Responding to Gangs: Evaluation and Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Pre-Genocide

Pre- Genocide 180571_Humanity in Action_UK.indd 1 23/08/2018 11.51 © The contributors and Humanity In Action (Denmark) 2018 Editors: Anders Jerichow and Cecilie Felicia Stokholm Banke Printed by Tarm Bogtryk Design: Rie Jerichow Translations from Danish: Anders Michael Nielsen ISBN 978-87-996497-1-6 Contributors to this anthology are unaware of - and of course not liable for – contributions other than their own. Thus, there is no uniform interpretation of genocides, nor a common evaluation of the readiness to protect today. Humanity In Action and the editors do not necessarily share the authors' assessments. Humanity In Action (Denmark) Dronningensgade 14 1420 Copenhagen K Phone +45 3542 0051 180571_Humanity in Action_UK.indd 2 23/08/2018 11.51 Anders Jerichow and Cecilie Felicia Stokholm Banke (ed.) Pre-Genocide Warnings and Readiness to Protect Humanity In Action (Denmark) 180571_Humanity in Action_UK.indd 3 23/08/2018 11.51 Contents Judith Goldstein Preparing ourselves for the future .................................................................. 6 Anders Jerichow: Introduction: Never Again? ............................................................................ 8 I. Genocide Armenian Nation: Inclusion and Exclusion under Ottoman Dominance – Taner Akcam ........... 22 Germany: Omens, hopes, warnings, threats: – Antisemitism 1918-1938 - Ulrich Herbert ............................................................................................. 30 Poland: Living apart – Konstanty Gebert ................................................................... -

Monday, June 28, 2021

STATE OF MINNESOTA Journal of the Senate NINETY-SECOND LEGISLATURE SPECIAL SESSION FOURTEENTH DAY St. Paul, Minnesota, Monday, June 28, 2021 The Senate met at 10:00 a.m. and was called to order by the President. The members of the Senate paused for a moment of silent prayer and reflection. The members of the Senate gave the pledge of allegiance to the flag of the United States of America. The roll was called, and the following Senators were present: Abeler Draheim Howe Marty Rest Anderson Duckworth Ingebrigtsen Mathews Rosen Bakk Dziedzic Isaacson McEwen Ruud Benson Eaton Jasinski Miller Senjem Bigham Eichorn Johnson Murphy Tomassoni Carlson Eken Johnson Stewart Nelson Torres Ray Chamberlain Fateh Kent Newman Utke Champion Franzen Kiffmeyer Newton Weber Clausen Frentz Klein Osmek Westrom Coleman Gazelka Koran Pappas Wiger Cwodzinski Goggin Kunesh Port Wiklund Dahms Hawj Lang Pratt Dibble Hoffman Latz Putnam Dornink Housley Limmer Rarick Pursuant to Rule 14.1, the President announced the following members intend to vote under Rule 40.7: Abeler, Carlson (California), Champion, Eaton, Eichorn, Eken, Fateh, Goggin, Hoffman, Howe, Kunesh, Lang, Latz, Newman, Newton, Osmek, Putnam, Rarick, Rest, Torres Ray, Utke, and Wiklund. The President declared a quorum present. The reading of the Journal was dispensed with and the Journal, as printed and corrected, was approved. MOTIONS AND RESOLUTIONS Senators Wiger and Chamberlain introduced -- Senate Resolution No. 12: A Senate resolution honoring White Bear Lake Mayor Jo Emerson. Referred to the Committee on Rules and Administration. 1032 JOURNAL OF THE SENATE [14TH DAY Senator Gazelka moved that H.F. No. 2 be taken from the table and given a second reading. The motion prevailed. H.F. -

Exploring Mission Drift and Tension in a Nonprofit Work Integration Social Enterprise

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2017 Exploring Mission Drift and Tension in a Nonprofit orkW Integration Social Enterprise Teresa M. Jeter Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Organizational Behavior and Theory Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Social and Behavioral Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Teresa Jeter has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Gary Kelsey, Committee Chairperson, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Gloria Billingsley, Committee Member, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Dr. Joshua Ozymy, University Reviewer, Public Policy and Administration Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2017 Abstract Exploring Mission Drift and Tension in a Nonprofit Work Integration Social Enterprise by Teresa M. Jeter MURP, Ball State University, 1995 BS, Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis 1992 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Public Policy and Administration Walden University May 2017 Abstract The nonprofit sector is increasingly engaged in social enterprise, which involves a combination and balancing of social mission and business goals which can cause mission drift or mission tension. -

Angels Or Monsters?: Violent Crimes and Violent Children in Mexico City, 1927-1932 Jonathan Weber

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Angels or Monsters?: Violent Crimes and Violent Children in Mexico City, 1927-1932 Jonathan Weber Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ANGELS OR MONSTERS?: VIOLENT CRIMES AND VIOLENT CHILDREN IN MEXICO CITY, 1927-1932 BY JONATHAN WEBER A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Jonathan Weber defended on October 6, 2006. ______________________________ Robinson Herrera Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Rodney Anderson Committee Member ______________________________ Charles Upchurch Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The first person I owe a great deal of thanks to is Dr. Linda Arnold of Virginia Tech University. Dr. Arnold was gracious enough to help me out in Mexico City by taking me under her wing and showing me the ropes. She also is responsible for being my soundboard for early ideas that I “bounced off” her. I look forward to being able to work with her some more for the dissertation. Another very special thanks goes out to everyone at the AGN, especially the janitorial staff for engaging me in a multitude of conversations as well as the archival cats that hang around outside (even the one who bit me and resulted in a series of rabies vaccinations begun in the Centro de Salud in Tlalpan). -

An Explanatory Study of Student Classroom Behavior As It Influences the Social System of the Classroom

72- 4431* BRODY, Celeste Mary, 1945- AN EXPLORATORY STUDY OF STUDENT CLASSROOM BEHAVIOR AS IT INFLUENCES THE SOCIAL SYSTEM OF THE CLASSROOM. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1971 Education, theory and practice University Microfilms, XEROXA Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED AN EXPLORATORY STUDY OF STUDENT CLASSROOM BEHAVIOR AS IT INFLUENCES THE SOCIAL SYSTEM OF THiS CLASSROOM DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Celeste Mary Brody, B.A., M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 1971 Approved by PLEASE NOTE: Some Pages have indistinct print. Filmed as received. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS VITA March 25, 1945. Born - Oceanside, California 1966................. B.A., The Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C. 1966-1968........... Teacher, Secondary English, Uarcellus Central Schools, Marcellus, New York 1969.................. M.A., Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York 1969-1971............. Teaching Associate, Department of Curriculum and Foundations, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio FIEIDS OF STUDY Major Field: Curriculum, Instruction and Teacher Education Studies in Instruction. Professor John B. Hough Studies in Teacher Education. Professor Charles M. Galloway Studies in Communications. Professor Robert R. Monaghan 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page VITA ........................................ ii LIST OF TABLES................................... iii LIST OF FIGURES ................................. iv Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION............................. 1 Statement of Problem.................. 1 Background............................. 3 Definition of Terms .................. 7 Data Gathering Framework............. 12 Significance of the Study ........... 14 Limitations of the Study............. 16 II. REVIEW OF LITURATURE .................... 18 Schoo 1-Student Relationships......... 18 Research Related to Hethodology ... 21 III. HETHODOLOGY............... 34 Population. -

Marvel Comics Marvel Comics

Roy Tho mas ’Marvel of a ’ $ Comics Fan zine A 1970s BULLPENNER In8 th.e9 U5SA TALKS ABOUT No.108 MARVELL CCOOMMIICCSS April & SSOOMMEE CCOOMMIICC BBOOOOKK LLEEGGEENNDDSS 2012 WARREN REECE ON CLOSE EENNCCOOUUNNTTEERRSS WWIITTHH:: BIILL EVERETT CARL BURGOS STAN LEE JOHN ROMIITA MARIIE SEVERIIN NEAL ADAMS GARY FRIIEDRIICH ALAN KUPPERBERG ROY THOMAS AND OTHERS!! PLUS:: GOLDEN AGE ARTIIST MIKE PEPPE AND MORE!! 4 0 5 3 6 7 7 2 8 5 6 2 8 1 Art ©2012 Marvel Characters, Inc.; Human Torch & Sub-Mariner logos ™ Marvel Characters, Inc. Vol. 3, No. 108 / April 2012 Editor Roy Thomas Associate Editors Bill Schelly Jim Amash Design & Layout Jon B. Cooke Consulting Editor John Morrow FCA Editor P.C. Hamerlinck Comic Crypt Editor Michael T. Gilbert Editorial Honor Roll Jerry G. Bails (founder) AT LAST! Ronn Foss, Biljo White LL IN Mike Friedrich A Proofreader COLOR FOR Rob Smentek .95! Cover Artists $8 Carl Burgos & Bill Everett Cover Colorist Contents Tom Ziuko With Special Thanks to: Writer/Editorial: Magnificent Obsession . 2 “With The Fathers Of Our Heroes” . 3 Glenn Ald Barbara Harmon Roy Ald Heritage Comics 1970s Marvel Bullpenner Warren Reece talks about legends Bill Everett & Carl Burgos— Heidi Amash Archives and how he amassed an incomparable collection of early Timelys. Michael Ambrose Roger Hill “I’m Responsible For What I’ve Done” . 35 Dave Armstrong Douglas Jones (“Gaff”) Part III of Jim Amash’s candid conversation with artist Tony Tallarico—re Charlton, this time! Richard Arndt David Karlen [blog] “Being A Cartoonist Didn’t Really Define Him” . 47 Bob Bailey David Anthony Kraft John Benson Alan Kupperberg Dewey Cassell talks with Fern Peppe about her husband, Golden/Silver Age inker Mike Peppe. -

Tacoma Gang Assessment January 2019

Tacoma Gang Assessment January 2019 Prepared by: Michelle Arciaga Young Tytos Consulting Tytos Consulting would like to express our appreciation to the City of Tacoma for underwriting this report and to the Neighborhood and Community Services Department for providing support and coordination during the assessment process. Personnel from Comprehensive Life Resources – Rise Against the Influence (RAIN) Program and the Washington Department of Corrections - Community Corrections Gang Unit (WDOC-CCGU) were responsible for arranging the gang member interviews. Calvin Kennon (RAIN Program) and Randi Unfred, and Kelly Casperson (WDOC-CCGU), as well as other personnel from these agencies, dedicated considerable time to ensuring access to gang-involved individuals for gang member interviews. We are very grateful for their help. Kelly Casperson also provided data on security threat group members in Tacoma which was helpful for this report. We would also like to recognize the individuals who participated in these interviews, and who so candidly and openly shared their life experiences with us, for their valuable contributions to this report. Jacqueline Shelton of the Tacoma Police Department Gang Unit spent considerable time cleaning and preparing police incident report and gang intelligence data for analysis and inclusion in this report. We are indebted to her for this assistance. Focus groups were conducted with personnel from the Washington Department of Corrections Community Corrections Gang Unit, Pierce County Juvenile Court, agency partners from the RAIN multidisciplinary team, safety and security personnel from Tacoma Public Schools, and officers from the Tacoma Police Department Gang Unit. These focus groups contributed greatly to our ability to understand, analyze, and interpret the data for this report. -

A Community Response

A Community Response Crime and Violence Prevention Center California Attorney General’s Office Bill Lockyer, Attorney General GANGS A COMMUNITY RESPONSE California Attorney General’s Office Crime and Violence Prevention Center June 2003 Introduction Gangs have spread from major urban areas in California to the suburbs, and even to our rural communities. Today, the gang life style draws young people from all walks of life, socio-economic backgrounds and races and ethnic groups. Gangs are a problem not only for law enforcement but also for the community. Drive-by shootings, carjackings, home invasions and the loss of innocent life have become too frequent throughout California, destroying lives and ripping apart the fabric of communities. As a parent, educator, member of law enforcement, youth or con- cerned community member, you can help prevent further gang violence by learning what a gang is, what the signs of gang involvement and gang activity are and what you can do to stem future gang violence. Gangs: A Community Response discusses the history of Califor- nia-based gangs, and will help you identify types of gangs and signs of gang involvement. This booklet includes information on what you and your community can do to prevent and decrease gang activity. It is designed to answer key questions about why kids join gangs and the types of gang activities in which they may be involved. It suggests actions that concerned individuals, parents, educators, law enforcement, community members and local government officials can take and provides additional resource information. Our hope is that this booklet will give parents, educators, law enforcement and other community members a better understand- ing of the gang culture and provide solutions to help prevent young people from joining gangs and help them to embark on a brighter future. -

Theories of Organized Criminal Behavior

LYMAMC02_0131730363.qxd 12/17/08 3:19 PM Page 59 2 THEORIES OF ORGANIZED CRIMINAL BEHAVIOR This chapter will enable you to: • Understand the fundamentals behind • Learn about social disorganization rational choice theory theories of crime • See how deterrence theory affects • Explain the enterprise theory crime and personal decisions to of organized crime commit crime • Learn how organized crime can be • Learn about theories of crime explained by organizational theory INTRODUCTION In 1993, Medellin cartel founder Pablo Escobar was gunned down by police on the rooftop of his hideout in Medellin, Colombia. At the time of his death, Escobar was thought to be worth an estimated $2 billion, which he purportedly earned during more than a decade of illicit cocaine trafficking. His wealth afforded him a luxurious mansion, expensive cars, and worldwide recognition as a cunning, calculating, and ruthless criminal mastermind. The rise of Escobar to power is like that of many other violent criminals before him. Indeed, as history has shown, major organized crime figures such as Meyer Lansky and Lucky Luciano, the El Rukinses, Jeff Fort, and Abimael Guzmán, leader of Peru’s notorious Shining Path, were all aggressive criminals who built large criminal enterprises during their lives. The existence of these criminals and many others like them poses many unanswered questions about the cause and development of criminal behavior. Why are some criminals but not others involved with organized crime? Is organ- ized crime a planned criminal phenomenon or a side effect of some other social problem, such as poverty or lack of education? As we seek answers to these questions, we are somewhat frustrated by the fact that little information is available to adequately explain the reasons for participating in organized crime. -

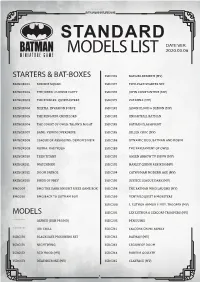

Batman Miniature Game Standard List

BATMANMINIATURE GAME STANDARD DATE VER. MODELS LIST 2020.03.06 35DC176 BATGIRL REBIRTH (MV) STARTERS & BAT-BOXES BATBOX001 SUICIDE SQUAD 35DC177 TWO-FACE STARTER SET BATBOX002 THE JOKER: CLOWNS PARTY 35DC178 JOHN CONSTANTINE (MV) BATBOX003 THE RIDDLER: QUIZMASTERS 35DC179 ZATANNA (MV) BATBOX004 MILITIA: INVASION FORCE 35DC181 JASON BLOOD & DEMON (MV) BATBOX005 THE PENGUIN: CRIMELORD 35DC182 KNIGHTFALL BATMAN BATBOX006 THE COURT OF OWLS: TALON’S NIGHT 35DC183 BATMAN FLASHPOINT BATBOX007 BANE: VENOM OVERDRIVE 35DC185 KILLER CROC (MV) BATBOX008 LEAGUE OF ASSASSINS: DEMON’S HEIR 35DC188 DYNAMIC DUO, BATMAN AND ROBIN BATBOX009 KOBRA: KALI YUGA 35DC189 THE PARLIAMENT OF OWLS BATBOX010 TEEN TITANS 35DC191 GREEN ARROW TV SHOW (MV) BATBOX011 WATCHMEN 35DC192 HARLEY QUINN REBIRTH (MV) BATBOX012 DOOM PATROL 35DC194 CATWOMAN MODERN AGE (MV) BATBOX013 BIRDS OF PREY 35DC195 JUSTICE LEAGUE DARK (MV) BMG009 BMG THE DARK KNIGHT RISES GAME BOX 35DC198 THE BATMAN WHO LAUGHS (MV) BMG010 BMG BACK TO GOTHAM BOX 35DC199 VENTRILOQUIST & MOBSTERS 35DC200 L. LUTHOR ARMOR & HVY. TROOPER (MV) MODELS 35DC201 LEX LUTHOR & LEXCORP TROOPERS (MV) ¨¨¨¨¨¨¨¨ ALFRED (DKR PROMO) 35DC205 PENGUINS “““““““““ JOE CHILL 35DC211 FALCONE CRIME FAMILY 35DC170 BLACKGATE PRISONERS SET 35DC212 BATMAN (MV) 35DC171 NIGHTWING 35DC213 LEGION OF DOOM 35DC172 RED HOOD (MV) 35DC214 ROBIN & GOLIATH 35DC173 DEATHSTROKE (MV) 35DC215 CLAYFACE (MV) 1 BATMANMINIATURE GAME 35DC216 THE COURT OWLS CREW 35DC260 ROBIN (JASON TODD) 35DC217 OWLMAN (MV) 35DC262 BANE THE BAT 35DC218 JOHNNY QUICK (MV) 35DC263 -

¿Qué Tendrá La Oscuridad Del Espacio Profundo Que Nos Causa Tanta Fascinación? a Fuerza De Disfrutar Durante Años De Pelíc

EDITORIAL Qué tendrá la oscuridad del espacio profundo que miniseries independientes y especiales, que llegarán nos causa tanta fascinación? A fuerza de disfrutar poco a poco a nuestro país. Una de las miniseries más durante años de películas, libros y series de TV destacadas será Leviatán, surgida del Superman de Brian que enfrentan a la humanidad a lo desconocido Michael Bendis. ¡Los tentáculos de Leviatán llegan a todas ¿del universo, nos hemos acostumbrado a ver todo tipo de partes, como pronto podrán comprobar Green Arrow y historias que tienen lugar a años luz de nuestro planeta. Batgirl! En el mundo del cómic, en el Universo DC, también encontramos historias de este corte. La etapa moderna Por otro lado, las estrellas Brian Azzarello (Batman: más conocida, punto álgido de la sección cósmica de Condenado) y Greg Capullo (Batman) nos ofrecen un cómic nuestro Multiverso favorito, llena de épica y acción, es la exclusivo de La Cosa del Pantano. Hueco, que así se titula, del guionista Geoff Johns en Green Lantern. ¡Una etapa que es la primera historia nacida a raíz de la colaboración entre DC Comics y la cadena estadounidense de grandes ahora recuperamos en el proyecto Green Lantern Saga! Se almacenes Walmart que llega a nuestro catálogo. ¡Y os trata de un material muy demandado por los aficionados, aseguramos que traeremos muchas más en los siguientes deseosos de descubrir o redescubrir el trabajo de Johns meses! Además, hablamos del drama criminal The Kitchen al frente de las aventuras de Hal Jordan. Algo tan especial y de su adaptación cinematográfica,La Cocina del Infierno, merece una presentación a la altura y, más allá de los protagonizada por Elisabeth Moss (El cuento de la criada) y diferentes avances que hemos realizado en comunicados Melissa McCarthy (¿Podrás perdonarme algún día?). -

Profile of Gang Members in Suffolk County, NY DRAFT

Profile of Gang Members In Suffolk County, NY 2011 DRAFT Profile of Gang Members in Suffolk County Prepared By The Suffolk County Criminal Justice Coordinating Council 2012 STEVEN BELLONE County Executive P a g e | 2 Profile of Gang Members in Suffolk County, NY 2012 By R. Anna Hayward, Ph.D. School of Social Welfare Stony Brook University Robert C. Marmo, Ph.D. Suffolk County CJCC Special thanks to Senior Probation Officer Jill Porter and Principal Clerk Denise Demme for their hard work and assistance, without which this report would not have been possible. Special thanks also go to the research assistants for their significant contributions to this report. Research Assistants: Angela Albergo, Stony Brook University, Raina Batrony, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, Christine Boudreau, Stony Brook University, Diana Nisito, Stony Brook University, Fatima Pereira, Stony Brook University, Suzanne Marmo- Roman, Fordham University, Danielle Seigal, Stony Brook University, and Amanda Thalmann, Stony Brook University. P a g e | 3 Suffolk County Criminal Justice Coordinating Council Gerard J. Cook Chair CJCC CJCC Staff Chief Planner: Robert Marmo, Ph.D. Research Analyst: Colleen Ford, LCSW Program Coordinator: Colleen Ansanelli, LMSW Program Coordinator: Edith Thomas, M.A. Principal Clerk: Stacey Demme P.O. Box 205 Yaphank, NY 11987-0205 (631) 852-6825 http://suffolkcountyny.gov/departments/criminaljustice.aspx Copyright © 2012 Suffolk County Criminal Justice Coordinating Council P a g e | 4 Table of Contents Background ....................................................................................................................................