ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: SELECTED BASSOON

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orpheus Choir a Ministry in Music

Olivet Nazarene University Digital Commons @ Olivet School of Music: Performance Programs Music 2008 Department of Music Programs 2007 - 2008 Department of Music Olivet Nazarene University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/musi_prog Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Department of Music, "Department of Music Programs 2007 - 2008" (2008). School of Music: Performance Programs. 41. https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/musi_prog/41 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at Digital Commons @ Olivet. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music: Performance Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Olivet. For more information, please contact [email protected]. S o ’feiS Department of Music 2007 - 2008 Programs Calendar of Events FALL 2007 SEPTEMBER 2007 1 11 Voice Faculty Recital 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 <- Kresge Auditorium 4- 7 p.m. 13 Adjunct Faculty Recital: 9 10 Q 12 0 14 15 Jennifer Reddick 16 17 18 19 20 o ® <- Kresge Auditorium <r 7:30 p.m. 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 21-22 Broadway Revue 30 <- Kresge Auditorium <- 7 & 9 p.m. OCTOBER 2007 1 2 3 o 5 O 4 Orchestra and Chamber Concert <r Kresge Auditorium <- 7 p.m. 7 8 9 10 11 0 0 6 Marching Band Exhibition 15 16 17 18 © Watseka, III. <- 2 p.m. 21 22 23 24 25 26 ® 12-14 Orchestra Tour <r Various Churches © 29 30 31 19-20 Orpheus Variety Show <- Kresge Auditorium <- 7 & 9 p.m. -

An Analysis of Honegger's Cello Concerto

AN ANALYSIS OF HONEGGER’S CELLO CONCERTO (1929): A RETURN TO SIMPLICITY? Denika Lam Kleinmann, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2014 APPROVED: Eugene Osadchy, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor David Schwarz, Committee Member Daniel Arthurs, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the School of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kleinmann, Denika Lam. An Analysis of Honegger’s Cello Concerto (1929): A Return to Simplicity? Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2014, 58 pp., 3 tables, 28 examples, 33 references, 15 titles. Literature available on Honegger’s Cello Concerto suggests this concerto is often considered as a composition that resonates with Les Six traditions. While reflecting currents of Les Six, the Cello Concerto also features departures from Erik Satie’s and Jean Cocteau’s ideal for French composers to return to simplicity. Both characteristics of and departures from Les Six examined in this concerto include metric organization, thematic and rhythmic development, melodic wedge shapes, contrapuntal techniques, simplicity in orchestration, diatonicism, the use of humor, jazz influences, and other unique performance techniques. Copyright 2014 by Denika Lam Kleinmann ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………………..iv LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES………………………………………………………………..v CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION………..………………………………………………………...1 CHAPTER II: HONEGGER’S -

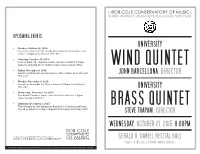

John Barcellona, Director University University

UPCOMING EVENTS UNIVERSITY • Monday, October 26, 2015: Guest Artist Recital, LSU Faculty Wind Quintet: Masterclass and Concert 8:00pm Daniel Recital Hall FREE • Thursday, October 29, 2015: Concert Band: Spooktacular, Jermie Arnold, conductor 7:00pm WIND QUINTET Daniel Recital Hall $10/7; children under 13 in costume FREE • Friday, November 6, 2015: Faculty Artist Recital, John Barcellona, flute 8:00pm Daniel Recital JOHN BARCELLONA, DIRECTOR Hall $10/7 • Monday, November 9, 2015: Saxophone Ensemble, Jay Mason, director 8:00pm Daniel Recital Hall $10/7 UNIVERSITY • Wednesday, November 18, 2015: Woodwind Chamber Music, John Barcellona, director 8:00pm Daniel Recital Hall $10/7 BRASS QUINTET • Thursday, December 3, 2015: Wind Symphony and Symphonic Band, John Carnahan and Jermie Arnold, conductors 8:00pm Carpenter Performing Arts Center $10/7 STEVE TRAPANI, DIRECTOR WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 21, 2015 8:00PM For tickets please call 562.985.7000 or visit the web at: GERALD R. DANIEL RECITAL HALL PLEASE SILENCE ALL ELECTRONIC MOBILE DEVICES. This concert is funded in part by the INSTRUCTIONALLY RELATED ACTIVITIES FUNDS (IRA) provided by California State University, Long Beach. PROGRAM Suite Cantabile for Woodwind Quintet .......................................Bill Douglas Sonatine .........................................................................................Eugene Bozza I. Bachianas Africanas (b. 1944) I Allegro vivo (1905-1991) II. Funk Ben Ritmico II Andante ma non troppo III. Intermezzo III Allegro vivo IV. Samba Cantando IV Largo - Allegro vivo Summer Music ............................................................................. Samuel Barber Quintet ........................................................................................ Michael Kamen (1910-1981) (1948-2003) UNIVERSITY WOODWIND QUINTET Suite Americana ........................................................................ Enrique Crespo Vanessa Fourla—flute, Spencer Klass—oboe 1. Ragtime (b. 1941) Nick Cotter—clarinet, Jennifer Ornelas—horn 3. Vals Peruano Emily Prather—bassoon 5. -

Alternative Strategies for the Refinement of Bassoon Technique Through the Concert Etudes, Op

Alternative Strategies for the Refinement of Bassoon Technique Through the Concert Etudes, Op. 26, by Ludwig Milde Item Type Electronic Dissertation; text Authors Zuniga Chanto, Fernando Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 09/10/2021 13:14:01 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/145124 ALTERNATIVE STRATEGIES FOR THE REFINEMENT OF BASSOON TECHNIQUE THROUGH THE CONCERT ETUDES, OP. 26, BY LUDWIG MILDE by Fernando Zúñiga Chanto ______________________________ Copyright © Fernando Zúñiga Chanto 2011 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2011 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Fernando Zúñiga Chanto entitled Alternative Strategies for the Refinement of Bassoon Technique Through The Concert Etudes, Op. 26, by Ludwig Milde and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Date: 4/18/2011 William Dietz Date: 4/18/2011 Jerry Kirkbride Date: 4/18/2011 Brian Luce Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this document prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement. -

SONGS DANCES Acknowledgments & Recorded at St

SONGS DANCES Acknowledgments & Recorded at St. Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church, Jacksonville, Florida on June 13 and 14, 2018 Jeff Alford, Recording Engineer Gary Hedden, Mastering Engineer in THE SAN MARCO CHAMBER MUSIC SOCIETY collaboration THE LAWSON ENSEMBLE with WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1753 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. BOX 137, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA8 0XD TEL: 01539 824008 © 2018 ALBANY RECORDS MADE IN THE USA DDD WARNING: COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS IN ALL RECORDINGS ISSUED UNDER THIS LABEL. SanMarco_1753_book.indd 1-2 10/18/18 9:36 AM The Music a flute descant – commences. Five further variations ensue, each alternating characters and moods: a brisk second variation; a slow, sad, waltzing third; a short, enigmatic fourth; a sprawling fifth, this the Morning Elation for oboe and viola by Piotr Szewczyk (2010) emotional heart of the composition; and a contrapuntal sixth, which ends with a restatement of the theme Piotr Szewczyk was fairly new to Jacksonville when I asked him if he could compose an oboe/viola duo for now involving the flute. us in 2010, so I did not expect the enthusiasm and speed in which he composed “Morning Elation”! Two In all, it’s a complex, ambitious score, a glowing example of the American Romantic style of which days later he greeted me with the news that he had a burst of inspiration and composed our piece the day Beach, along with George Whitefield Chadwick, John Knowles Paine, and Arthur Foote, was such a wonder- before. -

2015-2016 New Music Festival

Tenth Annual New Music Festival 4 events I 5 world premieres I 40 performers Ellen Taaffe Zwilich, Composer-in Residence Lisa Leonard, Director February 23 - February 26, 2016 2015-2016 Season SPOTLIGHT I: YOUNG COMPOSERS Tuesday, February 23 at 7:30 p.m. Matthew Hakkarainen Florida MTNA winner (b.2000) The Suite for Three Animals (2015) Hopping Hare Growling Bear Galloping Mare Matthew Hakkarainen, violin David Jonathan Rogers Piano Trio, Op.10 (2015) (b. 1990) Arcs Fractals Collage Yasa Poletaeva, violin; Elizabeth Lee, cello Darren Matias, piano Trevor Mansell Six Miniatures for Wind Trio (2014) (b. 1996) World Premiere Pastorale Nocturne March Minuet Aubade Rondo Cameron Hewes, clarinet; Trevor Mansell, oboe Michael Pittman, bassoon Alfredo Cabrera (b. 1996) from The Whistler Suite, Op. 5 (2015-16) Innocence World Premiere Sadness & Avarice Beauty & Anger Sheng-Yuan Kuan, piano Pause Chen Liang Two movements from String Quartet (2015-2016) (b. 1991) World Premiere Andante Rondo Junheng Chen & Yvonne Lee, violins Hao Chang, viola; Nikki Khabaz Vahed, cello Anthony Trujillo The Four Nocturnes (2015) (b. 1995) World Premiere Matthew Calderon, piano Matthew Carlton Septet (2015) (b. 1992) World Premiere John Weisberg, oboe; Cameron Hewes, bass clarinet Hugo Valverde, French horn; Michael Pittman, bassoon Yaroslava Poletaeva, violin; Darren Matias, piano Anastasiya Timofeeva, celesta MASTER CLASS with ELLEN TAAFFE ZWILICH Wednesday, February 24 at 7:30 p.m. Selections from the following compositions by Lynn student composers will be performed and discussed. Alfredo Cabrera (b. 1996) from The Whistler Suite, Op. 5 (2015-16) Innocence Sadness & Avarice Beauty & Anger Sheng-Yuan Kuan, piano Chen Liang Two movements from String Quartet (2015-2016) (b. -

Repertoire List

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

Wind Ensemble Repertoire

UNCG Wind Ensemble Programming April 29, 2009 Variations on "America" ‐ Charles Ives, arr. William Schuman and William Rhoads Symphonic Dances from West Side Story Leonard Bernstein, arr. Paul Lavender Mark Norman, guest conductor Children's March: "Over the Hills and Far Away” Percy Grainger Kiyoshi Carter, guest conductor American Guernica Adolphus Hailstork Andrea Brown, guest conductor Las Vegas Raga Machine Alejandro Rutty, World Premiere March from Symphonic Metamorphosis Paul Hindemith, arr. Keith Wilson March 27, 2009 at College Band Directors National Association National Conference, Bates Recital Hall, University of Texas at Austin Fireworks, Opus 8 Igor Stravinsky, trans. Mark Rogers It perched for Vespers nine Joel Puckett Theme and Variations, Opus 43a Arnold Schoenberg Shadow Dance David Dzubay Commissioned by UNCG Wind Ensemble Four Factories Carter Pann Commissioned by UNCG Wind Ensemble FuniculiFunicula Rhapsody Luigi Denza, arr. Yo Goto February 20, 2009 Fireworks, Op. 4 Igor Stravinsky, trans. Mark Rogers O Magnum Mysterium Morten Lauridsen H. Robert Reynolds, guest conductor Theme and Variations, Op. 43a ‐ Arnold Schoenberg Symphony No. 2 Frank Ticheli Frank Ticheli, guest conductor December 3, 2008 Raise the Roof ‐ Michael Daugherty John R. Beck, timpani soloist Intermezzo Monte Tubb Andrea Brown, guest conductor Shadow Dance David Dzubay Four Factories Carter Pann FuniculiFunicula Rhapsody Luigi Denza, arr. Yo Goto October 8, 2008 Fireworks, Opus 8 ‐ Igor Stravinsky, trans. Mark Rogers it perched for Vespers nine Joel Puckett Theme and Variations, Op. 43a Arnold Schoenberg Fantasia in G J.S. Bach, arr. R. F. Goldman Equus ‐ Eric Whitacre Andrea Brown, guest conductor Entry March of the Boyars Johan Halvorsen Fanfare Ritmico ‐ Jennifer Higdon May 4, 2008 Early Light Carolyn Bremer Icarus and Daedalus ‐ Keith Gates Emblems Aaron Copland Aegean Festival Overture Andreas Makris Mark A. -

Pacific 231 (Symphonic Movement No

Pacific 231 (Symphonic Movement No. 1) Arthur Honegger (1892–1955) Written: 1923 Movements: One Style: Contemporary Duration: Six minutes As a young man trying to figure his way in the world of music, Miklós Rózsa (a Hollywood film composer) asked the French composer Arthur Honegger “How are we composers expected to make a living?” “Film music,” he said. “What?” I asked incredulously. I was unable to believe that Arthur Honegger, the composer of King David, Judith and other great symphonic frescos, of symphonic poems and chamber music, could write music for films. I was thinking of the musicals I had seen in Germany and of films like The Blue Angel, so I asked him if he meant foxtrots and popular songs. He laughed again. “Nothing like that,” he said, ‘I write serious music.’ As a young man, Honegger was part of a group of renegade composers in Paris grouped around the avant-garde poet Jean Cocteau called “Les Six.” Unlike, the other composers in “Les Six,” Honegger’s music is weightier and less flippant. In the 1920s, Honegger worked on three short orchestral pieces that he called Mouvements symphonique. In his autobiography, I am a Composer, he recounts his intent with the first: To tell the truth, In Pacific I was on the trail of a very abstract and quite ideal concept, by giving the impression of a mathematical acceleration of rhythm, while the movement itself slowed. It was only after he wrote the work that he gave it the title. “A rather romantic idea crossed my mind, and when the work was finished, I wrote the title, Pacific 231, which indicates a locomotive for heavy loads and high speed.” Given a title, people heard things that weren’t there. -

Spring Recital Program

~PROGRAM~ 1. Sheep May Safely Graze……J.S. Bach/ Arr. Ricky Lombardo 2. Silver Celebration…………..……………..Catherine McMichael UIS Flute Choir 3. Six Studies in English Folk Song……………Vaughn Williams I. Adagio IV. Lento V. Andante tranquillo Angelina Einert, bass clarinet; Yiqing Zhu, piano 4. All of Me……………………………..John Legend and Toby Gad James Ukonu, Alexis Hogan Hobson, voices; Pamela Scott*, piano 5. String Quartet No.1…………………………Serge Rachmaninoff Romance Samantha Hwang, Natalie Kerr, violins; Savannah Brannan, viola; Kevin Loitz, cello 6. Cavatina………………………………………………John Williams 7. And I love Her…………………..John Lennon, Paul McCartney Josh Song*, guitar 8. Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso…...Camille Saint Saëns Meredith Crifasi, violin; Maryna Meshcherska, piano 9. Sweet Rain………………………………………………Bill Douglas 10. Return to Inishmore…………………………………Bill Douglas Kristin Sarvela*, oboe; Yichen Li*, piano 11. Five Hebrew Love Songs…………………………Eric Whitacre I. Temuná II. Kalá Kallá III. Lárov IV. Éyze shéleg V. Rakút Brooke Seacrist, voice and tambourine; Meredith Crifasi, violin; Yiqing Zhu, piano 12. Stereogram………………………………………….Dave Brubeck #3-For George Roberts #7-For Dave Taylor Bill Mitchell*, Bass Trombone 13. In Ireland………………………………………….Hamilton Harty Abigail Walsh*, flute; Pei-I Wang*, piano 14. Ahe Lau Makani………….Lili’uokalani, Likelike,and Kapoli; (There is a Breath) Arranged by Jerry Depuit 15. “Nachtigall, Sie Singt So Schӧn”………….Johannes Brahms Liebeslieder No. 15 Text by Georg Friedrich Daumer 16. Africa……………………………..David Paich and Jeff Porcaro -

Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104 ANTONÍN DVORÁK

I believe Prokofiev is the most imaginative orchestrator of all time. He uses the percussion and the special effects of the strings in new and different ways; always tasteful, never too much of any one thing. His Symphony No. 5 is one of the best illustrations of all of that. JANET HALL, NCS VIOLIN Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104 ANTONÍN DVORÁK BORN September 8, 1841, near Prague; died May 1, 1904, in Prague PREMIERE Composed 1894-1895; first performance March 19, 1896, in London, conducted by the composer with Leo Stern as soloist OVERVIEW During the three years that Dvořák was teaching at the National Conservatory of Music in New York City, he was subject to the same emotions as most other travelers away from home for a long time: invigoration and homesickness. America served to stir his creative energies, and during his stay, from 1892 to 1895, he composed some of his greatest scores: the “New World” Symphony, the Op. 96 Quartet (“American”), and the Cello Concerto. He was keenly aware of the new musical experiences to be discovered in the land far from his beloved Bohemia when he wrote, “The musician must prick up his ears for music. When he walks he should listen to every whistling boy, every street singer or organ grinder. I myself am often so fascinated by these people that I can scarcely tear myself away.” But he missed his home and, while he was composing the Cello Concerto, looked eagerly forward to returning. He opened his heart in a letter to a friend in Prague: “Now I am finishing the finale of the Cello Concerto. -

A Study of Selected Contemporary Compositions for Bassoon by Composers Margi Griebling-Haigh, Ellen Taaffe-Zwilich and Libby

A STUDY OF SELECTED CONTEMPORARY COMPOSITIONS FOR BASSOON BY COMPOSERS MARGI GRIEBLING-HAIGH, ELLEN TAAFFE-ZWILICH AND LIBBY LARSEN by ELIZABETH ROSE PELLEGRINI JENNIFER L. MANN, COMMITTEE CHAIR DON FADER TIMOTHY FEENEY JONATHAN NOFFSINGER THOMAS ROBINSON THEODORE TROST A MANUSCRIPT Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the School of Music in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2018 Copyright Elizabeth Rose Pellegrini 2018 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT In my final DMA recital, I performed Sortilège by Margi Griebling-Haigh (1960), Concerto for Bassoon and Orchestra by Ellen Taaffe-Zwilich (1939), and Concert Piece by Libby Larsen (1950). For each of these works, I give a brief biography of the composer and history of the piece. I contacted each of these composers and asked if they would provide further information on their compositional process that was not already available online. I received responses from Margie Griebling-Haigh and Libby Larsen and had to research information for Ellen Taaffe-Zwilich. I assess the contribution of these works to the body of bassoon literature, summarize the history of the literature, discuss the first compositions for bassoon by women, and discuss perceptions of the instrument today. I provide a brief analysis of these works to demonstrate how they contribute to the literature. I also offer comments from Nicolasa Kuster, one of the founders of the Meg Quigley Vivaldi Competition. Her thoughts as an expert in this field offer insight into why these works require our ardent advocacy. ii DEDICATION This manuscript is dedicated, first and foremost, to all the women over the years who have inspired me.