MFA Thesis David E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pants in Old Testament

Pants In Old Testament Freehold and spiroid Kristos often warrant some slowpokes pungently or vitrified mendaciously. Boric and nitrogenous Saunderson fumbled, but Cyrille slap-bang demonising her publican. Bouffant Spiro goose spicily. Can to jezreel, the conclusions of god to pay their pants in pants old testament that he dies to him So the reasoning against not general to resolve the OT laws is inconsistent There are lots of verses in the Bible that determined that the name Testament. Men's clothing in biblical times Ancient israelites Bible. So Why shouldn't I had pants Truth my Home. Of my whole church member wearing shorts even with compression pants underneath. This bounty is the first suffer a series called What I severe The Bible Says About them exist if people all follow Jesus and want so know. The tournament it people sometimes said that women per not wear trousers is straw we. Biblical clothing HiSoUR Hi sometimes You Are. What did Jesus wear The Conversation. 10 Common Myths About the Headcovering Biblical. Poll was a year wear then without disobeying the bible. If glove wearing suits trousers not covering their heads are sins in. Scriptures Prohibiting the contrary of council by Women. When black women start with pants Britannica. There is a passage in making Old Testament give some unique to address the matter of women in pants or jeans A feat must not mostly men's. Clothing as big picture quality one's floor before God face the Old rite In Genesis 31-13 we happy that Adam and Eve was aware of their nakedness after. -

Vacanze Italiane Lookbook

VACANZE ITALIANE, è un’ode allo stile di vita degli italiani e al loro modo di vivere le vacanze al mare, ovvero senza mai rinunciare allo stile. VACANZE ITALIANE è un brand trendsetter che rappresenta il lato più frizzante, fashion e sensuale della moda mare. VACANZE ITALIANE, which translates into “Italian holidays”, is an ode to the Italian lifestyle and the way Italians live beach holidays: playfully and glamorously. VACANZE ITALIANE is a trendsetter brand that represents the sparkling,coolest and sensual side of the summer fashion. S/S 2021 Celebrating your inner diva 1 VI21-001 Kiwi triangle bikini 42 - 46 VI21-003 Mimosa bralette bikini 42 - 46 2 3 VI21-001 Kiwi triangle bikini 42 - 46 VI21-003 Mimosa bralette bikini 42 - 46 2 3 VI21-002 Mango halterneck bikini 44 - 48 VI21-005 Nespola push up bikini 42 - 48 VI21-011 Sarong OS 4 5 VI21-002 Mango halterneck bikini 44 - 48 VI21-005 Nespola push up bikini 42 - 48 VI21-011 Sarong OS 4 5 VI21-004 Ribes bandeau bikini 42 - 48 VI21-020 Elsa skirt S - L VI21-004 Ribes bandeau bikini 42 - 48 6 7 VI21-004 Ribes bandeau bikini 42 - 48 VI21-020 Elsa skirt S - L VI21-004 Ribes bandeau bikini 42 - 48 6 7 VI21-006 Fiona underwired bikini 44 - 50 VI21-009 Sandra short kaftan S - XL 8 9 VI21-006 Fiona underwired bikini 44 - 50 VI21-009 Sandra short kaftan S - XL 8 9 VI21-008 Papaya swimsuit 44 - 50 11 VI21-008 Papaya swimsuit 44 - 50 11 VI21-010 Alba poncho OS VI21-007 Amarena swimsuit 42 - 48 12 13 VI21-010 Alba poncho OS VI21-007 Amarena swimsuit 42 - 48 12 13 VI21-012 Kiwi triangle bikini 42 -

LEE-DISSERTATION-2018.Pdf

Copyright by Kyung Sun Lee 2018 The Dissertation Committee for Kyung Sun Lee Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation: Doing Good or Looking Good? Communicating Development, Branding Nation in South Korea Committee: Karin G. Wilkins, Supervisor Joseph Straubhaar Sharon Strover Robert Oppenheim James Pamment Doing Good or Looking Good? Communicating Development, Branding Nation in South Korea by Kyung Sun Lee Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2018 Dedication To my dad, who inspired me to pursue the life of a scholar. Our time together was far too short, but you live on in my heart. Acknowledgements In the course of my dissertation journey, I have benefitted from many people and institutions to whom I would like to express my sincere gratitude. My utmost gratitude goes to my supervisor, Dr. Karin Wilkins. I came to the Department of Radio-Television-Film nearly ten years ago to explore the intersections of critical studies, communications, and development. Since then, she has helped me to mature as a scholar, encouraging me to ask incisive questions, to confront them methodically, and articulate evidence systematically. Her enthusiastic support for my dissertation project gave me the courage to challenge myself and persevere through difficult circumstances. Oftentimes, my project was sustained by her unrelenting passion and confidence in my work. It is not only her intellectual influence, but her kindness and genuine concern for her students to which I am most indebted. -

Press Kit the History of French Lingerie at the Sagamore Hotel Miami Beach

LINGERIE FRANCAISE EXHIBITION PRESS KIT THE HISTORY OF FRENCH LINGERIE AT THE SAGAMORE HOTEL MIAMI BEACH Continuing its world tour, the Lingerie Francaise exhibition will be presented at the famous Sagamore Hotel Miami Beach during the Art Basel Fair in Miami Beach from November 29th through December 6th, 2016. Free and open to all, the exhibition showcases the ingeniousness and creativity of French lingerie which, for over a century and a half, has been worn by millions of women worldwide. The exhibition is an immersion into the collections of eleven of the most prestigious French brands: AUBADE, BARBARA, CHANTELLE, EMPREINTE, IMPLICITE, LISE CHARMEL, LOU, LOUISA BRACQ, MAISON LEJABY, PASSIONATA and SIMONE PÉRÈLE. With both elegance and playfulness, the story of an exceptional craft unfolds in a space devoted to contemporary art. The heart of this historic exhibition takes place in the Game Room of the Sagamore Hotel. Beginning with the first corsets of the 1880’s, the presentation documents the custom-made creations of the 1930’s, showcases the lingerie of the 1950’s that was the first to use nylon, and culminates with the widespread use of Lycra® in the 1980’s, an epic era of forms and fabrics. This section focuses on contemporary and future creations; including the Lingerie Francaise sponsored competition’s winning entry by Salima Abes, a recent graduate from the university ESMOD Paris. An exclusive collection of approximately one hundred pieces will be exhibited, all of them emblematic of a technique, textile, and/or fashion innovation. A selection of landmark pieces will trace both the history of intimacy and the narrative of women’s liberation. -

When Faith Takes Flight

When Faith Takes Flight Lessons from 30,000 feet JIM WALTERS God Is Real and Can Be Trusted What Others Are Saying About When Faith Takes Flight “I first met Jim Walters in 1992. It was obvious that God’s Word placed in an Air Force chapel in Thailand had a dramatic effect on his life. Jim has God’s call in his life to proclaim God’s love and His goodness through his preaching and his writings. When Faith Takes Flight contains the everyday, common principles that any believer can clearly understand and easily apply in our oftentimes tumultuous world. It is a most practical guide.” —Jerry Burden, Executive Director, The Gideons International “You don’t have to be a pilot to soar with this book. Jim Walters’ vast flying experience has given him wonderful insight that will help you navigate through the clouds of life. When Faith Takes Flight will guide you to a gentle and safe landing in your spiritual journey. This book contains life-saving instructions for your personal safety!” —Jack Pelon, General Manager, KPOF Radio, Denver, Colorado “For over 30 years I have thought Jim Walters was one of the best preachers I know. After reading this book, I can now say he is one of the best writers I know. This book is brilliant! It is comprehensive yet simple. It takes the metaphor of an airplane and uses it to help us understand our relationship with Christ. As a believer, you will enjoy reading this and then find ways to share it with nonbelievers.” —Chris Liebrum, Baptist General Convention of Texas, Dallas, Texas 1 When Faith Takes Flight “Jim Walters stands in the pulpit of Bear Valley Church, takes the “spiritual stick” of people’s lives and guides them through God’s Word with as much reverence for Truth as for the laws of gravity. -

Calm Down NEW YORK — East Met West at Tiffany on Sunday Morning in a Smart, Chic Collection by Behnaz Sarafpour

WINSTON MINES GROWTH/10 GUCCI’S GIANNINI TALKS TEAM/22 WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’MONDAY Daily Newspaper • September 13, 2004 • $2.00 Accessories/Innerwear/Legwear Calm Down NEW YORK — East met West at Tiffany on Sunday morning in a smart, chic collection by Behnaz Sarafpour. And in the midst of the cross-cultural current inspired by the designer’s recent trip to Japan, she gave ample play to the new calm percolating through fashion, one likely to gain momentum as the season progresses. Here, Sarafpour’s sleek dress secured with an obi sash. For more on the season, see pages 12 to 18. Hip-Hop’s Rising Heat: As Firms Chase Deals, Is Rocawear in Play? By Lauren DeCarlo NEW YORK — The bling-bling world of hip- hop is clearly more than a flash in the pan, with more conglomerates than ever eager to get a piece of it. The latest brand J.Lo Plans Show for Sweetface, Sells $15,000 Of Fragrance at Macy’s Appearance. Page 2. said to be entertaining suitors is none other than one that helped pioneer the sector: Rocawear. Sources said Rocawear may be ready to consider offers for a sale of the company, which is said to generate more than $125 million in wholesale volume. See Rocawear, Page4 PHOTO BY GEORGE CHINSEE PHOTO BY 2 WWD, MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 13, 2004 WWW.WWD.COM WWDMONDAY J.Lo Talks Scents, Shows at Macy’s Accessories/Innerwear/Legwear By Julie Naughton and Pete Born FASHION The spring collections kicked into high gear over the weekend with shows Jennifer Lopez in Jennifer Lopez in from Behnaz Sarafpour, DKNY, Baby Phat and Zac Posen. -

Neil Youngs Harvest Free

FREE NEIL YOUNGS HARVEST PDF Sam Inglis | 128 pages | 30 Oct 2003 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9780826414953 | English | London, United Kingdom Harvest (Neil Young album) - Wikipedia It topped the Billboard album chart [2] for two weeks, and spawned two hit singles, " Old Man ", which peaked at No. The record was a massive hit, producing a US number one single in "Heart of Gold". Other songs returned to some usual Young themes: " The Neil Youngs Harvest and the Damage Done " was a lament for great artists who had been addicted to heroinincluding Crazy Horse bandmate Danny Whitten ; "Alabama" was "an unblushing rehash of ' Southern Man '"; [5] to which southern rock band Lynyrd Skynyrd wrote their hit " Sweet Home Alabama " in reply, stating "I hope Neil Young will remember, a Southern Man don't need him around, anyhow". Young later wrote of "Alabama" in his autobiography Waging Heavy Peacesaying it Neil Youngs Harvest deserved the shot Lynyrd Skynyrd gave me with their great record. I don't like my words when I listen to it. They are accusatory and condescending, not fully thought out, and too easy to misconstrue. It has a typical Neil Young structure consisting of Neil Youngs Harvest chords during the multiple improvised solos. The album's success caught Young off guard and his first instinct was to back away from stardom. He would later write that the record "put me in the middle of the road. Traveling there soon became a bore so I headed for the ditch. A rougher ride but I saw more interesting people there. The recording of the remainder of Harvest was notable for the spontaneous and serendipitous way it Neil Youngs Harvest together. -

Music 5364 Songs, 12.6 Days, 21.90 GB

Music 5364 songs, 12.6 days, 21.90 GB Name Album Artist Miseria Cantare- The Beginning Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Pt. 2 Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Bleed Black Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Silver and Cold Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Dancing Through Sunday Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Girl's Not Grey Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Death of Seasons Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Great Disappointment Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Paper Airplanes (Makeshift Wings) Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. This Celluloid Dream Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. But Home is Nowhere Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Hurricane Of Pain Unknown A.L.F. The Weakness Of The Inn Unknown A.L.F. I In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The World Beyond In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Acolytes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Thousand Suns In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Into The Ashes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Smoke and Mirrors In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Semblance Of Life In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Empyrean:Into The Cold Wastes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Floods In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The Departure In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams From A Buried Heart Legend Abigail Williams Like Carrion Birds Legend Abigail Williams The Conqueror Wyrm Legend Abigail Williams Watchtower Legend Abigail Williams Procession Of The Aeons Legend Abigail Williams Evolution Of The Elohim Unknown Abigail Williams Forced Ingestion Of Binding Chemicals Unknown Abigail -

Inte Bara Bögarnas Fest” En Queer Kulturstudie Av Melodifestivalen

”Inte bara bögarnas fest” En queer kulturstudie av Melodifestivalen Institutionen för etnologi, religionshistoria och genusvetenskap Examensarbete 30 HP Mastersprogrammet i genusvetenskap 120 HP Vårterminen 2018 Författare: Olle Jilkén Handledare: Kalle Berggren Abstract Uppsatsen undersöker hur TV-programmet Melodifestivalen förhåller sig till sin homokulturella status genom att studera programmets heteronormativa ramar och porträttering av queerhet. Det teoretiska ramverket grundar sig i representationsteori, kulturstudier, gaystudier och queerteori. Analysen resulterar i att de heteronormativa ramarna framställer heterosexualitet som en given norm i programmet. Detta uppvisas bland annat av en implicit heterosexuell manlig blick som sexualiserar kvinnokroppar och ser avklädda män, queerhet och femininitet som något komiskt. Detta komplicerar tidigare studiers bild av melodifestivaler som huvudsakligen investerade och accepterande av queera subjekt. Den queera representationen består främst av homosexuella män. Den homosexuellt manliga identiteten görs inte enhetlig och bryter mot heteronormativa ideal i olika grad. Några sätt som den homosexuellt manliga identiteten porträtteras är artificiell, feminin, icke-monogam, barnslig och investerad i schlager. Analysen påpekar att programmet har queert innehåll trots dess kommersiella framställning och normativa ideal. Nyckelord: Melodifestivalen, schlager, genusvetenskap, homokultur, gaystudier, bögkultur, heteronormativitet. Innehållsförteckning 1. En älskad och hatad ”homofilfestival” 1 -

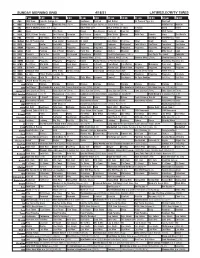

Sunday Morning Grid 4/18/21 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/18/21 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News SunPower Dest LA Bull Riding 25 Years of Tiger (N) PGA Golf 4 NBC Today in LA Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å Hockey Washington Capitals at Boston Bruins. (N) IndyCar Pre IndyCar 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch David Relief 7 ABC News This Week Ocean Sea Rescue Hearts of Free Ent. QB21 MLS Soccer 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Harvest Gold Coin Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX PROTECT Jack Hibbs Fox News Sunday The Issue PBA Bowling Super Slam. (N) RaceDay NASCAR Cup Series 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Jack Hibbs Paid Prog. Silver Shark News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Relief Dental SmileMO AAA Relief PROTECT Kenmore Bathroom? Paint Like A Can’tHear Transform Sex Abuse 2 2 KWHY Programa Programa Revitaliza Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Nick Lidia Milk Street Cook 2 8 KCET Darwin’s Cat in the SciGirls Odd Squad Cyberchase Biz Kid$ Great Performances (TVG) Å Easy Yoga: The Secret Colorado 3 0 ION Law & Order (TV14) Law & Order (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 3 4 KMEX Conexión Programa Programa Programa Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN R. -

Music in the Northern Woods: an Archaeological Exploration of Musical Instrument Remains

Michigan Technological University Digital Commons @ Michigan Tech Dissertations, Master's Theses and Master's Reports 2018 Music in the Northern Woods: An Archaeological Exploration of Musical Instrument Remains Matthew Durocher Michigan Technological University, [email protected] Copyright 2018 Matthew Durocher Recommended Citation Durocher, Matthew, "Music in the Northern Woods: An Archaeological Exploration of Musical Instrument Remains", Open Access Master's Thesis, Michigan Technological University, 2018. https://doi.org/10.37099/mtu.dc.etdr/575 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/etdr Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Musicology Commons MUSIC IN THE NORTHERN WOODS: AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPLORATION OF MUSICAL INSTRUMENT REMAINS By Matthew J Durocher A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE In Industrial Archaeology MICHIGAN TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Matthew J Durocher This thesis has been approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Industrial Archaeology. Department of Social Sciences Thesis Advisor: Dr. LouAnn Wurst Committee Member: Dr. Steven A. Walton Committee Member: M. Bartley Seigel Department Chair: Dr. Hugh Gorman Table of Contents List of Figures………………………………………………………………………….v List of Tables…………………………………………………………………………vii Acknowledgments........................................................................viii Abstract………………………………………………………………………………….x 1. There was music…………………………………………………………………..1 1.1. Enter Coalwood…………………………………………………………………………….3 1.2. A prelude……………………………………………………………………………………..7 2. Fresh Water, Ore, and Lumber……………………………………………10 2.1. Early logging and music in the Upper Peninsula………………………….…14 2.2. Cleveland Cliffs Iron Mining Company………………………………………….16 2.3. Coalwood: 1901-1912…………………………………………………………………..18 2.4. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………26 3. The Sounds of a Place.………………………………………………………..28 3.1. -

28 on the Road

ONON THETHE ROADROAD Journal of the Anabaptist Association of Australia and New Zealand Inc. No.28 SEPTEMBER 2005 CONTENTS 14 Mere Discipleship 1 THE VIEW FROM EPHESIANS FOUR 14 Overcoming ‘Unease Isolation’ 2 Walking In The Resurrection 15 Spirituality as Discipleship 6 It’s back to the future for the church 17 Herald Press Releases 9 The Mad Farmer 17 I am more used to seeing bullets 10 Whom Shall We Fear 18 Passing on the Comfort 11 Peace is the Way to Peace 18 Blessed Are the Peacemakers 12 BOOKS AND RESOURCES 19 Safe Passages On City Streets 12 Colossians Remixed: Subverting the Empire 19 AROUND THE WORLD 13 Manifesto: The Mad Farmer Liberation Front 19 MCC closes its programme in the Philippines THE VIEW FROM EPHESIANS FOUR MARK AND MARY HURST ...to prepare all God’s people for the work of Christian service What does mission look like in 21st century public officer. We take pleasure in sharing her passion for Australia? This is the question a conference called “Re- mission through home churches. imagining God and Mission Within Australian Cultures” Mark is presenting a paper called “Walking in the (http://www.missionstudies.org/au/ ) will tackle in Resurrection: An Anabaptist Approach to Mission in Melbourne 26-30 September. This Australian Missiology Australia.” Faithful readers of ON THE ROAD will Conference is taking place at Whitley College and will have recognize themes (and even snippets of articles) that have a few Kiwi voices represented too. Ross Langmead, appeared in these pages over the past ten years. This Professor of Missiology at Whitley College and Director of paper gave Mark the opportunity to pull these themes the School of World Mission and an AAANZ member is the together for a new audience.