Waccasassa Bay Preserve State Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

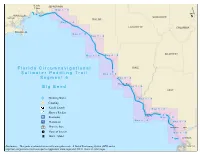

Florida Circumnavigational Saltwater Paddling Trail Segment 6 Big Bend

St. Marks JEFFERSON St. Marks MM aa pp 11 -- AA Sopchoppy WAKULLA Sopchoppy SUWANNEE TAYLOR MM aa pp 22 -- AA LAFAYETTE COLUMBIA FRANKLIN Lanark Village MM aa pp 22 -- BB MM aa pp 33 -- AA Dog Island GILCHRIST MM aa pp 33 -- BB MM aa pp 44 -- AA FF ll oo rr ii dd aa CC ii rr cc uu mm nn aa vv ii gg aa tt ii oo nn aa ll DIXIE SS aa ll tt ww aa tt ee rr PP aa dd dd ll ii nn gg TT rr aa ii ll MM aa pp 44 -- BB SS ee gg mm ee nn tt 66 MM aa pp 55 -- AA Horseshoe Beach BB ii gg BB ee nn dd MM aa pp 55 -- BB LEVY Drinking Water MM aa pp 66 -- AA Camping Kayak Launch MM aa pp 77 -- AA Shower Facility Cedar Key Restroom MM aa pp 77 -- BB MM aa pp 66 -- BB Restaurant MM aa pp 88 -- AA Grocery Store Yankeetown Inglis Point of Interest MM aa pp 88 -- BB Hotel / Motel CITRUS Disclaimer: This guide is intended as an aid to navigation only. A Gobal Positioning System (GPS) unit is Crystal River required, and persons are encouraged to supplement these maps with NOAA charts or other maps. Segment6: Big Bend Map 1 - A US 98 Aucilla Launch N: 30.1165 I W: -83.9795 A Aucilla Launch E C O St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge N F Gator Creek I N 3 A 3 R I Oyster Creek V E R 3 Cow Creek R 3 D 3 Black Rock Creek 3 Sulfur Creek Pinhook River Grooms Creek 3 Snipe Island Unit Pinhook River Entrance N: 30.0996 I W: -84.0157 Aucilla River 6 Cabell Point 3 Cobb Rocks Gamble Point 3 Gamble Point 6 Sand Creek Econfina Primitive Campsite N: 30.0771 I W: -83.9892 B Econfina River State Park Big Bend Seagrasses Aquatic Preserve Rose Creek 6 12 Econfina Landing A N: 30.1166 -

Segment 6 Map Book

St. Marks JEFFERSON St. Marks MM aa pp 11 -- AA Sopchoppy WAKULLA Sopchoppy SUWANNEE TAYLOR MM aa pp 22 -- AA LAFAYETTE COLUMBIA FRANKLIN Lanark Village MM aa pp 22 -- BB MM aa pp 33 -- AA Dog Island GILCHRIST MM aa pp 33 -- BB MM aa pp 44 -- AA DIXIE FF ll oo rr ii dd aa CC ii rr cc uu mm nn aa vv ii gg aa tt ii oo nn aa ll SS aa ll tt ww aa tt ee rr PP aa dd dd ll ii nn gg TT rr aa ii ll MM aa pp 44 -- BB SS ee gg mm ee nn tt 66 MM aa pp 55 -- AA Horseshoe Beach BB ii gg BB ee nn dd MM aa pp 55 -- BB LEVY Drinking Water MM aa pp 66 -- AA Camping Kayak Launch MM aa pp 77 -- AA Shower Facility Cedar Key Restroom MM aa pp 77 -- BB MM aa pp 66 -- BB Restaurant MM aa pp 88 -- AA Grocery Store Yankeetown Inglis Point of Interest MM aa pp 88 -- BB Hotel / Motel CITRUS Disclaimer: This guide is intended as an aid to navigation only. A Gobal Positioning System (GPS) unit is Crystal River required, and persons are encouraged to supplement these maps with NOAA charts or other maps. Segment6: Big Bend Map 1 - A US 98 Aucilla Launch N: 30.1165 I W: -83.9795 A Aucilla Launch ECONFINA RIVER RD St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge Gator Creek 3 3 Oyster Creek Cow Creek 3 3 3 Black Rock Creek 3 Sulfur Creek Pinhook River Grooms Creek 3 Snipe Island Unit Pinhook River Entrance N: 30.0996 I W: -84.0157 Aucilla River 6 Cabell Point 3 Cobb Rocks Gamble Point 3 Gamble Point 6 Sand Creek Econfina Primitive Campsite N: 30.0771 I W: -83.9892 B Econfina River State Park Big Bend Seagrasses Aquatic Preserve Rose Creek 6 12 Econfina Landing A N: 30.1166 | W: -83.9796 -

Kings Bay/Crystal River Springs Restoration Plan

Kings Bay/Crystal River Springs Restoration Plan Kings Bay/Crystal River Springs Restoration Plan Kings Bay/Crystal River Springs Restoration Plan Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................. 1 Section 1.0 Regional Perspective ............................................................ 1 1.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Why Springs are Important ...................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Springs Coast Springs Focus Area ........................................................................................... 2 1.4 Description of the Springs Coast Area .................................................................................... 3 1.5 Climate ......................................................................................................................................... 3 1.6 Physiographic Regions .............................................................................................................. 5 1.7 Karst ............................................................................................................................................. 5 1.8 Hydrogeologic Framework ...................................................................................................... 7 1.9 Descriptions of Selected Spring Groups ................................................................................ -

The Red-Cockaded Woodpecker: a Selectively Annotated Bibliography

UCLA Electronic Green Journal Title The Red-Cockaded Woodpecker: A Selectively Annotated Bibliography Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6013d8ks Journal Electronic Green Journal, 1(8) Author Wishard, Lisa Publication Date 1998 DOI 10.5070/G31810297 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Red-Cockaded Woodpecker: A Selectively Annotated Bibliography Lisa A. Wishard The Pennsylvania State University ..................................... I. Introduction The red-cockaded woodpecker was first identified by Louis Jean Pierre Viellot in 1807 as Picoides borealis or northern woodpecker. Viellot wrongly assumed that this southern species ranged into the northern United States and Canada. In the 1880's Alexander Wilson became the first to apply to the species the common name, red-cockaded woodpecker. This gregarious woodpecker once common in the longleaf pine forests of the southeastern United States has been on the endangered species list since October 1970 (under a law that proceeded the Endangered Species Act of 1973). The red-cockaded woodpecker is cardinal-sized, measuring approximately seven inches long with a fifteen-inch wingspan. The males of the species wear a black cap, with a red streak worn like a cockade on either side. This streak is the species rarely visible but distinguishing mark and namesake. Both the male and the female of the species have a distinctive black nape which encircles large white patches on the cheek along with black and white horizontal bars on the back. The young of the species bear the same general colors and patterns of the adults, but young males will have an oval shaped patch of crimson on their crown. -

Pine Island Ridge Management Plan

Pine Island Ridge Conservation Management Plan Broward County Parks and Recreation May 2020 Update of 1999 Management Plan Table of Contents A. General Information ..............................................................................................................3 B. Natural and Cultural Resources ...........................................................................................8 C. Use of the Property ..............................................................................................................13 D. Management Activities ........................................................................................................18 E. Works Cited ..........................................................................................................................29 List of Tables Table 1. Management Goals…………………………………………………………………21 Table 2. Estimated Costs……………………………………………………………….........27 List of Attachments Appendix A. Pine Island Ridge Lease 4005……………………………………………... A-1 Appendix B. Property Deeds………….............................................................................. B-1 Appendix C. Pine Island Ridge Improvements………………………………………….. C-1 Appendix D. Conservation Lands within 10 miles of Pine Island Ridge Park………….. D-1 Appendix E. 1948 Aerial Photograph……………………………………………………. E-1 Appendix F. Development Agreement………………………………………………….. F-1 Appendix G. Plant Species Observed at Pine Island Ridge……………………………… G-1 Appendix H. Wildlife Species Observed at Pine Island Ridge ……... …………………. H-1 Appendix -

Plant Species List for Bob Janes Preserve

Plant Species List for Bob Janes Preserve Scientific and Common names obtained from Wunderlin 2013 Scientific Name Common Name Status EPPC FDA IRC FNAI Family: Azollaceae (mosquito fern) Azolla caroliniana mosquito fern native R Family: Blechnaceae (mid-sorus fern) Blechnum serrulatum swamp fern native Woodwardia virginica Virginia chain fern native R Family: Dennstaedtiaceae (cuplet fern) Pteridium aquilinum braken fern native Family: Nephrolepidaceae (sword fern) Nephrolepis cordifolia tuberous sword fern exotic II Nephrolepis exaltata wild Boston fern native Family: Ophioglossaceae (adder's-tongue) Ophioglossum palmatum hand fern native E I G4/S2 Family: Osmundaceae (royal fern) Osmunda cinnamomea cinnamon fern native CE R Osmunda regalis royal fern native CE R Family: Polypodiaceae (polypody) Campyloneurum phyllitidis long strap fern native Phlebodium aureum golden polypody native Pleopeltis polypodioides resurrection fern native Family: Psilotaceae (whisk-fern) Psilotum nudum whisk-fern native Family: Pteridaceae (brake fern) Acrostichum danaeifolium giant leather fern native Pteris vittata China ladder break exotic II Family: Salviniaceae (floating fern) Salvinia minima water spangles exotic I Family: Schizaeaceae (curly-grass) Lygodium japonicum Japanese climbing fern exotic I Lygodium microphyllum small-leaf climbing fern exotic I Family: Thelypteridaceae (marsh fern) Thelypteris interrupta hottentot fern native Thelypteris kunthii widespread maiden fern native Thelypteris palustris var. pubescens marsh fern native R Family: Vittariaceae -

Attachment J: Thermal Imaging of the Waccasassa Bay Preserve

ATTACHMENT J Thermal Imaging of the Waccasassa Bay Preserve: Image Acquisition and Processing By Ellen A. Raabe and Elzbieta Bialkowska-Jelinska SUBMITTED BY DAN HILLIARD Prepared in cooperation with Waccasassa Bay Preserve State Park and Florida Springs Initiative Thermal Imaging of the Waccasassa Bay Preserve: Image Acquisition and Processing By Ellen A. Raabe and Elzbieta Bialkowska-Jelinska Open-File Report 2010–1120 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Prepared in cooperation with Waccasassa Bay Preserve State Park and Florida Springs Initiative Thermal Imaging of the Waccasassa Bay Preserve: Image Acquisition and Processing By Ellen A. Raabe and Elzbieta Bialkowska-Jelinska Open-File Report 2010–1120 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey ii U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia 2010 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Suggested citation: Raabe, E.A. and Bialkowska-Jelinska, E., 2010, Thermal Imaging of the Waccasassa Bay Preserve: image acquisition and processing: U.S. Geological Survey Open File Report 2010-1120, 69 p. Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted material contained within this report. -

Understory Plants on Reforested Pastures at Finca Alexis, Puntarenas, Costa Rica

Project report Understory plants on reforested pastures at Finca Alexis, Puntarenas, Costa Rica PP Tropenbotanik und Pflanzen-Tier-Interaktionen in Costa Rica by Angelika Till WS 19/20 Supervisor: Mag. Dr. Anton Weissenhofer Introduction Costa Rica, as one of the most biodiverse countries worldwide, accommodates about 9,361 plant species, including ferns and fern allies, Gymnosperms and Angiosperms (Hammel et al., 2004). There are several studies about plant biodiversity in the tropics, but since there is such an immense species richness, there is still a significant gap in the knowledge of several plant groups, e.g. understorey plants. Understory plants make up about half of the Costa Rican flora, consisting of herbs (27%), treelets (16%), and part of vines (16%) (Hammel et al., 2004). Nevertheless, most of the conducted studies are concerned with tree biodiversity (Gentry & Dodson, 1987a; Huber, 1996; Huber et al., 2008; Mayfield & Daily, 2005). This is why this survey pursues the study of understory plants in the Golfo Dulce region where the La Gamba Field Station is situated. A first survey on the herbaceous flora around La Gamba has been conducted by Holzer et al. (2016) during a field course of the University of Vienna in 2016. This study focuses on the understory flora of Finca AleXis. Finca AleXis is a former pasture with a farmhouse (Casa AleXis) of the Tropical station at the Fila Consteña mountain range (Fila Cal) that was converted into a simple field station. It is part of the COBIGA project (Corredor Biológico La Gamba) with the goal to form a rainforest corridor between the tropical mountain rainforest of Fila Cal and the lowland rainforest of the Golfo Dulce (https://www.regenwald.at/en/project-information/biological-corridor- cobiga-forest-and-climate-protection). -

Distrito Regional De Manejo Integrado Cuervos Plan De

DISTRITO REGIONAL DE MANEJO INTEGRADO CUERVOS PLAN DE MANEJO Convenio Marco 423-2016, Acta de ejecución CT-2016-001532-10 - Cornare No 564-2017 Suscrito entre Cornare y EPM “Continuidad del convenio interadministrativo 423-2016 acta de ejecución CT-2016-001532-10 suscrito entre Cornare y EPM para la implementación de proyectos de conservación ambiental y uso sostenible de los recursos naturales en el Oriente antioqueño” PRESENTADO POR: GRUPO BOSQUES Y BIODIVERSIDAD CORNARE EL Santuario – Antioquia 2018 REALIZACIÓN Corporación Autónoma Regional de las Cuencas de los Ríos Negro y Nare – Cornare GRUPO BOSQUES Y BIODIVERSIDAD COORDINADORA DE GRUPO BOSQUES Y BIODIVERSIDAD ELSA MARIA ACEVEDO CIFUENTES Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad SUPERVISOR DAVID ECHEVERRI LÓPEZ Biólogo (E), Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad SUPERVISOR EPM YULIE ANDREA JÍMENEZ GUZMAN Ingeniera Forestal, Epm EQUIPO PROFESIONAL GRUPO BOSQUES Y BIODIVERSIDAD LUZ ÁNGELA RIVERO HENAO Ingeniera Forestal, Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad EDUARDO ANTONIO RIOS PINEDO Ingeniero Forestal, Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad DANIEL MARTÍNEZ CASTAÑO Biólogo, Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad STIVEN BARRIENTOS GÓMEZ Ingeniero Ambiental, Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad NICOLAS RESTREPO ROMERO Ingeniero Ambiental, Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad JULIETH VELASQUEZ AGUDELO Ingeniera Forestal, Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad SANTIAGO OSORIO YEPES Ingeniero Forestal, Grupo Bosques y Biodiversidad TABLA DE CONTENIDO 1. INTRODUCCIÓN .......................................................................................................... -

Nature Coast State Trail Management Plan

APPENDIX B State Designation National Recreation Trail (NRT) Designation THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Appendix B-1 Appendix B-2 Appendix B-3 Appendix B-4 .Appendix A Designated State Parks Long Key 05 Monroe 763.24 147.95 Lease--- Trustees 09121/61 Pari< Open-Fee Required / /' State Pari< - Lower Wekiva River 03 Lake 17,137.55 588.02 Lease Trustees 08119176 Preserve Open-No Fee Required Preserve Stale Park Seminole' Madlra Bickel Mound 04" Manatee ., 5.68 4.32 Lease Trustees 04116148 Special Feature Site (A) Open-No Fee Required State Archaeological Site' Mike Roess Gold Head 02 Clay 2,059.67 115.47 lease Trustees 02115136 Park Open-Fee Required Branch State Pari< '''' ~ . '.' .''' . Mound Key ': • ,." . 04 lee 168.86 Lease Trustees 11/02161 Special Feature Site (A) Open-No Fee Required An:haeologicat State Pari< L',_ .... , Nature Coast Trail 02 Dixie 469.71 Lease: Trustees 12118196 Trail Open-No Fee Required State Park Gilchrist levy " '" .. ' North,Peninsula State Park 03 Volusla 519.90 "- 2.36 Lease Trustees 05116184 Recreation Area Open-No Fee Requ1ied alene 02 . A1achua .. ·__ . 1,714. 17 26.99 Lease Trustees 06129/36 ·.,Park Open-Fee Required State Park Columbia Ochlockonee River · .. 01 Wakulla. .'-370.33 15.13 Lease Trustees 05114170, Pari< Open-Fee Required State Park OletaRiver ._.,05 ..... Dade ... 1,012.64. 20.20 Lease Trustees 06109160 Recreation Ar.ea Open-Fee Required State Park Orman House ..... - ~ .. --,- 01 .. Franklin.' _'. " 1.SO Lease Trustees 02/02/01 Undetennined Open-Fee Requir~ Oscar Scherer 04 , 'Sarasota 1,376.96 4.66 Lease Trustees 09/12/56 Park Open-Fee Required State Park - .: ~ ;" Paynes Creek 04 Hardee 396.20 Lease Trustees 09/19n4 Special Feature Site (H) Open-Fee Required H"lStoric State Park ."."'(" .-.,--. -

The Rhexia Paynes Prairie Chapter Florida Native Plant Society April 2011

The Rhexia Paynes Prairie Chapter Florida Native Plant Society April 2011 Monthly Chapter VP’s Message Meeting and Field Trip Alachua County Forever; or Alachua County Forsaken? Information Joni Ellis “One of the penalties of an ecological education is and Mill Creek Preserve., two of the most that one lives alone in a world of wounds. Much of the significant wild lands in the county. Spring Native Plant Sale damage inflicted on land is quite invisible to laymen. An April 8, members only, ecologist must either harden his shell and make believe that the consequences of science are none of his busi- Mill Creek Preserve contains one of the south- 4:30 - 6:30 ness, or he must be the doctor who sees the marks of ernmost populations of American beech trees April 9, public , 8:30-12:30 death in a community that believes itself well and does in the U.S. Its outstanding biotic features include Morningside Nature not want to be told otherwise.” — Aldo Leopold magnificent examples of beech and magnolia Center slope forest, the largest area of pond pine flat- Some interesting things are brewing in the 3540 E University Ave woods remaining in Alachua County, as well as minds of those who can live without wild Gainesville, FL 32641 the largest population of the state-listed pond things. Some are actually calling for the sale of spice in the county. conservation land to balance their budgets. Alachua County voters overwhelmingly Barr Hammock is a 2300 acre “land bridge” Chapter Meeting, April agreed to tax themselves to purchase impor- that connects two of the largest wetlands in the 19, 2011: Erick Smith, tant conservation lands through the Alachua county - Ledwith Prairie and Levy Prairie. -

CARIBBEAN REGION - NWPL 2014 FINAL RATINGS User Notes: 1) Plant Species Not Listed Are Considered UPL for Wetland Delineation Purposes

CARIBBEAN REGION - NWPL 2014 FINAL RATINGS User Notes: 1) Plant species not listed are considered UPL for wetland delineation purposes. 2) A few UPL species are listed because they are rated FACU or wetter in at least one Corps region.