View Technical Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proposed Solar Farm

BRYN HENLLYS EXTENSION PROPOSED SOLAR FARM ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT PREPARED BY PEGASUS GROUP | AUGUST 2019 P18-2622 | LIGHTSOURCE BP Pegasus Group Project Directory Statement of Competence The following competent experts have been involved in the preparation of this Environmental Statement on behalf of Lightsource BP. EIA Coordination Pegasus Group is a Member of the Institute of Environmental Management and Assessment (IEMA) and one of the founding members of the IEMA Quality Mark. Competent experts involved in the co- ordination of the Environmental Statement include Chartered members of the Royal Town Planning Institute and IEMA. Landscape and Visual Pegasus Group is a Registered Practice with the Landscape Institute. Our Landscape Architects regularly prepare Landscape and Visual Impact Assessments (LVIA) as part of EIA. The LVIA has been prepared by a Chartered Member of the Landscape Institute to ensure compliance with appropriate guidance. Cultural Heritage The Heritage team at Pegasus Group specialises in archaeology, built heritage and the historic landscape. The team holds individual memberships of the Royal Town Planning Institute (RTPI), the Institute of Historic Buildings Conservation (IHBC) and the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists (CIfA). The Archaeology and Cultural Heritage chapter was authored and reviewed by members of the CIfA. Biodiversity This chapter has been prepared and separately reviewed by Avian Ecology professional ecologists who are full members of the Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management (CIEEM) and are experienced in the field of ecological impact assessment. Transport & Access Competent experts involved in the assessment, preparation and checking of the Traffic and Transport chapter variously have Chartered membership of the Institute of Logistics & Transport (CMILT), Membership of the Chartered Institute of Highways & Transportation (MCIHT) or Membership of the Institution of Civil Engineers (MICE). -

BD22 Neath Port Talbot Unitary Development Plan

G White, Head of Planning, The Quays, Brunel Way, Baglan Energy Park, Neath, SA11 2GG. Foreword The Unitary Development Plan has been adopted following a lengthy and com- plex preparation. Its primary aims are delivering Sustainable Development and a better quality of life. Through its strategy and policies it will guide planning decisions across the County Borough area. Councillor David Lewis Cabinet Member with responsibility for the Unitary Development Plan. CONTENTS Page 1 PART 1 INTRODUCTION Introduction 1 Supporting Information 2 Supplementary Planning Guidance 2 Format of the Plan 3 The Community Plan and related Plans and Strategies 3 Description of the County Borough Area 5 Sustainability 6 The Regional and National Planning Context 8 2 THE VISION The Vision for Neath Port Talbot 11 The Vision for Individual Localities and Communities within 12 Neath Port Talbot Cwmgors 12 Ystalyfera 13 Pontardawe 13 Dulais Valley 14 Neath Valley 14 Neath 15 Upper Afan Valley 15 Lower Afan Valley 16 Port Talbot 16 3 THE STRATEGY Introduction 18 Settlement Strategy 18 Transport Strategy 19 Coastal Strategy 21 Rural Development Strategy 21 Welsh Language Strategy 21 Environment Strategy 21 4 OBJECTIVES The Objectives in terms of the individual Topic Chapters 23 Environment 23 Housing 24 Employment 25 Community and Social Impacts 26 Town Centres, Retail and Leisure 27 Transport 28 Recreation and Open Space 29 Infrastructure and Energy 29 Minerals 30 Waste 30 Resources 31 5 PART 1 POLICIES NUMBERS 1-29 32 6 SUSTAINABILITY APPRAISAL Sustainability -

Powys War Memorials Project Officer, Us Live with Its Long-Term Impacts

How to use this toolkit This toolkit helps local communities to record and research 4 Recording and looking after war memorials their First World War memorials. Condition of memorials Preparing a Conservation Maintenance Plan It includes information about the war, the different types of memorials Involving the community and how communities can record, research and care for their memorials. Grants It also includes case studies of five communities who have researched and produced fascinating materials about their memorials and the people they 5 Researching war memorials, the war and its stories commemorate. Finding out more about the people on the memorials The toolkit is divided into seven sections: Top tips for researching Useful websites 1 Commemorating the centenary of the First World War Places to find out more Tips from the experts 2 The First World War Regiments in Wales A truly global conflict Gathering local stories How did it all begin? A very short history of the war 6 What to do with the information Wales and the First World War A leaflet The men of Powys An interpretive panel Effects of war on communities and survivors An exhibition Why so many memorials? A First World War trail Memorials in Powys A poetry competition Poetry and musical events 3 War memorials What is a war memorial? 7 Case studies History of war memorials Brecon University of the Third Age Family History Group Types of war memorial Newtown Local History Group Symbolism of memorials Ystradgynlais Library Epitaphs The YEARGroup Materials used in war memorials L.L.A.N.I. Ltd Who is commemorated on memorials? How the names were recorded Just click on the tags below to move between the sections… 1 and were deeply affected by their experiences, sometimes for the rest Commemorating of their lives. -

Local Transport Fund 150,000 Bus Stop Infrastructure Enhancement

Schemes funded in 2019–2020 Details of the local transport grants awarded to each local authority are below: Blaenau Gwent Road Safety Revenue Grant 47,548 Education & Training Local Transport Fund 150,000 Bus Stop Infrastructure Enhancement Active Travel Fund Core Active Travel Fund Allocation 166,000 Bridgend Safe Routes in Communities Coity Higher Community Safe Routes 218,300 Newton Primary School 243,000 Road Safety Revenue Grant Education & Training 75,080 Local Transport Fund Penprysg Road Bridge, Pencoed 240,000 A4063 Sarn to Maesteg Highway enhancements 50,000 Bridgend to Coychurch Actiive Travel Route 750,000 Local Transport Network Fund Bus corridor enhancements 150,000 Active Travel Fund Strategic - Brackla to Bridgend Active Travel Route (INM-BR-44) 717,000 Local - Pencoed to Pencoed Technology Park 898,600 Core Active Travel Fund Allocation 316,000 Caerphilly Safe Routes in Communities Cycle Storage 31,000 Road Safety Revenue Grant Education & Training 88,500 Road Safety Capital Grant A4049/A469 Waunborfa Road Accident Remediation Scheme 20,000 1 Mass action/area wide – Accident Remediation Project – Vehicle 64,000 Activated Signs Local Transport Fund Bus Stop Enhancements – Caerphilly Basin 131,000 Bus Stop Enhancements – Mid Valley Area 150,000 Active Travel Fund Strategic - Phase One - Ystrad Mynach to Pengam 177,000 Core Active Travel Fund Allocation 390,000 Cardiff Safe Routes in Communities Ninian Park Primary 267,411 Road Safety Revenue Grant Education & Training 183,675 Road Safety Capital Grant Crwys Road – traffic -

Wind Powered Electricity in the UK Wind Powered Electricity in the UK

Special feature – Wind powered electricity in the UK Wind powered electricity in the UK This article looks at wind powered electricity in the UK, examining how its position in the UK energy mix has shifted from 2010 to 20191, and how wind capacity may change in the future. Key points • Total wind generating capacity increased by 19 GW from 5.4 GW in 2010 to 24 GW in 2019. This is the result of sizeable increases in capacity both onshore and offshore, which are up 10 GW and 8.5 GW respectively. • In the last year, UK offshore wind capacity rose 1.6 GW following the opening of Hornsea One, Beatrice extension (partially operational in 2018) and East Anglia One (partially operational). Hornsea One is now the largest offshore wind farm in the world with an operational capacity of over 1.2 GW. • In 2019, wind generators became the UK’s second largest source of electricity, providing 64 TWh; almost one fifth of the UK’s total generation. This was achieved by record onshore and offshore generation despite suboptimal conditions for wind, with 2019 reporting the lowest average wind speeds since 2012. • Onshore generation exceeded offshore for every year 2010 to 2019, however the gap narrowed each year. In 2019 the difference was marginal with each providing 32 TWh of electricity and 9.9 per cent of the UK’s total generation. • Offshore sites are typically able to use more of their available capacity for generation, as wind speed and direction are more consistent offshore. This is measured by the load factor, the proportion of maximum generation achieved. -

Envt1635-Lp-Ldp Reg of Alt Sites

Neath Port Talbot County Borough Council Local Development Plan 2011 –2026 Register of Alternative Sites January 2014 www.npt.gov.uk/ldp Contents 1 Register of Alternative Sites 1 2014) 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 What is an Alternative Site? 1 (January 1.3 The Consultation 1 Sites 1.4 Register of Alternative Sites 3 1.5 Consequential Amendments to the LDP 3 Alternative of 1.6 What Happens Next? 4 1.7 Further Information 4 Register - LDP APPENDICES Deposit A Register of Alternative Sites 5 B Site Maps 15 PART A: New Sites 15 Afan Valley 15 Amman Valley 19 Dulais Valley 21 Neath 28 Neath Valley 37 Pontardawe 42 Port Talbot 50 Swansea Valley 68 PART B: Deleted Sites 76 Neath 76 Neath Valley 84 Pontardawe 85 Port Talbot 91 Swansea Valley 101 PART C: Amended Sites 102 Neath 102 Contents Deposit Neath Valley 106 Pontardawe 108 LDP Port Talbot 111 - Register Swansea Valley 120 of PART D: Amended Settlement Limits 121 Alternative Afan Valley 121 Amman Valley 132 Sites Dulais Valley 136 (January Neath 139 2014) Neath Valley 146 Pontardawe 157 Port Talbot 159 Swansea Valley 173 1 . Register of Alternative Sites 1 Register of Alternative Sites 2014) 1.1 Introduction 1.1.1 The Neath Port Talbot County Borough Council Deposit Local Development (January Plan (LDP) was made available for public consultation from 28th August to 15th October Sites 2013. Responses to the Deposit consultation included a number that related to site allocations shown in the LDP. Alternative 1.1.2 In accordance with the requirements of the Town and Country Planning (Local of Development Plan) (Wales) Regulations 2005(1), the Council must now advertise and consult on any site allocation representation (or Alternative Sites) received as soon as Register reasonably practicable following the close of the Deposit consultation period. -

UK Innovation Systems for New and Renewable Energy Technologies

The UK Innovation Systems for New and Renewable Energy Technologies Final Report A report to the DTI Renewable Energy Development & Deployment Team June 2003 Imperial College London Centre for Energy Policy and Technology & E4tech Consulting ii Executive summary Background and approach This report considers how innovation systems in the UK work for a range of new and renewable energy technologies. It uses a broad definition of 'innovation' - to include all the stages and activities required to exploit new ideas, develop new and improved products, and deliver them to end users. The study assesses the diversity of influences that affect innovation, and the extent to which they support or inhibit the development and commercialisation of innovative new technologies in the UK. The innovation process for six new and renewable energy sectors is analysed: • Wind (onshore and offshore) • Marine (wave and tidal stream) • Solar PV • Biomass • Hydrogen from renewables • District and micro-CHP In order to understand innovation better, the report takes a systems approach, and a generic model of the innovation system is developed and used to explore each case. The systems approach has its origins in the international literature on innovation. The organising principles are twofold: • The stages of innovation. Innovation proceeds through a series of stages, from basic R&D to commercialisation – but these are interlinked, and there is no necessity for all innovations to go through each and every stage. The stages are defined as follows: Basic and applied R&D includes both ‘blue skies’ science and engineering/application focused research respectively; Demonstration from prototypes to the point where full scale working devices are installed in small numbers; Pre-commercial captures the move from the first few multiples of units to much larger scale installation for the first time; Supported commercial is the stage where technologies are rolled out in large numbers, given generic support measures; Commercial technologies can compete unsupported within the broad regulatory framework. -

Weekly List of New Planning Applications. Week Ending 1 Sep 2020

Weekly list of new planning applications. Week ending 1 Sep 2020 Application No. P2020/0693 Officer Andrea Davies Type Full Plans Ward Pontardawe Date Valid 21st August 2020 Parish Pontardawe Town Council Proposal Change of use of shop to residential accommodation in association with existing dwelling, removal of shop front and construction of front extension. Location 73 High Street Pontardawe Swansea Neath Port Talbot SA8 4JN Applicant’s Name & Address Agent’s Name & Address TFMG Holdings 001 Limited Mr John Davies 12 High Street JD Architectural Services Pontardawe 61 Gwyrddgoed Road Swansea Pontardawe SA8 4HU Swansea United Kingdom SA8 4NL United Kingdom Easting 272364 Northing 204275 ********************************************************************************** Application No. P2020/0705 Officer Helen Bowen Type Discharge of Conditions Ward Onllwyn Date Valid 26th August 2020 Parish Onllwyn Community Council Proposal Details to be agreed in association with Condition 3 (car parking scheme) of P2020/0375 granted on 6/7/20 Location Ty Caris Roman Road Banwen Neath SA10 9LH Applicant’s Name & Address Dr Elizabeth Hill O'Shea Ty Caris Roman Road Banwen Neath SA10 9LH Easting 285605 Northing 209628 ********************************************************************************** Page 1 of 9 Application No. P2020/0708 Officer Matt Fury Type Proposed Lawful Ward Margam Development Certificate Date Valid 24th August 2020 Parish Port Talbot Proposal Single storey side and rear extension. (Lawful Development Certificate Proposed) Location -

Adroddiad Blynyddol 1979

ADRODDIAD BLYNYDDOL / ANNUAL REPORT 1978-79 J D K LLOYD 1979001 Ffynhonnell / Source The late Mr J D K Lloyd, O.B.E., D.L., M.A., LL.D., F.S.A., Garthmyl, Powys. Blwyddyn / Year Adroddiad Blynyddol / Annual Report 1978-79 Disgrifiad / Description Two deed boxes containing papers of the late Dr. J. D. K. Lloyd (1900-78), antiquary, author of A Guide to Montgomery and of various articles on local history, formerly mayor of Montgomery and high sheriff of Montgomeryshire, and holder of several public and academic offices [see Who's Who 1978 for details]. The one box, labelled `Materials for a History of Montgomery', contains manuscript volumes comprising a copy of the glossary of the obsolete words and difficult passages contained in the charters and laws of Montgomery Borough by William Illingworth, n.d. [watermark 1820), a volume of oaths of office required to be taken by officials of Montgomery Borough, n.d., [watermark 1823], an account book of the trustees of the poor of Montgomery in respect of land called the Poors Land, 1873-96 (with map), and two volumes of notes, one containing notes on the bailiffs of Montgomery for Dr. Lloyd's article in The Montgomeryshire Collections, Vol. 44, 1936, and the other containing items of Montgomery interest extracted from Archaeologia Cambrensis and The Montgomeryshire Collections; printed material including An Authentic Statement of a Transaction alluded to by James Bland Burgess, Esq., in his late Address to the Country Gentlemen of England and Wales, 1791, relating to the regulation of the practice of county courts, Letters to John Probert, Esq., one of the devisees of the late Earl of Powis upon the Advantages and Defects of the Montgomery and Pool House of Industry, 1801, A State of Facts as pledged by Mr. -

Tai Tarian – Playing Their Part in a Sustainable Future in 2018, Tai Tarian Joined Wales’ Bee Friendly They Helped Them to Design and Create Bug Initiative

Case Studies Tai Tarian – playing their part in a sustainable future In 2018, Tai Tarian joined Wales’ Bee Friendly They helped them to design and create bug initiative. Tai Tarian is one of the largest hotels, which are located at Baglan. social housing providers in Wales, owning over 9000 properties and managing over Tai Tarian has worked with Buglife Cymru to 450 acres in the Neath Port Talbot County. create wildflower and community woodlands In 2016, with a member of staff fully trained habitats for pollinators along identified to become their resident beekeeper, they ‘B-lines’ (www.buglife.org.uk). They feel installed bee hives at their head office in that the key to success in their projects is Baglan. Following this, they made links with the connections they have made with local local school children and educated them on schools and communities. the importance of bees. Partnership working has given pride and Apprentices employed on their Copper value to the projects, which have enhanced Foundation programme worked with the green spaces and improved biodiversity in children. the Borough. Enhancing our Haven Housing Schemes (independent living for the over 55’s) Initially, Haven Housing tenants were invited to coffee mornings. During these, Clare Dinham (Buglife Cymru) explained the B-Line project and the work required for wildflower planting. The Tai Tarian team encouraged tenants to get involved in whatever way they felt comfortable. This could be helping to prepare ground or sowing seeds. If mobility were an issue, tenants could promote the B-Line projects to friends and families. At several housing schemes, tenants have seen and enjoyed the benefits of wildflower meadows in full bloom. -

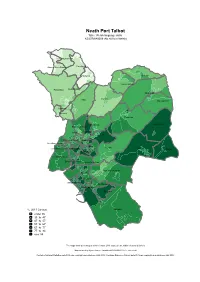

Neath Port Talbot Table: Welsh Language Skills KS207WA0009 (No Skills in Welsh)

Neath Port Talbot Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0009 (No skills in Welsh) Lower Brynamman Cwmllynfell Gwaun−Cae−Gurwen Ystalyfera Onllwyn Seven Sisters Pontardawe Godre'r graig Glynneath Rhos Crynant Blaengwrach Trebanos Allt−wen Resolven Aberdulais Glyncorrwg Bryn−coch North Dyffryn Cadoxton Tonna Bryn−coch South Neath North Coedffranc North Cimla Pelenna Cymmer Coedffranc Central Neath East Gwynfi Neath South Coedffranc West Briton Ferry West Briton Ferry East Bryn and Cwmavon Baglan Aberavon Sandfields West Port Talbot Sandfields East Tai−bach %, 2011 Census Margam under 35 35 to 47 47 to 57 57 to 67 67 to 77 77 to 84 over 84 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 output areas, within electoral divisions Map created by Hywel Jones. Variables KS208WA0022−27 corrected Contains National Statistics data © Crown copyright and database right 2013; Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Neath Port Talbot Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0010 (Can understand spoken Welsh only) Lower Brynamman Gwaun−Cae−Gurwen Cwmllynfell Onllwyn Ystalyfera Seven Sisters Pontardawe Godre'r graig Glynneath Rhos Crynant Blaengwrach Allt−wen Trebanos Resolven Aberdulais Bryn−coch North Glyncorrwg Dyffryn Cadoxton Tonna Coedffranc North Bryn−coch South Neath North Coedffranc Central Neath South Pelenna Gwynfi Cimla Cymmer Neath East Briton Ferry West Coedffranc West Briton Ferry East Bryn and Cwmavon Baglan Sandfields West Aberavon Port Talbot Sandfields East Tai−bach %, 2011 Census Margam under 4 4 to 5 5 to 7 7 to 9 9 to 12 12 to 14 over 14 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 output areas, within electoral divisions Map created by Hywel Jones. -

Key Data Amman Valley, Spring 2009

Key data Amman Valley, Spring 2009 Contents 1 Introduction 3 2009 2 Population and Social Profile 5 Spring 2.1 Population 5 , alley 2.2 Ethnicity 5 V 2.3 Welsh Language 5 Amman 2.4 Health 5 data 2.5 Housing 5 Key 2.6 The Economy and Employment 6 2.7 Communities First Areas 6 2.8 Welsh Index of multiple deprivation 6 3 Access to facilities 9 3.1 Facilities and services 9 3.2 Highways and Access to a private car 11 3.3 Travel to work 11 3.4 Public transport 11 4 Minerals, Renewables and Waste 13 4.1 Mineral and aggregate resources 13 4.2 Renewable Energy 13 4.3 Waste 13 5 Quality of Life 15 5.1 Air Quality and Noise Pollution 15 5.2 SSSIs and areas of nature conservation 15 5.3 Built Heritage 15 Contents Key data Amman Valley, Spring 2009 1 . Introduction 1 Introduction 2009 This is one of a series of overview papers that are being prepared to inform discussion Spring on the preparation of the plan. These overview papers outline the main issues that have , been identified through work on the background papers. They will be amended and alley expanded as the discussion and work develops and any comments on omissions or V corrections will be gratefully received. Amman Background papers are being prepared on the 8 community areas that make up Neath Port Talbot and on specific themes such as housing. They will be available from the LDP data website www.npt.gov.uk/ldp Key How to contact the LDP team 1.