Debating the Connotations of the Concept of Vyakti-Jati- Akrti: an Epistemological Overview in the Context of Bhedabheda Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What the Upanisads Teach

What the Upanisads Teach by Suhotra Swami Part One The Muktikopanisad lists the names of 108 Upanisads (see Cd Adi 7. 108p). Of these, Srila Prabhupada states that 11 are considered to be the topmost: Isa, Kena, Katha, Prasna, Mundaka, Mandukya, Taittiriya, Aitareya, Chandogya, Brhadaranyaka and Svetasvatara . For the first 10 of these 11, Sankaracarya and Madhvacarya wrote commentaries. Besides these commentaries, in their bhasyas on Vedanta-sutra they have cited passages from Svetasvatara Upanisad , as well as Subala, Kausitaki and Mahanarayana Upanisads. Ramanujacarya commented on the important passages of 9 of the first 10 Upanisads. Because the first 10 received special attention from the 3 great bhasyakaras , they are called Dasopanisad . Along with the 11 listed as topmost by Srila Prabhupada, 3 which Sankara and Madhva quoted in their sutra-bhasyas -- Subala, Kausitaki and Mahanarayana Upanisads --are considered more important than the remaining 97 Upanisads. That is because these 14 Upanisads are directly referred to by Srila Vyasadeva himself in Vedanta-sutra . Thus the 14 Upanisads of Vedanta are: Isa, Kena, Katha, Prasna, Mundaka, Mandukya, Aitareya, Taittiriya, Brhadaranyaka, Chandogya, Svetasvatara, Kausitaki, Subala and Mahanarayana. These 14 belong to various portions of the 4 Vedas-- Rg, Yajus, Sama and Atharva. Of the 14, 8 ( Brhadaranyaka, Chandogya, Taittrirya, Mundaka, Katha, Aitareya, Prasna and Svetasvatara ) are employed by Vyasa in sutras that are considered especially important. In the Gaudiya Vaisnava sampradaya , Srila Baladeva Vidyabhusana shines as an acarya of vedanta-darsana. Other great Gaudiya acaryas were not met with the need to demonstrate the link between Mahaprabhu's siksa and the Upanisads and Vedanta-sutra. -

Historical Continuity and Colonial Disruption

8 Historical Continuity and Colonial Disruption major cause of the distortions discussed in the foregoing chapters A has been the lack of adequate study of early texts and pre-colonial Indian thinkers. Such a study would show that there has been a historical continuity of thought along with vibrant debate, controversy and innovation. A recent book by Jonardan Ganeri, the Lost Age of Reason: Philosophy in Early Modern India 1450-1700, shows this vibrant flow of Indian thought prior to colonial times, and demonstrates India’s own variety of modernity, which included the use of logic and reasoning. Ganeri draws on historical sources to show the contentious nature of Indian discourse. He argues that it did not freeze or reify, and that such discourse was established well before colonialism. This chapter will show the following: • There has been a notion of integral unity deeply ingrained in the various Indian texts from the earliest times, even when they 153 154 Indra’s Net offer diverse perspectives. Indian thought prior to colonialism exhibited both continuity and change. A consolidation into what we now call ‘Hinduism’ took place prior to colonialism. • Colonial Indology was driven by Europe’s internal quest to digest Sanskrit and its texts into European history without contradicting Christian monotheism. Indologists thus selectively appropriated whatever Indian ideas fitted into their own narratives and rejected what did not. This intervention disrupted the historical continuity of Indian thought and positioned Indologists as the ‘pioneers’. • Postmodernist thought in many ways continues this digestion and disruption even though its stated purpose is exactly the opposite. -

La Bhagavad-Gita “Telle Qu’Elle Est”

LA BHAGAVAD-GITA “TELLE QU’ELLE EST” Sa Divine Grâce A.C Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. PREFACE Le public français a surtout entendu parler jusqu'ici de la voie du yoga et de la voie du jnana (connais- sance libératrice) comme représentatives des doctrines et méthodes spirituelles de l'Inde brah- manique. Or voici que depuis quelque temps son attention est attirée, de diverses manières, sur la voie de la bhakti, par les adeptes de la "Conscience de Krsna". C'est un fait: l'intelligentsia hindoue moderne et, à sa suite, cette partie de l'opinion occidentale qu'a marquée le néo-hindouisme, n'ont pas rendu pleine justice au chemin de la bhakti, tenu pour populaire et mineur, ou, au mieux, subordonné. Il faut assurément faire appel de ce jugement. La tradition bhakta a suscité l'un des monuments les plus grandioses —en ampleur et en valeur— de l'indianité. Certaines de ses manifestations peuvent apparaître déconcertantes, surtout lorsqu'elles se présentent hors du cadre indien. Mais il convient de voir au-delà. Qu'est-ce donc que la bhakti? Le terme se rattache à une racine verbale sanskrite —bhaj— signifiant, à l'actif: donner en partage, et, au moyen: recevoir en partage. D'où le substantif: bhaga, la bonne part, le bonheur, à partir duquel a été formé l'un des Noms divins: Bhaga-van, Celui qui a la bonne part, le Bienheureux. L'adjectif verbal bhakta, entre autres acceptions, s'applique aux personnes qui reçoivent par grâce une part de la vie divine, s'engagent totalement en la cause du Bienheureux, se dévouent sans réserve à Son service. -

The Vedanta-Kaustubha-Prabha of Kesavakasmtribhajta : a Critical Study

THE VEDANTA-KAUSTUBHA-PRABHA OF KESAVAKASMTRIBHAJTA : A CRITICAL STUDY THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF D. LITT. TO ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY. ALIGARH 1987 BY DR. MAOAN MOHAN AGRAWAL M.A., Ph. D. Reader in Sanskrit, University of Delhi T4201 T420 1 THE VEDANTA-KAUSTUBHA-PRAT^HA OF KESAVAKASMIRIBHATTA : * • A CRITICAL STUDY _P _F^_E_F_A_C_E_ IVie Nimbarka school of Vedanta has not so far been fully explored by modern scholars. There are only a couple of significant studies on Nimbarka, published about 50 years ago. The main reason for not ransacking this system seems to be the non availability of the basic texts. The followers of this school did not give much importance to the publications and mostly remained absorbed in the sastric analysis of the Ultimate Reality and its realization. One question still remains unanswered as to why there is no reference to Sankarabhasya in Nimbarka's commentary on the Brahma-sutras entitled '"IVie Vedanta-pari jata-saurabha", and why Nimbarka has not refuted the views of his opponents, as the other Vaisnava Acaryas such as R"amanuja, Vallabha, ^rikara, Srikantha and Baladeva Vidyabhusana have done. A comprehensive study of the Nimbarka school of Vedanta is still a longlelt desideratum. Even today the basic texts of this school are not available to scholars and whatsoever are available, they are in corrupt form and the editions are full of mistakes. (ii) On account of the lack of academic interest on the part of the followers of this school, no critical edition of any Sanskrit text has so far been prepared. Therefore, the critical editions of some of the important Sanskrit texts viz. -

Read Book Ideas of Human Nature from the Bhagavad Gita To

IDEAS OF HUMAN NATURE FROM THE BHAGAVAD GITA TO SOCIOBIOLOGY 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK David P Barash | 9780136475873 | | | | | Ideas of Human Nature From the Bhagavad Gita to Sociobiology 1st edition PDF Book Disobedience: Concept and Practice. Chapter 11 of the Gita refers to Krishna as Vishvarupa above. Krishna reminds him that everyone is in the cycle of rebirths, and while Arjuna does not remember his previous births, he does. Nadkarni and Zelliot present the opposite view, citing early Bhakti saints of the Krishna-tradition such as the 13th-century Dnyaneshwar. Sartre: Existentialism and Humanism and Being and Nothingness. Bhagavad-gita As It Is. Lucretius: On the Nature of Things. Bhakti is the most important means of attaining liberation. Very Good dust jacket. About this Item: Wisdom Tree. We're sorry! More information about this seller Contact this seller Javascript is not enabled in your browser. Yet he is a historical figure also. View basket. Samsung now 5th in 'Best Global Brands ' list, Apple leads. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Volume 1. Swami Vivekananda , the 19th-century Hindu monk and Vedantist, stated that the Bhagavad Gita may be old but it was mostly unknown in the Indian history till early 8th century when Adi Shankara Shankaracharya made it famous by writing his much-followed commentary on it. Sampatkumaran, a Bhagavad Gita scholar, the Gita message is that mere knowledge of the scriptures cannot lead to final release, but "devotion, meditation, and worship are essential. This is evidenced by the discontinuous intermixing of philosophical verses with theistic or passionately theistic verses, according to Basham. -

Bhagavata Precepts Book.Indb

THE BHAGAVATA ITS PHILOSOPHY, ITS ETHICS, AND ITS THEOLOGY & LIFE AND PRECEPTS OF SRI CHAITANYA MAHAPRABHU By Srila Saccidananda Bhaktivinoda Thakura THE BHAGAVATA ITS PHILOSOPHY, ITS ETHICS, AND ITS THEOLOGY & LIFE AND PRECEPTS OF SRI CHAITANYA MAHAPRABHU By Srila Saccidananda Bhaktivinoda Thakura THE BHAGAVATA ITS PHILOSOPHY, ITS ETHICS, AND ITS THEOLOGY By Sri Srila Thakur Bhaktivinode “O Ye, who are deeply merged in the knowledge of the love of God and also in deep thought about it, constantly drink, even after your emancipation, the most tasteful juice of the Srimad-Bhagavatam, come on earth through Sri Sukadeva Gosvami’s mouth carrying the liquid nectar out of the fallen and, as such, very ripe fruit of the Vedic tree which supplies all with their desired objects.” (Srimad-Bhagavatam, 1/1/3) THE BHAGAVATA ITS PHILOSOPHY, ITS ETHICS, AND ITS THEOLOGY We love to read a book which we never read before. We are anxious to gather whatever information is contained in it and with such acquirement our curiosity stops. This mode of study prevails amongst a great number of readers, who are great men in their own estimation as well as in the estimation of those, who are of their own stamp. In fact, most readers are mere repositories of facts and statements made by other people. But this is not study. The student is to read the facts with a view to create, and not with the object of fruitless retention. Students like satellites should reflect whatever light they receive from authors and not imprison the facts and thoughts just as the Magistrates imprison the convicts in the jail! Thought is progressive. -

Modern Indian Responses to Religious Pluralism Author: Coward, Harold G

cover cover next page > title: Modern Indian Responses to Religious Pluralism author: Coward, Harold G. publisher: State University of New York Press isbn10 | asin: 0887065724 print isbn13: 9780887065729 ebook isbn13: 9780585089959 language: English subject Religious pluralism--India, Religious pluralism-- Hinduism. publication date: 1987 lcc: BL2015.R44M63 1987eb ddc: 291.1/72/0954 subject: Religious pluralism--India, Religious pluralism-- Hinduism. cover next page > If you like this book, buy it! file:///C:/...,%20Harold%20G.%20-%20Modern%20Indian%20Responses%20to%20Religious%20Pluralism/files/cover.html[26.08.2009 16:19:34] cover-0 < previous page cover-0 next page > Modern Indian Responses to Religious Pluralism Edited by Harold G. Coward State University of New York Press < previous page cover-0 next page > If you like this book, buy it! file:///C:/...20Harold%20G.%20-%20Modern%20Indian%20Responses%20to%20Religious%20Pluralism/files/cover-0.html[26.08.2009 16:19:36] cover-1 < previous page cover-1 next page > Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 1987 State University of New York Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address State University of New York Press, State University Plaza, Albany, N.Y., 12246 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Modern Indian responses to religious pluralism. Includes bibliographies -

1 Unit 3 Prominent Theistic Philosophers of India

UNIT 3 PROMINENT THEISTIC PHILOSOPHERS OF INDIA Contents 3.0 Objectives 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Sankara (788-820) 3.3 Ramanuja (1017-1137) 3.4 Madhva (1238-1317) 3.5 Nimbarka (1130-1200) 3.6 Aurobindo (1872-1950) 3.7 Ramakrishna Paramahamsa (1836-1886) 3.8 Ramana Maharshi (1879-1950) 3.9 Let Us Sum Up 3.10 Key Words 3.11 Further Readings and References 3.0 OBJECTIVES The objective of this unit is to make the students acquainted with the background, origin and development of Indian Theism. The discussion will bring out the philosophical significance of Indian theism by highlighting a few prominent Indian theistic philosophers. 3.1 INTRODUCTION Theism as understood commonly is a philosophically reasoned understanding of reality that affirms that the source and continuing ground of all things is in God; that the meaning and fulfillment of all things lie in their relation to God; and that God intends to realize the meaning and fulfillment. Theism is, literally, belief in the existence of God. Though the concept is as old as philosophy, the term itself appears to be of relatively recent origin. Some have suggested that it appeared in the seventeenth century in England. At the end one could say that the term is used to denote certain philosophical or theological positions, regardless of whether this involves a religious relationship to the God of whom individuals speak. Let us discuss the basic philosophies of the theistic philosophers of India from ancient period to contemporary period following one or the other above schools of philosophical tradition. -

SEVĀ in HINDU BHAKTI TRADITIONS by VED RAVI PATEL a THESIS PRESENTED to the GRADUATE SCHOOL of the UN

ENGAGING IN THE WORLD: SEVĀ IN HINDU BHAKTI TRADITIONS By VED RAVI PATEL A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2012 1 © 2012 Ved Ravi Patel 2 To Anu, Rachu, Bhavu, Milio, Maho, and Sony, for keeping things light 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank a number of people for the support they have given me. First, I would like to thank both of my esteemed committee members, Professor Vasudha Narayanan and Professor Whitney Sanford, for helping me put together a project that I once feared would never come together. I would also like to thank my colleagues Jaya Reddy, James “Jimi” Wilson, and Caleb Simmons for constantly giving me advice in regards to this thesis and otherwise. Finally, I would like to extend my warmest gratitude to those who took care of me for the last two years while I was away from my family and home in California. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................... 7 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 9 Setting the Stage ...................................................................................................... 9 The Question of Terminology ................................................................................. -

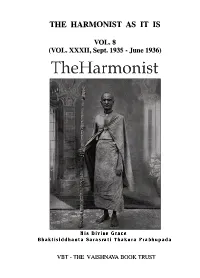

The Harmonist As It Is No 8

THE HARMONIST AS IT IS VOL.8 (VOL. XXXII, Sept. 1935 - June 1936) VBT - THE V AISHNAVA BOOK TRUST PREFACE If we speak of God as the Supreme, Who is above absolutely everyone and everything known and unknown to us, we must agree that there can be only one God. Therefore God, or the Absolute Truth, is the common and main link of the whole creation. Nonetheless, and although God is One, we must also agree that being the Supreme, God can also manifest as many, or in the way, shape and form that may be most pleasant or unpleasant. In other words, any sincere student of a truly scientific path of knowledge about God, must leam that the Absolute Truth is everything and much above anything that such student may have ever known or imagined. Therefore, a true conclusion of advanced knowledge of God must be that not only is God one, but also that God manifests as many. Only under this knowledge and conclusion, a perspective student of the Absolute Truth could then understand the deep purport behind polytheism. since the existence of various 'gods' cannot be other than different manifestations from the exclusive source, which is the same and only Supreme God. Nonetheless, the most particular path of knowledge that explain in detail all such manifestations or incarnations, in a most convincing and authoritative description, can be found in the vast Vedas and Vaishnava literature. The revealed scriptures of mankind have several purposes. All bona fide sacred texts declare that God will be always besides His devotees and somehow will chastise His enemies or miscreants. -

Sri Ramakrishna the New Man of The

Sri Ramakrishna: The ‘New Man’ of the Age by Swami Bhajanananda (The author is Assistant-Secretary, Ramakrishna Math and Ramakrishna Mission.) Published in Prabuddha Bharata January 2011 thru May 2012 Table of Contents SECTION I....................................................................................................... 3 PB January 2011............................................................................................... 3 The Epochs.............................................................................................. 3 Paradigm Shifts.........................................................................................4 The Power of Ideas....................................................................................5 Swamiji’s Concept of Epochal Ideas.................................................................6 Role of the Prophet....................................................................................7 The Epochal ‘New Man’...............................................................................8 PB February 2011............................................................................................12 Significance of Sri Ramakrishna’s Avatarahood...................................................12 Avatara as Kapāla-mocana..........................................................................12 The Avatara as the Door to the Infinite...........................................................13 The Avatara as the Revelation of the Noumenon................................................14 -

1 Unit 1 VEDANTA

Unit 1 VEDANTA: AN INTRODUCTION CONTENTS 1.1 Objectives 1.2 Introduction 1.3 Vedanta Sutras 1.4 Major schools of Vedanta 1.5 Sankara and Advaitavada 1.6 Ramanuja and Visistadvaita 1.7 Madhva (1199 – 1278 A.D) and Dvaita Vedanta 1.8 Vallabha (1473-1531) and Suddhadvaita 1.9 Nimbarka and Svabhavika Bhedabheda 1.10 Key words 1.11 Further Readings and References 1.12 Answers to check your progress 1.1 OBJECTIVES Vedanta Philosophy deserves great attention today for many reasons: in the first place for its philosophical value and secondly and more importantly because it is closely bound up with the religion of India and is much more alive in the Indian subcontinent than any other system of thought. Vedanta determines, in one or the other of its forms, the world view of the Hindu thinkers of the present time. The Unit apparently has two parts: • The first part intends to make the students familiar with a general study of Vedanta focussing mainly on its meaning, philosophical background and teachings. • The second part, in turn, will take up the major Vedanta Philosophers who have immensely contributed to the development of the various schools within Vedanta system. • Such a study, though brief, will help the students to identity those streams of thought that have continued to have impact on the later thought in India, particularly during the neo- Vedantic times. 1.2 INTRODUCTION The literal meaning of the term Vedanta is “the end of the Vedas, the concluding parts of the Vedas, the culmination of the Vedic teaching and wisdom”.