Protestant Nonconformity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hythe Ward Hythe Ward

Cheriton Shepway Ward Profile May 2015 Hythe Ward Hythe Ward -2- Hythe Ward Foreword ..........................................................................................................5 Brief Introduction to area .............................................................................6 Map of area ......................................................................................................7 Demographic ...................................................................................................8 Local economy ...............................................................................................11 Transport links ..............................................................................................16 Education and skills .....................................................................................17 Health & Wellbeing .....................................................................................22 Housing .........................................................................................................33 Neighbourhood/community ..................................................................... 36 Planning & Development ............................................................................41 Physical Assets ............................................................................................ 42 Arts and culture ..........................................................................................48 Crime .......................................................................................................... -

Besford Gardens, Trinity Street, Belle Vue, Shrewsbury, SY3 7PQ

ESTATE & LETTINGS AGENTS | CHARTERED SURVEYORS HOW TO FIND THIS PROPERTY From the town centre, the development is best approached over the English Bridge and around the gyratory system into Coleham Head. Continue along Belle Vue Road, eventually turning left into Trinity Street. Continue to the top of Trinity Street and Besford Gardens will be found on the right hand side. SERVICES We understand that mains water, electricity, drainage and natural gas are connected. In partnership with Floreat Homes TENURE We are advised that the properties are freehold and this will be confirmed by the vendors' solicitors during pre-contract enquiries LOCAL AUTHORITIES Shropshire Council Frankwell, Shrewsbury Tel 0345 678 9000 2014-05-23 IMPORTANT NOTICE Our particulars have been prepared with care and are checked where possible by the vendor. They are however, intended as a guide. Measurements, areas and distances are approximate. Appliances, plumbing, heating and electrical fittings are noted, but not tested. Legal matters including Rights of Way, Covenants, Easements, Wayleaves and Planning matters have not been verified and you should take advice from your legal representatives and Surveyor. DO YOU HAVE A PROPEPROPERTYRTY TO SELL ??? We will always be pleased to give you a no obligation market assessment of your existing property to help you with your decision to move DO YOU NEED A SURVEYOR ? We are Chartered Surveyors and will be pleased to give advice on Surveys, Homebuyers Reports and other professional matters. Besford Gardens, Trinity Street, Belle Vue, Shrewsbury, SY3 7PQ To view this property please call us on 01743 236800 Ref: T 4971/SL/GA 3 Bedroomed, Semi-detached House Besford Gardens is an attractive development of 11 houses, set in the popular and established conservation area of Belle Vue. -

The Implementation and Impact of the Reformation in Shropshire, 1545-1575

The Implementation and Impact of the Reformation in Shropshire, 1545-1575 Elizabeth Murray A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts United Faculty of Theology The Melbourne College of Divinity October, 2007 Abstract Most English Reformation studies have been about the far north or the wealthier south-east. The poorer areas of the midlands and west have been largely passed over as less well-documented and thus less interesting. This thesis studying the north of the county of Shropshire demonstrates that the generally accepted model of the change from Roman Catholic to English Reformed worship does not adequately describe the experience of parishioners in that county. Acknowledgements I am grateful to Dr Craig D’Alton for his constant support and guidance as my supervisor. Thanks to Dr Dolly Mackinnon for introducing me to historical soundscapes with enthusiasm. Thanks also to the members of the Medieval Early Modern History Cohort for acting as a sounding board for ideas and for their assistance in transcribing the manuscripts in palaeography workshops. I wish to acknowledge the valuable assistance of various Shropshire and Staffordshire clergy, the staff of the Lichfield Heritage Centre and Lichfield Cathedral for permission to photograph churches and church plate. Thanks also to the Victoria & Albert Museum for access to their textiles collection. The staff at the Shropshire Archives, Shrewsbury were very helpful, as were the staff of the State Library of Victoria who retrieved all the volumes of the Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological Society. I very much appreciate the ongoing support and love of my family. -

IT Venues in Shropshire

IT Venues in Shropshire Shropshire Broadplaces, available at 34 locations across Shropshire, some with a drop-in service. Tel. 01743 252 571. Email [email protected]. Website: www.shropshirebroadplaces.org.uk Enterprise House, Station Street, Bishop’s Castle, Shropshire, SY9 5AQ. Tel 01588 638 038 Email: [email protected]. Website www.bishopscastle.co.uk They are a UK Online centre and offer one-one and small group IT help. Whateverage Tel. 01588 630 437 Email: [email protected] Website www.whateverage.co.uk Shrewsbury Library, Castle Gates, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY1 2AS. Tel. 01743 255 300. Email: [email protected] They offer free public access computers and internet and Wi-Fi access. AgeUK Tel. 01743 233 123 Computer classes for the over 55’s- small daytime classes of 4 students at a cost of £18 for four two-hour sessions. Held at Shrewsbury Library, Louise House and Ludlow Library. Booking essential. Gateway Education and Arts Centre, Chester Street, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY1 1NB. Tel. 01743 355 159/ 01743 361 120. Website: www.shropshire.gov.uk. They offer numerous IT courses. Discounts available for people claiming certain benefits. Castlefields Cyber-Cafe, 69 New Park Street, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY1 2LE. Tel. 01743 240 586 Tuesdays 1.00pm-3.00pm- Silver Surfers Session with support for beginners. All over 55’s welcome. Riversway Elim Church, Lancaster Road, Harlescott, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY1 3LE. Tel. 01743 463 970 Offer drop-in with support and free online courses. Open Monday-Friday. Get Shropshire Online Groups, Shropshire RCC Offices, Shrewsbury Business Park, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY2 6LG. -

POLITICS, SOCIETY and CIVIL WAR in WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History

Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History Series editors ANTHONY FLETCHER Professor of History, University of Durham JOHN GUY Reader in British History, University of Bristol and JOHN MORRILL Lecturer in History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow and Tutor of Selwyn College This is a new series of monographs and studies covering many aspects of the history of the British Isles between the late fifteenth century and the early eighteenth century. It will include the work of established scholars and pioneering work by a new generation of scholars. It will include both reviews and revisions of major topics and books which open up new historical terrain or which reveal startling new perspectives on familiar subjects. It is envisaged that all the volumes will set detailed research into broader perspectives and the books are intended for the use of students as well as of their teachers. Titles in the series The Common Peace: Participation and the Criminal Law in Seventeenth-Century England CYNTHIA B. HERRUP Politics, Society and Civil War in Warwickshire, 1620—1660 ANN HUGHES London Crowds in the Reign of Charles II: Propaganda and Politics from the Restoration to the Exclusion Crisis TIM HARRIS Criticism and Compliment: The Politics of Literature in the Reign of Charles I KEVIN SHARPE Central Government and the Localities: Hampshire 1649-1689 ANDREW COLEBY POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, i620-1660 ANN HUGHES Lecturer in History, University of Manchester The right of the University of Cambridge to print and sell all manner of books was granted by Henry VIII in 1534. -

2013 Parish Plan.Indd

Withington Parish Plan 2013 1 Contents 3 Introduction 4 Review of 2008/9 Parish Plan 5 2013 Parish Plan objectives 6 Analysis of 2013 Parish Plan questionnaire 8 A brief history of Withington 12 Index of parish properties and map 14 The Countryside Code 15 Rights of Way 16 Village amenities and contacts 2 The Withington Parish Plan 2013 The Withington Parish Five Year Plan was first published in 2003 then revised and re- published in July 2008 and has now been updated in 2013. The Parish Plan is an important document as it states the views of the residents of Withington Parish and its future direction. It also feeds directly into the Shrewsbury Area Place Plan, which is used by Shropshire Council Departments when reviewing requirements for such projects as road improvement, housing and commercial planning, water and sewerage. This updated plan was produced by analysing answers to the questionnaire distributed to each household in March 2013. Of the 91 questionnaires distributed, 59 were completed and returned. The Shropshire Rural Community Council (RCC) carried out an independent analysis of the results using computer software specifically designed for this purpose. The Parish Plan is also published on the Withington website www.withingtonshropshire.co.uk 3 Withington 2008 Parish Plan: Review of progress Progress was determined by asking Parishioners to indicate their level of satisfaction as to whether the 8 objectives contained in the 2008 Parish Plan had been achieved (see table below) OBJECTIVE ACHIEVEMENTS HOUSING AND Oppose any further housing or commer- • All housing/commercial development applications have COMMERCIAL cial development. -

Richard Baxter and Antinomianism

RICHARD BAXTER (1615-1691) Dr Williams's Library Other ages have but heard of Antinomian doctrines, but have not seen what practica11 birth they travailed with as we have done.... The groanes, teares and blood of the Godly; the Scornes of the ungodly; the sorrow of our friendes; the Derision of our enemies; the stumbling of the weake, the hardening of the wicked; the backsliding of some; the desperate Blasphemyes and profanenes[s] of others; the sad desolations of Christs Ch urches, and woefull scanda11 that is fallen on the Christian profession, are all the fruites of this Antinomian plant. Richard Baxter, 1651 DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF MY FATHER DOUGLAS JOHN COOPER RICHARD BAXTER AND ANTINOMIANISM A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Tim Cooper-::::- University of Canterbury 1997 BX S?-O~+ . 1~3 ,c~'1:{8 CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ii A NOTE ON QUOTATIONS AND REFERENCES iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS IV ABSTRACT V INTRODUCTION 1 -PART ONE- CHAPTER: I mSTORIOGRAPIHCAL INHERITANCE 11 II THE ANTINOMIAN WORLD 50 III PERSONALITY AND POLEMIC 91 -PARTTWO- IV ARMIES, ANTINOMIANS AND APHORISMS The 1640s 144 V DISPUTES AND DIS SIP ATION The 1650s 194 VI RECRUDESCENCE The Later Seventeenth Century 237 CONCLUSION 294 APPENDIX: A THE RELIQUIAE BAXTERlANAE (1696) 303 B UNDATED TREATISE 309 BmLIOGRAPHY 313 1 9 SEP ZOOO Abbreviations: BJRL Bulletin ofthe John Rylands Library BQ Baptist Quarterly CCRE N. H. Keeble and Geoffrey F. Nuttall (eds), Calendar ofthe Correspondence ofRichard Baxter, 2 vols, Oxford, 1991. DNB L. Stephens and S. Lee (eds), Dictionary ofNational Biography, 23 vols, 1937-1938. -

Church Historical Writing in the English Transatlantic World During the Age of Enlightenment1

CSCH President’s Address 2012 Church Historical Writing in the English Transatlantic World during the Age of Enlightenment1 DARREN W. SCHMIDT The King’s University College My research stemming from doctoral studies is focused on English- speaking evangelical use, interpretation, and production of church history in the eighteenth century, during which religious revivals on both sides of the North Atlantic signalled new developments on many fronts. Church history was of vital importance for early evangelicals, in ways similar to earlier generations of Protestants beginning with the Reformation itself. In the eighteenth century nerves were still sensitive from the religious and political intrigues, polemic, and outright violence in the seventeenth- century British Isles and American colonies; terms such as “Puritan” and “enthusiast” maintained the baggage of suspicion. Presumed to be guilty by association, evangelical leaders were compelled to demonstrate that the perceived “surprising work of God” in their midst had a pedigree: they accordingly construed their experience as part of a long narrative of religious ebb and flow, declension and revival. Time and time again, eighteenth-century evangelicals turned to the pages of the past to vindicate and to validate their religious identity.2 Browsing through historiographical studies, one is hard-pressed to find discussion of eighteenth-century church historical writing. There is general scholarly agreement that the Protestant Reformation gave rise to a new historical interest. In answer to Catholic charges of novelty, Historical Papers 2012: Canadian Society of Church History 188 Church Historical Writing in the English Transatlantic World Protestants critiqued aspects of medieval Catholicism and sought to show their continuity with early Christianity. -

Congregationalism in Edwardian Hampshire 1901-1914

FAITH AND GOOD WORKS: CONGREGATIONALISM IN EDWARDIAN HAMPSHIRE 1901-1914 by ROGER MARTIN OTTEWILL A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham May 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract Congregationalists were a major presence in the ecclesiastical landscape of Edwardian Hampshire. With a number of churches in the major urban centres of Southampton, Portsmouth and Bournemouth, and places of worship in most market towns and many villages they were much in evidence and their activities received extensive coverage in the local press. Their leaders, both clerical and lay, were often prominent figures in the local community as they sought to give expression to their Evangelical convictions tempered with a strong social conscience. From what they had to say about Congregational leadership, identity, doctrine and relations with the wider world and indeed their relative silence on the issue of gender relations, something of the essence of Edwardian Congregationalism emerges. In their discourses various tensions were to the fore, including those between faith and good works; the spiritual and secular impulses at the heart of the institutional principle; and the conflicting priorities of churches and society at large. -

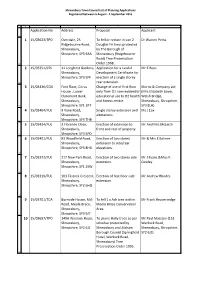

Application No Address Proposal Applicant 1 15/03623/TPO

Shrewsbury Town Council List of Planning Applications Registered between 5 August - 1 September 2015 A B C D E Application No Address Proposal Applicant 1 1 15/03623/TPO Overdale, 25 To fell or reduce in size 2 Dr Warren Perks Ridgebourne Road, Douglas Fir trees protected Shrewsbury, by The Borough of Shropshire, SY3 9AA Shrewsbury (Ridgebourne Road) Tree Preservation 472 Order 1968. 2 15/03351/CPL 11 Longhirst Gardens, Application for a Lawful Mr E Rees Shrewsbury, Development Certificate for Shropshire, SY3 5PF erection of a single storey 473 rear extension. 3 15/03436/COU First Floor, Cirrus Change of use of first floor Morris & Company Ltd House , Lower only from D1 non residential (Mrs Elizabeth Lowe, Claremont Bank, educational use to D2 health Welsh Bridge, Shrewsbury, and fitness centre. Shrewsbury, Shropshire, 474 Shropshire, SY1 1RT SY3 8LH) 4 15/03464/FUL 9 Vane Road, Single storey extension and Ms J Cox Shrewsbury, alterations. 475 Shropshire, SY3 7HB 5 15/03424/FUL 3 Florence Close, Erection of extension to Mr And Mrs McLeish Shrewsbury, front and rear of property. 476 Shropshire, SY3 5PD 6 15/03401/FUL 83 Woodfield Road, Erection of two storey Mr & Mrs E Balmer Shrewsbury, extension to side/rear Shropshire, SY3 8HU elevations. 477 7 15/03372/FUL 217 New Park Road, Erection of two storey side Mr J Evans &Miss K Shrewsbury, extension. Cowley Shropshire, SY1 2SW 478 8 15/03319/FUL 103 Tilstock Crescent, Erection of first floor side Mr Andrew Rhodes Shrewsbury, extension. Shropshire, SY2 6HQ 479 9 15/03701/TCA Burnside House, Mill To fell 1 x Ash tree within Mr Frank Heaversedge Road, Meole Brace, Meole Brace Conservation Shrewsbury, Area. -

The Parish of Durris

THE PARISH OF DURRIS Some Historical Sketches ROBIN JACKSON Acknowledgments I am particularly grateful for the generous financial support given by The Cowdray Trust and The Laitt Legacy that enabled the printing of this book. Writing this history would not have been possible without the very considerable assistance, advice and encouragement offered by a wide range of individuals and to them I extend my sincere gratitude. If there are any omissions, I apologise. Sir William Arbuthnott, WikiTree Diane Baptie, Scots Archives Search, Edinburgh Rev. Jean Boyd, Minister, Drumoak-Durris Church Gordon Casely, Herald Strategy Ltd Neville Cullingford, ROC Archives Margaret Davidson, Grampian Ancestry Norman Davidson, Huntly, Aberdeenshire Dr David Davies, Chair of Research Committee, Society for Nautical Research Stephen Deed, Librarian, Archive and Museum Service, Royal College of Physicians Stuart Donald, Archivist, Diocesan Archives, Aberdeen Dr Lydia Ferguson, Principal Librarian, Trinity College, Dublin Robert Harper, Durris, Kincardineshire Nancy Jackson, Drumoak, Aberdeenshire Katy Kavanagh, Archivist, Aberdeen City Council Lorna Kinnaird, Dunedin Links Genealogy, Edinburgh Moira Kite, Drumoak, Aberdeenshire David Langrish, National Archives, London Dr David Mitchell, Visiting Research Fellow, Institute of Historical Research, University of London Margaret Moles, Archivist, Wiltshire Council Marion McNeil, Drumoak, Aberdeenshire Effie Moneypenny, Stuart Yacht Research Group Gay Murton, Aberdeen and North East Scotland Family History Society, -

Shrewsbury Bus Stn - Sundorne - Harlescott

24 Shrewsbury Bus Stn - Sundorne - Harlescott Arriva Midlands Direction of stops: where shown (eg: W-bound) this is the compass direction towards which the bus is pointing when it stops Mondays to Fridays Shrewsbury, Bus Station (Stand H) 0815 then at these 15 35 55 1655 1715 1735 1805 1835 Sundorne, adj Our Lady of Pity Church 0829mins past 29 49 09until 1709 1729 1749 1819 1849 Harlescott, opp Tesco 0840each hour 40 00 20 1720 1740 1800 1830 1900 Saturdays Shrewsbury, Bus Station (Stand H) 0835 0905 0935 0955 1015 then at these 15 35 55 1555 1615 1635 1705 1735 1805 1835 Sundorne, adj Our Lady of Pity Church 0849 0919 0949 1009 1029mins past 29 49 09until 1609 1629 1649 1719 1749 1819 1849 Harlescott, opp Tesco 0900 0930 1000 1020 1040each hour 40 00 20 1620 1640 1700 1730 1800 1830 1900 Sundays no service 24 Harlescott - Sundorne - Shrewsbury Bus Stn Arriva Midlands Direction of stops: where shown (eg: W-bound) this is the compass direction towards which the bus is pointing when it stops Mondays to Fridays Harlescott, opp Tesco 0658 0728 0753 0813 then at these 13 33 53 1653 1713 Sundorne, opp Allerton Road Junction 0710 0740 0805 0825mins past 25 45 05until 1705 1725 Shrewsbury, Bus Station (Stand H) 0725 0755 0820 0840each hour 40 00 20 1720 1740 Saturdays Harlescott, opp Tesco 0748 0818 0848 0913 then at these 13 33 53 1553 1618 1648 1718 Sundorne, opp Allerton Road Junction 0800 0830 0900 0925mins past 25 45 05until 1605 1630 1700 1730 Shrewsbury, Bus Station (Stand H) 0815 0845 0915 0940each hour 40 00 20 1620 1645 1715 1745 Sundays no service 0 Shropshire Council20/09/2021 0654 24 Shrewsbury Bus Stn - Sundorne - Harlescott Arriva Midlands For times of the next departures from a particular stop you can use traveline-txt - by sending the SMS code to 84268.