LV March 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

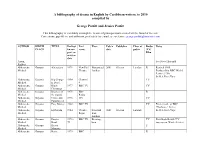

A Bibliography of Drama in English by Caribbean Writers, to 2010 Compiled By

A bibliography of drama in English by Caribbean writers, to 2010 compiled by George Parfitt and Jessica Parfitt This bibliography is inevitably incomplete. A note of principal sources used will be found at the end. Corrections, gap-fillers, and additions, preferably by e-mail, are welcome: [email protected] AUTHOR BIRTH TITLE Earliest Perf Place Pub’n Publisher Place of Radio Notes PLACE known venue date pub’n /TV/ perf. or Film written date Aaron, See Steve Hyacinth Philbert Abbensetts, Guyana Alterations 1978 New End Hampstead 2001 Oberon London R Revised 1985. Michael Theatre London Produced for BBC World Service 1980. In M.A.Four Plays Abbensetts, Guyana Big George 1994 Channel TV Michael Is Dead 4 Abbensetts, Guyana Black 1977 BBC TV TV Michael Christmas Abbensetts, Guyana Brothers of 1978 BBC R Michael the Sword Radio Abbensetts, Guyana Crime and 1976 ITV TV Michael Punishment Abbensetts, Guyana Easy Money 1982 BBC TV TV First episode of BBC Michael ‘Playhouse’ Series Abbensetts, Guyana El Dorado 1984 Theatre Stratford 2001 Oberon London In M.A.Four Plays Michael Royal East, London Abbensetts, Guyana Empire 1978 - BBC TV Birming- TV First black British T.V. Michael Road 79 ham soap opera. Wrote 2 series Abbensetts, Guyana Heavy F Michael Manners Abbensetts, Guyana Home 1975 BBC R Michael Again Radio Abbensetts, Guyana In The 1981 Hamp- London 2001 Oberon London In M.A.Four Plays Michael Mood stead Theatre Abbensetts, Guyana Inner City 1975 Granada Manchest- TV Episode One of ‘Crown Michael Blues TV er Court’ Abbensetts, Guyana Little 1994 Channel TV 4-part drama Michael Napoleons 4 Abbensetts, Guyana Outlaw 1983 Arts Leicester Michael Theatre Abbensetts, Guyana Roadrunner 1977 ITV TV First episode of ‘ITV Michael Playhouse’ series Abbensetts, Guyana Royston’s 1978 BBC TV Birming- 1988 Heinemann London TV Episode 4, Series 1 of Michael Day ham Empire Road. -

PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN a Publication of the Botanical Society of America, Inc

PLANT SCIENCE BULLETIN A Publication of the Botanical Society of America, Inc. Plant ldioblasts: Remarkable Examplesof Cell Specialization ADRIANCEs. FOSTER University of California (~~TE: Th!s paper,slightly a,bbreviat~d,is the ad~ress.of the chyma tissues, the remarkable cystolith-containing cells retiring president of the Botan,lcal SOCIety of. A?,enca gIVen ~t of the epidermis of Fiscus and Urtic d th ft - the annual banquet of the SOCIety, held at MIChIgan State Um- .,. a an e 0 en gro versity on September8, 1955. Dr. Foster'saddress was illus- tesque ramIfied sclerelds found In the leaves of many trated with a seriesof excellentslides of mixed botanicaland plants. Unicellular trichomes are epidermal idioblasts psycho-entomologicalnature.) and the guard cells of stomata might be regarded from One of the privileges-and certainly one of the pen- ~~ ontogenetic point of view as "paired" or "twin" alties--of having 'served as President of the Botanical IdlOblasts. Society is the delivery of a retiring addressat the culmi- My own interest in this motley assemblageof idio- nation of our annual meeting. In your present well-fed blastic cells arose during my early years as a teacher of and relaxed state, some of you may be resigned to listen- plant anatomy. It seemedto me then-as it does now ing to a historical and soporific resume of some special- -that any decision as to the suitable criteria to be used ized area of modern botanical research. A number of in classifying and discussing cell types and tissues in you perhaps may anticipate-probably with dismay- plants must consider the disturbing frequency of oc- a much broader non-technical type of discourse in- currence of idioblasts. -

GSBS News, Summer 2009

GSBS NEWS Summer 2009 Coming Soon... Two Specialized Masters Programs— TABLE OF CONTENTS Evoluti on, Progress, and Philanthropy 2 SPECIALIZED MASTERS PROGRAMS Geneti c Counseling Celebrates 20th Anniversary A celebrati on will be held October 3, 2009 marking the 20th anniversary of the start 3 DEAN’S NOTES of the UT Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences Geneti c Counseling Program. Founded by Jacqueline T. Hecht, Ph.D., and medical director Hope Northrup, M.D., 4 COMMENCEMENT ADDRESS (both are GSBS faculty at UT-Medical School)—the program is rich in its collabora- MICHAEL J. ZIGMOND, PH.D. ti ve structure with faculty at several Health Science Center Schools, M. D. Anderson Cancer Center and Baylor College of Medicine. The initi al graduati ng class in 1991 COMMENCEMENT PHOTOS included a single person. Today the Program, lead by Director, Claire Singletary, 6 MS, graduates 6 annually; it is the only accredited program of its kind in the state of Texas and only one of 31 in the country. Its dedicated purpose is to train health 8 COMMENCEMENT care professionals who provide supporti ve and educati onal counseling to families with geneti c condi- GREETINGS ti ons, birth defects, and geneti c predishpositi ons such as Achondroplasia, Down syndrome, cleft lip GIGI LOZANO, PH.D. and palate, spina bifi da, and hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. FACULTY PRESIDENT Geneti c Counseling graduate students do not receive tuiti on or sti pend support because it is a ter- minal Masters degree program; however, winning a competi ti ve scholarship provides a modest sum 9 GRADUATING CLASS and triggers in-state rather than out-of-state tuiti on for the student (about four ti mes as much). -

Azadi: a Freedom with Scar Dr

Volume II, Issue V, September 2014 - ISSN 2321-7065 Azadi: A Freedom with Scar Dr. Anand Kumar Lecturer in English at Mauri (Bhiwani) Abstract The partition of India was one of the most critical events in the history of world. It was a significance event that had far-reaching political, social, cultural, religious and psychological impacts on Indian as well as the Pakistan common mass. The historical process of partition had a profound impact on contemporary social culture, literature and history. This historical event of partition left a traumatic impression on the minds of the people. Even the effect of the partition can be seen at presenting in various types. Introduction Indian novel in English emerged in its full swing from last seven decades. The three prominent writers and old masters of Indian fiction English are Mulk Raj Anand, R.K. Narayan and Raja Rao contributed to enrich the Indian writing in English through their exclusive writing of short stories and novels. These pre-Independent Indian novelists have made use of history, social, cultural and political events in their writing. The second generation writers include Bhabani Bhattachary, Kamala Markandaya, Manohar Malgonkar, Khushwant Singh, Chaman Nahal Singh, Bhisam Sahni and many others also tried to capture Indian reality of partition in their own way and have narrated historical events truthfully in their Indian perspective. http://www.ijellh.com 434 Volume II, Issue V, September 2014 - ISSN 2321-7065 Chaman Nahal is one of the brilliant Indian English authors in the field of contemporary Indian English novels. He enriched the field of political fiction which is very poor as compared to other forms of Indian English fiction. -

Introduction the Age of Biology

INTRODUCTION THE AGE OF BIOLOGY An organism is the product of its genetic constitution and its en- vironment . no matter how uniform plants are genotypically, they cannot be phenotypically uniform or reproducible, unless they have developed under strictly uniform conditions. — Frits Went, 1957 A LITERARY and cinematic sensation, Andy Weir’s The Martian is engi- neering erotica. The novel thrills with minute technical details of com- munications, rocket fuel, transplanetary orbital calculations, and botany. The action concerns a lone astronaut left on Mars struggling to survive for 1,425 days using only the materials that equipped a 6-person, 30-day mission. Food is an early crisis: the astronaut has only 400 days of meals plus 12 whole potatoes. Combining his expertise in botany and engineer- ing, the astronaut first works to create in his Mars habitat the perfect Earth conditions for his particular potatoes, namely, a temperature of 25.5°C, plenty of light, and 250 liters of water. Consequently, his potatoes grow at a predicted rate to maturity in 40 days, thus successfully conjur- ing sufficient food to last until his ultimate rescue at the end of the novel. Unlike so many of the technical details deployed throughout the novel, the ideal conditions for growing potatoes are just a factoid. Whereas readers of the novel get to discover how to make water in a process oc- cupying twenty pages, the discovery of the ideal growing conditions of the particular potatoes brought to Mars is given one line.1 Undoubtedly, making water from rocket fuel is tough, but getting a potato’s maximum 3 © 2017 University of Pittsburgh Press. -

Toxic Consciousness in Indra Sinha's Animal's People

==================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 18:5 May 2018 India’s Higher Education Authority UGC Approved List of Journals Serial Number 49042 ==================================================================== Toxic Consciousness in Indra Sinha’s Animal’s People: An Ecocritical Study T. Geetha, Ph.D. Scholar & Dr. K. Maheshwari Abstract Literary writers, now-a-days, have penned down the destruction of nature and environment in all the genres of literature. The main objectives of the ecocritical writers are to provide awareness towards the end of peaceful nature. They particularly point out the polluted environment that leads to the execution of living beings in future. Indra Sinha is such the ecocritical writer who highlights the Bhopal gas tragedy and inhumanities of corporate companies, in his novel, Animal’s People. The environmental injustice that took place in the novel, clearly resembles the Bhopal Gas Tragedy that happened in 1984. The present study exhibits the consciousness of the toxic gas and its consequences to the innocent people in the novel. Keywords: Ecocriticism, Toxic Consciousness, Environmental Injustice, Bhopal gas tragedy and Corporate Inhumanities. Indra Sinha ==================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 18:5 May 2018 T. Geetha, Ph.D. Scholar & Dr. K. Maheshwari Toxic Consciousness in Indra Sinha’s Animal’s People: An Ecocritical Study 110 Indra Sinha, born in 1950, is the writer of English and Indian descent. His novel Animal People was published in 2009 that commemorated 25 years of the Bhopal Gas Tragedy. It recalled the world’s worst industrial disaster that took place in Indian city of Bhopal. On a December night in 1984, the ‘Union Carbide India Limited’ (UCIL), the part of US based multinational company, pesticide plant in Bhopal leaked around 27 tons of poisonous Methyl isocyanate gas, instantly killed thousands of people. -

The Trajectory of Feminist Ideals

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN (P): 2347–4564; ISSN (E): 2321–8878 Vol. 9, Issue 1, Jan 2021, 57–68 © Impact Journals THE TRAJECTORY OF FEMINIST IDEALS Aasha N P Research Scholar, Bharathiar University, Coimbatore, India Received: 31 Dec 2020 Accepted: 07 Jan 2021 Published: 30 Jan 2021 ABSTRACT Many feminist theories originated in the West and therefore reflected the social and cultural background of the writers and the nature of social configurations within which they sought explanations. More relevant for us are the family—immediate and extended—with its hold over loyalties of its members, a deeply hierarchic society stratified by caste and class, and persistent conflicts over religion, language, ethnicity and other differences. Studied here are two novels, both translated from Malayalam-one 4“Fire, Mv Witness” called ‘Agnisakshi in Malayalam, written by Lalithambika Antharjanam, and ‘The Scent of the Other Side’ called Othappu’ in Malayalam, written by Sarah Joseph. The first one was published in 1975 and the second one in 2005. This paper traces the trajectory of feminist ideals over the span of 35 years and concludes that women have always tried to grapple with the question of women’s subjectivity and agency. They have been victims of patriarchal systems and are partial collaborators. Women sometimes wear the marks of their subordination and their inferiority with pride. Devaki in Fire, My Witness and Margalitha in The Scent of the Other Side are the two characters studied to work out a conclusion. The Indian woman has indeed achieved success in half a century of independence, but if there is to be a truly female empowerment, much remains to be done. -

St. Joseph's College for Women, Tirupur, Tamilnadu

==================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 18:10 October 2018 India’s Higher Education Authority UGC Approved List of Journals Serial Number 49042 ==================================================================== St. Joseph’s College for Women, Tirupur, Tamilnadu R. Rajalakshmi, Editor Select Papers from the Conference Reading the Nation – The Global Perspective • Greetings from the Principal ... Rev. Sr. Dr. Kulandai Therese. A i • Editor's Preface ... R. Rajalakshmi, Assistant Professor and Head Department of English ii • Caste and Nation in Indian Society ... CH. Chandra Mouli & B. Sridhar Kumar 1-16 =============================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 18:10 October 2018 R. Rajalakshmi, Editor: Reading the Nation – The Global Perspective • Nationalism and the Postcolonial Literatures ... Dr. K. Prabha 17-21 • A Study of Men-Women Relationship in the Selected Novels of Toni Morrison ... G. Giriya, M.A., B.Ed., M.Phil., Ph.D. Research Scholar & Dr. M. Krishnaraj 22-27 • Historicism and Animalism – Elements of Convergence in George Orwell’s Animal Farm ... Ms. Veena SP 28-34 • Expatriate Immigrants’ Quandary in the Oeuvres of Bharati Mukherjee ... V. Jagadeeswari, Assistant Professor of English 35-41 • Post-Colonial Reflections in Peter Carey’s Journey of a Lifetime ... Meera S. Menon II B.A. English Language & Literature 42-45 • Retrieval of the Mythical and Dalit Imagination in Cho Dharman’s Koogai: The Owl ... R. Murugesan Ph.D. Research Scholar 46-50 • Racism in Nadine Gordimer’s The House Gun ... Mrs. M. Nathiya Assistant Professor 51-55 • Mysteries Around the Sanctum with Special Reference To The Man From Chinnamasta by Indira Goswami ... Mrs. T. Vanitha, M.A., M.Ed., M.Phil., Ph.D. -

An Ecological Human Bond with Nature in Indra Sinha's Animal's

International Journal of Engineering Trends and Applications (IJETA) – Volume 2 Issue 3, May-Jun 2015 RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS An Ecological Human Bond With Nature In Indra Sinha’s Animal’s People Ms. D.Aswini [1], Dr.S. Thirunavukkarasu [2] Research Scholar [1], Assistant Professor [2] MuthurangamGovt Arts College Otteri, Vellore Tamil Nadu - India ABSTRACT This paper explores the thematic desire to establish an ecological human bond with nature inIndraSinha’sAnimal’s People. Nature and literature have always shared a close relationship. India is a country with variety of ecosystems which ranges from Himalayas in the North to plateaus of South and from the dynamic Sunderbans in the East to dry Thar of the West. However our ecosystems have been affected due to increase in population and avarice of mankind in conquering more lands. As Environment and Literature are entwined, it is the duty of everyone to protect nature through words. Ecocriticism takes an earth centered approach to literary criticism. Although there are not many, there are few novels that can be read through the lens of ecocriticism. Keywords:- Chozhan, gurukulas I. INTRODUCTION literature and epics. Nature has been intimately In the same way,IndraSinha has riveted in connected with life in Indian tradition. Mountains, unveiling the concept of ecology in his novel. In particularly Himalayas are said to be the abode of God. Animal’s People, IndraSinha brings to limelight, the Rivers are considered and worshipped as goddesses, corporate crime of Bhopal gas attack in 1984. He has especially the holiest of holy rivers Ganga is a source done a rigorous research in their specific area of of salvation for anyone. -

The Matua Religious Movement of the 19 and 20

A DOWNTRODDEN SECT AND URGE FOR HUMAN DEVELOPMENT: THE MATUA RELIGIOUS MOVEMENT OF THE 19th AND 20th CENTURY BENGAL, INDIA Manosanta Biswas Santipur College, Kalyani University, Nadia , West Bengal India [email protected] Keywords : Bengal, Caste, Namasudra, Matua Introduction: Anthropologists and Social historians have considered the caste system to be the most unique feature of Indian social organization. The Hindu religious scriptures like Vedas, Puranas, and Smritishatras have recognized caste system which is nonetheless an unequal institution. As per purush hymn, depicted in Rig Veda, the almighty God, the creator of the universe, the Brahma,createdBrahmin from His mouth, Khastriya(the warrior class) from His two hands, Vaishya (the trader class) from His thigh and He created Sudra from His legs.1Among the caste divided Hindus, the Brahmins enjoyed the upper strata of the society and they were entitled to be the religious preacher and teacher of Veda, the Khastriyas were entrusted to govern the state and were apt in the art of warfare, the Vaishyas were mainly in the profession of trading and also in the medical profession, the sudras were at the bottom among the four classes and they were destined to be the servant of the other three classes viz the Brahmins, Khastriya and the Vaishya. The Brahmin priest used to preside over the social and religious festivities of the three classes except that of the Sudras. On the later Vedic period (1000-600 B.C) due to strict imposition of the caste system and intra-caste marriage, the position of different castes became almost hereditary.Marriages made according to the rules of the scriptures were called ‘Anulom Vivaha’ and those held against the intervention of the scriptures were called ‘Pratilom Vivaha’. -

Common Perspectives in Post-Colonial Indian and African Fiction in English

COMMON PERSPECTIVES IN POST-COLONIAL INDIAN AND AFRICAN FICTION IN ENGLISH ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Bottor of IN ENGLISH LITERATURE BY AMINA KISHORE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH ALIGARH MUSLIIVI UNIVERSITY ALIGARH 1995 Abstract The introduction of the special paper on Commonwealth Literature at the Post Graduate level and the paper called 'Novel other than British and American' at the Under Graduate level at AMU were the two major eventualities which led to this study. In the paper offered to the M A students, the grouping together of Literatures from atleast four of the Commonwealth nations into one paper was basically a makeshift arrangement. The objectives behind the formulation of such separate area as courses for special study remained vaguely described and therefore unjustified. The teacher and students, were both uncertain as to why and how to hold the disparate units together. The study emerges out of such immediate dilemma and it hopes to clarify certain problematic concerns related to the student of the Commonwealth Literature. Most Commonwealth criticism follows either (a) a justificatory approach; or (b) a confrontationist approach; In approach (a) usually a defensive stand is taken by local critics and a supportive non-critical, indulgent stand is adopted by the Western critic. In both cases, the issue of language use, nomenclature and the event cycle of colonial history are the routes by which the argument is moved. Approach (b) invariably adopts the Post-Colonial Discourse as its norm of presenting the argument. According to this approach, the commonness of Commonwealth Literatures emerges from the fact that all these Literatures have walked ••• through the fires of enslavement and therefore are anguished, embattled units of creative expression. -

Contemporary Women Novelists: a Feminist Study

CONTEMPORARY WOMEN NOVELISTS: A FEMINIST STUDY GITHA HARIHARAN, MANJU KAPUR AND ANITA NAIR A Thesis SUBMITTED TO THE TILAK MAHARASHTRA VIDYAPEETH PUNE FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In English Under the Board of Arts and Fine Arts studies BY Seema Ashok Bagul (Registration No.156130007736) UNDER THE GUIDANCE OF Dr.Madhavi Pawar DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Year - 2019 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled “Contemporary Women Novelists: A Feminist Study, Githa Hariharan, Manju Kapur and Anita Nair” completed and written by me has not previously been formed as the basis for the award of any Degree or other similar title upon me of this or any other Vidyapeeth or examining body. Place: Date: Signature of the Research Student CERTIFICATE OF THE SUPERVISOR It is certified that work entitled “Contemporary Women Novelists: A Feminist Study, Githa Hariharan, Manju Kapur and Anita Nair’’ is an original research work done by Smt. Seema Ashok Bagul under my supervision for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English to be awarded by Tilak Maharastra Vidyapeeth ,Pune. To best of my knowledge this thesis, Embodies the work of candidate Himself, herself has duly been completed Fulfills the requirement of the ordinance related to Ph.D. degree of TMV Up to the standard in respect of both content and language for being referred to the examiner. Signature of the supervisor ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS At the outset, I express my deep gratitude for my research guide, Dr.Madhavi Pawar, Karmaveer Hire College, Gargoti, Dist-Kolhapur, without whose scholarly guidance and deep insight I could never have completed my research work.