes Rawls: “In discussing constitutional essentials and matters of basic justice we are not to appeal to comprehensive religious or philosophical doctrines” but only to “plain truths now widely accepted, and available, to citizens generally.”3 I will come back to this objection later. Rawls’ claim is particularly important for present purposes since he has said the most about what other people can and cannot say in the public forum. Waldron’s own difficulty is with “the further question of what work [this doctrine] can do.”4 Why does it matter? He quoted Anthony Appiah who said, “[w]e do not have to agree that we are created in the image of God ... to agree that we do not want to be tortured by government officials.”5 Towards the end of his article Waldon noted that “[c]onsistently, for almost the whole of the Christian era imago Dei [the image of God] has been associated with man’s capacity for practical reason...”6 He quoted Thomas Aquinas: “man is united to God by his reason or mind, in which is God’s image.”7 I think if he had pursued this point further he could have answered his question. -

From Liberalisms to Enlightenment's Wake

JOURNAL OF IBERTARIAN TUDIES S L S JL VOLUME 21, NO. 3 (FALL 2007): 79–114 GRAY’S PROGRESS: FROM LIBERALISMS TO ENLIGHTENMENT’S WAKE JEREMY SHEARMUR The progress of that darkness . from its first approach to the period of greatest obscuration. William Robertson, History of the Reign of Charles the Fifth I HAVE KNOWN JOHN Gray for quite a few years, and have long admired his work. We were among the (very few) political theorists in the U.K. who, in the early 1970s, had an interest in the work of Hayek, and more generally in issues relating to classical liberalism. During the 1980s, he emerged as the most powerful and effective theorist of classical liberalism in the U.K., notably through his re- interpretations of John Stuart Mill in Mill on Liberty (1983a), his Hayek and Liberty (1984), and his overview and critical assessment of the lib- eral tradition, Liberalism (1986). We had, over the years, various dis- cussions about Hayek and liberalism—as Gray mentions in his Hayek on Liberty—and in that connection we shared many intellectual con- cerns; notably, with problems about how classical liberalism related to particular traditional cultures, and about the value of lives that did not involve autonomy in any significant sense. Our discussions about these and related matters were occasional, and typically by telephone or at Liberty Fund conferences. In the course of one of these conversations, I suggested to Gray that he might consider col- lecting some of his essays on liberalism into a volume, as he kindly JEREMY SHEARMUR is Reader in Philosophy at the Australian National University. -

Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (In a Constitutional Democracy)

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2013 Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy) Imer Flores Georgetown Law Center, [email protected] Georgetown Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 12-161 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1115 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2156455 Imer Flores, Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy), in LAW, LIBERTY, AND THE RULE OF LAW 77-101 (Imer B. Flores & Kenneth E. Himma eds., Springer Netherlands 2013) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Legislation Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Chapter6 Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy) lmer B. Flores Tse-Kung asked, saying "Is there one word which may serve as a rule of practice for all one's life?" K'ung1u-tzu said: "Is not reciprocity (i.e. 'shu') such a word? What you do not want done to yourself, do not ckJ to others." Confucius (2002, XV, 23, 225-226). 6.1 Introduction Taking the "rule of law" seriously implies readdressing and reassessing the claims that relate it to law and liberty, in general, and to a constitutional democracy, in particular. My argument is five-fold and has an addendum which intends to bridge the gap between Eastern and Western civilizations, -

Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse

John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University Faculty Research Working Papers Series Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse Nov 2003 RWP03-044 The views expressed in the KSG Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or Harvard University. All works posted here are owned and copyrighted by the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism1 Mathias Risse John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University October 25, 2003 1. Left-libertarianism is not a new star on the sky of political philosophy, but it was through the recent publication of Peter Vallentyne and Hillel Steiner’s anthologies that it became clearly visible as a contemporary movement with distinct historical roots. “Left- libertarian theories of justice,” says Vallentyne, “hold that agents are full self-owners and that natural resources are owned in some egalitarian manner. Unlike most versions of egalitarianism, left-libertarianism endorses full self-ownership, and thus places specific limits on what others may do to one’s person without one’s permission. Unlike right- libertarianism, it holds that natural resources may be privately appropriated only with the permission of, or with a significant payment to, the members of society. Like right- libertarianism, left-libertarianism holds that the basic rights of individuals are ownership rights. Left-libertarianism is promising because it coherently underwrites both some demands of material equality and some limits on the permissible means of promoting this equality” (Vallentyne and Steiner (2000a), p 1; emphasis added). -

Reviewing Randy Barnett, Restoring the Lost Constitution: the Presumption of Liberty (2004

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2007 Restoring the Right Constitution? (reviewing Randy Barnett, Restoring the Lost Constitution: The Presumption of Liberty (2004)) Eduardo Peñalver Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Eduardo Peñalver, "Restoring the Right Constitution? (reviewing Randy Barnett, Restoring the Lost Constitution: The Presumption of Liberty (2004))," 116 Yale Law Journal 732 (2007). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EDUARDO M. PENALVER Restoring the Right Constitution? Restoringthe Lost Constitution: The Presumption of Liberty BY RANDY E. BARNETT NEW JERSEY: PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 2004. PP. 384. $49.95 A U T H 0 R. Associate Professor, Cornell Law School. Thanks to Greg Alexander, Rick Garnett, Abner Greene, Sonia Katyal, Trevor Morrison, and Steve Shiffrin for helpful comments and suggestions. 732 Imaged with the Permission of Yale Law Journal REVIEW CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 734 I. NATURAL LAW OR NATURAL RIGHTS? TWO TRADITIONS 737 II. BARNETT'S NONORIGINALIST ORIGINALISM 749 A. Barnett's Argument 749 B. Writtenness and Constraint 752 C. Constraint and Lock-In 756 1. Constraint 757 2. Lock-In 758 D. The Nature of Natural Rights 761 III. REVIVING A PROGRESSIVE NATURALISM? 763 CONCLUSION 766 733 Imaged with the Permission of Yale Law Journal THE YALE LAW JOURNAL 116:73 2 2007 INTRODUCTION The past few decades have witnessed a dramatic renewal of interest in the natural law tradition within philosophical circles after years of relative neglect.' This natural law renaissance, however, has yet to bear much fruit within American constitutional discourse, especially among commentators on the left. -

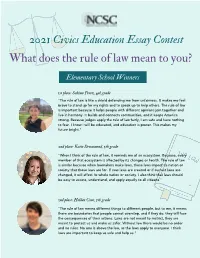

What Does the Rule of Law Mean to You?

2021 Civics Education Essay Contest What does the rule of law mean to you? Elementary School Winners 1st place: Sabina Perez, 4th grade "The rule of law is like a shield defending me from unfairness. It makes me feel brave to stand up for my rights and to speak up to help others. The rule of law is important because it helps people with different opinions join together and live in harmony. It builds and connects communities, and it keeps America strong. Because judges apply the rule of law fairly, I am safe and have nothing to fear. I know I will be educated, and education is power. This makes my future bright." 2nd place: Katie Drummond, 5th grade "When I think of the rule of law, it reminds me of an ecosystem. Because, every member of that ecosystem is affected by its changes or health. The rule of law is similar because when lawmakers make laws, those laws impact its nation or society that those laws are for. If new laws are created or if current laws are changed, it will affect its whole nation or society. I also think that laws should be easy to access, understand, and apply equally to all citizens." 3nd place: Holden Cone, 5th grade "The rule of law means different things to different people, but to me, it means there are boundaries that people cannot overstep, and if they do, they will face the consequences of their actions. Laws are not meant to restrict, they are meant to protect us and make us safer.