Identity, Ideology, and Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-2010 The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira Shannon Victoria Stevens University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Repository Citation Stevens, Shannon Victoria, "The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira" (2010). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 371. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/1606942 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RHETORICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF GOJIRA by Shannon Victoria Stevens Bachelor of Arts Moravian College and Theological Seminary 1993 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Communication Studies Department of Communication Studies Greenspun College of Urban Affairs Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2010 Copyright by Shannon Victoria Stevens 2010 All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE COLLEGE We recommend the thesis prepared under our supervision by Shannon Victoria Stevens entitled The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication Studies David Henry, Committee Chair Tara Emmers-Sommer, Committee Co-chair Donovan Conley, Committee Member David Schmoeller, Graduate Faculty Representative Ronald Smith, Ph. -

From 'Scottish' Play to Japanese Film: Kurosawa's Throne of Blood

arts Article From ‘Scottish’ Play to Japanese Film: Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood Dolores P. Martinez Emeritus Reader, SOAS, University of London, London WC1H 0XG, UK; [email protected] Received: 16 May 2018; Accepted: 6 September 2018; Published: 10 September 2018 Abstract: Shakespeare’s plays have become the subject of filmic remakes, as well as the source for others’ plot lines. This transfer of Shakespeare’s plays to film presents a challenge to filmmakers’ auterial ingenuity: Is a film director more challenged when producing a Shakespearean play than the stage director? Does having auterial ingenuity imply that the film-maker is somehow freer than the director of a play to change a Shakespearean text? Does this allow for the language of the plays to be changed—not just translated from English to Japanese, for example, but to be updated, edited, abridged, ignored for a large part? For some scholars, this last is more expropriation than pure Shakespeare on screen and under this category we might find Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood (Kumonosu-jo¯ 1957), the subject of this essay. Here, I explore how this difficult tale was translated into a Japanese context, a society mistakenly assumed to be free of Christian notions of guilt, through the transcultural move of referring to Noh theatre, aligning the story with these Buddhist morality plays. In this manner Kurosawa found a point of commonality between Japan and the West when it came to stories of violence, guilt, and the problem of redemption. Keywords: Shakespeare; Kurosawa; Macbeth; films; translation; transcultural; Noh; tragedy; fate; guilt 1. -

SKIP CITY INTERNATIONAL D-Cinema FESTIVAL 2017

June 1, 2017 For Press (Page 1 of 5) SKIP CITY INTERNATIONAL D-Cinema FESTIVAL 2017 Running from July 15 to 23 – Full Iine-up announced! ★“Filmmakers Making Waves”: 6 films by flourishing festival alumni nominated in past editions to screen! ★“D-Cinema – New Currents”: 6 VR (virtual reality) films from Japan and abroad! ★ 810 films submitted from 85 countries and regions for the three competition sections! 12 selected films, including 3 countries nominated for the first time, in the Feature Length Competition! ★“ANIMA!”, the Opening Gala Film produced by the Festival Committee will have its world premiere! Launched in 2004 as one of the world’s first film festivals to focus solely on films shot on digital in order to discover and nurture emerging talent, SKIP CITY INTERNATIONAL D-Cinema FESTIVAL in troduced to Japan, Nuri Bilge Ceylan, winner of three awards including Palme d'Or at the Cannes International Film Festival, and numerous new Japanese talents like Kazuya Shiraishi (“Twisted Justice”) and Ryota Nakano (“Her Love Boils Bathwater”). The 14th edition of the Festival will be held over 9 days from Saturday, July 15, to Sunday, July 23. The press conference was held on Thursday, June 1, at the Todofuken Kaikan in Nagata-cho, Tokyo, to announce its full line-up. The details are as follows. Please kindly cover on your magazine as we are sure to discover more newcomers at this year's festival. “Filmmakers Making Waves”: Films by flourishing festival alumni to be screened! In recent years, filmmakers whose previous works screened at our festival have been gaining recognition. -

DVD Press Release

DVD press release Kurosawa Classic Collection 5-disc box set Akira Kurosawa has been hailed as one of the greatest filmmakers ever by critics all over the world. This, the first of two new Kurosawa box sets from the BFI this month, brings together five of his most profound masterpieces, each exploring the complexities of life, and includes two previously unreleased films. An ideal introduction to the work of the master filmmaker, the Kurosawa Classic Collection contains Ikiru (aka Living), I Live in Fear and Red Beard along with the two titles new to DVD, the acclaimed Maxim Gorky adaptation The Lower Depths and Kurosawa’s first colour film Dodes’ka-den (aka Clickety-clack). The discs are accompanied by an illustrated booklet of film notes and credits and selected filmed introductions by director Alex Cox. Ikiru (Living), 1952, 137 mins Featuring a beautifully nuanced performance by Takashi Shimura as a bureaucrat diagnosed with stomach cancer, Ikiru is an intensely lyrical and moving film which explores the nature of existence and how we find meaning in our lives. I Live in Fear (Ikimono no Kiroku), 1955, 99 mins Made at the height of the Cold War, with the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki still a recent memory, Toshiro Mifune delivers an outstanding performance as a wealthy foundry owner who decides to move his entire family to Brazil to escape the nuclear holocaust which he fears is imminent. The Lower Depths (Donzonko), 1957, 120 mins Once again working with Toshiro Mifune, Kurosawa adapts Maxim Gorky’s classic play of downtrodden humanity. -

Yoshioka, Shiro. "Princess Mononoke: a Game Changer." Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’S Monster Princess

Yoshioka, Shiro. "Princess Mononoke: A Game Changer." Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’s Monster Princess. By Rayna Denison. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 25–40. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501329753.ch-001>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 01:01 UTC. Copyright © Rayna Denison 2018. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 25 Chapter 1 P RINCESS MONONOKE : A GAME CHANGER Shiro Yoshioka If we were to do an overview of the life and works of Hayao Miyazaki, there would be several decisive moments where his agenda for fi lmmaking changed signifi cantly, along with how his fi lms and himself have been treated by the general public and critics in Japan. Among these, Mononokehime ( Princess Mononoke , 1997) and the period leading up to it from the early 1990s, as I argue in this chapter, had a great impact on the rest of Miyazaki’s career. In the fi rst section of this chapter, I discuss how Miyazaki grew sceptical about the style of his fi lmmaking as a result of cataclysmic changes in the political and social situation both in and outside Japan; in essence, he questioned his production of entertainment fi lms featuring adventures with (pseudo- )European settings, and began to look for something more ‘substantial’. Th e result was a grave and complex story about civilization set in medieval Japan, which was based on aca- demic discourses on Japanese history, culture and identity. -

Aichi Triennale 2019 Has Announced the List of Additional Artists

Aichi Triennale 2019 Press Release _ Participating Artists As of March 27, 2019 Aichi Triennale 2019 Has Announced the List of Additional Artists Aichi Triennale—an international contemporary art festival that occurs once every three years and is one of the largest of its kind—has been showcasing the cutting edge of the arts since 2010, through its wide-ranging program that spans international contemporary visual art, film, the performing arts, music, and more. This fourth iteration of the festival welcomes journalist and media activist Daisuke Tsuda as its artistic director. By choosing “Taming Y/Our Passion” as the festival’s theme, Tsuda seeks to address “the sensationalization of media that at present plagues and polarizes people around the world.” He hopes that by “employing the capacity of art— a venture that, capable of encompassing every possible phenomenon, eschews framing the world through dichotomies—to speak to our compassion, thus potentially yielding clues to solving this predicament.” Aichi Triennale 2019 announced the addition of 47 artists to its lineup on 27 March 2019; the list now comprises a total of 79 artists. Outline of Aichi Triennale 2019 http://aichitriennale.jp/ Theme | Taming Y/Our Passion Artistic Director | TSUDA Daisuke (Journalist / Media Activist) Period | August 1 (Thursday) to October 14 (Monday, public holiday), 2019 [75 days] Main Venues | Aichi Arts Center; Nagoya City Art Museum; Toyota Municipal Museum of Art and off-site venues in Aichi Prefecture, JAPAN Organizer | Aichi Triennale Organizing -

Film Noir in Postwar Japan Imogen Sara Smith

FILM NOIR IN POSTWAR JAPAN Imogen Sara Smith uined buildings and neon signs are reflected in the dark, oily surface of a stagnant pond. Noxious bubbles rise to the surface of the water, which holds the drowned corpses of a bicycle, a straw sandal, and a child’s doll. In Akira Kurosawa’s Drunken Angel (1948), this fetid swamp is the center of a disheveled, yakuza-infested Tokyo neighborhood and a symbol of the sickness rotting the soul of postwar Japan. It breeds mosquitos, typhus, and tuberculosis. Around its edges, people mourn their losses, patch their wounds, drown their sorrows, and wrestle with what they have been, what they are, what they want to be. Things looked black for Japan in the aftermath of World War II. Black markets sprang up, as they did in every war-damaged country. Radioactive “black rain” fell after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Black Spring was the title of a 1953 publication that cited Japanese women’s accounts of rape by Occupation forces. In “Early Japanese Noir” (2014), Homer B. Pettey wrote that in Japanese language and culture, “absence, failure, or being wrong is typified by blackness, as it also indicates the Japanese cultural abhorrence for imperfection or defilement, as in dirt, filth, smut, or being charred.” In films about postwar malaise like Drunken Angel, Kenji Mizoguchi’s Women of the Night (1948), and Masaki Kobayashi’s Black River (1957), filth is everywhere: pestilent cesspools, burnt-out rubble, grungy alleys, garbage-strewn lots, sleazy pleasure districts, squalid shacks, and all the human misery and depravity that go along with these settings. -

A Study of Akira Kurosawa's Ikiru on Its Fiftieth Anniversary

PERSONAL TRANSFORMATION THROUGH AN ENCOUNTER WITH DEATH: A STUDY OF AKIRA KUROSAWA’S IKIRU ON ITS FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY Francis G. Lu, M.D. San Francisco, California ABSTRACT: Akira Kurosawa’s film 1952 Ikiru (the intransitive verb ‘‘to live’’ in Japanese) presents the viewer with a seeming paradox: a heightened awareness of one’s mortality can lead to living a more authentic and meaningful life. While confronting these existential issues, our hero Watanabe traces the path of the Hero’s Journey as described by the mythologist Joseph Campbell among others. Simultaneous to this outward arc, Watanabe experiences an inward arc of transformation of consciousness taking him from the individual persona to the transpersonal. Kurosawa skillfully blends aesthetic concepts and sensibilities both Western (Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Goethe’s Faust) and Eastern (Noh, Zen Buddhist) to create one of the greatest of cinematic masterworks. PROLOGUE ‘‘Awareness of death is the very bedrock of the path. Until you have developed this awareness, all other practices are obstructed.’’ —The Dalai Lama ‘‘Whoever rightly understands and celebrates death, at the same time magnifies life.’’ —Rainer Maria Rilke ‘‘As long as you do not know how to die and come to life again, you are but a poor guest on this dark earth.’’ —Johann Wolfgang von Goethe ‘‘Eternity is in love with the productions of time.’’ —William Blake ‘‘Sometimes I think of my death. I think of ceasing to be ... and it is from these thoughts that Ikiru came.’’ —Akira Kurosawa INTRODUCTION Ikiru is a 1952 Japanese film directed by Akira Kurosawa, who is widely acknowledged as one of the cinema’s greatest directors; the screenplay was written by Kurosawa, Shinobu Hashimoto and Hideo Oguni. -

Language Lab Video Catalog

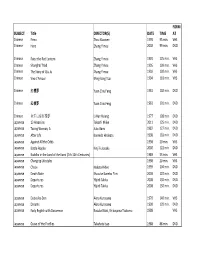

FORM SUBJECT Title DIRECTOR(S) DATE TIME AT Chinese Ermo Zhou Xiaowen 1995 95 min. VHS Chinese Hero Zhang Yimou 2002 99 min. DVD Chinese Raise the Red Lantern Zhang Yimou 1991 125 min. VHS Chinese Shanghai Triad Zhang Yimou 1995 109 min. VHS Chinese The Story of Qiu Ju Zhang Yimou 1992 100 min. VHS Chinese Vive L'Amour Ming‐liang Tsai 1994 118 min. VHS Chinese 紅樓夢 Yuan Chiu Feng 1961 102 min. DVD Chinese 紅樓夢 Yuan Chiu Feng 1961 101 min. DVD Chinese 金玉良緣紅樓夢 Li Han Hsiang 1977 108 min. DVD Japanese 13 Assassins Takashi Miike 2011 125 min. DVD Japanese Taxing Woman, AJuzo Itami 1987 127 min. DVD Japanese After Life Koreeda Hirokazu 1998 118 min. DVD Japanese Against All the Odds 1998 20 min. VHS Japanese Battle Royale Kinji Fukasaku 2000 122 min. DVD Japanese Buddha in the Land of the Kami (7th‐12th Centuries) 1989 53 min. VHS Japanese Changing Lifestyles 1998 20 min. VHS Japanese Chaos Nakata Hideo 1999 104 min. DVD Japanese Death Note Shusuke Kaneko Film 2003 120 min. DVD Japanese Departures Yôjirô Takita 2008 130 min. DVD Japanese Departures Yôjirô Takita 2008 130 min. DVD Japanese Dodes'ka‐Den Akira Kurosawa 1970 140 min. VHS Japanese Dreams Akira Kurosawa 1990 120 min. DVD Japanese Early English with Doraemon Kusuba Kôzô, Shibayama Tsutomu 1988 VHS Japanese Grave of the Fireflies Takahata Isao 1988 88 min. DVD FORM SUBJECT Title DIRECTOR(S) DATE TIME AT Japanese Happiness of the Katakuris Takashi Miike 2001 113 min. DVD Japanese Ikiru Akira Kurosawa 1952 143 min. -

Exploring the Japanese Heritage Film

῏ῑῒΐ ῐ ῍ ῍῎ῌῌ῏῎ Cinema Studies, no.1 Exploring the Japanese Heritage Film Mai K6ID Introduction The issue of heritage film has become one of the most crucial and frequently discussed topics in Film Studies. Not only has the argu- ment about British ῍or English῎ heritage film been developed by many researchers,1 but the idea of the heritage film has also begun to be applied to the cinema of other countries. A remarkable example in the latter direction is Guy Austin’s examination of la tradition de qualité in French cinema as a heritage genre ῍142῎ῌ One of the main aims of this article is to provide support for the proposal that the concept of heritage films should be applied internationally, rather than solely to the British cinema. This is because I believe the idea of the heritage film could be one of the main scholarly research field in Film Studies as a whole, as it encompasses a large number of areas including representation, gender, genre, reception, marketing, politics and tourism. Like canonical research fields in Film Studies such as Film Noir or The New Wave, the idea of The Heritage Film establishes an alternative method of examining and understanding film. In order to demonstrate the capability of the heritage film con- cept, and in particular its adaptability beyond the confines of British cinema, this article aims to apply it to Japanese cinema. In con- sideration of what kind or type of Japanese cinema might be eligible as heritage film, the most likely answer is Jidaigeki, which can loosely be understood as period dramas. -

By Shinya Tsukamoto

“Killing” (Zan) by Shinya Tsukamoto © 2018 SHINYA TSUKAMOTO / KAIJYU THEATER Director: Shinya Tsukamoto Country: Japan Genre: Drama, Sword action Duration: 80min. Actors – Filmography: (selective) Sosuke Ikematsu (Mokunoshin) - The Tokyo Night Sky is Always The Densest Shade of Blue (‘17), The Long Excuse (‘16), Death Note: Light Up the New World (‘16), The Last Samurai (‘03) Yu Aoi (Yu) - Birds Without Names (‘17), Tokyo! (by Bong Joonho ’08), Hula Girls (’06), Hana and Alice (’04) Tatsuya Nakamura (Genda) - Fires on the Plain (‘14), Bullet Ballet (’99) Shinya Tsukamoto (Sawamura) - Silence (by Martin Scorsese ’16), Shin Godzilla (’16), Fires on the Plain (‘14) [International Sales] [Production] NIKKATSU CORPORATION Kaijyu Theater 3-28-12, Hongo, Bunkyo-ku Tokyo 113-0033, JAPAN Phone:+81-3-5689-1014 Emico Kawai & Taku Kato [email protected] FESTIVAL Mami Furukawa [email protected] < Synopsis > After about 250 years of peace in Japan, samurai warriors in the mid-19th century were impoverished. Consequently, many left their masters to become wandering ronin. Mokunoshin Tsuzuki (played by Sosuke Ikematsu) is one such samurai. He survives by helping farmers in a village out of Edo. To maintain his swordsmanship skills, Mokunoshin spars daily with Ichisuke (Ryusei Maeda), a farmer's son. Ichisuke's sister Yu (Yu Aoi) watches them train with a hint of disapproval although there's an unspoken attraction between her and Mokunoshin. While farm life is peaceful, there is monumental turmoil in Japan. The US Navy has sent Commodore Perry to Japan to insist that it trades with them. This in turn causes civil unrest. -

Personal Transformation Through an Encounter with Death: Cinematic and Psychotherapy Case Studies

PERSONAL TRANSFORMATION THROUGH AN ENCOUNTER WITH DEATH: CINEMATIC AND PSYCHOTHERAPY CASE STUDIES Sanford R. Weimer Los Angeles, California Francis G. Lu San Francisco, California The psychotherapist is in a privileged position to learn about the most profound issues of human existence and to use that knowledge to help patients. Not all of the most important lessons we learn in our quest to help our patients come from scientific literature. One of the delights of being a psycho therapist is the opportunity to learn from art and philosophy, as well as our own patients. As students of film and as active clinicians, the authors have an unusual opportunity to contrast the incisive observations made by Akira Kurosawa in the film, exploring Ikiru, and the psychotherapy of a remarkable patient. Many similarities authors have noted the value of insights from psychotherapy in between Ikiru understanding art (Weimer, 1978).This paper will explore the and a similarities between the film experience of Ikiru and the last documented year of a man's life which was extensively documented in psychotherapy psychotherapy with one of the authors. Scholl (1984) has case recently reviewed how the humanities have portrayed the theme of death in Western culture. Both the patient and the chief protagonist of the film were articulate men faced at the peak of career with a fatal cancer. The character in the film, Mr. Watanabe, is shaken out ofa life of meaningless complacency to create meaning ultimately through a series of actions he takes when faced with death. The patient, Mr. Lazarus, like Mr. Watanabe, was a successful middle management executive who met the challenge of his Copyright © 1987Transpersonal Institute The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 1987, Vol.