The Birds of Orkney David Lea and W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Habitats and Species Surveys in the Pentland Firth and Orkney Waters: Updated October 2016

TOPIC SHEET NUMBER 34 V3 SOUTH RONALDSAY Along the eastern coast of the island at 30m the HABITATS AND SPECIES SURVEYS IN THE PENTLAND videos revealed a seabed of coarse sand and scoured rocky outcrops. The sand was inhabited FIRTH AND ORKNEY WATERS by echinoderms and crustaceans, while the rock was generally bare with sparse Alcyonium digitatum (Dead men’s fi nger) and numerous DUNCANSBY HEAD PAPA WESTRAY WESTRAY Echinus esculentus. Dense brittlestar beds were The seabed recorded to the south of Duncansby SANDAY found to the south. Further north at a depth Head is fl at bedrock with patches of sand, of 50 m the seabed took the form of a mosaic cobbles and boulders. The rock surface is quite ROUSAY MAINLAND STRONSAY of rippled sand, bedrock and boulders with bare other than dense patches of red algae, ORKNEY occasional hydroids and bryozoans. clumps of hydroids and dense brittlestar beds. SCAPA FLOW HOY COPINSAY SOUTH RONALDSAY PENTLAND FIRTH STROMA DUNCANSBY HEAD CAITHNESS VIDEO AND PHOTOGRAPH SITES IN SOUTHERN PART OF ANEMONES URTICINA FELINA ON TIDESWEPT SURVEYED AREA CIRCALITTORAL ROCK Introduction mussels off Copinsay, also found off Noss Head. An extensive coverage of loose-lying Data availability References Marine Scotland Science has been collecting red alga was found in the east of Scapa Flow video and photographic stills from the Pentland The biotope classifi cations and the underlying Moore, C.G. (2009). Preliminary assessment of the on muddy sand and sandeels were also found Firth and Orkney Islands as part of a wider video and images are all available through conservation importance of benthic epifaunal species off west Hoy. -

Results of the Seabird 2000 Census – Great Skua

July 2011 THE DATA AND MAPS PRESENTED IN THESE PAGES WAS INITIALLY PUBLISHED IN SEABIRD POPULATIONS OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND: RESULTS OF THE SEABIRD 2000 CENSUS (1998-2002). The full citation for the above publication is:- P. Ian Mitchell, Stephen F. Newton, Norman Ratcliffe and Timothy E. Dunn (Eds.). 2004. Seabird Populations of Britain and Ireland: results of the Seabird 2000 census (1998-2002). Published by T and A.D. Poyser, London. More information on the seabirds of Britain and Ireland can be accessed via http://www.jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-1530. To find out more about JNCC visit http://www.jncc.defra.gov.uk/page-1729. Table 1a Numbers of breeding Great Skuas (AOT) in Scotland and Ireland 1969–2002. Administrative area Operation Seafarer SCR Census Seabird 2000 Percentage Percentage or country (1969–70) (1985–88) (1998–2002) change since change since Seafarer SCR Shetland 2,968 5,447 6,846 131% 26% Orkney 88 2,0001 2,209 2410% 10% Western Isles– 19 113 345 1716% 205% Comhairle nan eilean Caithness 0 2 5 150% Sutherland 4 82 216 5300% 163% Ross & Cromarty 0 1 8 700% Lochaber 0 0 2 Argyll & Bute 0 0 3 Scotland Total 3,079 7,645 9,634 213% 26% Co. Mayo 0 0 1 Ireland Total 0 0 1 Britain and Ireland Total 3,079 7,645 9,635 213% 26% Note 1 Extrapolated from a count of 1,652 AOT in 1982 (Meek et al., 1985) using previous trend data (Furness, 1986) to estimate numbers in 1986 (see Lloyd et al., 1991). -

The Orkney Native Wildlife Project

The Orkney Native Wildlife Project Strategic Environmental Assessment Environmental Report June 2020 1 / 31 Orkney Native Wildlife Project Environmental Report 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Project Summary and Objectives ............................................................................. 4 1.2 Policy Context............................................................................................................ 4 1.3 Related Plans, Programmes and Strategies ............................................................ 4 2. SEA METHODOLOGY ..................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Topics within the scope of assessment .............................................................. 6 2.2 Assessment Approach .............................................................................................. 6 2.3 SEA Objectives .......................................................................................................... 7 2.4 Limitations to the Assessment ................................................................................. 8 3. ENVIRONMENTAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE PROJECT AREA ............................. 8 3.1 Biodiversity, Flora and Fauna ................................................................................... 8 3.2 Population and Human Health .................................................................................. 9 -

Cruising the ISLANDS of ORKNEY

Cruising THE ISLANDS OF ORKNEY his brief guide has been produced to help the cruising visitor create an enjoyable visit to TTour islands, it is by no means exhaustive and only mentions the main and generally obvious anchorages that can be found on charts. Some of the welcoming pubs, hotels and other attractions close to the harbour or mooring are suggested for your entertainment, however much more awaits to be explored afloat and many other delights can be discovered ashore. Each individual island that makes up the archipelago offers a different experience ashore and you should consult “Visit Orkney” and other local guides for information. Orkney waters, if treated with respect, should offer no worries for the experienced sailor and will present no greater problem than cruising elsewhere in the UK. Tides, although strong in some parts, are predictable and can be used to great advantage; passage making is a delight with the current in your favour but can present a challenge when against. The old cruising guides for Orkney waters preached doom for the seafarer who entered where “Dragons and Sea Serpents lie”. This hails from the days of little or no engine power aboard the average sailing vessel and the frequent lack of wind amongst tidal islands; admittedly a worrying combination when you’ve nothing but a scrap of canvas for power and a small anchor for brakes! Consult the charts, tidal guides and sailing directions and don’t be afraid to ask! You will find red “Visitor Mooring” buoys in various locations, these are removed annually over the winter and are well maintained and can cope with boats up to 20 tons (or more in settled weather). -

Breeding Ecology and Extinction of the Great Auk (Pinguinus Impennis): Anecdotal Evidence and Conjectures

THE AUK A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY VOL. 101 JANUARY1984 No. 1 BREEDING ECOLOGY AND EXTINCTION OF THE GREAT AUK (PINGUINUS IMPENNIS): ANECDOTAL EVIDENCE AND CONJECTURES SVEN-AXEL BENGTSON Museumof Zoology,University of Lund,Helgonavi•en 3, S-223 62 Lund,Sweden The Garefowl, or Great Auk (Pinguinusimpen- Thus, the sad history of this grand, flightless nis)(Frontispiece), met its final fate in 1844 (or auk has received considerable attention and has shortly thereafter), before anyone versed in often been told. Still, the final episodeof the natural history had endeavoured to study the epilogue deservesto be repeated.Probably al- living bird in the field. In fact, no naturalist ready before the beginning of the 19th centu- ever reported having met with a Great Auk in ry, the GreatAuk wasgone on the westernside its natural environment, although specimens of the Atlantic, and in Europe it was on the were occasionallykept in captivity for short verge of extinction. The last few pairs were periods of time. For instance, the Danish nat- known to breed on some isolated skerries and uralist Ole Worm (Worm 1655) obtained a live rocks off the southwesternpeninsula of Ice- bird from the Faroe Islands and observed it for land. One day between 2 and 5 June 1844, a several months, and Fleming (1824) had the party of Icelanderslanded on Eldey, a stackof opportunity to study a Great Auk that had been volcanic tuff with precipitouscliffs and a flat caught on the island of St. Kilda, Outer Heb- top, now harbouring one of the largestsgan- rides, in 1821. nettles in the world. -

Where to Go: Puffin Colonies in Ireland Over 15,000 Puffin Pairs Were Recorded in Ireland at the Time of the Last Census

Where to go: puffin colonies in Ireland Over 15,000 puffin pairs were recorded in Ireland at the time of the last census. We are interested in receiving your photos from ANY colony and the grid references for known puffin locations are given in the table. The largest and most accessible colonies here are Great Skellig and Great Saltee. Start Number Site Access for Pufferazzi Further information Grid of pairs Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Great Skellig V247607 4,000 worldheritageireland.ie/skellig-michael check local access arrangements Puffin Island - Kerry V336674 3,000 Access more difficult Boat trips available but landing not possible 1,522 Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Great Saltee X950970 salteeislands.info check local access arrangements Mayo Islands l550938 1,500 Access more difficult Illanmaster F930427 1,355 Access more difficult Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Cliffs of Moher, SPA R034913 1,075 check local access arrangements Stags of Broadhaven F840480 1,000 Access more difficult Tory Island and Bloody B878455 894 Access more difficult Foreland Kid Island F785435 370 Access more difficult Little Saltee - Wexford X968994 300 Access more difficult Inishvickillane V208917 170 Access more difficult Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Horn Head C005413 150 check local access arrangements Lambay Island O316514 87 Access more difficult Pig Island F880437 85 Access more difficult Inishturk Island L594748 80 Access more difficult Clare Island L652856 25 Access more difficult Beldog Harbour to Kid F785435 21 Access more difficult Island Mayo: North West F483156 7 Access more difficult Islands Ireland’s Eye O285414 4 Access more difficult Howth Head O299389 2 Access more difficult Wicklow Head T344925 1 Access more difficult Where to go: puffin colonies in Inner Hebrides Over 2,000 puffin pairs were recorded in the Inner Hebrides at the time of the last census. -

Of Orkn Y 2015 Information and Travel Guide to the Smaller Islands of Orkney

The Islands of ORKN Y 2015 information and travel guide to the smaller islands of Orkney For up to date Orkney information visit www.visitorkney.com • www.orkney.com • www.discover-orkney.com The Islands of ORKN Y Approximate driving times From Kirkwall and Stromness to Ferry Terminals at: • Tingwall 30 mins • Houton 20 mins From Stromness to Kirkwall Airport • 40 mins From Kirkwall to Airport • 10 mins The Islands of looking towards evie and eynhallow from the knowe of yarso on rousay - drew kennedy 1 Contents Contents Out among the isles . 2-5 will be happy to assist you find the most At catching fish I am so speedy economic travel arrangements: A big black scarfie fromEDAY . 6-9 www.visitscotland.com/orkney If you want something with real good looks You can’t go wrong with FLOTTA fleuks . 10-13 There’s not quite such a wondrous thing as a beautiful young GRAEMSAY gosling . 14-17 To take the head off all their big talk Just pay attention to the wise HOY hawk . 14-17 The Countryside Code All stand to the side and reveal Please • close all gates you open. Use From far NORTH RONALDSAY a seal . 18-21 stiles when possible • do not light fires When feeling low or down in the dumps • keep to paths and tracks Just bake some EGILSAY burstin lumps . 22-25 • do not let your dog worry grazing animals You can say what you like, I don’t care • keep mountain bikes on the For I’m a beautiful ROUSAY mare . -

Sound of Gigha Proposed Special Protection Area (Pspa) NO

Sound of Gigha Proposed Special Protection Area (pSPA) NO. UK9020318 SPA Site Selection Document: Summary of the scientific case for site selection Document version control Version and Amendments made and author Issued to date and date Version 1 Formal advice submitted to Marine Scotland on Marine draft SPA. Nigel Buxton & Greg Mudge. Scotland 10/07/14 Version 2 Updated to reflect change in site status from draft Marine to proposed and addition of SPA reference Scotland number in preparation for possible formal 30/06/15 consultation. Shona Glen, Tim Walsh & Emma Philip Version 3 Creation of new site selection document. Emma Susie Whiting Philip 17/05/16 Version 4 Document updated to address requirements of Greg revised format agreed by Marine Scotland. Mudge Kate Thompson & Emma Philip 17/06/16 Version 5 Quality assured Emma Greg Mudge Philip 17/6/16 Version 6 Final draft for approval Andrew Emma Philip Bachell 22/06/16 Version 7 Final version for submission to Marine Scotland Marine Scotland, 24/06/16 Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 2. Site summary ........................................................................................................ 2 3. Bird survey information ....................................................................................... 5 4. Assessment against the UK SPA Selection Guidelines .................................... 6 5. Site status and boundary ................................................................................. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Layout 1 Copy

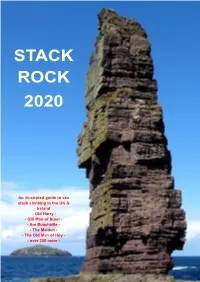

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

Orkney Greylag Goose Survey Report 2015

The abundance and distribution of British Greylag Geese in Orkney, August 2015 A report by the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust to Scottish Natural Heritage Carl Mitchell 1, Alan Leitch 2, & Eric Meek 3 November 2015 1 The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust, Slimbridge, Gloucester, GL2 7BT 2 The Willows, Finstown, Orkney, KY17, 2EJ 3 Dashwood, 66 Main Street, Alford, Aberdeenshire, AB33 8AA 1 © The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This publication should be cited as: Mitchell, C., A.J. Leitch & E. Meek. 2015. The abundance and distribution of British Greylag Geese in Orkney, August 2015. Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust Report, Slimbridge. 16pp. Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust Slimbridge Gloucester GL2 7BT T 01453 891900 F 01453 890827 E [email protected] Reg. Charity no. 1030884 England & Wales, SC039410 Scotland 2 Contents Summary ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Methods ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Field counts ...................................................................................................................................... -

Kirkwall to Westray

Sailing notes downloaded from the Orkney Marinas website. www.orkneymarinas.co.uk Kirkwall to Westray We hope you find these notes helpful and of interest to you while planning your sailing trip to Orkney. Please note they are not intended to be used for navigation The quickest journey time from Kirkwall to Pierowall is on the ebb, leaving Kirkwall to cross the Westray Firth on the last of the ebb as by the time the tide is running N.E through Fersness and Weatherness sounds. It makes little difference to the journey times when leaving Kirkwall whether one goes out through Vasa or the Bouyed channel nearer Gairsay, Vasa probably best on the ebb, Bouyed best on the flood. When crossing the Westray Firth if there is any westerly type weather it is advisable to keep well over to the Green Holmes and across to Seal Skerry on the west side of Eday. In westerly conditions, the further west one goes the worse the conditions are with a very rough edge of tide running from Seal Skerry to the SW corner of Rusk Holm and NW to Rull Noost off Wart Holm especially during the last 2 hours of the ebb. Best avoided. If conditions are not adverse let the tide carry you to the west of Rusk Holm and NE to Weatherness, this is the quickest route. Fersness or Weatherness sounds can be used with the deeper water in Fersness. The tide in both places tends to run east for 4 hours and west for 8 hours. If sailing from Kirkwall during flood tide your journey time will be somewhat longer.